Chapter 9

Butchered During a Game of Backgammon 1551

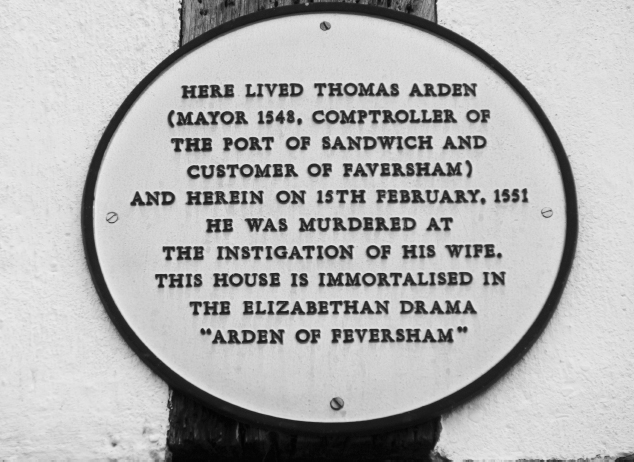

There is a half-timbered house that stands on the corner of Abbey Street and Abbey Place in Faversham, Kent, which at first glance appears to be just another fine example of the many impressive historic buildings that line the ancient thoroughfares of this small town. Yet this higgledy-piggledy property, which dates back more than 500 years, is somewhat taller than the others nearby and retains a melancholy air even on a sunny day; its upper storeys leaning out menacingly over the road below. The sullen appearance of what is known today as ‘Arden House’ takes on a more chilling dimension when you take a closer look at its street-side wall where there is a small plaque. It recalls the location’s dark and infamous past, revealing why the building has deserved special attention in the annals of this humble market town. For it was within these very walls that the house’s former owner, one Thomas Arden, was gruesomely murdered on the evening of 15 February, 1551.

Given its sordid nature, the Arden case sent shockwaves through the nation at the time. Indeed, the spellbinding story surrounding Arden’s death was still proving gripping decades later when the celebrated play Arden of Faversham, was written based upon this real-life thriller, possibly by William Shakespeare himself. The case would continue to be a subject of fascination for balladeers, playwrights and historians for centuries to come.

The true story which provided the plot for Arden of Faversham did not need much elaboration for dramatic purposes. The play’s main elements were very much based on cold, hard facts. And the real-life cast list might have been made for the stage. Indeed Raphael Holinshed found the Arden story so enticing that he gave it special attention in his famous Chronicles, a tome in which other murders of ‘ordinary’ folk are sometimes mentioned, but rarely dwelt upon. Yet of the Arden case he said, ‘The which murder, for the horribleness thereof … I have thought good to set it forth somewhat at large …’

The murder of Thomas Arden in 1551, from a woodcut in the 1592 edition of the play Arden of Faversham. (Copyright Look and Learn/Peter Jackson Collection)

By the time Thomas Arden met his end he was a successful and wealthy man. He was of a ‘tall and comely personage’ and may, originally, have been from Norwich, where it is thought he was born in 1508 into a family with a mercantile background. However, his later riches were built up following the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII. In the 1530s, Arden was a clerk working on transactions involving monastic property. He was in the employment of Sir Edward North, who would later become Chancellor of the Augmentations, in charge of redistributing confiscated church lands. Arden also worked for Sir Thomas Cheyne, who was Warden of the Cinque Ports and probably thanks to his influence he would go on to become a successful local customs official. Arden also used his knowledge and connections to snap up lands belonging to the former Benedictine abbey in Faversham. These included today’s Arden House, which had originally been the abbey’s guest-house and, in the sixteenth century, would have stood next to the abbey’s complex’s outer gateway. By the 1540s, Arden was an important player among the leading men of Faversham. He became an alderman and, in 1548, for a short time the town’s mayor.

In about 1537, Arden married a younger woman, Alice Brigandine, the daughter of a navy captain, who had become Sir Edward North’s stepdaughter. According to Holinshed, Alice was, ‘tall and well favoured of shape and countenance.’ The Faversham historian Patricia Hyde has put the age difference between Arden and Alice at about thirteen years, reckoning that Arden was about forty-three at the time of his death and Alice was roughly thirty. The couple may also have had a daughter together called Margaret.

At some point, the discontented Alice fell for the charms of a tailor and servant of Sir Edward North, called Thomas Morsby, a much younger man than her spouse. Alice and Morsby began an affair. At one point their relationship faltered but Alice, keen to rekindle the romance, sent Morsby a pair of silver dice as a love token, via Adam Fowle, who lived at the Fleur de Lis inn near her house.

Arden, it seems, had discovered what was going on between his wife and Morsby, but turned a blind eye. One of the earliest accounts of the murder, taken from the Wardmote Book of Faversham (essentially the official town records) tells us that Morsby was subsequently not only kept in their house, but that Alice fed him ‘with delicate meats’ and bought him ‘sumptuous apparel.’ Holinshed tells us that this state of affairs went on for some time, but that Arden put up with the shenanigans going on under his nose as he did not wish to fall out with his wife or her friends. Perhaps, most importantly, he feared falling out of favour with the powerful Sir Edward North. At any rate Arden was, so Holinshed records, ‘contented to wink at her filthy disorder.’

