A Thames sailing barge; the detail shown includes the stem, anchor, stay fall tackle, windlass, bowsprit and bowsprit shrouds.

MODELLING THE BOATS

When it comes to modelling the boats on inland waterways, rivers and estuaries, basically they come in two categories: wide-beam craft and narrowboats.

WIDE-BEAM BOATS

Wide-beam boats, as the name suggests, are those built to a wide beam in order to carry more goods. These boats were to be found sailing and plying a trade on the navigable rivers and the larger canals, as well as coastal sea-going craft. The boats range from steam packets and sailing barges to the not-so-glamorous scrap-carrying barges and Tom Puddings.

KEELS AND SLOOPS

Of all the British inland waterway craft, there was probably no vessel more distinctive than the Humber sailing keel. These boats had a single mast with a square rig, which follows the traditions of our Norse and medieval ancestors. The keels had many variants, determined by the navigations on which the craft were employed. Some of the keels had to rely on horses or tugs to pull them and did not require any rigged sail, while others sailing the river estuaries, and those that made coastal passages, carried enough sail for the job in hand.

The original keels were built of wood, but later iron and steel keels were built right up to the 1930s. The majority of keels were owned by large carriers such as Furley & Bleasdale, operating from the Yorkshire side of the Humber.

The sloops had basically the same hull and like the keels had many variants, and were designed to sail the inland navigations. However, most were in fact restricted to the Humber estuary, with a rig that suited the river’s conditions. The main cargoes included sand and gravel from the Trent lowlands and chalk stone from Barton. From Lincolnshire they regularly carried building materials such as bricks, tiles and cement, while the smaller market boats carried vegetables from Barton to Hull.

Both these types of boat were heavily decorated with elaborate artwork. The hull colours were very distinctive, with blue and green being the most popular; however, yellow was the preferred colour of Farleys of Hull. The Trent Navigation favoured white, while red was the choice of John Hunt of Leeds. The later boats with steel keels did not have the elaborate decorative embellishments of their wooden counterparts, apart from the timber heads, rails and beadings, which were picked out in contrasting colours.

SHEFFIELD KEELS

The Sheffield keels were powered by sail, steam and motor. They worked both the Sheffield & South Yorkshire and the Sheffield canals, and were also common carriers on the Aire & Calder and the River Ouse. William Bleasedale was one of the major owners working boats out from Hull. These boats carried a blue and white colour scheme until they came under the control of British Waterways and were repainted in the familiar corporate colours of yellow and blue.

The owners of Swan Flour Mills in Hull employed six steam keels to work between Hull and Rotherham. These boats wore an overall green livery with the hawse plates painted in a diagonal red and white pattern. The funnel was white with a black cap, and it was hinged to negotiate the low bridges. The principal cargo carried by the Sheffield keels was coal, grain and of course from Sheffield, steel.

WEST YORKSHIRE KEELS

Also members of the keel family were the shorter Yorkshire keels, more commonly known as West Country boats. These boats would travel over the Pennines to the ports of Manchester and Liverpool. This type of boat was also employed on the Calder & Hebble navigation. Most of the fleet was painted in a yellow and black livery, though with additions of red, green and sometimes blue, making the latter similar to the British Waterways livery.

THE YORKSHIRE TANKERS

The two companies that played a major role in canal and river tanker operations were Whitaker and John Harkers. The main cargoes were creosote and petroleum, carried in drums until bulk liquid carriage started in the 1920s. The Whitaker barges were painted in a mainly red livery, while the John Harkers fleet adopted a blue colour scheme.

STOVER CANAL BOATS

Devon is not really noted for its canals, and the Stover Canal was only around 2 miles (3km) long. It was built to link the navigable part of the River Teign estuary with Teigngrace, where the trans-shipment point was originally established with the Haytor Granite Tramway. The barges were wide-beamed, and consisted of flat-bottomed wooden hulls. They were equipped with a single square-rig mainsail for use on the Teign estuary when the tide permitted passage. They mainly carried ball clay and granite, which would be trans-shipped on to larger ships at Teignmouth; they would return with loads of coal, timber and sand.

In appearance their hull was tarred black, with the gunwales picked out in white or green. The Great Western Railway took over the ownership of the Stover Canal, and in the later years of its existence the barges were pulled first by steam and then motor tug boats.

TAMAR KETCHES

The Tamar ketch was a shallow-bottomed boat with two or sometimes three masts. It was a small class built specifically to trade cargoes up and down the River Tamar on the Devon and Cornwall border; in particular it transported locally mined copper and tin ore to Aberdulas in South Wales for smelting. On the return journey the boats would be loaded with limestone or coal, to be broken and mixed together for burning in the lime kilns to produce quicklime. This would be used as a commercial fertilizer, to be spread on local fields to sweeten the acidic soil. Alternatively the coal was used to fire the boilers of the myriad steam engines that abounded around the mines.

The ketches normally required a crew of three; they would land on the (high) tide, when the crew would manually unload around 15 tons of ore. The coal or limestone carried on the return journey would again have to be manually loaded, and the ketch would set sail on the next but one tide. The return journey could be hazardous, having to battle the rough seas, especially around Land’s End and the Lizard Peninsula. This back-breaking exercise would be repeated again on arrival, and it was hardly surprising that physically these men were completely worn out by the time they reached the age of thirty. The ketches were often built at the small boatyards spread along the Tamar. One such ketch was the Gladstone, which today can be seen at Morwellham Quay Museum. She was built at Goss’s boatyard, which now stands under the Calstock viaduct. Goss’s was a typical small boatyard, and there is a model of it at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich.

The ketches usually lasted a long time in service, being largely in salt water, which preserved the timber hull. To counteract the fact that they spent half their life in fresh water, which would rot the timber, a characteristic feature of the ketch was that it carried boxes containing rock salt, fitted under the beam shelf. The decks would be regularly washed down with salty water and left overnight because the salt would pickle the wood; the heat of the sun the next day dried all the salt into the timber.

The names given to the ketches did not follow any pattern as such, with most being named after a member of the owner’s family, usually the daughter. Some of names listed at the Appledore Maritime Museum are Clare May, Garlandstone, Shamrock, Kathleen & May, Amazon, Emma Louise, Brazil, Two Sisters, Tamar, Atlantic and Flora May.

