HOW SPARKLING WINES ARE MADE

AND HOW THEY TASTE

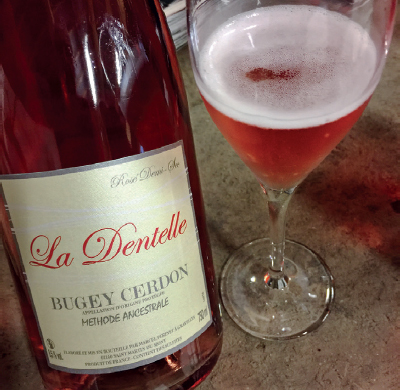

More than 98% of grapes grown in the Diois are made into sparkling wines and about 90% of these are Clairette de Die, made semi-sweet in the ancestral method; in Bugey 65% of production is sparkling (with more than half in Cerdon); currently less than 6% is sparkling in Savoie, but there is a steady increase, as demand for sparkling wine rises. Some sparkling wine is also made in Isère and Hautes-Alpes.

It has long been known that marginal climates – regions where grapes struggle to ripen – are ideal for the production of sparkling wines because of the natural high acidity and low sugar levels in the grapes. The age-old stories of ‘wine coming back to life in the springtime’ have often been explained as malolactic fermentation, but could also have been due to warm spring temperatures causing the natural yeasts to restart their work after an incomplete fermentation. This is the essence of the original ancestral method of making sparkling wine, and of the Méthode Dioise (see History, here) and indeed of Pétillant Naturel, a style of wine that has come back into fashion in regions such as the Loire Valley, Beaujolais and the Jura. Today Clairette de Die, Bugey Cerdon and two other French AOC Méthode Ancestrale wines, Limoux and Gaillac from southwest France, exist in a modernized form, which is explained in this chapter.

Ayse – today, usually Ayze – in Haute-Savoie has a long history of sparkling wine production.

Traditional method wines, made as in Champagne, also have an established history in the Alpine regions, largely thanks to the former worldwide success of Savoie’s sparkling Seyssel. Other pétillant (lightly sparkling) and mousseux (sparkling) wines have also been made in small quantities all over Savoie, notably in Ayze from the Gringet variety. From the 2014 vintage the Crémant de Savoie AOC has created a more regulated style of traditional method sparkling wine, with production methods similar to those that apply for all Crémants. Dry Bugey AOC sparkling wines are also made by the traditional method.

All these dry sparkling wines do well in their local French markets due to their good price points and overall decent quality; Savoie’s Crémant designation aims to increase visibility.

Crémant and the traditional method

After making a base wine blend, the traditional method involves bottling with added yeast and sugar to provoke a second fermentation in the bottle. The bottles remain for at least nine months sur lattes (ageing on their sides, with the wine in contact with the second-fermentation lees). Riddling follows to shake down the sediment, either manually or more often semi-automatically or automatically in a gyropalette, and then disgorgement to remove the sediment. Finally, the bottles are topped up with wine – usually including dosage (a sugar and wine mixture) – and then sealed with cork. Crémant must not be bottled before 1 December after the harvest, meaning that the earliest it can be disgorged is in September the year following the harvest. Bugey Montagnieu must, like Crémant, be hand-picked and must spend at least 12 months in contact with the lees.

With the exception of the Diois, very few wineries in these small regions are equipped for bottling, riddling and disgorgement. In Savoie and southern Bugey most vignerons use the local service provider CMC, which has facilities near Chambéry and in Bugey. Some, especially in Seyssel, use a sparkling wine service provider in the Jura to the north. Shared equipment, usually through a CUMA, is widely used, such as in Cerdon. Even when the wine is disgorged elsewhere, the vigneron will specify the level of sugar for the dosage.

Although the method must be conducted correctly, the keys to quality traditional method sparkling wines are the original base wine quality and the length of time the wine spends sur lattes.

Traditional method sparkling wine styles and tastes

Bugey white sparkling wine is usually brut, though there is a small amount of the sweeter demi-sec, especially for rosé, and a small, but increasing, amount of the much drier extra brut or brut zero. The base is often Chardonnay alone, but it may also be Molette or Jacquère, or a blend of any of these with small amounts of Aligoté, Altesse or red grapes. These sparkling wines are simple, fresh and rarely have depth of flavour or great length, but there are some finer examples, especially those from Chardonnay and Pinot base wines, and those that have spent longer than the minimum nine months sur lattes. The region is not seeking a Crémant appellation, mainly because it doesn’t think growers will want to be forced to harvest manually.

Bugey Montagnieu sparkling wine (white), from any or all of Altesse, Chardonnay and Mondeuse, is usually a big step up in quality, with much more elegance, some spice, occasionally an attractive floral or vegetal character, and better length too. Depending on the producer, these are among the finest dry sparkling wines of the French Alps. Production is limited to 150–200,000 bottles annually.

The Royal Seyssel brand is made in the traditional method from Altesse (aka Roussette) with Molette.

