INTRODUCTION

Following the production of my last book on modelling branch lines, it was suggested that another, similar work would be a good idea. This time, however, the subject would be modelling the railways serving the ports and inland waterway wharfs. As a young boy growing up in the 1960s I witnessed the end of steam on the railways and the decline of our major ports. Living in land-locked Derbyshire, my father would take me and my brothers to see the passenger liners and merchant ships docking at Liverpool and other major ports, and I still have fond memories of these trips, including the many dock railways in operation as well as the ships. These early recollections certainly inspired me to put this book together, and through the following chapters I have presented a comprehensive collection of reference material, and I hope have also given a good selection of layout ideas.

It was always my intention to present a mainly visual book for this subject, using both illustrations and photographs as a guide, so making the book a valuable addition to any keen modeller’s collection. I also sincerely hope that the contents of this unique publication will inspire you to build a model railway with connections to an inland or coastal port.

A BRIEF HISTORY

If we go back through history we will find that the earliest methods of transportation were by water. The sea and the rivers were the obvious choice, and our ancestors built primitive boats for moving both people and goods around. The rivers were made more navigable, and sheltered ports and harbours started to be built on the coast and along tidal river estuaries. However, the main choice of transportation inland to carry goods was the packhorse, and a number of drovers’ roads criss-crossed the country. Later, turnpike roads were built, with horses and carts carrying the bulk of the goods, and stagecoaches transporting passengers.

During the mid-eighteenth century there were further innovations to transportation in Britain. In this period the country experienced the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution, and with it the creation of the canal system. Moving goods on specially built waterways proved very successful, as boats had a much greater capacity to carry goods and could offer a safer passage for any delicate cargo such as pottery.

THE EARLY RAILWAYS

The first primitive tram roads started to appear at the same time, and our railways had their origins in these. Some early examples used slabs of stone with a groove cut into them, in which the wagon wheels would run. Most of these tramways would link quarries or mines to a transhipment point alongside a canal, while others connected with a coastal or river port. A good example of one of these was the Haytor Tramway, which transported quarried granite down from Dartmoor to the Stover Canal; the stone would be loaded on to boats to continue the journey by water. The canal had been cut to create a link with the River Teign estuary.

The Haytor Tramway was built to transport granite down from the quarries on Dartmoor to the Stover Canal. Barges would then take the cargo along the short length of canal to the Teign estuary and Teignmouth, where it was trans-shipped on to larger ships.

The Ticknall Tramway carried lime from the lime kilns near Ticknall to be trans-shipped on to narrowboats on the Ashby Canal. The picture shows the old tramway bridge at Ticknall being investigated by members of Burton Railway Society.

This was still a long time before the invention of the steam locomotive, with teams of horses providing the motive power to pull trains of loaded and unloaded wagons.

During the Industrial Revolution the innovative procedure of smelting iron meant that this material could be used to make rails; the rail sections could then be easily mounted on to a stone block sleeper. Thus the first proper railways were created, and it wasn’t long before these were used to transport materials. Experiments were being made to develop the steam locomotive, with Richard Trevithick leading the way, although horses were still used in those early days.

One of the stone block sleepers used on the tramway.

Nevertheless the iron horse soon started to replace its live counterpart. The steam locomotive was first introduced on the Stockton & Darlington Railway in the north-east of England, carrying coal from the mines around Darlington down to the port of Stockton-on-Tees. Stephenson’s famous ‘locomotion’ became the motive power on this first steam-hauled railway.

This painting by the author depicts coal being loaded by hand from railway wagons on to the narrowboats at Hartshay Wharf. The coal was extracted from the colliery nearby and shipped along the Cromford Canal by boat. Most of the coal was destined for the engine houses along the High Peak Railway.

Other minerals, mined and quarried, were transported by the tramways and railways from their source to be trans-shipped later on to boats. North Wales became Britain’s centre for slate production, with large quarries extracting this roofing material in vast amounts. All this was transported by rail down to the ports on the coast. Unlike the Stockton & Darlington where the gauge was wide, these railways were built to a narrow gauge.

The Ffestiniog Railway was one such narrowgauge railway constructed to transport massive loads of slate from the mountain quarries at Blaenau Ffestiniog down to waiting ships at Porthmadog. The narrow-gauge system was ideal for the mountainous terrain of North and Central Wales. Besides the Ffestiniog, many other railways were built to narrow gauge and are still running today, although nowadays the trains carry tourists rather than slate.