The rivers and broads of Norfolk demanded an adaptable craft. Originally square-rigged keels were used, but from the eighteenth century a gaffed wherry became the obvious choice. These vessels were easier to sail, and having a saucer-shaped hull were ideal for a shallower draught when loaded with cargo. The wherries survived, though in lower numbers, right through to the 1930s. The main shipping cargo for this part of the land was sugar beet and bricks for local building. One of the Norfolk wherries, Albion, survives today and has been fully restored, and a scale model of this craft is also on display in the collection at the Merseyside Maritime Museum in the Albert Dock, Liverpool.

The wherry’s colour scheme was fairly standard, with a black hull and black sail. The coamings above the hull were painted in blue and white bands, and all the hatch covers and boards in red. Blue, black and yellow beading was used on the cabin panels. The mastheads were heavily decorated, with bands of colour and usually a star painted around the halliard sleeve pin bearing. The name of the boat, together with the port of registry, was picked out on the panels at the front, flanking the mast.

THE THAMES AND MEADWAY SAILING BARGES

The Thames sailing barges were not totally inland craft, although they did use the navigable rivers and larger canals. They were built in large numbers and were synonymous with the Thames. Their elegant shape and full sail, together with their familiar bowsprit, made them a well loved craft. Thames sailing barges would often cross the North Sea using detachable leeboards, but their main routes involved carrying cargoes up and down the east coast. The owners would decorate the barges with elaborate scrollwork. The bulwarks were painted dark greens and blues, and the name of the barge and the port of registry were painted on to a scroll or garter background, positioned each side of the stern post.

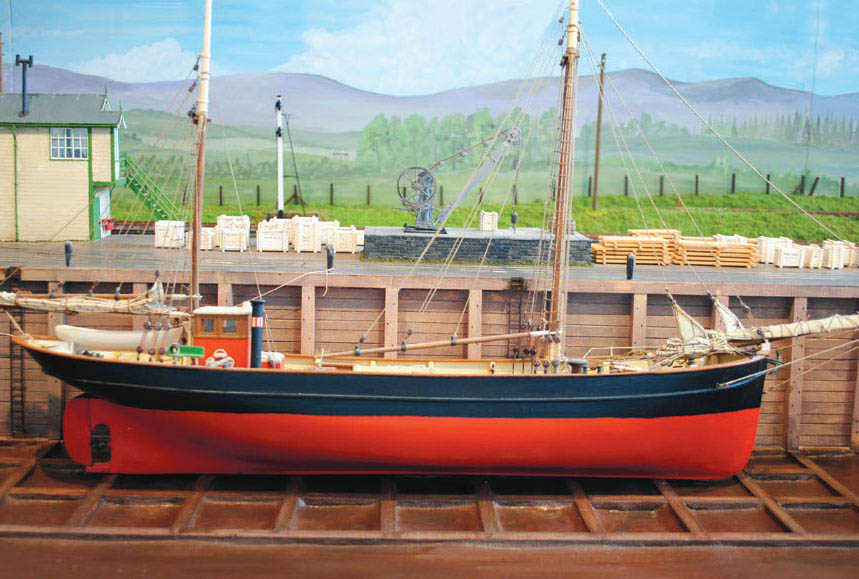

A Thames sailing barge; the detail shown includes the stem, anchor, stay fall tackle, windlass, bowsprit and bowsprit shrouds.

One of the bulk grain barges, alongside Chelmer River Quay at Maldon. In the background is one of the grain loading silos.

Looking along Chelmer River Quay, a number of vessels are moored, including the bulk grain barge, a floating dock, a sailing barge and a small coaster.

Another view looking along Chelmer River Quay at Maldon.

Two different designs of stern on the sailing barges Hydrogen and Thistle, both registered at London.

A few of these sailing barges remain; today Hydrogen, registered in London, is one such example of the preserved craft, and there are seven usually moored at Maldon’s Hythe Quay in Essex. These historic vessels are now used for leisure, offering sailing barge cruises, along with corporate hospitality including wedding receptions and birthday parties. One of the cruises includes a visit and history talk about the port of Ipswich and the Thames sailing barges on the River Orwell. Therefore the barges now bring in a very different kind of income from the freight cargoes they were originally built for.

The sailing barge George Sweed moored at Hythe Quay, Maldon.

A small ketch grounded on the Blackwater estuary mud.

Albert Dock in Liverpool is now home to many historic boats.

The River Severn was well known for its various craft, but the most common were the Severn ‘trows’. A group of these vessels picked up the name of ‘Wich barges’. The wooden-hulled, single-masted craft were limited in length, because of having to negotiate the locks on the Droitwich Canal further up the river. The canal was extended to link with the Worcester & Birmingham in the mid-nineteenth century. Salt was the main cargo for the boats in one direction, while coal from South Wales and the Forest of Dean was brought back on the return journey.

The barge hull was painted black, with red along the gunnels, and the masthead was picked out in bands of red and white. The boat’s name and the port of registry were written on each side of the stern post. The Wich barge Harriet still survives, though it is marooned on the banks of the Severn at Purton.

DUCKERS

The name ‘duckers’ was given to the craft operating along the Bridgewater Canal. They were a type of craft known as ‘flats’, and were owned by the third Duke of Bridgewater, before being operated by the Bridgewater Department of the Manchester Ship Canal Company. Before steam-tug towage was introduced, these vessels would have to hoist sail along the River Mersey. After World War II the wooden-hulled duckers were replaced with more modern steel-hulled craft; they were also given diesel engines, and were employed carrying imported grain to the Kellogg’s factory at Trafford Park, Manchester.

The teak wheelhouse of the Kathleen and May. The schooner has been restored to her original condition.

The bowsprit belonging to the schooner Kathleen and May.

Another fine restored vintage yacht moored in Albert Dock.

The Gloucester docks are also now home to historic marine and river craft.

The livery was a black-painted hull with red and green above, with yellow lettering. The later steelhulled craft were given a green and yellow livery. One of these barges is preserved at the Ellesmere Port Boat Museum.

WEAVER PACKETS

The Weaver packets were introduced on the River Weaver by the Winsford salt producers, H. E. Falk. First, the steam vessels were designed to tow an unpowered barge laden with salt to Liverpool or Birkenhead. The salt would be trans-shipped at the docks for export worldwide. More steam packets were built capable of towing up to three fully laden dumb barges. The packets started life as sailing vessels and were originally built with wooden hulls. They remained in service until the mid-1930s. The Vale Royal was built in 1875 and converted to steam power in 1883, and was not withdrawn from service until 1953, although by then she was used as a steam lighter on the Mersey.

