CHAPTER TWO “A Sort of Dead End”

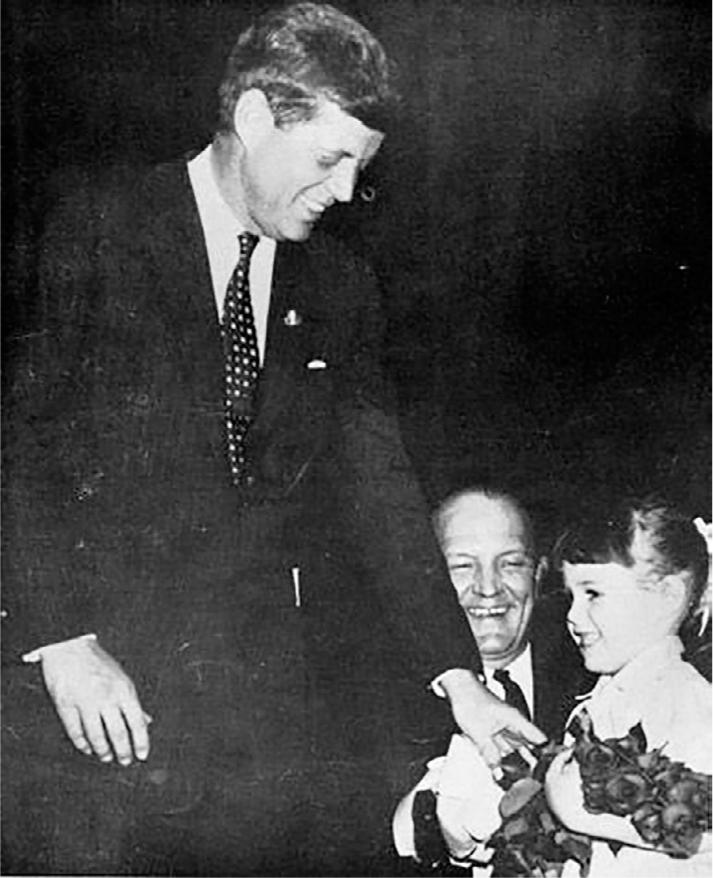

Six-year-old Ellen Anich presents a bouquet of roses to Senator Kennedy in Ashland, Wisconsin. March 17, 1960.

I BEGAN TO FEEL A sense of foreboding as our time-traveling adventure reached the threshold of the Sixties. Some thirty archival boxes covering Kennedy’s campaign were stacked in more or less chronological order in Dick’s study, their precise contents neglected for many decades. Both of us looked back upon these years with a decided bias. And our biases were not in harmony.

During his twenties, Dick had the chance to join the small, select group surrounding John Kennedy, who would become the youthful face of leadership for a new generation. Into his old age, Dick had retained a loyalty to John Kennedy, as well as an enchanted memory of his introduction to the often brutal world of politics.

In my twenties, the chance to work in Lyndon Johnson’s White House and accompany him to his ranch to assist on his memoirs had left a permanent imprint on my life. During these early years, I developed an empathy for and loyalty to Lyndon Johnson that has lasted all my life.

A fault line between the Johnson and Kennedy camps had opened with the blowback following Kennedy’s choice of LBJ as his running mate. This rift had deepened in the wake of Kennedy’s assassination, and erupted with seismic force when Robert Kennedy chose to challenge LBJ for the presidential nomination in 1968.

Tremors from this division ran through our marriage, at times provoking tension as I repeatedly insisted that the great majority of Kennedy’s domestic promises and pledges found realization only under Johnson, while Dick repeatedly countered that Kennedy’s inspirational leadership had set a tone and spirit that defined the decade. “Had Kennedy lived,” Dick would say, “the war in Vietnam—” Straightaway, he stopped himself: “Who knows?”

Our squabbles over the relative merits and demerits of the two administrations had such lasting power over us because they were neither academic debates nor historical assessments. Beneath all such arguments dwelled a clash of loyalties both of us had established before we met.

Thus, with Dick in his eighties and me in my seventies, we resolved to start from scratch as we opened the boxes, to scrape away these fixed opinions, the defensiveness and prejudices that had accumulated over the years, to see what firsthand evidence we could unearth.

“Let’s set some ground rules,” I said. “Let’s start with our first impressions of John Kennedy and see how they changed over time.”

“A clean slate,” Dick exclaimed, and reached out his hand to shake mine. As we shook hands, we both burst out laughing.

AUGUST 1956

I never met John Fitzgerald Kennedy in person. I first encountered him on our black-and-white ten-inch television screen. As it turned out, television was the most winning way to be introduced to his charms. I was thirteen years old. It was a Friday afternoon in the middle of August 1956. I was in my bedroom reading when my mother called me downstairs so I could witness a grand moment that was about to take place. I was happy to hear an unusual animation in her voice. She told me that in a wholly unexpected move, the Democratic presidential nominee, Adlai Stevenson, had thrown the selection of his running mate to the floor of the convention—and that it looked like her choice, the handsome young Catholic senator from Massachusetts, was on the verge of winning.