By the middle of the nineteenth century the railway system had spread to all parts of the country, the majority built to the standard gauge of 4ft 8½in. The exceptions to this were the narrow-gauge railways and the 7ft broad gauge favoured by Brunel for his Great Western Railway. The port of Bristol and others in the West Country had railways built to this larger gauge originally.

PORTS AND INLAND WATERWAYS

The ports grew rapidly during this period, with the country exporting British-made products all over the world, while at the same time raw materials and food produce were imported through our coastal ports. The railways became the major way of transporting all these goods, while inland they also played their part in linking up with the canal wharfs, where goods and produce were trans-shipped between the two forms of transport.

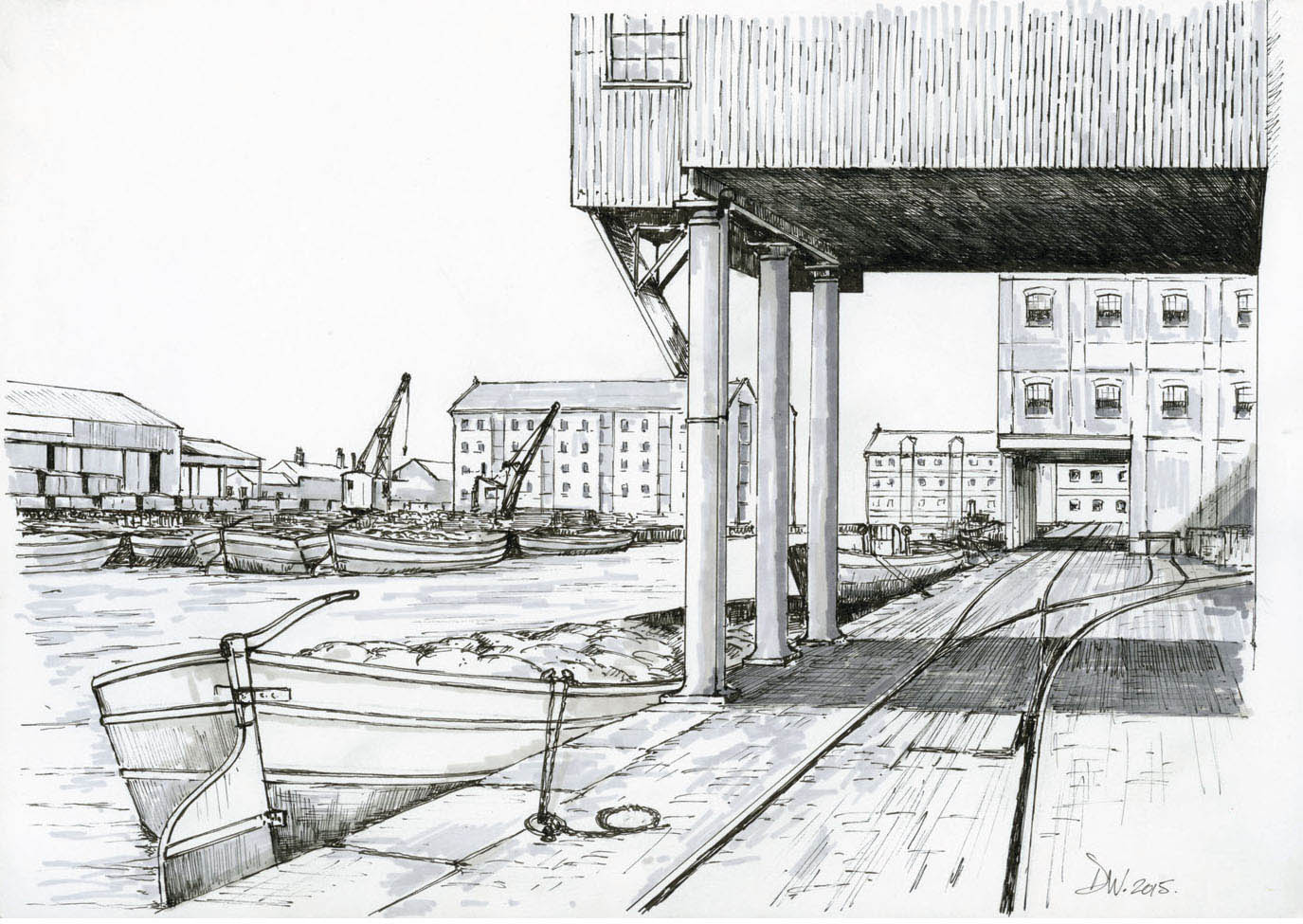

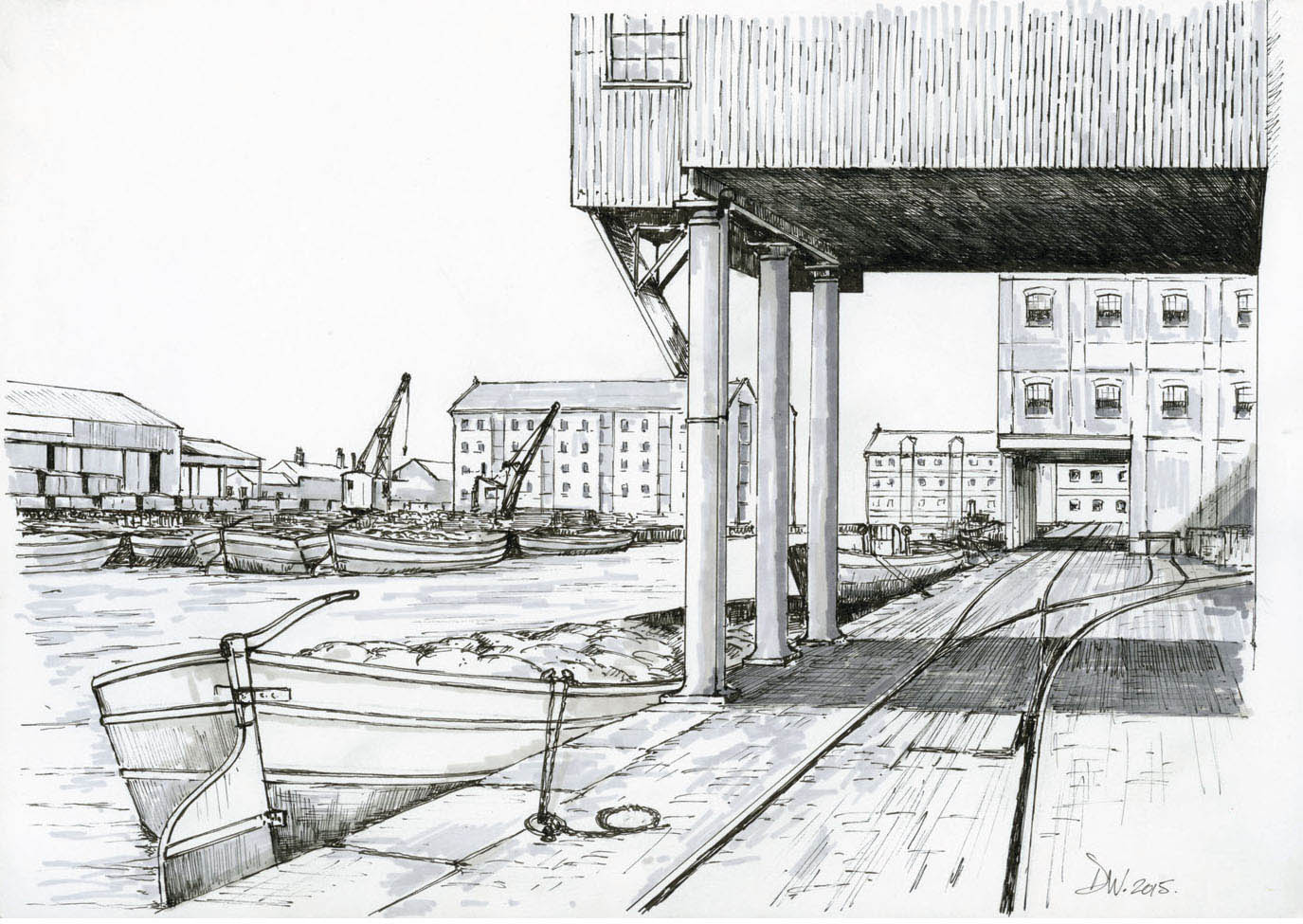

The extensive docks built at Gloucester; this view looks along the main dock with the massive warehouses in the background.

In this illustration I have purposely drawn the Bankers Quay side of the docks, to show the tracks of the LMS running along the quay and under the front of the warehouses. The GWR wharf area is seen across the dock, with the transit shed visible in the background. The illustration has been drawn from a photograph taken in 1937.

The boatbuilding and repair dock on the River Stour at Flatford. The river’s traffic would be mainly bricks, coal and corn carried by the local river barges known as ‘lighters’. The dock was the subject for one of the well known works by the famous landscape artist John Constable.