The Weaver steam packets followed the tradition of the sailing flats, with bands of colour to the masthead. W. J. Yarwood & Sons continued to build Weaver packets for Bunner Mond and their successors ICI until 1947; these comprised four steamers and five as motor vessels, with Crossley diesel engines. The last packet to be built, Wicham, is now at the Merseyside Maritime Museum, where she has been fully restored.

ROCHDALE BOATS

The Rochdale Canal was possibly the busiest of the trans-Pennine routes. The Rochdale boats consisted of both keels and flats; the keels were built in the West Riding and the flats were built in the yards of Rathbones & Muggs of Stretford. The hulls were made completely of wood up until the last eighteen, which had steel frames to carry the wood planking. These vessels were built between 1906 and 1914. Both keels and flats required horses to pull them along, although steam packets and tugs took over the towing duties along the Mersey and the Manchester Ship Canal.

The Rochdale boats’ livery was a black-tarred hull with red, white and blue above, though white was the prominent colour and the red and blue were used for embellishments; the boat name and company name were cut into the stern rails, painted in black letters.

PUFFERS

The Puffers were synonymous with the River Clyde and gained the name of Clyde puffers, although the vessels were also common on other rivers and canals. The puffer was also, of course, a coaster because of its sea-going capabilities. Although puffers were associated with Scotland, they did venture south to Tyneside and Middlesbrough. Hays were owners of the biggest fleet on the River Clyde; this totalled nearly one hundred vessels, of which most remained in service under steam power well into the 1960s. The vessels that were converted to diesel power lasted another ten years. The early puffers were equipped with a sail. The name originated from the sound given by the non-condensing steam engine, which carried through to the later diesel-powered boats.

Langley Models produce a very good kit in resin and white metal of a Clyde puffer, along with a few other boats in 1/76th 4mm scale.

I hope I have covered an interesting selection of wide-beam craft for you to consider for your model railway and diorama requirements. Nevertheless, there are many other wide-beam craft that I have not mentioned here, and I would suggest you seek out further reference books that specialize in such vessels. Alternatively, trips out to visit the inland waterway and the many maritime museums would be worth considering.

MODELS OF WIDE-BEAM BOATS

There are kits available of a few of the boats I have listed from specialist model boat suppliers, however they do not always match up to the standard scales of our model railways. I would suggest looking through the catalogues or lists on the internet to see just what is available, and what would suit your particular requirements.

If the type of craft is not available in kit form, then you will have to scratch build it. This can be an overwhelming task, and it requires special skills and knowledge of the craft to obtain realistic results. It would be worth trying to obtain some scale drawings and photographs of the craft, if these are available, before you start. This aside, attempting to build a model boat could be very rewarding, giving you the opportunity to try your hand at something completely different to modelling railways.

SCRATCH BUILDING THE Sylvia May

I have included here a guide to scratch building the Tamar ketch Sylvia May, by Chris Peacock.

The model was based round a block of balsa wood, first made to size by gluing smaller blocks together with PVA glue, then shaped with an orbital sander. The mast positions were located, and two 6mm holes drilled to accommodate them; this was done on the pillar drill to ensure that the holes were vertical. These two holes then became the datum for the rest of the boat building.

Next, a template was fixed over the holes with the deck shape drawn out. The template was then used continuously to ensure that both sides were the same shape while using the sander. Once the desired shape had been achieved, the hull was painted black using poster paint. The template was then used to form the deck, which was marked up using a fine marker pen to represent the planking. The decking was given a wash of ochre paint before being glued to the hull, using the holes as fixing points.

Using the vertical shape of the deck as a marker, the two bulwarks were next shaped and cut from 1mm card and glued to the decking. PVA glue was used throughout the construction process, usually applied with a small paintbrush. 2mm pine was used to represent the stanchions, first cut to size before being glued into position to the inner bulwarks. Finally the top rail, made from 4 × 2mm pine that had already been steamed to shape, was glued on top. It is important to realize that problems could easily occur due to the many curves in the design, as the deck is not flat in any direction, simply to allow the water to run off easily.

The masts, jib and bowsprit, and other pieces of mast work, were made from either 6mm or 4mm dowel rods. These were placed into the lathe, although a power drill can also be used to create a slight taper to the lengths of rod. This was achieved by using a fine sandpaper: the tapering produced is not a lot, but it is definitely apparent. Various pieces of additional woodwork were cut from the 2mm pine and attached, again using PVA glue. The gearing to operate the jib was all made with small locomotive gears; these were first soldered together, before being fixed into position. Epoxy resin or Superglue can be used to secure the metal parts to the wood.

The main guy ropes holding the mast in place were made from four strands of wire using a length of 7/0.2 layout wire. This was completely stripped, then four strands were selected and twisted to produce the hawsers. Pins were soldered to the tensioned wire, which had first been placed into the mast. Various suppliers such as Hobbys sell items aimed directly at the model boat builder, such as pulleys, ropes, chain, bells and anchors, and all the other ropework for the model was made from these sources.

When any rope is being threaded through a pulley, it is well worth clearing the hole with a small drill first. For this model, when the rope was at the desired tension, a small blob of PVA was introduced at the point where the rope exited the pulley; it was then allowed to dry. This method ensured that all the rigging remained as it should, without any twisting or snagging, but it does mean there is no way of pulling or lowering the sails into position. However, on a model such as this, moored up against the quayside, the sails would be in the lowered position anyway, so there is no need to change things.

The sails themselves were made from a thin cotton material, bought especially for this task and obtainable from material suppliers found on the market or along the high street. The material was first coloured to a buff shade by soaking it in cold tea. To cut the sails to the correct shape, a paper template was made first, then fixed to the material, which was cut around it. Once cut out the sails were rolled up and tied to the relevant jib. Making templates first and then rolling the material up in this way might seem a waste of time, but it will ensure that only the correct amount of material will be used, which will produce a believable-looking result.

To produce the wheelhouse, 2mm plywood was used, with the doors scribed in to represent planking. Small holes were then drilled for the portholes. The ship’s wheel was procured from Hobbys, and was fixed to a shaft running into the wheelhouse. A piece of timber was shaped and attached to the roof of the wheelhouse as the cradle for the jib to rest against when the sails were lowered.

