Chapter 25

Who Killed Christopher Marlowe? 1593

While William Shakespeare is, today, a household name across the globe the poet and playwright Christopher Marlowe, born in the same year as his fellow writer, is less well known. Possessed of a talent arguably equal to his Elizabethan counterpart, Marlowe’s most famous work, Doctor Faustus, tells the story of a man who sells his soul to the Devil. It was the author’s own double life, working in secret for the government while he penned the odd masterpiece, that has caused his sudden and violent death, at the age of just twenty-nine, to be shrouded in mystery and the subject of heated debate ever since.

‘Kit’ Marlowe worked his way up from a modest background. Born in 1564 at Canterbury in Kent he was the son of a shoemaker who shone from childhood, winning a scholarship to the King’s School in the city and going on to study at Corpus Christi college, Cambridge. Over the centuries, he has earned a reputation as a hell-raiser. Certainly, as his literary career took off with the success of his great work Tamburlaine the Great, Marlowe seems to have followed a decidedly different and shadier path to Shakespeare.

We know for certain that from an early age he was in the queen’s pay, probably having been recruited as a spy whilst a student and serving as part of the notorious intelligence network employed by Elizabeth’s principal secretary, Sir Francis Walsingham. When, in 1587, there was some doubt raised by the college officials about the awarding of Marlowe’s MA, due to long absences (as much as thirty two weeks in one year) a letter from the Privy Council was sent to the authorities at Cambridge insisting that the degree should be conferred in the light of his ‘good service’ to the queen and alluded to secret ‘affaires’ on ‘matters touching the benefit of his country’. During the next decade Marlowe would turn up on the continent, almost certainly doing the government’s bidding. His lavish spending habits also suggested that this was someone who had a source of income beyond that of a budding playwright.

Marlowe was a tough sort who never shied away from a punch up. In September 1589 he was living in Norton Folgate, part of Shoreditch in East London near the capital’s main theatres. One afternoon Marlowe was found to be fighting in Hog Lane with a 26-year-old innkeeper’s son, William Bradley. Marlowe’s friend, the poet Thomas Watson, who’d had previous run-ins with Bradley, intervened, using his sword. Bradley died in the melee when Watson thrust his blade six inches into the other man’s chest, killing him. Both Marlowe and Watson were initially arrested on suspicion of murder and thrown into Newgate prison. Marlowe soon got bail and was, that December, acquitted. Watson was soon released too. In May 1592 Marlowe would get into trouble with the law again, for assaulting two constables in Holywell lane.

A year later he would himself be a victim. Marlowe’s grisly death, on 30 May, 1593, was as dramatic as anything in his plays. It has often been asserted that he was killed as the result of a tavern brawl arising from a trivial dispute. He was actually at a private house in Deptford, to the South East of London, run by a woman called Eleanor Bull, who hired the place out for meetings and meals. Here Marlowe had arranged to meet three other men at about 10am and spent most of the day in their company, dining, drinking, playing backgammon and walking in the garden. The official coroner’s report, only unearthed in 1925, records that the others present were Robert Poley, Ingram Frizer and Nicholas Skeres. According to the inquest, that evening after supper, Marlowe was lying on a bed when there was some kind of dispute about the bill described, in the parlance of the day, as the ‘recknynge’. Frizer was sitting at a table and facing away from Marlowe, wedged between the other two men. Erupting with fury Marlowe suddenly dashed at him. Snatching the dagger ‘which was secured at his back’ Marlowe then set about Frizer’s head giving him two wounds. The men present would attest that in the ensuing scuffle Frizer somehow wrestled back the dagger from Marlowe and stabbed him over the right eye. According to the inquest Marlowe collapsed, dying instantly. Frizer’s actions were deemed to have been in self-defence and he was soon pardoned. Marlowe’s body was buried locally, just a day after his death.

The rudimentary nature of the official inquiry into the killing left many questions unanswered. Could Marlowe have been overpowered by Frizer on his own? As we have seen, this was a man who knew how to handle himself in a fight. Would he really have died so quickly from the wounds described? Medical experts doubt it. Many commentators have concluded that the inquest does not offer up satisfactory evidence that Marlowe’s death was a case of self-defence and conclude that Marlowe was in fact murdered, with a whole host of different conspiracy theories arising as to what really happened and who ordered the killing.

The starting point for any notion that Marlowe’s death was not an accident is the chequered characters of Marlowe’s companions that day. Marlowe, we can be sure, had worked as a spy. And all three of the others had suspiciously shadowy backgrounds. Poley was a known government agent who worked as courier to destinations on the continent. He had also been a double agent who had helped thwart the Babington Plot, a scheme to assassinate Elizabeth in 1586. He once admitted that he would gladly perjure himself than say anything that would do him harm. Skeres was also a part time spy as well as a con-man and thief. Frizer was a servant, known for his dodgy dealings, in the employment of Thomas Walsingham, Marlowe’s patron. If ever there was a trio capable of a murder and covering it up, this was it.

Also key to any murder theory are the mysterious events that led up to Marlowe’s death. A year earlier Marlowe had been arrested over a counterfeiting scandal while in the Netherlands, accused by another shadowy figure called Richard Baines, with whom he was sharing lodgings. Baines was probably a spy too. It’s possible that Marlowe may have been using the coinage to bribe Catholics for information. Interestingly no further action was taken against him in London.

On 12 May, 1593, Thomas Kyd, a fellow playwright and ex roommate of Marlowe’s in London, had been arrested in an investigation into ‘divers lewd and mutinous libels’ which had been posted around London, some signed ‘Tamburlaine’. Heretical tracts were found in his lodgings and under torture he had said that they belonged to Marlowe. There had, in fact, been growing rumours of Marlowe’s supposed atheism. In late May a letter from his old enemy, Richard Baines, arrived at Court alleging that Marlowe had scorned God’s word on many occasions.

By 18 May, 1593, a warrant had already been issued for Marlowe’s arrest and two days later he attended the Privy Council for questioning. At this point he was bailed and merely told to attend upon them, regularly, until otherwise notified and not imprisoned. At the time Marlowe was staying with his literary patron Thomas Walsingham, the nephew of the deceased Sir Francis, at his home in Scadbury, Kent, possibly in an attempt to avoid the plague which had broken out again in London. Marlowe must have been a worried man at this stage. If proven, the charges of atheism and blasphemy could have seen him hanged, disembowelled whilst still alive and then drawn and quartered.

This series of events, quickly followed by Marlowe’s demise on 30 May, have given rise to the idea that he was the target of a political assassination involving the powerful figures of the day who wanted to keep him quiet because he simply knew too much. If he was brought in for torture and trial he might divulge some of his many secrets. One theory involves Sir Walter Raleigh, who Marlowe is believed to have befriended. