Ricci flow is a technique that allows one to take an arbitrary RIEMANNIAN MANIFOLD [I.3 §6.10] and smooth out the geometry of that manifold to make it look more symmetric. It has proven to be a very useful tool in understanding the topology of such manifolds.

Ricci flow can be defined for Riemannian manifolds of any dimension, but for the sake of exposition we restrict ourselves here to two-dimensional manifolds (i.e., surfaces) as they are easy to visualize. From our everyday experience with three-dimensional space ℝ3, we are familiar with many surfaces, such as spheres, cylinders, planes, tori (the shape of the surface of a doughnut), and so forth. This is an extrinsic way to think about surfaces: as subsets of a larger ambient space, which in this case is three-dimensional Euclidean space. On the other hand, one can think about surfaces in a more abstract intrinsic manner: by considering how the points in the surface stand in relation to each other, but not in relation to any external space. (For instance, the Klein bottle makes perfect sense as a surface from an intrinsic viewpoint, but cannot be viewed extrinsically in three-dimensional Euclidean space ℝ3, although it can be viewed extrinsically in four-dimensional Euclidean space ℝ4.) It turns out that the two viewpoints are mostly equivalent to each other, but it will be more convenient here to adopt the intrinsic perspective.

A good example of a surface is the surface of Earth. Extrinsically, this is a subset of a three-dimensional space ℝ3. But we can also view this surface two dimensionally by using an atlas: a collection of maps or charts that describe various regions of this surface by identifying them with a subset of a two-dimensional plane. As long as we have enough charts to cover the original surface, this atlas is sufficient to describe the surface. This way of thinking of a surface is not completely intrinsic, because there is more than one atlas that one could associate with this surface, and they may differ in various minor ways. For instance, in one atlas the city of Los Angeles might be on the boundary of one of the charts, whereas in another atlas it might be in the interior of every chart that it appears in. However, there are many facts one can deduce from an atlas that do not depend on the choice of atlas; for instance, using any accurate atlas of Earth one can see that it is impossible to travel from Los Angeles to Sydney without crossing at least one ocean. If a fact regarding a surface does not depend on which atlas one uses, we say that it is intrinsic or coordinate-independent. It will turn out that Ricci flow is an intrinsic flow on surfaces; it can be defined without any knowledge of charts or of some external space.

We have informally described the mathematical concept of a surface, or two-dimensional manifold. But to describe Ricci flow we need the more sophisticated concept of a Riemannian surface (or two-dimensional Riemannian manifold). This is a surface M with an additional (intrinsic) object, a Riemannian metric g, which specifies the distance d(x,y) between any two points x,y on the surface. This metric allows one to define the angle ∠γl, γ2 that any two curves γl, γ2 on the surface make where they intersect; for instance, the Earth’s equator intersects any longitude at right angles. And it can also be used to define the area |A| of any given set A on the surface (e.g., the area of Australia). There are a number of properties that these concepts of distance, angle, and area have to satisfy, but the most important property can be stated informally as follows: the geometry of a Riemannian surface has to be very close to the geometry of the Euclidean plane at small length scales.

To give an example of what the above statement means, take any point x in the surface M, and pick any positive radius r. Because the Riemannian metric g specifies a notion of distance, we can define the disk B(x, r) of radius r centered at x to be the set of all points y whose distance d(x,y) to x is less than r. Because the Riemannian metric g defines a notion of area, we can then discuss the area of this disk B(x, r). In the Euclidean plane, this area would of course be πr2. In a Riemannian surface, this need not be the case: for instance, the total area of the surface of Earth (and hence of all disks within this surface) is finite, even though πr2 can be arbitrarily large as r goes to infinity. However, we do require that, when r is very small, the area of the disk B(x, r) becomes increasingly close to πr2; more precisely, we require that the ratio between the area and πr2 converges to 1 in the limit as r tends to 0.