All that was now left to do was to provide the various winches and dollies, together with the anchors. After referring to photographs at the Appledore Maritime Museum, these details were made up from a mixture of brass, wood and plastic, and components from model boat suppliers.

During the construction process, parts and sections of the boat were painted and varnished. It was felt that this might be an impossible task to do once the model was complete, as trying to paint into all the corners would be very difficult. However, this also meant that whilst carrying out the later work, clean hands and care were needed so as to avoid damaging any of the earlier work.

The painting consisted of only four main colours: black for the hull and the inside of the hold, ochre for the decking and the masts, grey for the bulwarks and finally white for the top rails.

To ensure that all the colours used remained constant throughout the building process, the paint was made up in a large enough batch to last throughout. The paint media used on the model were both acrylic and poster paints.

The name of the ketch is the name of a good friend, which fitted with the traditions of these craft: Sylvia May.

NARROWBOATS

Let us now take look at some of the vessels built to navigate our inland canals with narrow locks. The narrowboats were built with a beam of around 6ft (2m), hence the name ‘narrowboat’. The early boats were all towed by horses; later, a few narrowboats were built with steam-powered engines, though the majority of the later boats had diesel engines. These were known as ‘motors’, and for a greater load-carrying capacity, the ‘motor’ was paired with a non-powered boat called a ‘butty’. This arrangement became common practice right up to the end of commercial carrying on our inland waterway system. From the many narrowboats built, I have presented a selection of the best known to consider for a model. However, before we look at this selection, it is worth mentioning the ‘flyboats’.

This was the name given to the boats that carried high value goods and perishables, and provided a non-stop express service. Flyboating was introduced in the late eighteenth century for both broad-beam and narrowboats. The flyboats were given priority at the locks, and were allowed to overtake other craft and to pass through locks at night. For recognition of priority a symbol was given to the boats, usually in the form of a large red diamond on the cabin side. This fast service required the employment of double crews to keep the boats going day and night. The large carrying company Fellows, Morton & Clayton introduced steam flyboats for the London, Braunston, Birmingham, Leicester, Nottingham and Derby services.

The rear of the boat cabin of the Fellows, Morton & Clayton butty boat Kildare, showing the decorated doors and interior dressings.

The front end of three Fellows, Morton & Clayton boats. Note the forecabin on Kildare.

FELLOWS, MORTON & CLAYTON LTD (JOSHERS)

It would be fair to say that Fellows, Morton & Clayton Ltd were the best known of all the many canal-carrying fleets. The company had both the largest number of boats and range of operations, together with its own warehousing. James Fellows introduced company boats as early as 1837. By 1860 the prospering company was also run by James’s son Joshua, from whom the boats picked up the nickname of ‘Joshers’. During the 1870s Fredrick Morton joined the partnership, and in 1889 the company amalgamated with the well established firm of Thomas Clayton.

The extensive fleet included three of the first steam-powered narrowboats. President can be seen today fully restored, and making appearances at the vintage boat rallies. She is kept along with her butty boat Kildare at The Black Country Living Museum.

The FM & C butties totalled around two hundred at the peak of operations. Most of the boats were constructed of wood, although some had hulls of both wood and iron. Fellows, Morton & Clayton built the majority of the boats themselves at Saltley, Birmingham and Uxbridge. A good number of the butties feature a forecabin, and the preserved Kildare has a good example of this feature; the lowprofiled cabin gave accommodation for boat families’ children to sleep side by side.

Rear view of the same three Fellows, Morton & Clayton boats. Note the cabin door decoration and how the boats are roped together.

A closer image of the forecabin of Kildare: this provided the sleeping accommodation for the boat family’s children.

The signwritten cabin side panel of a Fellows, Morton & Clayton boat. Note the colour scheme is of the later red, green and yellow colours adopted by the company. Also worthy of note is the black panel carrying the boat’s place and number of registration.

The company livery in the early days was predominately black and white, with bright red for all the beading and trims and the cabin tops. From the mid-1920s the company adopted a red and green livery with the beading and trims picked out in yellow. The steamers, however, still carried the black and white livery to the end of service. The early style for lettering was white with a light blue drop shadow, with unshaded black lettering on the white panels. The later livery still used white lettering, but this was shaded yellow with green flashes added.

SAMUEL BARLOW COAL CARRIERS

The well known carrier for coal on the canal network was Samuel Barlow. The fleet was based at Tamworth in Staffordshire and at Birmingham, and transported most of London’s coal via the Grand Junction, now the Grand Union Canal to the capital. The coal was extracted from the pits around Coventry, Bedworth, Nuneaton and Tamworth. By 1944 the company had a fleet of seventy long-distance boats, besides the local day boats.

The grandson of Samuel, Edwin Barlow, started a separate carrying and coal merchant business, and the cabin sides of his boats had the lettering ‘S. E. Barlow Canal Carriers’. These boats were eventually taken over by the Samuel Barlow Company in 1957. The fleet of boats were still in regular service into the 1960s.

The decorative cabin side panel of a Samuel Barlow coal-carrying butty. Note the dark green background colour, framed with a painted wood-grained effect. This elaborate colour scheme remained until the end of commercial carrying on the canal system.

The decoration added to the rudder of butty boat Ilford. Also note the decoration to the tiller arm, which is reversed in its mounting when not in use.

The livery was predominantly a dark green edged on the cabin with a painted wood-grain effect; the beading separating this from the green was yellow. The cabin tops and trims were bright red, along with a red-painted stern and rudder post on the horse boats and butties. The lettering on the cabins was signwritten with white letters shaded with red, while all the boats sported a rose design added to the top corners of the green cabin panels. The non-motors including a rear panel painted with traditional castle artwork.

For those readers interested in both the Samuel Barlow fleet and canal life, I would recommend finding a copy of A Canal People, which presents a portfolio of photographs of Robert Longden. The collection depicts both the families and the working environment of our canals, making it a perfect reference for any modellers trying to capture this way of life on their model railway or diorama.

GRAND UNION CANAL CARRIERS

This carrier came about as an attempt to create a modern commercial system after the amalgamation of the canals from both London and Birmingham and those serving the Derby and Nottingham coalfields. The original fleet of 370 wooden and iron boats was gradually replaced as newer ones arrived. The company ordered various types, although the main classes were the ‘Stars’ and the ‘Towns’, these being delivered between 1934 and 1938; some of these boats were built by shipbuilders Harland & Wolff of Belfast.