From the small screen came the sounds of whooping and hollering, the confusion and din from a crowd numbering in the thousands, as if some tremendous sporting event were taking place. Before long, I was curled up on the sofa alongside my mother’s chair, trying to keep score on a big piece of poster board. The magic number to win, the commentators kept repeating, was 686 ½. The rules of this game were far more peculiar than those of my accustomed, orderly universe of scoring baseball games with my father which progressed play-by-play, out-by-out, inning-by-inning. Here, numbers rose and fell as states waved their standards in the air, howling for recognition to announce their tallied votes, which somehow shifted from one candidate to another in the space of fifteen or twenty minutes.

At the time, I knew almost nothing about conventions. My parents were not especially active in politics. At the dinner table, politics was discussed no more than money or sex. All I knew was that my mother rarely showed the sense of vitality and elation that was apparent that afternoon of the Democratic convention. Rheumatic fever as a child had left her with a damaged heart. Angina attacks had begun in her thirties. Three summers earlier, a major heart attack had taken a permanent toll on her body. But on this day, her eyes were bright and her voice was strong.

She explained to me that even though the senator from Tennessee, Estes Kefauver—I’d never heard the name Estes before (to say nothing of Kefauver), and it struck me as funny—had led after the first ballot, Kennedy, showing a surprising momentum, had come in second, ahead of Senators Hubert Humphrey and Albert Gore Sr. And sure enough, on the second ballot, my mother’s young Irish prince jumped into the lead—and she jumped to her feet and cheered.

Midway through the second ballot, after New York delivered big for Kennedy, I had my first glimpse of a long figure with big ears. It was Lyndon Johnson. He grasped the microphone and shouted that Texas would cast its entire vote total for John Fitzgerald Kennedy. Banners waved. Shouts for Kennedy filled the air. Ahead of Kefauver now, Kennedy was within 20 ½ votes of victory. Tension mounted in the amphitheater and in our family room.

What happened next made no sense to me. Senator Gore of Tennessee requested that his name be withdrawn in favor of Kefauver. All of a sudden, the incoming tide for Kennedy abruptly stopped. Then the tide ebbed as one state after another snatched their votes away from Kennedy and delivered them to Kefauver. It seemed ridiculous, as if my Brooklyn Dodgers had scored two runs in one inning, before both were suddenly taken away the next inning and given to the Yankees. Soon, Kefauver was safely beyond the magical 686 ½, my disappointed mother was close to tears, and I was angry at what seemed an utterly mystifying affair.

That was when the defeated candidate stepped to the rostrum. My mother and I both fell silent. He didn’t look like anybody else up on the speaker stand, so slender, so young, with his full head of hair. His face looked weary. I could tell he was sad. But he maintained an earnest and graceful control in accepting defeat. He thanked his supporters from all over the country. He praised Stevenson for his “good judgment” in letting the convention select the vice presidential nominee, and, finally, asked the delegates to nominate Kefauver by acclamation. As Kefauver made his way into the convention hall to the strains of the “Tennessee Waltz” and the roar of the crowd, the television camera switched instead to a close-up view of Kennedy collecting himself in the aftermath of defeat, standing tall and clapping for Kefauver. Indeed, there was something in the vulnerability he displayed, his magnanimous demeanor, that transformed my mother’s sorrow into pride, and suspended my own anger and bewilderment in favor of a newly minted curiosity.

More than six decades after watching Kennedy’s concession speech with my mother, I replayed that day’s proceedings on YouTube. In the years since, I had become familiar with the ebb and flow of delegate tallies. I had come to understand that when Senator Gore withdrew and the midwestern and Rocky Mountain states held firm for Kefauver, Kennedy had likely reached the limit of his support; once that situation became clear, a bandwagon effect in favor of Kefauver had set in. No one wanted to be on the wrong side after the finish line had been crossed.

In the decades afterward, I had studied and written about both JFK and LBJ. I knew that in contrast to Kennedy’s praise of Stevenson’s “good judgment” in allowing the convention to select the nominee, LBJ considered the decision “the goddamndest stupidest move a politician could make.” As I watched a video of the convention online, I listened carefully to the words Johnson used when he delivered the state of Texas for Kennedy: “Texas proudly casts its fifty-six votes for the fighting sailor who wears the scars of battle, the fearless senator, John Fitzgerald Kennedy.” I could not help but smile, for these flattering words were in stark contrast to the image LBJ had painted of the junior senator for me one day at the ranch, calling him “a young whippersnapper, malaria ridden and yellah,” who “never said a word of importance in the Senate” and “never did a thing.” Such feelings mattered little, I now understood. For the Texas delegation, anyone was preferable to the outspoken liberal Kefauver. And Johnson believed that Kennedy had the best shot at beating Kefauver. Furthermore, in a political era marked by the rise of television, Johnson acknowledged that “Kennedy looked awfully good on the goddamn television screen.”