Sparkling Seyssel is in flux at present and there is a wide range of qualities of brut and demi-sec styles among the dozen producers, who make 100–200,000 bottles. Gérard Lambert makes the brand Royal Seyssel, which lives up to its name, with zingy, fresh and long-aged cuvées that are well worth seeking out. The base wine is supposed to be a minimum of 75% Molette with Altesse, but several producers do not have sufficient Molette and this is being reviewed.

Thanks to Domaine Belluard, today Ayze is the most famous French Alpine sparkling wine among rare wine aficionados worldwide. Dominique Belluard takes extra care in producing his Gringet grape base wines and keeps them sur lattes for longer than usual. The result is a sparkling wine epitomizing mountain freshness combined with ripe, delicately exotic fruit. There are other good Ayze sparkling wines from Domaine Montessuit and more artisanal versions from some tiny vignerons – between them all they produce fewer than 100,000 bottles annually.

Crémant de Savoie has been made only since the 2014 vintage, so at the time of writing the base wines have come from five very different vintages, from the relatively cool 2014 to the very warm 2015 and 2018. Apart from variations in vintage, wine styles vary widely between those who make 100% Jacquère and those who blend the minimum 40% Jacquère with Altesse (the two must together make up at least 60%) and/or Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, all of which add richness, character and length to the Jacquère. In the haste to launch the new AOC, early releases had only the minimum nine months on lees and some producers still give less than a year; in my view they need longer on lees to taste good, and a handful of excellent ones have now emerged.

Previous to Crémant, Savoie traditional method wines made with at least 18 months sur lattes showed potential. Many Savoie producers continue to produce pleasant traditional method pétillant (lightly sparkling) and fully sparkling wines that do not adhere to Crémant rules – these are now sold as Vin de France.

There is a small amount of dry AOC rosé sparkling wine from both Savoie (not allowed the Crémant designation) and Bugey, often from Gamay base wines – freshness and fruit should be their hallmarks. Some demi-sec rosés are made too.

Clairette de Die Brut, which can be disgorged traditionally or transferred to a tank for filtration, has a distinctive character from its base wine of 100% Clairette. The grape can confer bitterness, but if the time sur lattes is long enough the wine – made in small volumes – can be very enjoyable, with a grapefruit twist. Crémant de Die is also a relatively small production, made from a minimum of 55% Clairette, with some Aligoté and occasionally a dash of Muscat. There are some attractive examples, especially when producers give two or more years of ageing sur lattes. It must be brut, with less than 15g/l of residual sugar. Citrus flavours are often to the fore and most Crémant de Die is a better choice than Clairette de Die Brut, the blend of grapes and extra care adding depth.

Ancestral method

The essence of the ancestral method is that the bubbles are produced by a single fermentation, which is stopped in tank and then restarted in bottle without any additions of further yeast or sugar. Historically, the wine was sold with its sediment; once filtration techniques came along, the sediment was filtered out and high levels of SO2 were used to stop fermentation continuing. The arrival of cellar refrigeration equipment along with advances in filtration revolutionized the way the ancestral method was conducted. Despite its name, which implies ancestral traditions, it is thanks to modern technology that commercial quantities of these semi-sweet sparkling wines can be made efficiently and shipped all over the world.

Clairette de Die Méthode Ancestrale (sometimes referred to as Tradition), based on Muscat à Petits Grains, and the Gamay-based rosé Bugey Cerdon are essentially made in the same way, with some minor differences.

1.After picking at a potential alcohol of about 10–11%, the grapes are pressed; the must is occasionally enriched and is chilled down to 10°C or below and settled for 24 hours.

a)Cerdon: the Gamay grapes are given a few hours of maceration before pressing; if used, the delicate Poulsard grape is usually given less maceration time or simply pressed directly.

b)Clairette de Die: to have an extremely clear juice to give purity of flavour, earth filtration, bentonite and addition of enzymes are very commonly used.

2.The clear musts are transferred to temperature-controlled tanks where fermentation begins slowly with natural yeasts (used by most producers), although cultured yeasts are not forbidden. Both the Diois and Cerdon claim to have a natural yeast present on their terroir, Saccharomyces uvarum, which is able to function at temperatures below zero degrees Celsius. The temperature is kept low to create a very slow initial fermentation, leaving much of the sugar unfermented.

The largest producer of sparkling wine in the French Alps is the Jaillance co-operative in Die.

a)Cerdon: generally fermentation starts at around 10°C, rarely more than 13°C. It is then gradually reduced to zero degrees or even as low as –2°C.

b)Clairette de Die: fermentation temperatures vary between producers but Jaillance, for example, ferments between +2°C and –2°C; some producers ferment at higher temperatures, up to 10°C.

3.Once the alcohol level reaches about 6% in Cerdon, or between 2% and 5% in Die, the wine is chilled to 0°C or lower and given a rough filtration to reduce the yeast population. Fermentation stops due to the cold and the lack of yeasts. The part-fermented wine is then maintained in tank at 0°C or lower before blending and bottling. In both regions, there is a little blending between the ‘current’ and previous year’s musts, but the vast majority of wines are from a single (rarely marked) vintage.