The bright colour scheme given to the boats of the Grand Union Canal Carrying Company. Note again the decoration of roses and castles added to the door panels.

The livery for the earlier boats was dark blue on the cabin sides, edged with light blue. The lettering was unshaded white, although the fleet number appears in red with a white outline to the numerals. The beading and trims were also picked out in white, with the cabin tops retaining the dark blue.

Later the livery changed to a bright red for the centre of the cabin panels, edged with the corporate dark blue. The lettering was signwritten in white again, although this had a drop shadow included in the dark blue colour. The fleet numbers were changed to blue, with the white outline retained. The lettering was also changed during the austerity years of the war, when the name that appeared in full on the cabin sides was replaced by the simple initials of G.U.C.C. CO. Ltd. This livery of a more austere decoration remained well into nationalization.

THE POTTERIES BOATS

The best known company for carrying the raw materials used in the pottery trade was Potter & Sons of Runcorn. The boats would carry clay, flint and feldspar in one direction, and return with loads of coal and crated pots in the other. All the original company boats were constructed of wood, and would have been towed by horse. The company only acquired a few motors secondhand in the late 1940s, with the last of the Potter boats trading up until 1958.

The boats had a livery similar to that of Samuel Barlow, with a dark green cabin colour edged with a frame of painted wood graining, with yellow beading. The back panel was decorated with the characteristic design of roses and castles. This type of decoration was very popular with boatmen on the Trent & Mersey Canal, and was known as ‘knobstick’ style. The forward panel was a plain black, with the registration town and number lettered in plain white. The cabin lettering was white with a yellow drop shadow shaded red in the corners.

All the boat names for the fleet began with the letter ‘S’, some after birds such as Seagull for example, while another series began with ‘sun’, for example Sunlight. The boat names appeared in white letters on a red background, this time shaded light blue; the red was extended under the stern. The cabin tops were mainly red, although a lighter green was used in places, including the band on the top of the rudder. For all the elaborate decoration applied, the stove chimneys remained plain black without any brass rings.

THE SEVERN CANAL CARRIERS

The Severn & Canal Carrying Company resulted from a merger with competitor J. Fellows of Fellows, Morton & Clayton. One of the company’s main customers was Cadbury’s of Bournville, although Cadbury’s did have their own fleet of boats. After 1928 Cadbury’s gave up their boat fleet and used other carriers, most notably the Severn & Canal Carrying Company. New, welded wroughtiron motors were ordered from the shipbuilders Charles Hill, of Bristol. This new series of boats was called the ‘Severners’, and was one of the longest seen on our canal system.

The livery was kept simple, with royal blue being the main colour for the cabin sides, edged with plain white. All the lettering was white sans serif without any drop shadow used; however, there was an exception to this: the company used the large cabin sides of the motors to advertise their services, and the company name was also displayed in a curved banner with a serif style of lettering adopted, this time with the initial letters larger than the others. The top corners of the cabin sides were filled with a white scroll design. All the funnels and stove chimneys were plain black with no brass embellishments.

THE RAILWAY COMPANY BOATS

As the railways took over ownership of most of the canal navigations, they also had their own fleets of boats, though a good number of the railway-owned craft were employed for maintenance work rather than cargo-carrying duties. The Great Western had ten boats, and the London, Midland & Scottish had sixteen, with thirteen inherited from the London & North Western and the Midland Railway. The London & North Eastern also had a number of boats, although these were all used for maintaining the navigations.

The liveries of the railway boats were kept very simple. The Great Western adopted a cream and black colour scheme, with cream the predominant colour. The centre of the cabin panel had the initials ‘G. W. R.’ painted in black. The fleet number was also painted black, appearing in the centre of the rear panel. Sans serif letters and numbers were used, although the boat name was more ornate, with block serif letters painted black with a red drop shadow.

The London, Midland & Scottish used a mid-grey as the predominant colour for the cabin side. This was framed with a white border, with red-painted beading and trims. The initials ‘L.M.S.’ were larger than those on the Great Western boats. The lettering was in Clarendon-type face, which was used for the corporate identity for the railway. The letters were white with a black drop shadow, making the letters stand off the neutral grey background.

The fleet numbers appeared in the centre of the rear cabin panel, painted black, with a mid-grey drop shadow used, because this panel was painted plain white. The boat-name panel was also white, with the name of the boat appearing in the same style of Clarendon lettering as the cabin sides, but this time in black with no drop shadow.

DREDGERS AND ICE BREAKERS

Other maintenance boats included the spoon dredgers and the ice breakers. These were both vital vessels, employed to keep a clear passage along the inland waterway navigations.

NARROW-BEAM TUG BOATS

The narrow canals employed a number of tug boats; originally these would have been steam powered, but craft that were built later and rebuilt craft were powered by diesel engines. These tugs were much shorter in length, since they did not require any hold space for carrying cargo. Their main duty was to tow long trains of unpowered barges to maximize load capacity; others were used for towing assistance through the long tunnels on the navigation, while some were employed for the ever-growing tasks of canal maintenance work.

The liveries for the tug boats varied, although for the most part they were kept very simple and did not receive any of the elaborate decorations given to the narrowboats.

The canals, just like the railways, were nationalized under the Transport Act 1947 on 1 January 1948. This resulted in a good number of the cargo-carrying fleets owned by navigation authorities being brought together under the body of the Docks & Inland Waterways Executive of the British Transport Commission, which resulted in the birth of British Waterways. The majority of the boats came from the Grand Union Carrying Company, the Severn & Canal Carrying Company, and by 1949 boats also came from Fellows, Morton & Clayton.

A new nationalized corporate colour scheme was needed to identify these boats, and yellow and blue was chosen. The early livery favoured yellow as the predominant colour, edged with a deep blue. Later, however, this was reversed and blue became the predominant colour. The styling was kept simple, and a sans serif typeface was used with a drop shadow. The lettering for ‘British Waterways’ appeared on a gentle curve, with the fleet number or boat’s name positioned centrally in a straight line directly underneath. The lettering was painted in the yellow with a black drop shadow on the latter livery, and blue with a black drop shadow on the early yellow-painted cabin panels.

The later livery also included a new transferred logo, usually in the centre of the back cabin panel. The river class of boat introduced in the later years included a porthole in this position, so the logo on these boats appeared just to one side.

