One

THE EARLY YEARS

From the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor, and particularly after Victory in Europe Day, Americans were faced with images of the progress of the war in the Pacific, both in the newspapers and the newsreels at the movies. Naval aviation featured heavily in those images, with the dashing aviators and newest, fastest aircraft landing on carriers in the middle of the Pacific. Once the war was over, the Navy no longer enjoyed that publicity. In the Navy’s Office of Information worked one of those aviators, Comdr. LeRoy “Roy” Simpler, of Squadron VF-5 on the USS Saratoga (CV-3), a veteran of air battles over the Solomon Islands and Guadalcanal and a Navy Cross recipient. Although barnstorming and other air shows had been going on almost since aviation itself, there was no official flight demonstration team sponsored by any US armed forces. The French Patrouille de France (PAF) had formed in France in 1931 and, in 1947, became the demonstration team of the French air force. Simpler’s idea was for an official team, sponsored by the Navy, to be an important tool for recruitment, budgeting, and publicity. He took the idea to Adm. Chester W. Nimitz, who liked it and asked the chief of naval air training in Pensacola, Vice Adm. Frank D. Wagner, who passed the message on to Rear Adm. Ralph E. Davison, who headed the Naval Air Advanced Training Command. The message was passed down the chain of command until it reached Comdr. Hugh Winters, whose chief flight instruction officer was Lt. Comdr. Roy Marlin “Butch” Voris. Winters informed Voris that the chief of naval operations (CNO) wanted recommendations and ideas for a flight demonstration team and Winters wanted Voris’s input. Voris spent some time sketching out ideas and taking planes out experimenting maneuvers he felt might demonstrate the Navy’s ability to “Fly-Fight-Win.” Little did he know when he passed his ideas back to his superiors, he would be the one to build the team from the ground up. The first few shows were primarily for Navy leaders until the Blues’ first show at their first home base, NAS Jacksonville, on June 15, 1946. From there, the popularity of the Navy’s Flight Demonstration Team surged like the opposing solo performing a vertical roll. Except for a brief hiatus during the Korean War and in 2013 because of budgetary issues, the Blues have continuously amazed and inspired millions in dozens of nations for over 70 years.

In 1927, naval aviator D.W. “Tommy” Tomlinson watched the National Air Races at Spokane, Washington, in some frustration. The Army’s demonstration team, the Three Musketeers, “stole the show,” as Tomlinson described it later. As executive officer (XO) of VF-6 at North Island, he immediately began to make adjustments to the Boeing F2Bs in his squadron to facilitate acrobatic flying. The team of three became known as the Three Sea Hawks, Tomlinson flying with future admirals William V. “Bill” Davis and Aaron “Putt” Storrs. By 1929, the three had been relocated, and that was the end of the Three Sea Hawks.

After Bill Davis was sent to Pensacola, he joined with other naval aviators and formed the Three T’Gallants’ls (a reference to top gallant sails of a ship, as well as gallant souls who sailed them), flying here in Boeing F2B fighters over NAS Pensacola.