My mother and I were alone in our house that summer afternoon, but the impression Kennedy made on the two of us was shared in all parts of the country by millions of people. It was this realization that struck me most forcibly during my recent rewatch of the convention: the power of television to ignite a personality in a single moment, transforming a young senator into a national figure, conveying an impression of vitality, excitement, and promise that would linger and grow in the years ahead.

MARCH 1958

Curiously, the romantic aura surrounding John Kennedy that both my mother and I had felt via television in 1956 was nowhere in evidence in March of 1958 when Dick first encountered the young senator in the flesh. A kind of introductory interview had been arranged by Sumner Kaplan, the state representative from Brookline who had championed Dick’s first foray into politics during the rent control struggle and the fight to prevent discrimination in local fraternities and sororities. Sumner would become a lifelong friend and mentor to Dick.

Dick only had a vague memory of a chilly spring day and trudging up three flights of stairs to a cramped, shabby apartment at 122 Bowdoin Street in Boston. This tiny apartment—across from the State House and next to the Bellevue Hotel where local politicians gathered—had been Kennedy’s official Boston residence since his first run for Congress twelve years earlier. An outer room was crowded with local politicians and lobbyists. After twenty minutes, Kennedy’s aide, Frank Morrissey, showed Sumner and Dick into an adjacent room, where Kennedy greeted Sumner warmly and shook Dick’s hand.

“I understand you’re going to work for Frankfurter,” Kennedy said, and then with a shrug and faint smile, added, “He’s not my greatest fan.”

“Kennedy remained standing,” Dick told me, “and so, of course, did we. Then, with a skill that did not signal dismissal though indeed that’s exactly what it was, Kennedy waved to a small group of men Morrissey was bringing into the room. Almost simultaneously, Morrissey reached for Sumner’s arm to escort us to the door. But before we left, Kennedy took my hand a second time and, meeting my eyes, said simply, ‘I’ll be looking for people in January once I finish my reelection campaign. Come and see me.’ We weren’t in there very long.”

Dick’s description reminded me of Theodore Roosevelt’s rapid-fire meetings with visitors when he was governor. It was said that his stately desk might well have been removed altogether for he was always standing, receiving and dismissing record numbers of visitors so adroitly that each person somehow felt he had truly and personally engaged with him.

A few days after the Bowdoin Street encounter, Dick wrote George Cuomo:

I recently had an interesting meeting with Senator Kennedy when he was in Boston. He intimated strongly that he would like to have me come to work for him next January after he finishes running for re-election for the Senate.

However, even if he wants me to work—and this is not at all certain—I am not sure. Work for him, no matter how interesting, is bound to be a sort of dead end for one so young.

“A dead end? So you thought, at twenty-six, you’d be stuck in some sort of Senate cubicle forever?” I asked.

“I’m not sure what I thought. Only that there was nothing intoxicating about the senator or his confining quarters. The size and impression of the place should have no bearing on the size of its occupant—but of course it does.”

JANUARY 1959

After the dust of the Senate reelection campaign had settled, Dick followed up on Kennedy’s invitation. Kennedy had been reelected by a historic, whopping 73 percent of the vote. This second meeting took place not in the cramped Bowdoin Street apartment above a cobbler’s shop, but in the grand and formal setting of the Old Senate Office Building. The senator’s office, Room 362, was across the hall from the Senate office of Vice President Richard Nixon.

“I don’t know,” Dick told me, “whether it was the regal Old Senate Office Building, Kennedy’s resounding reelection to the Senate, or the crackling electricity generated by his impending presidential bid, but the atmosphere that day was charged.”

After passing the hive of activity surrounding the secretarial desks—clacking typewriters, ringing phones, competing voices—Dick was guided into the relative tranquility of Kennedy’s inner office. This time, Kennedy rose from behind his desk to shake hands and ushered Dick to a leather chair opposite the desk. This was not simply a Teddy Roosevelt meet-and-greet.

“He seemed different, more impressive,” Dick recalled. “He asked me all kinds of questions about my experience at Harvard Law School, about my work on the court, reiterating that Justice Frankfurter was not one of his supporters.”

Dick wisely chose not to enter into a conversation about the Justice. He knew that Frankfurter despised Kennedy’s father, Joe, believing him an anti-Semitic Nazi appeaser during the early days of World War II. Frankfurter considered young Kennedy a lightweight.

“The conversation lasted twenty minutes or so. It was genial. He was sizing me up. His curiosity felt genuine. I didn’t feel uncomfortable. I doubt I had grown much in size since the first meeting, but I felt certain that he had. The strongest impression he made was of a powerful, disciplined ambition.”

“Were you projecting all this on him, imagining him as president,” I wondered, “or was it actually emanating from him?”

“I’m not sure,” Dick said. “All I know is that I was sufficiently engaged to tell him straight out that once my time as a law clerk was over, I would like to help in the campaign that was brewing in his offices. No commitment was made. He simply said keep in touch, but my guess was that my name was put into a file of potential staffers when the Kennedy team for a presidential run was assembled.”