Although the livery to the outside was kept simple, the boats retained the traditional decorative embellishments to the inside. The cabin doors and some of the cabin interior fittings received the roses and castles decoration.

BLUE LINE CARRIERS

The final fleet of narrowboats included here came into existence from a hire fleet called Blue Line Cruisers based at Braunston. From this hire fleet, a new fleet of cargo-carrying boats known as ‘Blue Line Carriers’ was born; although only consisting of a few boats, they existed as an independent carrying organization. However, the contracts soon ran out due to competition from the railways, and also by this time the roads, and the last commercial runs were made in October 1970. One of the last carrying boats was the butty Raymond, which was paired with the motor Roger. Raymond has now been completely restored and can be seen at most of the boat rallies and gatherings.

The front end of three British Waterways’ boats. Braunston church steeple is visible in the background. The graveyard here contains many graves of working boat families.

The rear of the three British Waterways boats in their distinctive blue and yellow livery. Note again the out-ofuse position of the tiller arm of butty Bordesley.

The livery consisted of a blue centre cabin panel, with the name of the company and the Braunston telephone number all appearing in white block serif lettering with a black drop shadow. The company logo was also included: a distinctive large ship’s wheel positioned at the front of the cabin side panel, again painted in white.

The cabin side panels were edged with a painted wood-grain effect, with a yellow trim separating this from the blue panel. The cabin tops were bright red with green trims on the hatch sides. The butties such as Raymond had more decoration added, with the name panel on the stern painted red, and the boat’s name lettered in white with a blue drop shadow. The name panel also included a compass roundel, together with a diamond freeze situated under the first quarter of the cabin. The rudder post was also highly decorated, with another compass roundel appearing in the centre. The stern was painted red, with a collection of roses painted directly under the name panel. The butty would also include a rear cabin panel decorated with a traditional castle. The cabins of these butty boats featured a porthole positioned just off the centre, and to accommodate this, the company name had to be split.

The boats lasted in operation until the 1970s, and would make an attractive addition to any model based in this period.

There are many more narrowboats and carriers that I have not covered here. As always, if modelling a particular location and period in time, I would advise researching these to keep your model as authentic as possible.

The livery given to the boats of the Grand Union Canal Carrying Company, with dark and light blue being the predominant colours.

Fellows, Morton & Clayton butty Kildare moored up at Braunston.

One of the later built, 70ft (21m) long Grand Union Canal Carrying Company boats waiting to go through Dallow Lock on the Trent & Mersey Canal. Note the simplified livery, using just the initials G. U. C. C. Co. Ltd. in cream on a red-painted cabin. Also worthy of note is the addition of the portholes to the cabin sides, these being common on narrowboats that were built later.

The front end of the same motor; in this view the extra-long length is evident, together with the sheeting over the cargo hold.

One of the standard iron-hulled carrying barges. Note the lack of any cabin provided for the boatmen. Barges such as these were towed by horses, or later tugs, and carried loads of coal, limestone or scrap iron. They were a common sight in the Black Country, sometimes seen in long trains roped together. This example was photographed moored alongside the lime kilns at the Black Country Living Museum.

Another type of maintenance boat required to clear the navigation in the depths of the winter months. The boat pictured is the ice breaker Ross, built in 1847 for the Birmingham Canal Navigations Company (the BCN). It is now the only one left of the BCN ice boats, and is the oldest working narrowboat on British canals. It was horse drawn, and was employed for clearing sections of canal between the mines of Cannock Chase and the power stations around Walsall and Wolverhampton.

One of the railway maintenance boats at the Black Country Living Museum. Note the lack of decoration on this boat belonging to the Great Western Railway.

This short narrowboat is the towing tug Coventry.

One maintenance boat that was required on a regular basis was the spoon dredger. This sample has an original riveted iron hull. She was built at the Birmingham Canal Navigations Company workshops at Oker Hill, Tipton, in 1875. She was sold by British Waterways for private ownership, and was rebuilt in 2005–2009 to her original condition; she is now a working display vessel at the Black Country Living Museum.

Probably the feature that everyone associates with the fleets of narrowboats is the very elaborate painting. A good amount of the painting was functional, such as displaying the company name on the sides of the cabin, but much more was simply for decoration, and the type of artistry became commonly known as ‘roses and castles’. The decorated boats did not start to appear until the boatmen brought their families to live aboard. Besides the decorative paintwork the boatmen’s wives would display their bric-a-brac collected over the years.

There has always been a theory that the decoration evolved from the gypsies, though there is little proof that this was ever the case. Nevertheless, the style and choice of decoration of a gypsy caravan is very similar to the narrowboat, and this resulted in the boatmen’s families being referred to as ‘water gypsies’.

Flowers, and especially roses, have formed a decorative feature on pottery for many years, and it is therefore highly possible that the original roses and castles were painted by artists who would normally be associated with painting ceramics and clock faces. The same style would then be adopted by the boatyard painters. The inclusion of the castles must have come later as an addition to a painted landscape.

As the amount of boat painting grew, it became apparent that a house style was necessary so the boats could be painted more quickly, so the artwork became much more stylized. This did not, however, detract in any way from the quality that could only be produced by such skilful painters.

The castles were always painted on to a white background, with the blue sky and clouds added first.

Next the water was painted, a lake or a river being the usual choice. The background colours were then added, along with the castles. Lastly, any trees would be painted if they were included in the composition. Some of the painters added swans or sailboats on the lakes, although the main contents varied little. The roses were painted in groups, with the leaves painted first. Each rose would start with a coloured disc, and the petals would be added one by one using a single stroke of the brush. Finally, details such as the veins to the leaves and stems were painted in using a fine brush. It was not only roses that were painted; many boat painters used pansies and daises to fill in the panels.

Looking across the boatyard basin at the Black Country Living Museum. A good number of narrowboats are present, including Fellows, Morton & Clayton steamer President, the ice breaker Ross and W. H. Cowburn’s motor Swallow.

Most of this type of artwork was painted on the cabin door panels and on a panel alongside the main signwritten cabin side panels, but the roses and castles did spill over on to the cabin furniture and items such as the water cans.

