A friend gave me a clip-on-a-stand that you could use to display a postcard. Into it I slipped the photo I’d taken of the tree with the canoe-shaped scar in its bark. It sat next to the piece of roof tile from the Thames.

I’d come back from Wiseman’s Ferry after that day with Patrick full of a kind of calm energy. I knew what to do now, which was, in a manner of speaking, to do nothing.

First, do no harm. Wasn’t that what doctors promised when they took the Hippocratic Oath? The way to do no harm to these pages was to do them the courtesy of listening to them.

I read the whole lot straight through, without making notes or trying to analyse. At the end of that reading, I decided not to make any more grand plans for the book. No more lists, no more attempts to see the shape of the whole thing. I’d start by making simple categories, and see where that led. I started with the biggest, simplest kind of rearrangement. I made two folders: ‘London’ and ‘Australia’. Then I put the contents of each folder in what I thought might be chronological order.

The London material fell naturally into this structure.

Solomon Wiseman is born in the slums of Bermondsey. His childhood sweetheart, Sophia, is the daughter of a light-erman who takes Wiseman on as his apprentice. Solomon plans to marry Sophia as soon as his apprenticeship is over.

But his friend William Warner persuades him to go to the notorious Cherry Gardens with him and a couple of good-looking girls. Wiseman is swept up by one of them, Jane. She falls pregnant and Wiseman is forced to marry her.

Soon after, Warner marries Sophia—cynically, in hopes of inheriting her father’s business. He is violent towards her, even breaks her jaw. Wiseman discovers this and gives Warner a savage beating.

Wiseman has always stolen from the loads he’s carried. One night his employer—tipped off in advance by Warner, in revenge for the beating—catches him stealing some timber. He is tried and condemned to death, then to transportation for life. Jane is given permission to accompany him, and in 1806 they set sail for New South Wales.

I printed this out—a satisfying pile of about 80 pages—and put it away.

The folder called ‘Australia’ held about 140 pages. I did my best to put them into chronological order, too.

The Wisemans arrive in Sydney, Solomon gets a pardon, buys a boat, starts trading up and down the Hawkesbury. Against Jane’s wishes they settle there.

There are various encounters with the Darug—some friendly, some hostile.

Wiseman plots a long-distance revenge on Warner. Through his brother, he arranges for Warner to be caught stealing. When Warner is transported, Solomon makes sure that his old rival is assigned to him. Unexpectedly, Sophia is also with him and the two couples live uncomfortably together for a time as masters and servants. Wiseman and Sophia resume their love affair in secret. But Jane humiliates and mistreats Sophia, so Wiseman arranges for Sophia and Warner to set up on land nearby.

Jane and Solomon argue continually about the ‘blacks’— Jane is frightened of them and wants to go back to London. During one of their arguments he hits her and she falls down the stairs and is killed. Wiseman more or less buys Sophia from Warner and establishes her as his housekeeper. In due course Warner dies and Wiseman and Sophia marry. There are a few more meetings between settlers and Darug. As before, some are friendly, some are hostile.

After escalating attacks on both sides, a posse of settlers is organised. It combines with troops to form a Black Line to round up all the local Darug. The Black Line is a failure but later there’s a massacre in which most of the Darug are killed. Then there’s the bit about the fig tree and the rock.

I was pleased with this. None of my previous novels had much plot. That was all right—some of my favourite books had no plots to speak of. But I was proud of the fact that, with the story of Wiseman getting his revenge on Warner, I’d stumbled on a plot of almost operatic complexity. All it needed was a few cases of mistaken identity and a bit of cross-dressing.

Dividing things up seemed to be working, so I split the ‘Australia’ folder into two: one called ‘White story’ and one called ‘Aboriginal story’.

With the meetings with Aboriginal people removed, ‘White story’ flowed much more smoothly.

‘Aboriginal story’ was more difficult. I found the same problem that Sturt did with those different tribes on the Murray. Sometimes the Aboriginal people were friendly to the Wisemans and sometimes they weren’t, and I didn’t understand why.

Still, I tried to make some kind of sequence. The scene based on that event with Governor Phillip, where an old man shows Wiseman a nice cosy cave to stay out of the rain: that went at the beginning, when things were friendly. The scene where the Aboriginal people burn an area of ground near the Wisemans’ hut: it felt like a threat, so it went in the middle when things were becoming tense. The scene where a settler gets a spear through the stomach: that went at the end.

The two stories could be made to go smoothly on their own, but I couldn’t find a way to knit them together. They bucked against each other like some clever bit of postmodernism.

It seemed to be a question of sequence. Should Wiseman discover that William Warner dobbed him in before or after he settles on the Hawkesbury? Should Jane die, and Wiseman marry Sophia Warner, before or after the Darug start the fire?