4.The wine is filled into sparkling wine bottles with a crown cap seal. No liqueur de tirage (yeast and sugar mixture as used in the traditional method) is allowed to be added.

a)Cerdon: bottling begins as early as mid-October, depending on the harvest date, and for most producers is finished by December.

b)Clairette de Die: at the larger producers, bottling starts in about December and continues up to the end of July the following year.

5.Bottles are moved to a cellar at a temperature of 10–12°C. Fermentation restarts in the bottle, but comes to a stop naturally at an alcohol level of 7–8%, leaving a certain amount of natural residual sugar and between six and a whopping ten bars of pressure.

Some producers mark ‘Demi-Sec’ on the labels of Cerdon and almost all Bugey Cerdon fits this official sweetness category.

a)Cerdon: the wine must remain in bottle with the lees for a minimum of two months. It used to be three, but producers believe that the freshness of the style they want from Gamay and Poulsard does best with a short time on yeast. Many producers like to keep the bottles upright for a slower fermentation.

b)Clairette de Die: the wine must spend at least four months in bottle with the lees; many producers leave it for at least six months.

6.With the notable exception of Domaine J-C Raspail in the Diois and one or two others, who use traditional riddling and disgorgement, most wines are disgorged and filtered to remove the sediment. This can be direct from the original bottle to a washed bottle via a filter; more often the wine spends a short period (rarely more than 24 hours) in an intermediary pressurized tank before re-bottling (like the transfer method used elsewhere in the world). No liqueur d’expédition or dosage (sugar and wine addition) is allowed to be added. Sulphur levels may be adjusted if required, but with the use of such low temperatures, along with high dissolved CO2, sulphur levels do not need to be as high as in most wines with residual sugar. The final pressure is between three and six bars.

Bicycle pump carbon copies – Cerdon’s dark secret

From the 1950s, much Gamay in Cerdon was made sparkling simply by carbonation or pumping in the bubbles; carbonation continued even after the advances in technology facilitating the ancestral method. Although carbonated wines are not allowed to use the Bugey Cerdon label, a large number of Cerdon producers retain the carbonation unit in their cellar (which by AOC law they must detach from the bottling line each time they bottle or transfer Cerdon). They use it to produce wines for early release, sometimes Gamay rosé and sometimes whites, which often sell at their tasting rooms for just one or two euros less than their AOC Bugey Cerdon. As wine tourism increases in the region, this risks confusion, even if quantities remain small. I wish the local syndicate would ban their members from using it.

Ancestral method sparkling wine styles and tastes

Bugey Cerdon could be described as the original, semi-sweet, eminently quaffable and delicately low-alcohol sparkling pink. The best are simply delicious, to drink without too much thought at any time of day, especially in summer. Vignerons recommend that Cerdon is purchased in spring or early summer following harvest and consumed within 6–12 months. The best can age somewhat longer, but it’s not to everyone’s taste. Cerdons have a bright, intense pink colour; the very few made with more than 50% Poulsard tend to have a paler, rose-pink colour. My favourites show wild strawberry flavours, sometimes even rosehip, on the nose and have real zippy acidity along with their sweetness and a crisp long finish. Sometimes a little grapefruit shows through if Poulsard has been used. The AOC specifies residual sugar of 22g/l to 80g/l in the finished wine – most are between 45g/l and 70g/l; each grower has his own style or may make several cuvées. Alcohol levels vary between 7% and 8.5%, depending on sweetness.

For Clairette de Die Méthode Ancestrale, the final sugar level must be at least 35g/l but most are 50–80g/l. The wines are not allowed to be released before 1 March following the harvest. At alcohol levels between 7% and 8.5%, this sparkling wine presents the essence of bubbly grapey Muscat, with floral and peachy aromas balanced by delicate mountain freshness. The best 100% Muscats show incredible purity and real depth of flavour; those that include some Clairette (a maximum of 25% is allowed) generally have a touch more acidity and less depth.

The first rosé Clairette de Die wines were released in summer 2017 from the 2016 base wines, but the AOC was revoked for rosé in 2018 (see Diois) so only two vintages were made – and even these are not officially allowed to be sold. I have tasted a few samples, which varied in colour from the palest salmon orangey-pink to a more vibrant pink; some producers used maceration for the red grapes; others blended in some still red wine. The best samples combined grapey fruit from the Muscat with the typical red fruit aromas of Gamay (up to 10% permitted); these are very obvious Muscat-based wines with a little less freshness than Bugey Cerdon, and with softer grapey flavours. It remains to be seen how this style will develop, if indeed it is given the chance to do so, but semi-sweet sparkling rosé made in this way is gaining popularity across France and is even made elsewhere in the French Alps, as Vin de France.

Ancestral method producers such as Domaine Raspail keep the wines in tank at temperatures close to freezing point for long periods.