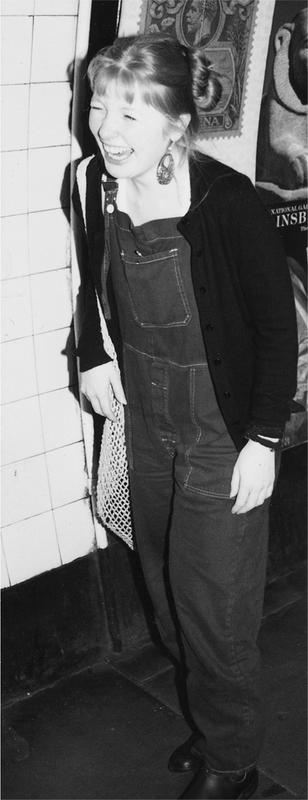

My mother often told me that weddings were the best place to meet an eligible man. Tristan, whom I picked up at a Scots Guards nuptial, was a proof of principle and to her worth any disgrace. Dropping me off at the train station she was astute enough not to enquire where I would sleep after the wedding celebrations. All I had in my handbag was an empty wallet, my toothbrush and a clean pair of pants.

Googling Tristan as I write this, I find he’s now CEO of an indeterminate financial company, which marks him out as the only solvent ex-boyfriend of mine from that period. Most of the others have gone on to become drunk, destitute or dead.

He was pale, his face eager, and the only ‘date’ we managed that winter was Disney’s Little Mermaid at the Chelsea Cinema. It was a matinee. We sat at the front.

The rest of that autumn we held hands, arms locked at the elbows, his fingers so tight in mine my knuckles flared white. Nights, at Cavalry Barracks, we squeezed illicitly into mean army-issue beds, beneath scratchy blankets. Like children we were beating back the chill of institutional rooms, shabby curtains and sixty-watt bulbs.

Then in the December of my twenty-second year Tristan was put on Royal Guard at the Tower of London. He and eight men were playing Grand Old Duke of York-type nursery games with keys, and presenting arms, and shouting: ‘Who goes there?’

I was impressed. As was Mother.

What I regret most about Tristan, and would very much like to take back, is my ill-considered ‘I love you.’ Mum must have voodooed me into it. I could not have been in love by any stretch. It takes me years to work up to love, and even longer to admit to it. Anyway I was distracted. Besides Beefeaters, mermaids and single beds my diary narrates an untidy closure with a bass player recently signed to Elektra, and intermittent phone contact with a drunk I’d hooked up with on Camden Town’s Barnet-bound platform. It also transpires I couldn’t invite Tristan round to my flat because a baggage handler from Luton had moved himself in the week before (a ‘totally platonic arrangement’, one entry reads).

But my mother and I kidded ourselves that the only thing going on was a uniformed second lieutenant on Royal Guard Duty at the Tower.

The night of the Ceremony of the Keys and Who-Comes-There, two other officers and Tristan’s sister joined us for whisky in his quarters. It was a flat with ruched curtains and the pervasive stink of prep schools and torture that haunts much of the upper classes.

We waited for the goose-stepping up Water Lane to begin, the shouts to a Yeoman, the safe keeping of keys; a ceremony which has begun every evening for centuries at exactly seven minutes to ten. We waited. Tristan’s men laid on more whisky, and more, so by ten to ten he was very much the worse for wear, his bearskin askew.

Beyond the Tower walls the city had emptied. Gathered on the cobbles the night felt to me colder and blacker than any other corner of London. I wanted to go home. It was a long way, and I was still in my clothes from the previous night.

We stood on the Broadwalk steps flapping our hands against our sides in the cold, with the small band of red-coated Guards at attention outside the Queen’s House. In the darkness came the clang of the gates, and the shout of the sentry along Water Lane.

‘Who comes there?’

And the Yeoman’s answer: ‘The Keys.’

The boots of the Warder and his military escort echoed along the cobbles, up under the Bloody Tower Arch till they were beneath the steps.

Tristan bellowed some incoherent orders, the December air clouding in huffs around his face. Wobbling on his about-turn, he provoked tuts from the Freemen of the City. One hissed: ‘Drunk!’

The keys were marched to the Queen’s House and over the wavering call of the bugle the Freemen filed off.

When we called by the flat to say goodbye, Tristan already had his bearskin off, the buttons on his tunic wrenched undone. He was bent over the laces of his boots.

Tristan hated to be left. When he was in barracks, although it was forbidden, he would beg me to stay. He was like the small child abandoned in a chilly prep school, desperate for his mother, and every other institution that followed mirrored the abject loneliness of the first. His pleas for me to stay woke the buried child in me. I did not care that I might be caught.

But the Tower was different. No woman stayed overnight. It was completely beyond the pale. For twelve hours every night, ten to ten, the Crown Jewels and their guards were, and are, locked in. Nothing transgresses this rule.

Tristan, drunk, pulled me down beside him, pleading in whispers, his eyes on my shoes. Bereft at the thought of a night alone he did not notice the uncomfortable departure of his sister and the two other officers, nor the clangs and jangles of the Tower going into lockdown for the night.

It says in my diary that I ran him a bath. That we shared it, and slept.

It was five forty-five when I woke, dawn still a long way off. Two hours till the office opened, a tube ride away in Bloomsbury, four until the gates unlocked. Again he pleaded. Please, please would I remain until the Tower was opened to the public at ten?

To save my job I couldn’t, and by ten past six on that December morning Tristan, on guard at the Tower of London, was back in uniform. Alone he marched me down towards Water Lane, a grave silhouette in front. His platoon, on guard, whistled in low tones as we passed, the darkness colder and blacker even than the night before.

At the first gate, beneath the Byward Tower, Tristan knocked on the door, rousing a furious Beefeater. I remember only a huge brass plate: ‘Yeoman’s Gaoler’, and his quantity of keys. Tristan gave an exaggerated salute. Then we bent beneath the slender rectangle of door in a massive gate, our line expanded to include the Yeoman of the Guard. I was marched over the stone bridge to Middle Tower. No word passed between us, Tristan standing to attention as the keys were inserted in the final lock and the handle turned. It was only when at last I struggled through the second cutout door onto Lower Thames Street that I heard him murmur to the Beefeater:

‘I found her with one of the men.’