The larger ports developed their own internal railway systems, with tracks running right on to the quaysides. Some included specially constructed loading devices, such as the coal staiths where loaded wagons could be tipped, with the aid of a chute, directly into the holds of waiting collier ships. These were a common sight in the ports of the north-east of England such as South Shields. Another port specially built for the trans-shipment of coal from rail to be loaded on to ships was Goole in Yorkshire. This port was not situated on the coast, however, but was located inland on the River Ouse, which was navigable and linked directly to the Humber estuary. This inland port was built by the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway Company. The railway introduced two specially designed coal tipplers in 1879, originally constructed from timber; they were replaced with steel structures.

Goole was also well known for its unique system of transporting coal from the Yorkshire coalfields along the Aire & Calder Navigation. This specially built, wide canal allowed trains of loaded rectangular tubs known as ‘Tom Puddings’ to be pulled by tug boats to Goole. Here the tubs were floated into a massive hoist where they were raised and tipped via a chute into the holds of the ships. One of these special structures still exists and has been listed. Other ports used cranes fitted with grab buckets, which were also used for loading coal.

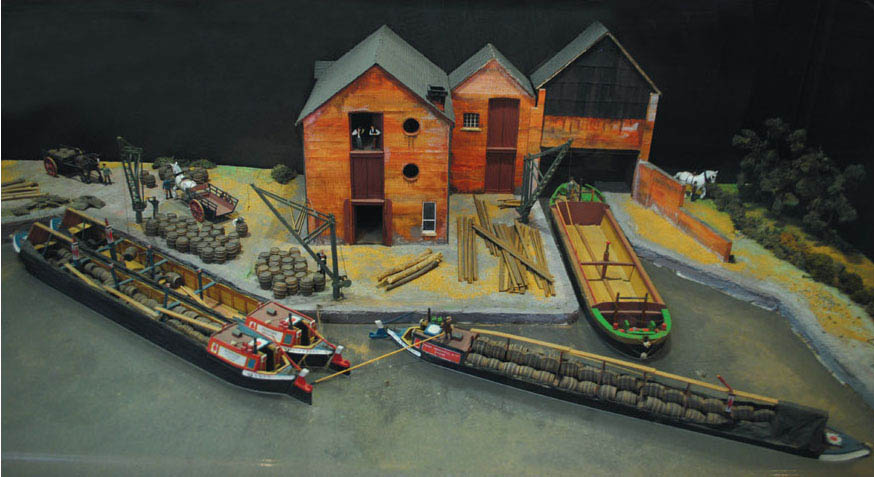

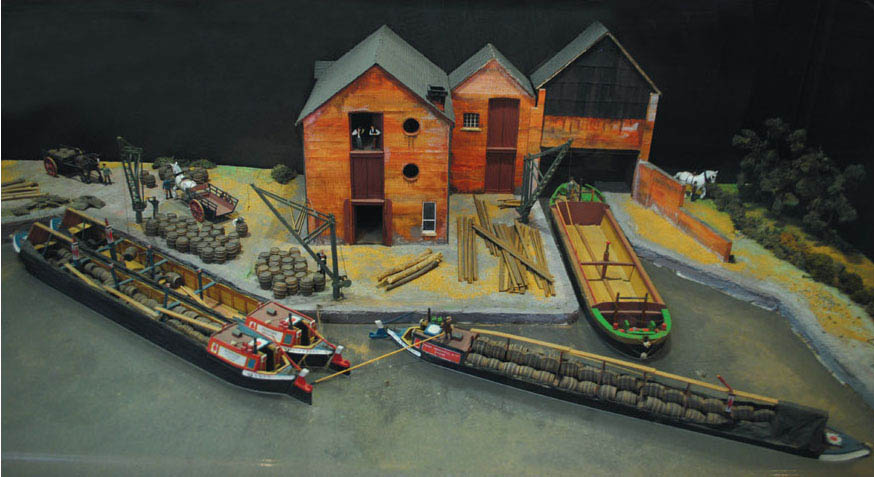

I have included this painting I produced some years ago, as it depicts a typical canal loading wharf. The location is Horninglow Basin, on the Trent & Mersey Canal bordering Burton-upon-Trent. Note the Fellows, Morton & Clayton boats in the early livery: this carrier was common in this area, plying a trade between Nottingham and Birmingham. Also of interest is the warehouse on the far right: it is built over the canal so that the cargo can be lifted directly into the building from the inside, thus keeping the produce dry. This was the salt warehouse and belonged to the North Stafford Railway. The lettering on the side wall was still visible until its demise in the mid-1970s, when it was demolished for a road-widening scheme.