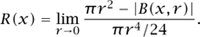

This brings us to the notion of scalar curvature R(x). In some cases, such as on the sphere, the area |B(x, r)| of a small disk B(x, r) is actually a little bit smaller than πr2; when this is the case, we say that the surface has positive scalar curvature at x. In some other cases, such as on a saddle, the area |B(x, r)| of a small disk B(x, r) is a bit larger than πr2; then we say that the surface has negative scalar curvature at x. In other cases again, such as on a cylinder, the area |B(x, r)| of a small disk B(x,r) is equal (or very nearly equal) to πr2; in this case we say the surface has vanishing scalar curvature at x. (This is despite the cylinder being “curved” when viewed extrinsically as a subset of three-dimensional space.) Note that on a complicated surface it is perfectly possible to have positive scalar curvature at some points of the surface and negative or vanishing scalar curvature at other points. The scalar curvature R(x) at any given point x can be defined more precisely by the formula

(For surfaces in an external space, this intrinsic concept of scalar curvature is almost identical to the extrinsic concept of Gauss curvature, which we will not discuss here.)

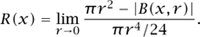

One can refine this notion to that of Ricci curvature Ric (x)(v, v). Consider now an angular sector A(x, r, θ, v) inside a small disk B(x, r) of small angular aperture θ (measured in radians) about some direction v (a unit vector) emanating from x. This sector is well-defined, basically because the Riemannian metric gives us the appropriate notions of distance and angle. In Euclidean space, the area |A(x, r, θ, v)| of this sector is  θr2. But on a surface, the area |A(x, r, θ, v)| may be slightly less (respectively, slightly more) than

θr2. But on a surface, the area |A(x, r, θ, v)| may be slightly less (respectively, slightly more) than  θr2. In these cases we say that the surface has positive (respectively, negative) Ricci curvature at x in the direction v. More precisely, we have

θr2. In these cases we say that the surface has positive (respectively, negative) Ricci curvature at x in the direction v. More precisely, we have

Now it turns out that for surfaces, this more complicated notion of curvature is in fact equal to half the scalar curvature: Ric(x)(v, v) =  R(x). In particular, the direction v plays no role in Ricci curvature in two dimensions. However, it is possible to extend all of the above concepts to other dimensions. (For instance, to define scalar and Ricci curvature for three-dimensional manifolds, one would use balls and solid

R(x). In particular, the direction v plays no role in Ricci curvature in two dimensions. However, it is possible to extend all of the above concepts to other dimensions. (For instance, to define scalar and Ricci curvature for three-dimensional manifolds, one would use balls and solid

Now it turns out that for surfaces, this more complicated notion of curvature is in fact equal to half the scalar curvature: Ric (x) (v, v) =  R(x). In particular, the direction v plays no role in Ricci curvature in two dimensions. However, it is possible to extend all of the above concepts to other dimensions. (For instance, to define scalar and Ricci curvature for three-dimensional manifolds, one would use balls and solid sectors instead of disks and angular sectors, as well as making other necessary adjustments, such as replacing the expression πr2 with

R(x). In particular, the direction v plays no role in Ricci curvature in two dimensions. However, it is possible to extend all of the above concepts to other dimensions. (For instance, to define scalar and Ricci curvature for three-dimensional manifolds, one would use balls and solid sectors instead of disks and angular sectors, as well as making other necessary adjustments, such as replacing the expression πr2 with  πr3.) In higher dimensions it turns out that the Ricci curvature is more complicated than the scalar curvature. For instance, in three dimensions it is possible for a point x to have positive Ricci curvature in one direction but negative Ricci curvature in another; intuitively, this means that narrow sectors in the former direction “curve inward,” whereas narrow sectors in the latter direction “curve outward.”

πr3.) In higher dimensions it turns out that the Ricci curvature is more complicated than the scalar curvature. For instance, in three dimensions it is possible for a point x to have positive Ricci curvature in one direction but negative Ricci curvature in another; intuitively, this means that narrow sectors in the former direction “curve inward,” whereas narrow sectors in the latter direction “curve outward.”