More formal decoration was applied to the narrowboats – for instance the cabin backs and fronts were painted with scroll-type designs. The boat owners would have their own distinctive designs, which would identify them on the canal, and which were also applied to the hatch or cabin slides, the latter being fixed over the cabin entrance. These were also painted in various designs, which might consist of a playing card suit as a centre piece, with a scrolled frame of a contrasting colour.

The tiller and ram’s head of the motors were also highly decorated; again these designs identified the boat owners, becoming an elaborate corporate livery. The tillers of the horse and butty boats consisted of eight-sided curved lengths of timber, and were painted in contrasting bands of colour on each side along their length. On other boats the tiller would be divided into vertical bands of colour. The tillers on the motor-powered narrowboats were much simpler, with tubular metal being used rather than wood. This was bent to form a ‘Z’ shape, with the ram’s head running down to the rudder painted either in bands of colour, or in a narrow angled, twisted design resembling a barber’s pole.

The empty hulls of barges moored alongside the lime kilns. Note that this is a separate arm of the canal to serve the kilns.

The top of the rudder post on the horse and butty boats was again decorated with elaborate designs. Bands of colour might be used, with the head picked out in red, blue or black. The sides of the rudder post might be painted with more roses, along with a compass roundel resembling a kaleidoscope pattern. The Trent & Mersey boats favoured a pair of red-painted, elongated hearts positioned back to back on a white background.

Besides the painted decoration, the tillers and the ram’s head would also have elaborate ropework; this type of design was almost certainly the work of the boatman’s wife.

Moving on to the stands and the box masts, these would also be painted, the designs varying depending on the owner: some used solid colour with chamfered edges picked out in a contrasting colour, while others preferred geometrical designs of different coloured diamonds or triangles.

Moving further forwards to the front, the cratch often supported artwork, with the centre sometimes repeating the mast and stands. The triangular sides would also be decorated, again usually with the familiar roses. Other boats had a more simple design applied to the cratch; for example, the Ovaltine boats using this space to advertise their product, with the slogan ‘Drink Delicious Ovaltine for Health’.

A few narrowboats featured a forecabin, a space usually reserved to accommodate the boat families’ children. The cabin would display the name of the boat, signwritten on the side panel and repeating the colour scheme of the main cabin sides. The fore end would again be decorated with geometrical designs or with elongated heart shapes, and the compass or solid roundels might also make an appearance.

Moving to the stern of the narrowboat, the counter of the motor would have bands of horizontal colour, most commonly red and white. The stern of the butty would sport the boat’s name, signwritten to fill the panel space, so the characters would start or end large depending on which side was in view. The letters would be white or yellow on a bright-coloured background of red, blue, green or black; occasionally black letters were used on a white or yellow background. The name panel was edged with a contrasting colour, with either a compass or solid roundel often used. A frieze of diamond patterns would extend along under the cabin sides. The elongated heart pattern could also be seen on some boats joining the name panel to the gunnels.

The boards, funnels, stove chimneys and the cabin tops in most cases did not receive any elaborate paintwork. The boards and cabin tops were painted red or with red oxide, although some narrowboats may have received other basic colours. The funnels and stove chimneys were always painted black, with a number of brass bands appearing near to the top. The steamers and some motors used black only, without any decorative brass bands. The stove chimneys were fitted with a brass garland that hung down the rear and was purely for decoration.

DECORATING MODEL NARROWBOATS

On a model narrowboat, especially those in the smaller scales, trying to hand paint such elaborate decoration would be very difficult, and a suggestion of the paintwork might be a better solution rather than trying to painstakingly paint in every last detail. The signwriting might also be an issue, and an alternative might be to originate the cabin side panels on a computer, using relevant graphics software.

Langley Models include sets of pre-printed side panels and stern name panels, plus some decorated panels and stands. All these can be carefully cut out and glued into position; however, you will be restricted to only what is available in the range.

Over the last fifty years or so there has been a boom in the private ownership of pleasure craft using our rivers and canal systems. This all started around the 1930s, with the upper classes wanting to spend their leisure time ‘messing about on the river’. At this time the boating leisure activities of these few were restricted to the rivers and estuaries and the Norfolk Broads, as the canals were still a going concern for commercial goods traffic and were not suitable or attractive at the time.

After World War II, however, the canals were being run down and were even less attractive, becoming overgrown, polluted and in a state of disrepair. Then in the late 1950s Tom Roult decided to do something about the state of the canal system. He converted an old narrowboat into a pleasure craft by adding extra accommodation; the boat was named Cressey. His task was to try and navigate some of the most run-down canals in the country to prove that they could still be used for leisure activities.

This started a campaign with like-minded canal enthusiasts, who took it upon themselves to clear the debris- and weed-choked canals. All this was done without the consent of the authorities, who tried to block them at every opportunity. Nevertheless, boat rallies were organized by the newly formed Inland Waterways Association, and these were very popular. They attracted visiting boats, which at this time were mainly small cruisers. And the events became a major success, gaining public support and exposure through the media.

This was extended throughout the following decades, with both privately owned boats and fleets of holiday boats all making an appearance. The canals were now seen to be an attractive way of spending leisure time and holidays for a good number of people, and furthermore this was now not the reserve of the upper classes, as the middle and working classes could afford their own boats, or families could treat themselves to a holiday on a hire boat. The canals were now cleaner, and wildlife began to establish itself along their banks even in the towns and cities.

Today, this leisure industry has become a massive concern, turning over millions of pounds every year. Large boating marinas have been established or built up along the canals, and the formerly old, dirty wharves have now become new developments for homes and leisure pursuits. Gas Street Basin and Brindley Place in Birmingham have become the city’s most desirable area, with a host of arts’ activities held alongside classy eating and drinking establishments, all fronting on to the canals. The canals have now become busier in the summer months than when they were carrying goods.

The majority of the leisure boats now seen on the canals are narrowboats. These use the same basic hull as on the commercial goods-carrying boats, however where the commercial boats would have given most of the space to carry cargoes, this is now used for accommodation. So although the narrowboats still look traditional from the outside, the insides have been transformed to provide all the modern luxuries that people have now come to expect.

MODELS OF LEISURE CRAFT

If modelling the inland waterways from the 1930s up until the present day, a leisure boat on a river or modern-day canal scene will not look out of place. There are a few kits in the railway scales available, most of these produced in resin, especially when it comes to the hulls. Langley Models comes to mind, with a 52ft (16m) holiday boat and a small river cruiser available in their range. Other craft could be scratch built maybe using balsa wood for the hulls.