The warehouses at Horninglow have long since gone, but besides my painting, a super model of the wharf is included as part of the ‘Moving Beer’ display in The National Brewery Centre.

The small port of Charlestown, near to St Austell in Cornwall. The port was built to ship out china clay, although today it is used as a film set, and usually has a few preserved squarerigged ships gracing its quaysides.

Like Charlestown in Cornwall, Albert Dock in Liverpool now has a mooring for preserved maritime craft. Visiting ships can also be seen at the dock from time to time, making it well worth a visit.

Another major inland port was Salford serving Manchester, with the canal system first providing a transport system to bring in raw materials. However, the massive growth of the cotton trade meant that greater loads of raw materials needed to be moved, and this resulted in the building of the Manchester Ship Canal, whose deep-cut waterway allowed ocean-going ships to reach right into the heart of the city. A dock railway was also built to serve this new inland port, with massive warehouses and transhipment sheds.

Besides minerals, raw materials and manufactured goods, ports for the importing and exporting of food produce were built. The landing of fish required large ports to be built all round the shores of the British Isles, and fishing ports such as Fleetwood required extensive railway systems to move the fish quickly after it had been processed in order to keep its freshness. This also applied to moving the fish from the port to the market place. Special trains would be loaded at the quaysides with boxes of fresh fish packed with ice to help preserve it. Once the trains had been marshalled together, it was important that they reached their destinations quickly, so the fastest locomotives were employed.

PASSENGER TRANSPORT

Not all ports were built for handling just freight, of course: some concentrated on transporting passengers as well, and these ranged from large liner ports such as Southampton to the busy ferry terminals.

The trans-Atlantic liner services have now been superseded by the airlines, which give a faster if not quite so luxurious service. However, this special service has not died altogether, with the cruise ships retaining and giving a first-class service to the public. The liner ports were served with special train services linking the major towns and cities direct to the liner terminals. These trains were also luxuriously fitted out to the highest standards. One such train was ‘The Cunarder’, which provided the service from Waterloo to the Cunard liner terminal at Southampton, while the Great Western Railway provided ‘The Ocean Liner Service’ between Paddington and Plymouth. The trains were made up of Pullman coaches, or specially built ‘Ocean Liner’ coaching stock in the case of the latter.

We have many fishing ports around our coastline, one of the best known being Whitby on the east coast. However, the fishing industry nowadays is only a shadow of what it was.

The ferry ports also had their special services, known as the ‘boat trains’. The channel ports, and those linking the mainland and Ireland, also employed their own specially named trains, such as ‘The Golden Arrow’ and the ‘Irish Mail’. The rail connection at the ferry ports was always situated as close as possible to the ships. Some had stations built at the end of long piers, such as at Ryde and Lymington, both giving a connection to and from the Isle of Wight. Another good example of this arrangement was at New Holland on the banks of the River Humber; before the building of the Humber Bridge, a ferry was the only way of crossing the river to Hull. The station and ferry terminal were combined and built on the wooden pier stretching out into the river; I remember the station well, as it retained its pre-grouping identity right up until its demise in the 1980s. The nostalgic flavour extended to the ferries themselves, when paddle steamers were used to the end.

During the years of conflict special ports were constructed to handle the ever-increasing need to transport troops and equipment to the continent. During World War I the railways were responsible for the mass moving of troops who needed to cross the Channel to fight at the Front.

Bankers Quay showing the warehouses from a different angle. It illustrates how the fronts of the buildings are supported on pillars, with the serving railway running underneath the overhang.

This track plan drawing based on Bankers Quay has been included to illustrate the rail connection along the quayside. I hope it will be useful for those modellers attempting to use this prototype for a model. A) warehouses B) goods offices C) loading cranes.

THE MODERN PORTS

To conclude this introduction it is worth looking at the modern ports. Today most of our consumer goods are imported from the Far East, and just about all this traffic is now containerized, requiring massive ships, which make the journey to our shores stacked high with containers. Special container ports have been built so that these goods can be handled quickly, such as at Felixstowe and Tilbury, while a new port is being built at Seaforth on the Mersey. Railheads have been built into all these ports, and a good number of the containers are craned directly from the ship to the special wagons. The lengthy trains then take the containers to distribution warehouses located in the centre of the country.

We have seen the heyday of our ports and the railways serving them, and many have disappeared over the last five decades – although it is not all bad news. Today and in the future the new container ports and railways will continue to be a major industry, serving the ever-increasing demands of our modern lifestyle.