Chapter 4

Butchered on the Bridge 1527

In Tudor England, committing murder was not always a hindrance to scaling the social ladder. And none advanced further after the calculated killing of a man than William Herbert, who went on to become the Earl of Pembroke and one of the richest men in the land. Herbert was nothing if not a survivor, arguably getting away with not just one murder but two, and then gaining the favour of four monarchs including Mary I, despite initially backing her opponent’s bid for the throne.

Herbert’s origins did not give much hint that he would eventually rise to become so powerful. His father, Sir Richard Herbert, from Ewyas, Herefordshire, was the illegitimate son of a former Earl of Pembroke, also called William Herbert. Known as Black William, the Earl had backed the Yorkist cause in the War of the Roses and been executed by the Lancastrians in 1469. His grandson, William, was one of perhaps as many as ten children, born in about 1506. As a younger son of one of the members of the lesser gentry, he does not seem to have had much of an education, remaining illiterate to his dying day. Even as a member of the Privy Council in the reign of Mary, he could only scrawl his initials in capital letters. The seventeenth century chronicler John Aubrey described Herbert as ‘strong sett, but bony, reddish favoured, of a sharp eye’ and ‘stern look’. He also claims that he was a ‘mad fighting young fellow’ and relates that in his youth Herbert entered the service of a relative, the Earl of Worcester. Herbert was certainly a loose cannon and his hotheaded nature was soon to show itself.

On midsummer’s eve 1527, there were a great number of Welshmen in the city of Bristol, or Bristowe as it was then known. One of these was William Herbert, then in his early twenties. No doubt drink was taken as midsummer was an important occasion for celebration in Tudor times marked by bonfires, marches and pageants. Things got out of hand and there was some kind of affray between the Welshmen and the watchmen, an incident serious enough to merit mention in the city’s chronicles.

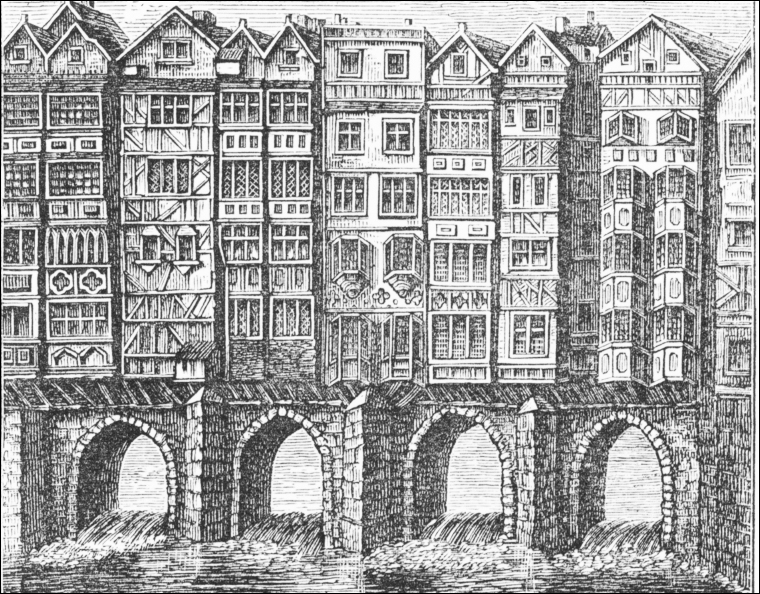

A killing on the crossing. Bristol Bridge as it would have looked in the sixteenth century. (Copyright Look and Learn)

On 25 July, the mayor and some other city dignitaries were returning from watching a wrestling match in the city, a popular Tudor spectacle with wrestlers from the West Country considered the most skilled. The party then crossed Bristol Bridge, which spanned the River Avon and had given the city its name (Brycgstow meaning place of the bridge in Anglo-Saxon). At this time the bridge would have been lined with houses, just like London Bridge.

It was here that William Herbert, along with a group of young companions chose to confront them. It was a very public location and one from which it was difficult to escape, suggesting that some premeditation had gone into what was to follow.

Herbert’s group was at least twenty strong, presumably outnumbering the older Bristolians. Among them were his step-brother, Thomas Bawdrip, also from Wales, Thomas Herbert from Mitchel Troy in Monmouthshire and another man with the same name who had also been in service of the Earl of Worcester. Joining this group was Walter Whitney, also of Mitchel Troy. These four ‘gentlemen’ were backed up by the yeomen David Williams from Chepstow and William Morgan from Cardiff along with a mariner named Lewis Ball and Walter Gurney, also from Chepstow and Cardiff respectively. There was one local man among them, John Herbert. Although he was living in Bristol it appears that he was originally from Wales too.

Whether William Herbert and his crew had the mercer William Vaughan in mind as a specific target, or just planned to cause trouble with some of the more important men in the town, we’ll never know. Vaughan was an important man in the city and had been sheriff in 1516. He himself had a Welsh background – his family were originally from Cardigan. While there may have been some old issue of contention between him and the group of menacing men on the bridge, Bristol had a large Welsh population at the time and his roots were probably mere coincidence. It may have been that Vaughan simply tried to push past the rowdy young Welshmen, but Aubrey suggests that Herbert resisted arrest, perhaps for something that had happened on Midsummer Eve. Whatever the circumstances, offence was taken by Herbert and the others for ‘want of some respect in complement’ from Vaughan. The enraged Herbert, along with at least six of his accomplices, brandished their swords and Vaughan ended up suffering a bad wound on the right side of his head.