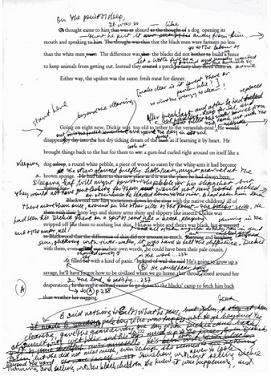

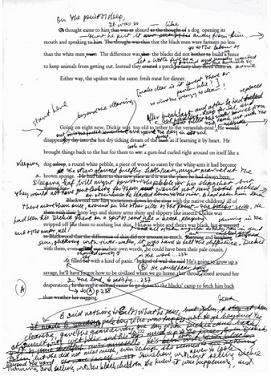

I made lists, I made lists in columns, I made summaries of each scene and wrote them on sticky notes that I rearranged on the window above the desk. I tried cutting the book into chapters, and gave each chapter a title. In desperation I got out my big scissors and cut the printout into sections. I was hoping that physically moving it might give me a new point of view. Then I stickytaped the bits together in a different order, with handwritten sections in between. This produced a weird-looking thing, bristling with frills and fringes.

I was panicking. I was working on the book at night now, and getting up at dawn at the weekends to rearrange things one more time. I even dreamt about it: myself on a launch on the Hawkesbury River, the water black, someone beside me not listening as I tried to explain that we have to go back, we have to go back. I woke up panting. Go back, where?

One night in October 2002, I went for my usual walk. I loved walking at night, even though it meant I had to stick to the well-lit streets. There was something about stepping out the front door into the dark, pulling it closed behind you, setting off down the street. I had some handweights that were supposed to be good for your arm muscles. I didn’t know if they were, but they made you walk in a certain way—striding out. I had a good pair of walking shoes, plenty of bounce in the soles. I had a routine: swing out of the front door at eight-thirty, walk up to the pub at the roundabout and back, a good forty-minute workout.

It had been raining on and off all day, but now the rain had become hardly more than a mist. The drizzle made a radiant halo around every streetlight. Their reflections were bright blurs along the black road. I could feel the moisture settling in my hair, weighing it down, a drip starting down the side of my face. I could have brought an umbrella, but what did it matter, it was only water. As that Irishman in Tim Winton’s book says, ‘Afraid of a bit of soft weather then?’

After a few minutes I was warmed up and striding out. At the crossroads there was an ugly cairn, a bit too squat to be glorious, erected in honour of some past local worthy. His name was there in big carved letters: THOMAS STEPHENSON ROWNTREE 1902. I imagined them all standing around at the unveiling. Speeches. Women in big silly hats. Men in waistcoats and watch-chains. The friends and family of Thomas Rowntree, admiring his name carved in stone. For ever, they’d have thought. They’ll always remember him.

Drops of water pattered in the fig trees around the cairn and I could hear fruit bats up in the branches. A spray of water came down as they made a bunch of leaves twitch. Poor old Thomas Rowntree, long forgotten. Only the fruit bats and the summer rain and this sweet cool air were still there.

I walked fast, feeling my feet springing along against the soles of my shoes. Past the video shop, where I waved hello to Amanda behind the counter. Past the hardware shop that always had a joke in its window. ‘My wife uses the fire alarm as a timer.’ Ha ha. Along the spooky bit where the streetlights were too far apart and the houses were always in darkness. Up to the pub at the roundabout, all those people laughing and shouting at each other and a cosy fug of beer smells leaking out the door, then turn back towards home.

I’d been in a pleasant moving trance with the rain on my skin and the footpath making a little wet sound at each step. I hadn’t been thinking about anything at all, much less that recalcitrant book sitting on my desk.

So why was it that, at the moment I put my hand on the front gate to push it open, I saw exactly what I needed to do? It was so simple. Get rid of William and Sophia Warner. Cut them out, kill them off.

Next morning, pen in hand, ready to cross out entire scenes, I could see what the problem was. I had two different stories in one book. One was a story about settlement—Wiseman and his family and their relationship with the Aboriginal people. The other was a classic revenge-and-romance story—Wiseman plotting over many years to square things with Warner and get Sophia.

I knew there was nothing wrong in principle with two stories in one book. But these two didn’t make a happy marriage. The first was a sombre story based on real, tragic events. The second was a lightweight, contrived thing. Neither looked good in the light of the other. It was like eating steak and fairy floss together.

When it came to drawing a line through the words, though, and removing that part of the book, I couldn’t seem to do it. Sophia was such a likeable character. That scene in the churchyard, where she and Wiseman had a cuddle, so moving. Perhaps I could make it work. One more list? One more lot of sticky notes on the window?

I remembered a trick I’d learned writing a previous book. I made a folder called ‘Good Bits To Use Later’. I got out my big scissors again, literally cut Sophia and William Warner out, and put them into the folder. It was a grief to lose such a juicy plot, and the character of Sophia, but I knew it was a necessary sacrifice.

Straight away it was as if chains had dropped off the story. The Wisemans and the Aboriginal people were left alone to get on with it, staring at each other up there on the Hawkesbury. It was just the two of them, working it out together, and that was what the story was. White meeting black, black meeting white, and everyone trying to decide what to do.

The slash and burn approach to writing: try anything, and if it doesn’t work, try something else.

There were still plenty of problems to be solved, but for the first time since I started writing, nearly two years earlier, I thought I might have a novel.