Eventually, however, the affair was not enough for Alice who wanted Arden out of the way so that she could marry Morsby. Holinshed says that she, ‘at length, inflamed in love with Mosbie, and loathing her husband, wished and after practised the means how to hasten his end.’

Arden was far from popular in Faversham. The ease with which he had accumulated so much land in the town had attracted the ire of other leading local figures. According to Holinshed, he had even cheated a widow out of the land where his dead body would eventually be found. Arden’s avarice finally got the better of him when he was said to have arranged for the upcoming St Valentine’s Fair to be held entirely on his own land, rather than letting the rest of the town in on the financial rewards. It was the last straw for other local dignitaries who, in December 1550, booted him out of his local offices, disenfranchising him completely.

Perhaps Arden’s unpopularity was one reason why his wife found it relatively easy to draw others into her dastardly plans for his downfall. In fact, she would later try and convince Morsby to join the murder plot on the basis that no-one would care about Arden’s death or make ‘anie great inquirie for them that should dispatch him.’

Alice’s initial attempt to do away with her husband involved poison, which she got with the help of a painter, William Blackbourne. This ploy had failed, according to Holinshed, as Arden simply threw up the potion and recovered. Now Alice managed to inveigle others into her web of intrigue. First she targeted a tailor, John Green, who had been involved in a local property dispute with her husband. Alice promised Green ten pounds if he could come up with a way of getting rid of her husband.

Soon, Green made a journey up from Faversham to Gravesend and took a local goldsmith by the name of George Bradshaw with him for company. On the way, near Rochester, they happened to bump into a well-known villain known as Black Will, from Calais, with whom Bradshaw had once served in the army on the continent. Green invited the ‘terrible cruell ruffian’ who was armed with a sword to sup with them and later hired him to kill Arden. He immediately wrote to Alice saying: ‘We have got a man for our purpose.’ Meanwhile Green also managed to recruit one of Arden’s own disgruntled servants, Michael Saunderson, into the conspiracy. While Arden was up in London on business, Green convinced Saunderson to leave the doors of the property where he was staying unbolted so Black Will could sneak in and murder him there. But Saunderson got cold feet, fearing he too would be killed and so the plan failed. On two more occasions, Black Will and a side-kick called Losebagg (George Shakebag in Holinshed) lay in wait for Arden in the countryside as their target went about his business, but they were again thwarted in their quest, by one obstacle or another.

Morsby, who was not yet persuaded that murder was the right course of action, now offered to pick a fight with Arden at the St Valentine’s Fair, presumably with the hope that Arden would die in the affray or challenge him to a duel. But he and Alice decided that this wouldn’t work since Arden had always remained phlegmatic when Morsby had tried to goad him in the past.

Alice now arranged a secret conference of the conspirators at the house of Morsby’s sister, Cecily Pounder, which was near her own home. In attendance were Morsby, Pounder, John Green, Black Will and Losebagg, Michael Saunderson and a maid (perhaps the Elizabeth Stafford mentioned in the Wardmote Book). They discussed how best to do away with Arden once and for all. At first, Morsby refused to be a part of the scheme and ‘in a furie floong awaie’ making his way to the Fleur de Lis inn where he often lodged. Alice sent a messenger after Morsby urging him to return, which he eventually did. Holinshed says that, ‘at his comming backe she fell downe upon his knees to him and besought him to go through with the matter as if he loved her he would be content to do.’ Finally she convinced him to take part.

That evening, at about seven o’clock, while Arden was out on business, Alice sent away most of the servants at their home – apart from those who were in on the plot. When the coast was clear, Black Will was ushered into the house and concealed in a ‘closet’ at the end of the parlour. When Arden returned home, Morsby met him on the doorstep and Arden asked him if dinner was ready. Morsby told him that it wasn’t and the two agreed to play a few games of backgammon in the parlour. The Tudor form of the game was then known as ‘playing at tables’ and was extremely popular.

Holinshed’s account of the murder has Arden sitting down in the parlour at the gaming table, with his back to the closet where Black Will was hiding. Michael Saunderson now stood behind Arden with a candle watching the game, further throwing a shadow on to the adjoining room where Black Will lay waiting for a signal. The conspirators had agreed on a verbal cue to let the hired assassin know that it was his moment to attack.

After a little while Morsby said to Arden: ‘Now may I take you sir if I will.’

‘Take me?’ Replied Arden studying the board curiously, ‘Which way?’

Suddenly Black Will appeared. The Wardmote Book tells us that he, ‘came with a napkin in his hand, and sodenlye came behind the said Ardern’s back, threw the said napkin over his hedd and face, and strangled him.’ Now Morsby got in on the act and, stepping towards Arden struck him ‘with a taylor’s great pressing iron upon the scull to the braine.’ Holinshed tells us that the iron weighed fourteen pounds and that after he had been struck with it Arden ‘fell downe, and gave a great grone.’ According to The Wardmote Book, Morsby then ‘immediately drew out his dagger, which was great and broad, and therewith cut the said Ardern’s throat.’