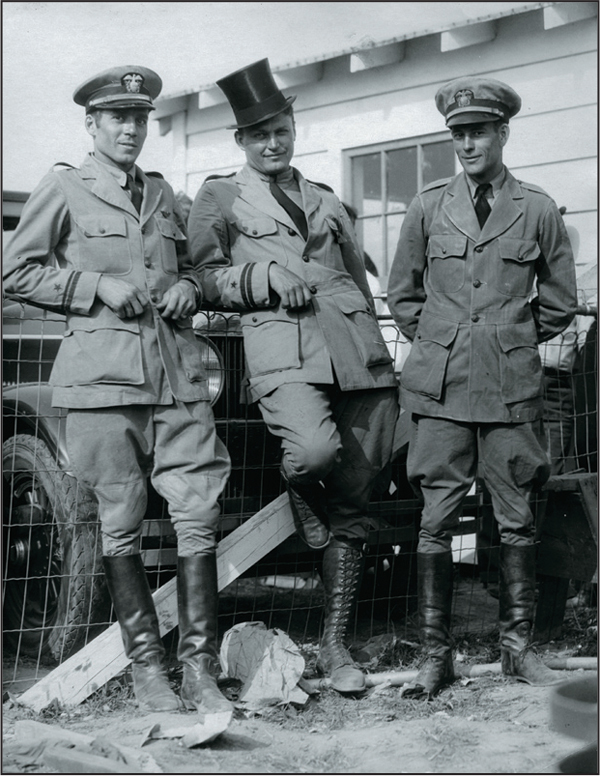

On the heels of the Three T’Gallants’ls were the High Hatters of VF-1B, flying from the decks of the USS Saratoga (CV-3). As an acrobatic team, the High Hatters was a nine-man team flying the Boeing F2B-1s roped together—even during taxiing. They appeared at the 1929 National Air Races in Los Angeles along with Charles Lindbergh. Each of the High Hatters— pictured here, from left to right, Lt. Frank O’Beirne, Lt. Leslie Gehres, and Lt. Frederick Kivette— distinguished himself during World War II and achieved flag rank. (US Navy photograph, courtesy of the Naval History and Heritage Command.)

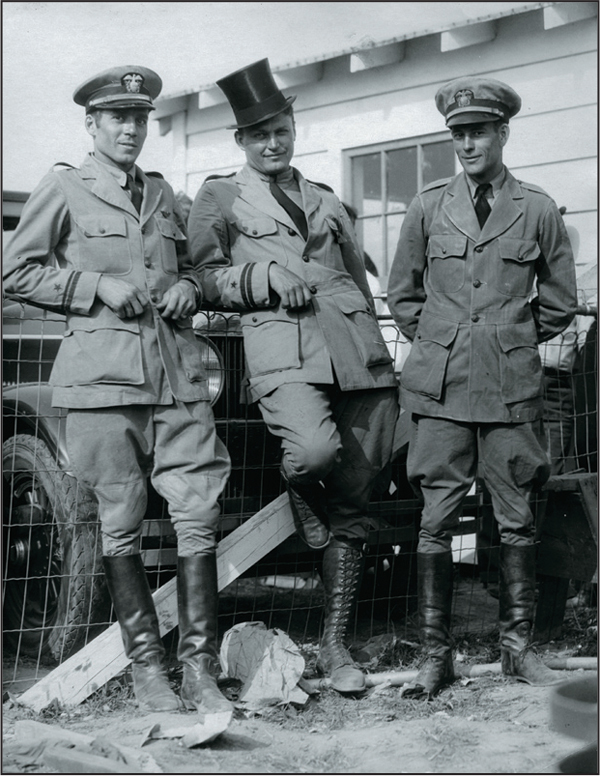

On the East Coast, the Three Flying Fish were assembled at Anacostia, Maryland, by Adm. William Moffett and flew the Curtiss F6C-4. Lt. Alford Williams, Lt. Frederick Trapnell, and Lt. Putt Storrs began the unit and, on Williams’s departure, were led by Lt. Matthias B. Gardner. Trapnell later became the first naval aviator to fly a jet (the Bell Airacomet) and Gardner commanded the USS Enterprise (CV-6) during some of her most significant Pacific battles. Pictured from left to right are Storrs, Gardner, and Trapnell. (US Navy photograph, courtesy of Frederick M. Trapnell Jr. and Dana Trapnell Tibbits, the authors of Harnessing the Sky.)

Not to be left out, Marine Corps Aviation was making a name for itself flying from Quantico, Virginia. In 1925, officer in charge of Marine Corps aviation Lt. Col. Thomas C. Turner made enough noise to convince Adm. William A. Moffett to issue a directive authorizing three flying squadrons for the Marines. VF-1 and VF-2 teamed up to perform for the first time in public at the Philadelphia Sesquicentennial Exposition in 1926. Here, a formation of Boeing F4B-3s of VB-4M shows the skill of Marine Corps aviators in the 1930s.

Adm. Chester W. Nimitz, chief of naval operations, authorized the creation of an official flight exhibition team for the US Navy in 1946, messaging the Naval Air Advanced Training Command in Pensacola to organize a team to “be employed to represent the navy, as deemed appropriate and when directed, at suitable air shows and similar events.”

LeRoy “Roy” Simpler had been the captain of VF-5 on the USS Saratoga (CV-3) during World War II. After the war, he worked in the Office of Information, the Navy’s public relations arm. He recognized the importance of preserving the heroic and enduring image of naval aviation and keeping it before the public and that a flight exhibition team would be the ideal way to do so.