Perhaps, I later thought, it was from this file that Ted Sorensen picked Dick’s name to enter the contest for the post of junior speechwriter.

DECEMBER 1959

“There were no swimming lessons on that job,” Dick laughed. “Ted Sorensen handed me folders overflowing with memos, articles, and various background materials on arms control, something I knew next to nothing about. He showed me to a desk in an outer room of the Senate office, and with a brief, ‘I’ll stop by later, we need the article for tomorrow,’ he threw me in the swimming pool to fend for myself and left.”

Throughout that first day, Dick pored over position papers, suggestions from a variety of advisers and academics, as well as every public statement Kennedy had made on the topic. Dick had always been a quick study, adept at scanning and cramming, yet somehow also able to distill an immense mass of material into something clear and clean. He told me, however, that as the hours passed and he began to peck out a draft of several thousand words on his typewriter, the work made law school begin to feel like a romp in kindergarten.

By the time Sorensen reappeared to pick up the pages Dick had produced, everyone else had left the office. Sorensen read through the draft while standing. “Not bad” was all Dick remembered as an introductory compliment. Then, Sorensen pulled up a chair, and for the next hour or more, underlined and slashed Dick’s pages, his crisp and vigorous mind pointing out the slightest deviations from Kennedy’s policy positions while also tightening the syntax to suggest the clipped mannerisms Kennedy favored. No sooner had he finished this intense tutelage session than he rose, slid back the chair, picked up his briefcase, and, turning to Dick, said, “It still needs work and we still need it by tomorrow. Good luck.” And then he was gone. So Dick’s first day in the office led to his first long night of coffee and cigars, working until dawn.

Sorensen, chief of the speechwriting team, and Dick, the sorcerer’s promising apprentice, made for an odd couple. It would be difficult to find two more different characters than Dick and Ted. The mentor, immensely helpful, yet sparing in praise, undemonstrative, guarded, and possessive of his long, exclusive relationship with Kennedy; the student, idealistic and emotional, bright and ambitious. Although Sorensen seemed at least a decade older than Dick, in actuality, only three years separated them. For the prior half dozen years, Sorensen had been Kennedy’s sole speechwriter, intellectual and policy sounding-board, adviser, and traveling companion as they had toured every state of the Union.

If conceivable, Sorensen would never have tolerated an assistant speechwriter at all, but the need to generate material for the fledgling campaign had grown to the point where it was no longer possible for him to produce the material that was necessary on his own.

JANUARY 1960

On January 2, 1960, hardly a month into the job—in the immediate aftermath of Kennedy’s announcement of his candidacy for the Democratic presidential nomination—Sorensen gave Dick a chance to collaborate on an assignment that was different from the usual articles and position papers. He told Dick that Kennedy wanted to make a speech on the presidency itself. He wanted to draw a line between the complacent, passive presidential leadership of the Fifties, and the progressive, active conception of the presidency that he felt certain the new decade of the Sixties required and that he intended to offer. On that collision between active and passive, old and new, between what he would do in the coming decade and what had not been done in the previous, Kennedy had decided to wager the identity of his campaign.

Dick remembered rushing with Sorensen to deliver the speech draft to Kennedy, in transit from one city to another, at Butler Aviation Terminal in Washington, D.C. “That presidential draft was the first time I had ever observed him read a speech I had worked on. Quick marks with his pencil, nothing encouraging or discouraging, but there was a remarkable intensity of focus. He said he didn’t mind “sticking it to old Ike,” so long as the immensely popular president’s name was not mentioned.

Rifling through Dick’s boxes, we found an advance copy of the speech, given on January 14, 1960, before the National Press Club in Washington. As we carefully reread the speech, what surprised me most was that it spoke of “the challenging, revolutionary sixties,” forecasting the future of a decade then little more than two weeks old!

“What do the times—and the people—demand for the next four years in the White House?” The speech suggested that they demanded an active commander in chief, “not merely a bookkeeper.” They demanded “more than ringing manifestoes issued from the rear of the battle.” They demanded that the president “be the head of a responsible party, not rise so far above politics as to be invisible.”

These biting phrases were so transparent that they seemed to me to clearly cross the line of not directly criticizing Eisenhower. Apparently at the last minute, Kennedy made a similar assessment. A journalist who had seen the advance press release recognized that when he delivered the speech, he “pulled his punches.” He dropped the critique of a passive leader fighting from the rear of the battle. And he eliminated the demeaning “bookkeeper” reference. Nonetheless, the speech was pungent enough to elicit a most unusual round of applause from the press corps.