In Holinshed’s version, Arden was carried out to the counting house but was not yet dead and gave another groan. It was Black Will, not Morsby, who set about him with a blade, gashing Arden in the face. He ‘killed him out of hand.’ Black Will then looted Arden’s body taking, ‘the monie out of his purse and the rings from his fingers’ before demanding his fee too. Alice paid the assassin his ten pounds and Black Will left. Then she returned to her husband’s body and herself gave it seven or eight ‘pricks’ with a knife for good measure. The Wardmote Book has a slightly different version in which Black Will got his pay-off at Cecily Pounder’s house.

The murderous party now set about covering their tracks, cleaning the house of blood. But they do not seem to have given much consideration over what they were going to do with Arden’s body. The Wardmote Book tells us that they bore the corpse into a meadow adjoining the back of Arden’s garden. Here it appears to have been unceremoniously dumped – probably with the hope that his murder would be put down to some stranger attending the fair. Holinshed’s account reveals that Saunderson, Pounder, a maid and Arden’s daughter were those that carried the body into the field and that as they did so it began to snow. They then discovered they had forgotten the garden gate key and had to go back for it. Finally they laid Arden ‘down on his back straight in his night-gown, with his slippers on’ and left him in the long grass.

Once they had returned to the house and the other servants were summoned back to it, Alice had the gumption to entertain some visiting businessmen, pretending that Arden was simply late home. As time went on she made a show of getting worried about his whereabouts and, later that evening, sent entreaties around the town asking where her husband might be.

Later that night a search was launched, led by the new mayor himself. Unsurprisingly it wasn’t long before Arden’s body was found by a grocer called Prune, who apparently simply stumbled across the corpse in the gloom. Arden was quickly judged to have been ‘thoroughly dead’. Thanks to the snow, which the hapless murderers hadn’t counted on, the search party ‘espied certeine footsteps…betwixt the place where he laie and the garden doore.’

The mayor and his men immediately went to Arden’s house and quizzed both Alice and her servants. Whether or not his peers liked Arden, Alice had been sorely mistaken in thinking that they would not bother to probe his death. Given the cack-handedness of the crime, the mayor and the other men now had no choice but to find out what had happened. At first, Alice and her accomplices denied any knowledge of the murder. But the investigators not only discovered tell-tale blood and hair at the scene but the knife which had been used to kill Arden, as well as a bloodied cloth in the ‘tub’. Being presented with these items Alice knew that the game was up and confessed. She and the other members of the household who had helped her were promptly put in prison. Alice does not seem to have hesitated in implicating her own lover. That very night, Morsby was picked up at the Fleur de Lis inn where he was found in bed. In the room there was more incriminating evidence in the form of his hose and purse which was ‘stained with some of Master Arden’s bloud.’ He too confessed and was put behind bars awaiting a specially convened court.

The trial of Alice and her co-conspirators took place just weeks later at the very abbey hall that Arden had recently bought. Here they were ‘adjudged to dye’.

Alice was burned at the stake in nearby Canterbury on 14 March, 1551. The fate of the others was equally uncompromising. Elizabeth Stafford was burned at the stake too, in Faversham. Morsby was hanged at Smithfield in London along with his sister, while Michael Saunderson’s sentence was to be ‘drawn and hanged in chains within the liberties of Faversham’. George Bradshaw, despite pleading no knowledge of the conspiracy (probably with some justification) was nevertheless hanged in chains at Canterbury. Meanwhile something of a national manhunt was launched to find the other conspirators.

Finally, in July 1551, John Green was tracked down in Cornwall and returned to Faversham where he was hanged. Both Black Will and the mysterious Losebagg remained at large having presumably fled back to the continent. Holinshed reports that Black Will was arrested in 1553 and later ‘burned on a scaffold’ at Flushing in the Netherlands (modern day Vlissingen). William Blackbourne, the painter, seems to have remained at large. Adam Fowle, the innkeeper at the Fluer de Lis, was at first implicated and taken in shackles to London, but later released. No more mention is made of Alice’s daughter and her possible involvement.

Arden’s house in Faversham as is is today.

The intense drama of the murder was caught in a woodcut included in the frontispiece to Arden of Faversham, which emerged in 1592. It shows the very act itself, with Black Will strangling Arden while Alice hovers in the background with a dagger. The play itself fleshed out the characters of Alice and Arden, but the bones of the story were drawn from the facts. Debate still rages as to whether Shakespeare really did write it – Thomas Kyd and Christopher Marlowe have also been put forward as candidates. It was certainly written by an adept author, who had probably read Holinshed’s account of the murder. The case was never forgotten in Faversham and local legend has it that, for two years after the terrible event, the grass would not grow on the spot where Arden’s dead body was found.

Plaque recording the murder at Arden’s House.