Lt. Comdr. Roy Marlin “Butch” Voris was a veteran of the war in the Pacific, flew hundreds of missions, became an ace, was shot down over Guadalcanal, and was awarded three Distinguished Flying Crosses, a Purple Heart, and twelve air medals. The early air shows were made up of maneuvers honed during the war. Many of his experiences in the war were groundbreaking, as was his work with the Blues. His leadership experience also guided him when it came to assembling a group of pilots who could be molded into the finely tuned team they were and are still today. After the war, Voris became an advanced flight instructor and used the time to build what Robert K. Wilcox calls “the beginning of ‘show’ mentality” as he trained pilots and gave demonstrations of what naval aviation was capable of.

The first public flight of the Navy’s new Flight Exhibition Team happened on June, 15 1946, in front of a crowd of 35,000 and took place at Craig Field, Jacksonville, Florida. Flying No. 1 was Butch Voris. As he says in an interview in First Blue by Robert K. Wilcox, “You could see them all waving handkerchiefs and clapping their hands,” as he taxied in. And then about being presented the trophy, Voris says, “It was a big surprise. It was for the best performance of the air show.”

The original team of three flew the Grumman F6F Hellcat, chosen because Voris had flown it in the Pacific during World War II and knew what kind of performance it was capable of. Voris is in No. 1; No. 2 is flown by Maurice “Wick” Wickendoll, a pilot who flew with Voris in the Pacific; and in No. 3 is Lt. Melvin W. “Mel” Cassidy. The show was 12 minutes long, described by Voris in First Blue as “twelve intense, breath-holding minutes of grunt, pull, turn and roll.”

After its first public performance at Craig Field, the team was awarded this trophy for “the Finest Exhibition of Precision Flying” at the Southeastern Air Show and Exhibition on June 15–16, 1946. Today, the trophy occupies a place of honor in the ready room at the Blue Angels headquarters at NAS Pensacola. The base newspaper proclaimed, “Naval Flight Team to Star in Jax Air Show,” and that it would “commemorate the dedication of Craig Field.”

Here, the Hellcats are lined up at Craig Field. The planes had come from the fleet but had been rebuilt and lightened as far as possible and painted in the blue and gold chosen by Voris. Grumman also sent three technical advisors to help get the planes ready: Bill Babington, Fred Benson, and Albert H. “Goldie” Glenn.

This is an early photograph of team members, from left to right, Lt. Alfred “Al” Taddeo, Lt. Gale Stouse, Lt. Comdr. Roy Marlin “Butch” Voris, Lt. Maurice “Wick” Wickendoll, and Lt. Melvin W. “Mel” Cassidy posing in front of their Grumman F6F Hellcat. Stouse and Taddeo came aboard after the initial success at Jacksonville. Stouse would fly the SNJ, known as the “Beetle Bomb.”

To demonstrate the kind of aerial gunnery and maneuvers used in World War II, a simulated dogfight with a SNJ Texan trainer painted to look like a Japanese Zero was a feature of the early shows. As part of the stunt, a dummy dressed in a flight uniform filled with sawdust and attached to a parachute would be thrown from the plane.

While the team was giving its fifth public demonstration at NAS Pensacola for Navy brass, the dummy landed just feet from an admiral, with sawdust going everywhere. On landing, Voris was pretty sure a court-martial was waiting for him. Instead, he was counseled to “move it out a little further.” Here, Voris is trying to explain to the admiral just how the stunt was supposed to have worked.

Playing an essential part of the Blue Angels team is the maintenance crew. Here is the crew Voris chose to keep the Hellcats—and later, the Bearcats—flying. The men standing are, from left to right, unidentified, Butch Voris, L.R. Reid (Voris’s plane captain), and unidentified; kneeling is R.M. Boudreaux.

Voris is being checked by his plane captain, L.R. Reid, before flight in his Bearcat around 1946. Other team members chosen by Voris were: C.W. Barber, R.M. Bourdeaux, L.J. Johnson, W.E. Stanzeskim, H.B. Hardee, W.L. Miller, J.D. Turrentine, C.H. Casey, C.C. Hicks, and T.P. Valentiner.

This early team insignia blends the World War II propeller-driven planes flying in formation with the jet launching from a straight-decked aircraft carrier. The title “Flight Exhibition Team” is a bit ponderous and definitely not glamorous. Early on, a contest was held in the Jacksonville newspapers for a new name for the team. Somehow, the right name had just not come to anyone until Wickendoll spotted the name of a famous nightclub in New York City: the Blue Angels. In an interview for the book Blue Angels: 50 Years of Precision Flight by Nicolas A. Veronico and Marga B. Fritze, Voris’s response to Wickendoll’s suggestion was “Gee, that sounds great! The Blue Angels. Navy, blue and flying!”