What I liked most about the speech was that history formed its spine. Quotes from past presidents were sprinkled throughout as they would be in nearly all the work Dick crafted during his speechwriting career. Looking back, I was particularly fascinated to note Kennedy’s desire to mold his future presidency in the expansive tradition of Franklin Roosevelt, Theodore Roosevelt, and Abraham Lincoln—“my guys,” the presidents with whom I had spent decades of my life. Indeed, Kennedy’s speech ended with Lincoln’s statement after signing the Emancipation Proclamation: “If my name ever goes into history, it will be for this act, and my whole soul is in it.”

After we had finished reviewing this speech, eighty-four-year-old Dick waxed nostalgic: “So there I was,” he said, “twenty-nine years old, a history major in college, summoning my passion for the story of America into my first speech for Kennedy in those first days of the Sixties.”

“And there I was,” I added, “a seventeen-year-old high school senior, dreaming of becoming a high school teacher. You, dreaming of changing history; me, of teaching how those changes were made.”

In 1960, the only path to the Democratic nomination for John Kennedy was through the primaries. He was not the darling of the party bosses. Given his age, inexperience, and Catholicism, they had serious doubts about his ability to win the general election.

Kennedy knew there were not enough primary votes to secure his nomination. The primaries did, however, offer a proving ground, an opportunity to audition for the power brokers of the Democratic Party—to demonstrate, in a trial of popular appeal and strength, his viability as a candidate.

From the moment he had announced his intentions on January 2, he had issued the challenge that “any Democratic aspirant to this important nomination should be willing to submit to the voters his views, record, and competence in a series of primary contests.”

Hubert Humphrey was the only rival to take up Kennedy’s gauntlet, although Stevenson, Missouri senator Stuart Symington, and Lyndon Johnson waited and watched from the wings.

When I asked Dick to tell me about the primary trail with the senator, he said, “Mostly I wasn’t there! I was holed up day and night in his Senate office in Washington, an overheated cog in a promise-and-pledge machine.”

Dick became adept at Sorensen’s tripartite formula of a stump speech, recognizing how a stock opening and closing of every speech would sandwich the meat of what the candidate might promise to persuade that particular audience. It was this formula that enabled him to churn out a variety of stump speeches with great speed, transforming hitherto inscrutable questions concerning wheat markets, coal extraction techniques, and dairy supports into somewhat coherent proposals and pledges that might be accomplished in the future. And of course, there were general patriotic and partisan themes, such as a great America could be even greater.

As Dick and I searched through a sampler of these stump speeches, he estimated that he had written about 40 percent of them. And how dense they were!—he hefted onto the table a stack of stump speeches, fact sheets, position papers, and assorted files. “Wow… not so profound maybe,” he said, “but I was goddamn prolific.”

Afterward, we read a few of them aloud. “Pretty dull,” I said to Dick.

“Exactly,” Dick nodded, “but designed to show that Kennedy was not a lightweight. He had command of hard facts and issues. He had gravity.”

Dick had to assimilate reams of position papers in order to fashion informed statements—about agricultural policy for the South Dakota plowing contest, about timber in the Northwest, about water in California, about hard and soft coal in West Virginia, and about dairy programs for farmers in Wisconsin. After working on a farm speech with the candidate, Dick recalled Kennedy remarking, “Here we are, two farmers from Brookline.”

Promises and pledges were the steady drumbeat of Kennedy’s stump speeches, variously tailored for a Jewish community center, a grange, a high school auditorium, a luncheon, or a brief after-dinner speech: “We pledge ourselves to passing a water control bill… to a program of agricultural research… to preserve the fish which inhabit our lakes… to assist small businesses to get a larger share of defense contracts… promise to strengthen and expand employment services to assist displaced men to find better jobs…” His proposals, pledges, and promises to build a dam or dredge a harbor accumulated until, by the campaign’s end, Dick compiled a list of more than eighty-one pledges.

While Kennedy was trying to prove himself to the party bosses, he was also learning how to better speak to people crowded before him. It was often difficult to comprehend his accelerated mode of delivery and clipped Boston accent. Dick had kept a copy of a taped interview with Robert Healy, a friend from The Boston Globe, who covered Kennedy during the 1960 race. In the early days, Healy recalled, the candidate wasn’t a “polished speaker. He spoke so rapidly that nothing really sank in.” He raced through his prepared speeches like a young kid giving a report who was eager to get back to his seat. But he excelled during question-and-answer periods, and came across as articulate, informed, and often humorous.

And most impressively, Healy noted, Kennedy actually sought criticism. He would ask reporters all kinds of questions about the crowd’s reaction. Did they seem to like him? When and where did their attention drift? Where were they enthusiastic?

“So of all this stuff you and Sorensen helped concoct for the primaries,” I asked Dick, “what has stayed with you?”

“Ashland,” Dick responded without hesitation, “Ashland, Wisconsin. I remember drafting a pledge for Kennedy’s visit there, a promise to clean up the harbor and provide federal aid for this small town on the shores of Lake Superior that was down on its heels. Manufacturing was gone, jobs scarce, a polluted harbor. I’m not sure why,” Dick said wistfully, “but over the past half century, I’ve often wondered about Ashland. I even wanted to go there to see what happened to that harbor, but I never made it.”