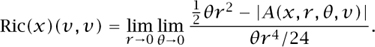

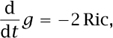

Now we can describe Ricci flow informally as the process of stretching the metric g in directions of negative Ricci curvature, and contracting the metric in directions of positive Ricci curvature. The stronger the curvature, the faster the stretching or contracting of the metric. The concepts of stretching and contracting will not be defined formally here, but they increase or decrease the distance between points along these directions. By changing the notion of distance, one also affects the notions of angle and volume (though it turns out that Ricci flow in two dimensions is conformal, which means that the notion of angle remains unaffected by the flow; this fact is closely related to the previously mentioned fact that in two dimensions the Ricci curvature is the same in all directions). Ricci flow can be described succinctly and precisely by the equation

although we will not define here exactly what it means to differentiate the metric g with respect to the time variable t, or what it means for that derivative to equal the Ricci curvature multiplied by -2.

In principle, one could perform Ricci flow on a manifold for as long a period of time as one wished. In practice, however, it is possible (especially in the presence of positive curvature) for the Ricci flow to cause a manifold to develop singularities: points where it ceases to look like a manifold, and where the geometry may stop resembling Euclidean geometry even at very small scales. For example, if one starts with a perfectly round sphere and performs Ricci flow, what happens is that the sphere contracts at a steady rate until it becomes a point, which is no longer a two-dimensional manifold. In three dimensions, more complicated singularities are possible: for instance, one can have a neck pinch, in which a cylinder-like “neck” of the manifold shrinks under Ricci flow, until at one or more places along the neck, the cylinder has tapered down to a point. The types of possible singularity formations for three-dimensional Ricci flow were only classified completely in a recent and very important paper of Grigori Perelman.

Some years ago, Richard Hamilton made the fundamental observation that Ricci flow is an excellent tool for simplifying the structure of a manifold: generally speaking, it compresses all the positive-curvature parts of the manifold into nothingness, while expanding the negative-curvature parts of the manifold until they become very homogeneous, in the sense that the manifold begins to look much the same no matter which vantage point one selects inside it. Indeed, the flow seems to separate the manifold into extremely symmetric components. For instance, in two dimensions the Ricci flow always ends up endowing the manifold with a metric of constant curvature, which could be positive (as in the sphere), zero (as in the cylinder), or negative (as in hyperbolic space); the fact that such a constant-curvature metric can always be found is known as the UNIFORMIZATION THEOREM [V.34] and is of fundamental importance in the theory of surfaces. In higher dimensions, the Ricci flow can develop singularities before perfect symmetry is attained, but it turns out that it is possible to perform “surgeries” (see DIFFERENTIAL TOPOLOGY [IV.7 §§2.3, 2.4]) on the singularities that develop this way, so that the manifold becomes smooth again and one can restart the Ricci flow process. (The surgery may, however, change the topology of the manifold: for instance, it can convert a connected manifold into two disconnected pieces.) In three dimensions it has recently been shown by Perelman that Ricci flow, when augmented by surgery to remove the singularities, does indeed convert an arbitrary manifold (obeying some mild assumptions) into a finite union of some very symmetric and explicitly describable pieces; the precise statement of this conclusion was known as the geometrization conjecture of Thurston. One consequence of this conjecture, which is now a rigorous theorem proved by Perelman, is the POINCARÉ CONJECTURE [V.25]: any compact three-dimensional manifold that is simply connected (meaning that any closed loop on the manifold can be contracted smoothly to a point without ever leaving the manifold) can in fact be smoothly deformed into a 3-sphere (which is to four-dimensional Euclidean space as the usual two-dimensional sphere is to three-dimensional Euclidean space). The proof of Poincaré’s conjecture is one of the most impressive recent achievements of modern mathematics.