COASTAL AND OCEAN-GOING VESSELS

There are far too many craft that fit into this category, so for this book I will concentrate on the smaller vessels that would fit into a model of a port or coastal harbour. I will start with the fishing boats that spent all their existence fishing the seas around our coast. Fishing boats have been around for hundreds of years, once man found that the seas provided a bounty of food to be harvested.

The earliest fishing boats I would like to cover in this book would be the luggers. This small craft was synonymous with the Cornish coast, where at certain times in the year they would be employed in bringing in the pilchard harvest. This was one of Cornwall’s major industries, and coastal towns such as St Ives grew on this trade. The luggers had two masts, both with a square-rigged sail, and they also feature a ‘stern sprit’ to hold the rear sail.

BRIXHAM TRAWLERS

Brixham was once the home of the world’s largest fleet of wooden-hulled sailing trawlers, and it was in Brixham that the method of beam trawling was developed. Between the late 1880s and the late 1920s over 300 trawlers were built, most of them in the shipyards of Brixham. Today only six of these graceful-looking craft remain, all belonging to the Brixham heritage fleet.

The trawlers carried a gaff rig, which enables fore and aft sails to be set, four-sided rather than triangular. The boats were between 60 and 80ft (18 and 24m) in length, with a long straight keel. The trawlers were famous for their red sails, which were coated with red ochre to give that distinctive appearance.

DRIFTERS

The other type of fishing boat was the drifter, so called because they fished by using a drift net, rather than the trawl net, which was dragged along the sea bed. Most drifters fished for herring, and became known as ‘herring drifters’. The boats were originally all sail rigged, with steam and diesel power taking over, although the boats were assisted by a mizzen sail. This was used to steady the boats when the nets were put out. The drifter fishing boat was common to most of the fishing harbours around the coast of Britain.

COASTERS

The coaster was a small trading vessel that carried cargoes around the coast of Britain. They did, however, cross the Channel to take trade to the ports of Holland, France and Belgium, while some ventured even further afield. The coaster would carry various general cargoes including timber and other building materials. Some were designed for carrying chemicals and oil-based products. ‘Everards’ were probably the best known shippers, owning a very large fleet of coasters.

This model of a Tamar ketch was built by Chris Peacock for his narrowgauge layout based on Halton Quay at Calstock. CHRIS PEACOCK

COLLIERS

Collier ships, as the name suggests, were designed for carrying coal. The first colliers were sailing ships, fitted with square rigs. These were soon followed by the steam-powered colliers, which would be seen on a regular run sailing along the east coast. The ships would be loaded with coal in Newcastle and the other coal ports of the north-east, with most of the coal bound for London.

In this chapter I have tried to present a little background on the smaller craft to include on a model of a port or inland waterway wharf. The selection listed here should give most modellers some idea of what type of boat to include on a model. I have purposely only looked at the smaller craft, which would suit the smaller layouts. I have not included any smaller naval craft or the passenger ferries.

If you have plenty of space for your layout, then you could consider larger ships to include. The modern image modeller might be interested in producing a container port, but if this is your choice you will need a large space to include a massive container ship. A popular theme recently has been to model a military dock or quayside including a variety of naval ships.

Any model of a port or inland waterway wharf will need to feature a vessel of some kind, and whatever your choice, be prepared carry out some research. The boats will possibly be the focal point of your layout, so it is always worth trying to model them accurately.

A drifter fishing boat features on this modern image layout.

An excellent model of a steam-powered coaster with the addition of sail is shown on this pregrouping layout. Note the stacked cargoes waiting to load on the quayside. Extra detail such as this all adds to the overall scene, recreating the past in miniature.

Another fine model of a steam-powered yacht on the same layout.

The shunting operations along the quayside. This model shows high standards of both railway modelling and maritime modelling.

This model photographed at an exhibition of a canal basin depicts the murky, polluted water found in an industrial scene of the 1950s. The boat is made up from one of the kits supplied by Langley Models.

This close-up photograph illustrates the attention to detail, from the deck of the boat to the wagons on the quayside.

Another drifter fishing boat on a period model. Also shown are the different materials used on the quayside walling; of interest is the weathering applied, especially the rusting of the metal railings, and other parts. It is clear that observation of the prototype has resulted in a convincing replication on the model.

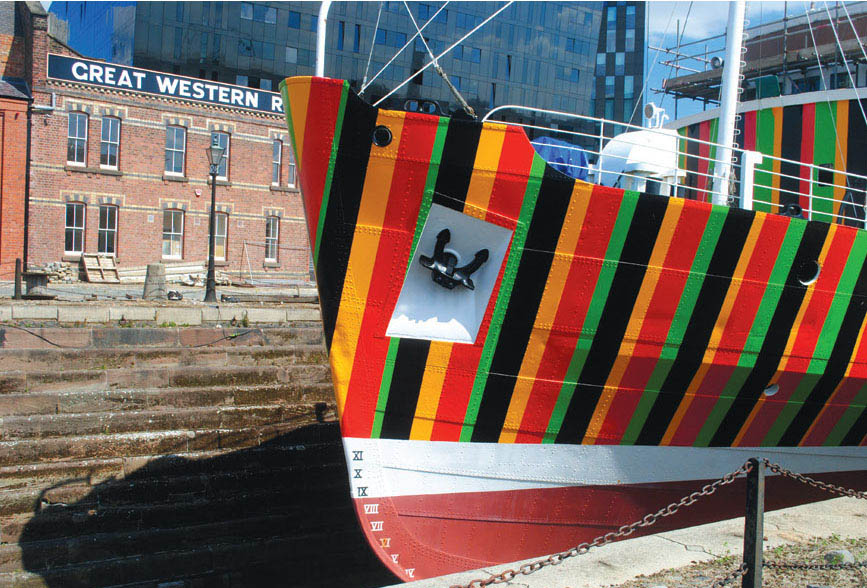

As part of the First World War anniversary celebrations in 2015, the Liverpool pilot boat Edmund Gardener was painted using a technique invented by Norman Wilkinson known as ‘dazzle’ painting. The brightly coloured stripes were to act as camouflage by breaking up the outline of the ship, thus making it very difficult for enemy submarines to identify and attack. You could have a go at replicating this on a model if you choose the First World War as the period in which to set your layout.

The deck of a steam dredger in close-up. Maintenance vessels such as this can also make interesting models.