Dick’s words echoed in my head as I continued sifting through the archive to explore material relevant to the 1960 Wisconsin primary, the first of the competitive primaries (Kennedy had easily won New Hampshire, his neighboring state). I resolved to find the answer to Dick’s old question: What had happened to Ashland? Had Kennedy’s pledges been fulfilled? Or were they only so much political bluster? The answer turned out to be more complicated than I had imagined.

Curious, on a whim, I called the Ashland Historical Society and reached out to longtime residents. I dug up old newspaper clippings spanning the decades from 1960 to the present. I reread Theodore White’s The Making of the President 1960, which I had first encountered six decades earlier in graduate school.

MARCH 1960

According to White, who shadowed Kennedy during the Wisconsin primary, the candidate had reached Ashland on March 17, 1960, at the close of a long, grueling day that had begun at dawn in the city of Eau Claire. Only eight people showed up for a rally planned at a roadside diner. Driving north through the sparsely populated region, a hatless Kennedy jumped from his car in village centers, walking through the streets, extending his hand to the few passers-by. Unheralded, he slipped into country stores, saloons, and factories, where he was often met with grunts or stares. “I’m John Kennedy,” he would say, “candidate for president. I’d like to have your vote in the primary.” One worker replied, “Yeah! Happy New Year.” This was Humphrey territory. Minnesota was a neighbor, and Humphrey was known and well respected in Wisconsin.

The image of what White described as “a very forlorn and lonesome young man” walking through the streets stuck in my memory. White was impressed by Kennedy’s resolution and perseverance. Neither the ten-degree temperature nor the wall of indifference dispirited him. “He had not even once,” White reported, “lost his dignity, his calm, his cool, and total composure.”

Compared to the grim day of hunting out voters throughout the depressed Ninth and Tenth Districts, the evening event in Ashland was a revelation of warm possibility. Organizers had filled the Dodd Gym with seven hundred people. Before Kennedy spoke, six-year-old Ellen Anich crossed the stage, carrying a bouquet of flowers she had brought to present to the candidate’s wife, Jackie Kennedy.

That six-year-old girl was now sixty-eight when I tracked her down for a conversation.

“A bunch of grayheads sitting around the table thought it would be cute to have a little girl deliver the flowers. My uncle, Tom Anich, was active in Democratic politics,” Ellen explained, “so I was chosen. We had no money. Everything I wore belonged to a rich girl across the street. That day, I practiced handing things over…. But when Kennedy reached down to accept the flowers in his wife’s absence, I held back, confused since they were meant for his wife.”

Kennedy explained that his wife was pregnant and resting. “My mom’s going to have a baby, too,” young Ellen announced.

“I promise if you give them to me, I will make sure she gets them,” Kennedy assured her—so finally, she surrendered the roses.

The crowd roared with good-natured laughter, sending the night in a positive direction. The high spirits continued as Kennedy spoke of a Democratic bill Eisenhower had vetoed, the Area Redevelopment Bill. He pledged that he would work for its passage so that Ashland and other depressed communities throughout the country would receive the aid they deserved from their government.

On September 24, 1963, Kennedy returned to Ashland, this time as president of the United States. The harbor had not been cleaned up and the grave economic situation had not improved. As president he had passed and signed the Area Redevelopment Bill, but its modest funds had not filtered down to Ashland.

Nonetheless, that presidential visit, the start of an eleven-state conservation tour, would be widely remembered as “the greatest day in Ashland’s history.” Schools were closed and a holiday mood prevailed.

“It was a big honor for our little town,” Ellen’s ninety-one-year-old aunt, Beverley Anich, told me.

A radio recording captures the tremendous thunder and screaming of the crowd as Kennedy emerged from a helicopter that had set down at the small airport. “Everyone is most excited,” the announcer said, “for the President of the United States to step foot on our land.” On his way to the speaker’s stand, Kennedy veered suddenly toward the snow fencing, behind which some fifteen thousand people (a crowd larger than the whole of Ashland’s population) had gathered.

I could not help but contrast the pandemonium that greeted him that day as he reached across the fence to shake as many outreached hands as he could (much to the dismay of the Secret Service) with the icy reception he had received three years earlier when hunting down votes one by one in the deserted streets of northern Wisconsin.

He issued a clarion call for the preservation of natural resources, for protecting freshwater harbors, lakes, and streams, and once again promising government aid. He spoke of plans for making the nearby Apostle Islands into a national park. His speech lasted only ten minutes. After mixing with the crowd, Kennedy’s military helicopter left from the airport that would soon be rededicated in his honor. Yet, even his brief visit, I would discover, had left an impression on the people of Ashland that would continue to inspire them for years to come.