Leaving Vaughan in a pool of blood, the leading culprits then fled through the city gates and into the marshland that then surrounded much of the old city. They were heading for Lewis Ball’s boat, which was waiting for them. A contemporary account suggests that Herbert and the others then set course for Wales and ‘escaped cleare away in a boate with the tide without any hurt done to them’. On 2 August, Vaughan died from his injuries and what had been an assault now became a murder. An inquest was opened by the Bristol coroner and two days later the matter was brought before local magistrates. Herbert, in his absence, was indicted as one of the wanted men.

While the suspects for Vaughan’s murder were long gone, his wife Joan was not about to let the matter lie. Realising that more muscle would be needed if they were ever going to be caught, she made an appeal to the court of the King’s Bench at Westminster. The original coroner’s report and indictment were brought before the King’s Bench in October 1528 but nothing more seems to have been done to attempt to apprehend the culprits or give Joan any form of redress at this time.

Meanwhile, Herbert is thought to have fled to France. Aubrey says that ‘he betooke himself into the army where he shewed so much courage, and readinesse of witt in conduct’ that he came to the attention of the French king, Francis I, who is alleged to have written to Henry VIII highlighting his good conduct.

On 1 September, 1529, seemingly out of the blue, William Herbert along with both Thomas Herberts, as well as John Herbert were granted a royal pardon for Vaughan’s death. The King’s Bench was told to ‘molest them no more’ and on 28 October, now back in England, they presented themselves before the court where the case against them was dismissed. It is probable that the Herberts had agreed to pay Joan some compensation for the death of her husband. Official records show that the ‘parties were agreed’.

Why Henry should favour a relatively lowly fellow like Herbert in such a case is a puzzle. Perhaps it was simply because Herbert’s family had served his own well. Herbert’s father had been a gentleman usher to Henry VII and had apparently been knighted by Henry VIII towards the end of his life. There’s evidence that some of the others involved in Vaughan’s killing, including Thomas Bawdrip and William Morgan, were not pardoned and proceedings continued against them. Herbert, however, soon got a job in service to the king.

Four years after his rampage in Bristol, Herbert’s quick-tempered nature caused him to come to the attention of the courts once again. In 1531, he was brought up, along with his brother George, and two other men including his servant Richard Lewis, over a fatal assault carried out in London. Again the victim was a Welshman, Richard ap Ieuan ap Jenkyn. Sadly, further details of the case are scant, but if Jenkyn’s death was the result of another dust up in the street it is likely that Herbert claimed self-defence and that his royal connections meant that, once again, he got away with it.

Ironically it was his very fighting abilities that Henry probably valued in Herbert. Indeed, tradition has it that the king was impressed by Herbert’s sword fighting skills when he once observed him showing off outside Whitehall Palace. Herbert must have had some charm too; at court he met Anne Parr and the couple were married in 1538. Anne was a woman much better educated than Herbert and it seems an unlikely match, but in an era when it was easy to lose one’s head by choosing the wrong faction, Anne shared a common trait with Herbert. She was also a survivor and in fact both William and Anne continued to retain royal favour throughout their lives. Anne, described as ‘a most faithful wife, a woman of the greatest piety and discretion’ had the unusual distinction of acting as lady-in-waiting to all of the king’s six wives – no mean feat.

Herbert’s success at court soon brought him riches and in the early 1540s he acquired the lands belonging to Wilton Abbey in Wiltshire where he set up home, building a grand house. His positon was strengthened further when Henry married Anne’s sister, Catherine Parr in 1543. Herbert, know knighted, was also distinguishing himself on the battlefield fighting for Henry in France during the campaign of 1544. He became keeper of Baynard’s Castle in London and owner of Cardiff Castle too. Under Edward VI his influence grew as he helped put down a rebellion in the West Country and he became a privy councillor. More land came his way and he was made the Earl of Pembroke in 1551.

Herbert’s fortunes might have faltered after he married off his eldest son Henry to Lady Catherine Grey, the sister of Lady Jane Grey. When Lady Jane briefly found herself on the throne Pembroke, inclined to Protestantism, initially appeared to back her claim to the English crown. But he was ever the tactician and when Mary gained the upper hand in her bid to be queen he switched sides, throwing Lady Catherine out of his house and getting the marriage between her and Henry annulled. Despite his political manoeuvring, Pembroke’s taste for a bit of action had not deserted him in later life as he vowed that, ‘eyther this sword shall make Mary Quene, or Ile lose my life.’

He was soon to prove his worth to the new regime by helping to quash Wyatt’s rebellion which briefly threatened the capital in 1554 and was still leading troops for Mary’s army in 1557. He continued serving on the Privy Council into Elizabeth I’s reign. Somewhat surprisingly, the Earl died in his bed, at Hampton Court, in 1570 and was buried in St Paul’s Cathedral.