Back in the seventies British Airways flights out of Saudi Arabia’s east coast departed at one o’clock every morning. Check-in began shortly before midnight. Ed and I would spend the witching hour in one of those seventies airport departure lounges where there was nothing but uncomfortable chairs and the toilet. It was a joyless wait. Through the glass we watched the Dhahran dark, the red lights running away into the desert.

By the time we boarded I was empty, or hungry, I was never sure. But all I remember of those in-flight meals is the sharp orange juice for breakfast. It was as bitter as the five o’clock London morning into which we flew.

During those journeys we were labelled, literally, with red-and-white stripy tickets and a large name badge slung around our necks. The first time, we were picked up before dawn by a ‘proxy parent’, one already in her senior years. The school sleeper train didn’t leave Euston until eight that evening.

Near Leicester Square we ate ‘luncheon’. There was white table linen and stodgy food. Ed spoke little, or not at all. I tried my best. Even in the cinema, watching Moonraker, I couldn’t concentrate for her resentment. It sat square amongst us the entire day.

This arrangement with Universal Aunts was not repeated. A day’s entertainment in central London cost the same as a domestic flight north to Aberdeen. Thereafter we were dragged by equally resentful unaccompanied-minor minders the length of Heathrow’s warren of underground passageways between Terminals 3 and 1 to meet the first flight of the day north. One letter home from Ed reads that our minders ‘just stood there for ten minutes having a granny’s conversation about tights!!!!!!’

While he worried that we would miss our flight, I worried we would crash. Following an episode where we had to ditch in Kuwait City after an engine fire, my mother had begun listing in her letters to me some of the world’s commercial flight disasters. The PIA incident in Jeddah where all 145 passengers and eleven crew died due to a fire in the cabin, and the Garuda Douglas DC-9 hijacked by Komando Jihad. My letter of 6 October 1980 reads: ‘I have just heard about the Tristar that caught fire near Riyadh, because (it is thought) a passenger was using a gas fire in the aisle. Something like 300 people killed!’

Worry was about all Ed and I did, our teeth clenched most of the way. We had long put our backs to trust, and to adults. One lesson had been clearly driven home. We were on our own.