Fifty years to the month after Kennedy’s 1963 visit, a reporter interviewed a number of the people the president had encountered that day. Rollie Hicks was a math and physics major at Northland College. He had little interest in politics, but his friends convinced him to go to the airport. When Kennedy was returning to his helicopter following his speech, he made another abrupt turn toward the fence at the very spot where Rollie was standing. “He shook my hand and I gave him a Northland College booster pin.” Looking back, sixty-nine-year-old Rollie said he didn’t want to overplay it, but something happened on that day that was instrumental in leading him to a life of politics and public service.

And by all accounts, Rollie’s experience was not unique. There was an aura surrounding John Kennedy that altered the paths of countless young men and women. One, named Temperance Debe had a similar experience. Kennedy introduced himself and took her hand. “All I could think about is how perfect he looked,” the seventy-three-year-old recalled, “his smile, his hair, his suit.” Though stunned into silence at first, she summoned the courage to introduce herself, telling him that her friends called her Tempe. “Then I will call you Tempe,” he said. He then asked her questions about her life and listened carefully as she told him she lived at the Fond Du Lac reservation. He wanted to know about the reservation. “We need people like you,” he told her before taking his leave. That day, she told the reporter, marked a change in her life. “I felt anything was possible.” Tempe went on to get an associate degree, a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in social work. She was a founder of the first preschool program at Fond Du Lac and worked to address mental health issues for Native Americans.

I am not suggesting a causal chain of events, but pointing out an organic narrative that emerged again and again from various witnesses’ accounts.

As I talked with seventy-three-year-old lifelong Ashland resident, town historian, and former mayor Edward Monroe, an answer began to surface to Dick’s question about what had happened to Ashland’s harbor and economy.

“It was a very depressing place in 1963,” Monroe said. He explained that an abandoned saw mill had left wood pilings close to shore. It all looked like ruins from a war. The Dupont plant, which had made dynamite and TNT, had shut its doors, but not before an accumulation of discharged chemicals had turned the lake blood red. Waste from the paper mill had left a milky sheen on the bay. The coal power plant had dumped a tarlike substance in the harbor.

“It’s been a very long road,” Monroe told me, “but I believe it began with the president’s visit to our little town. Talk to anyone in Ashland who was there and they will remember every detail. He made us feel good about ourselves. We needed to feel good about ourselves to believe we could make our town better. He had challenged the country to put a man on the moon. Now he was challenging us. Little by little we began to clean up the harbor and the beachfront.”

The town was awarded a grant to remove those wood pilings from the shore. A pedestrian tunnel was built to give residents a way of getting from the downtown plaza to the lakeshore without crossing a busy highway. A small community project to paint a few murals on the tunnel walls mushroomed to create 250 murals that now span the entire tunnel. A hospital grew into a medical campus that today houses both cancer and mental health centers that serve seven counties.

And, after decades of legal battles, a federal court finally identified those responsible for the pollutants carpeting the harbor floor. That legal settlement created a multimillion-dollar Superfund to dredge the bottom and clean the harbor.

“The harbor is in good shape,” Monroe proudly noted. “The beachfront is restored. Tourists are coming here. You would not recognize Ashland today from the down-and-out place it was six decades ago.”

The legislative aid Kennedy had promised in the campaign had not been delivered to Ashland. It had taken more than half a century and a cascade of intervening events to clean up Ashland’s harbor and strengthen the town’s economic life.

Yet, it seems clear to me that something indefinable had happened when President Kennedy came to Ashland, that his presence had inspired in the townspeople a belief in themselves that had helped set in motion the long journey toward their community’s revival. The abandoned industrial plants had left behind a dispiriting gloom as well as an ugly physical residue. Kennedy’s visit generated the beginnings of a new mindset.

“We felt after he was here that we were more than we were before,” Edward Monroe told me. “We began the projects that long needed to be done.”

In the long run, the aspirations and inspiration that Kennedy had brought to Ashland may well have proven every bit as vital to leadership as policies and programs. It was a point, I came to understand, that I had never properly realized or conceded to Dick.

APRIL 1960

Kennedy’s long days of trudging through Wisconsin paid off on April 5, primary day. He never developed the boisterous and friendly chumminess, the genial touch of Hubert Humphrey. There was always a distance, as if something was withheld, setting him apart and making him less accessible. In the end, that line was perhaps not a liability at all, but a strength.

His victory over Humphrey, however, was not the knockout blow the campaign had anticipated, and the votes, once tallied, revealed a troubling religious split. Kennedy took the predominantly Catholic districts; Humphrey easily won the predominantly Protestant districts.

“What does it mean?” Kennedy was asked. “It means we have to do it all over again. We have to go through every one and win every one of them—West Virginia, and Maryland and Indiana and Oregon, all the way to the Convention.”

And so their marathon sprint went on to West Virginia. Day and night, Dick remembered, he tried to make sense of hard coal, soft coal, coal by wire, and burning fuel. Only Catholicism was taboo for the speechwriters. Kennedy decided to address the issue himself in Charleston, West Virginia, when he spontaneously responded to a question about his religion: “The fact that I was born a Catholic, does that mean that I can’t be the president of the United States? I’m able to serve in Congress, and my brother was able to give his life, but we can’t be President?” The real issues, he repeatedly argued, were poverty, unemployment, and what could be done to make daily life better for the people of the state.

On May 10, West Virginia’s primary day, Kennedy beat Humphrey by an overwhelming margin. In the weeks that followed, Kennedy swept the rest of the primaries. In so doing, he demonstrated to the political bosses that a young Catholic could mobilize the support of the American people across the country.

JULY 1960

On the night of Wednesday, July 13, Kennedy secured his party’s nomination on the first ballot at the Democratic convention. On Thursday, the convention delegates (not to mention Kennedy’s inner circle) were stunned when Kennedy announced that he had chosen Lyndon Johnson as his running mate. Dick had remained in Washington during the convention. I wondered what he and his colleagues in the office had thought when they first heard the news that Lyndon Johnson was suddenly part of their team. Dick said he remembered a general feeling of disappointment and confusion.

“I guess in a sense we’d all profiled him,” Dick admitted. “He was from the South, immediately suspect on matters of civil rights. We knew of labor’s disapproval. He seemed old, a figure from the past, not a member of the new generation that was at the core of our campaign.”

Kennedy had promised that he would seek out new men who would “cast off the old slogans and delusions and suspicion.” If Lyndon Johnson seemed to balance the ticket, the perceived conception was that he did so from the right and from the past.

And yet, Dick recalled, in the many months of all-nighters in the Senate office during the primaries, no matter how far past midnight he stayed at the office, he was sure to spy a single light in the darkened Capitol building shining from the office of the Senate majority leader. “It shone like a beacon in a lighthouse. I thought maybe Lyndon had left that light burning to fool people into thinking he was always working. The day would come when I learned that my surmise was wrong. He was always working.”

There are warring narratives as to what really happened in those hours between Kennedy’s nomination and his surprise selection of Lyndon Johnson as his running mate. Some observers claim Kennedy’s offer was simply a gesture made with the certainty that Johnson would never surrender the power of Senate majority leader for the hapless post of the vice presidency. If so, that calculation failed to understand that throughout his career, Johnson had shown an uncanny ability to turn a sow’s ear into a silk purse. As party whip, minority leader, and majority leader, he had taken positions with small bases of power and vastly magnified and multiplied their functions.

Others claim that the offer to Johnson was genuine and made in good faith. Kennedy had carefully weighed the pros and cons, subtracting voters Johnson would likely lose in the North, while adding votes he would gain in the South. In the end, he could not see his way to victory without Johnson. Without Texas, he had an insufficient number of electoral votes.

Lyndon Johnson, an inveterate nose-counter, was doing his own arithmetic. He had even asked his staff to research how many vice presidents had gone on to become president. That number was ten. Seven of them did not have to wage a campaign, inheriting the presidency after the incumbent’s death.

Finally, it seems that when Kennedy went to proffer Johnson the post, he did not definitively make the offer, but merely suggested it. Nonetheless, Johnson readily accepted the matter as a done deal. When sufficient displeasure surfaced within the Kennedy ranks and among Democratic activists, however, Kennedy began to have second thoughts.

As John Kennedy’s unofficial surrogate, his brother Robert Kennedy was given the unfortunate job of persuading Johnson to rescind his acceptance of the candidate’s suggestion regarding the vice presidency. In all likelihood, Johnson identified Bobby as the agent and not the messenger. Bobby warned that if a nasty fight erupted on the convention floor, its fallout could well damage the launch of the entire campaign. Perhaps in compensation for withdrawal, Johnson might consider accepting the chairmanship of the Democratic Committee? Johnson stood his ground. He had been told he would be the nominee. He wanted to be vice president. To withdraw the offer publicly would be calamitous. Kennedy had no recourse but to bring Johnson’s name forward.

Robert Kennedy, Dick told me, was disconsolate about Johnson’s selection. “Don’t worry, Bobby,” Kennedy told his brother, a comment Bobby grimly confided to Dick years later, “Nothing’s going to happen to me.”

The delegates were eventually brought into line. Johnson was nominated by voice vote, but he would forever blame Bobby for the humiliation he experienced during that chaotic afternoon. Mistrust, suspicion, and a scarcely concealed hatred continued between the two men from that day forward.

So, with confusion and turmoil on both sides, the Kennedy-Johnson ticket was born. And in hindsight, without that ticket there would have been no President John Fitzgerald Kennedy in 1961, and no President Lyndon Baines Johnson in 1963.

Several weeks after the convention, Ted Sorensen paused by Dick’s desk late one evening as he was about to leave the office. “Beginning in September, you’ll be joining me and the senator on the plane for the national campaign.”

“I tried to stay composed,” Dick told me, “but I felt like I was going to jump out of my skin.”

“Maybe get a new dark suit, a few white shirts, and new ties,” Sorensen had suggested. “Something conservative.”

“I thought the other guys were the conservatives,” Dick had said, smiling.