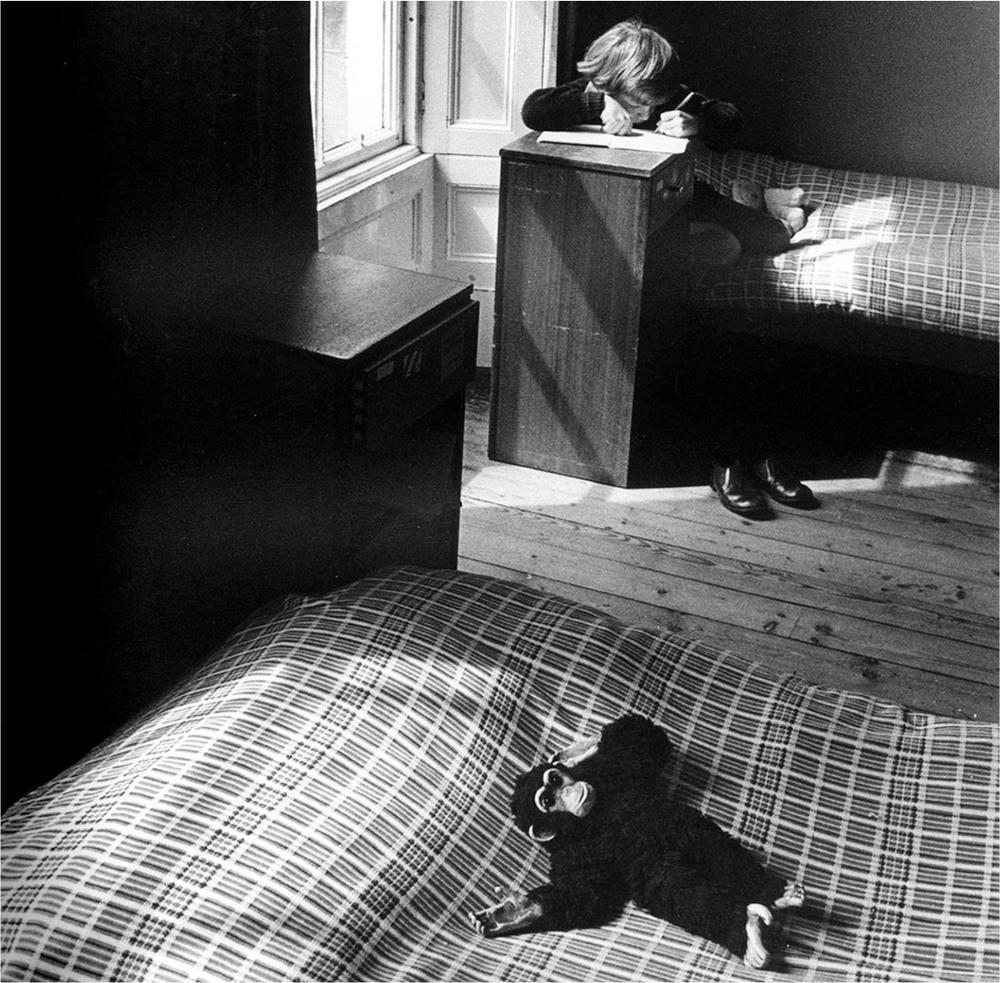

Arriving in Scotland we’d find that it was still dark, a taxi driver holding up a handwritten A4 sheet which read ‘Aberlour House’. Often we were the first to arrive. I would stray between the empty bunk beds upstairs, alone, eyeing the sticky labels on the footboards to see where everyone else was sleeping. On a bottom bunk I would find my Holly Hobbie duvet cover and pillowcase folded on my mattress and like an automaton begin to make up my bed.

As the terms away from home grew, the number of stuffed toys sharing the bed with me grew too. Soon it became difficult to find any place for myself. When I moved on to the secondary school, with regret, I threw these friends away. By the time I was fourteen, while Ed remained in our delegated seats watching the in-flight entertainment, I spent these journeys to and from school at the back of the plane, smoking, getting drinks in with single men I’d befriended in the departure lounge.

I dressed like a homeless person, battered plastic bags in a mess at my fists – wearing an Oxfam overcoat and holed shoes, an inevitable ciggy drooping from my lips. On one flight I ‘snogged’ a member of the Austrian UN Peacekeeping Force, and on another threatened to bunk with a man I’d found in Amsterdam, and leave Ed ‘to it’.

But somehow we would arrive at the customs hall in Dhahran. There, in accordance with sharia law, officials went through every piece of luggage and every women’s magazine with gloved hands. They were after evidence of bare skin: shoulders, ankles, necklines, wrists; and, struggling with their own enjoyment, they would blacken the pages with a marker and leave us to repack.

My parents had started asking me in the arrivals hall:

‘Have you been smoking?’ or ‘Is that drink I smell?’

And I’d shake my head, blundering past them with a trolley load of plastic bags, out into the warm night and the car.

Perhaps they would ask Ed too, and he would lie. All we had left of our relationship was solidarity, and just as I had not abandoned him in Amsterdam, he did not, despite his thorough disapproval, ever tell them how out of control I had become.

The Christmas of 1984 I gave the parental presents much thought. It would be a relief to be able to say that I kept their outrage to myself, so as to save Ed the anxiety. But more likely I had spent much of the journey bragging about how customs-ballbusting my gifts were.

As we approached, the queue snaked long ahead of us, and I’m sure I began to worry too. These flights were often full, and there were many magazines to blight and bags to disembowel, a process I eyed with mounting dread. Once we’d reached the front the customs official held my plastic bag upside down, its vomiting contents falling against the dam of his bent arm.

Amongst the items rolling across the table was a large tub of Johnson’s talcum that still shook its powder (though to my immense disappointment, he did not bother to check). Hidden inside the white plastic container was a collection of liqueur chocolates, which Dad eked out till Easter, leaving the Drambuie till last.

Also amongst the haul was a Playgirl, camouflaged with wallpaper. It lay unnoticed in my suitcase, along with a decoy copy of Cosmo that they so enjoyed blackening out.

The copy of Playgirl was a gift for my mother that was as much about wanting to shock her as any Saudi customs official. An early edition, it pictured double-page spreads of penises, laid across hairless thighs. These docile images came to be celebrated as the ultimate insurrection against Islamic misogyny that any of us women on the compound made. But to me the misogyny was irrelevant. I needed to escape school, and was prepared to risk – alcohol, pornography, sedition – everything to get home. That I never would, or could, has taken me decades to see. Home had long been disbanded, an irrecoverable place in memory to which none of us could return.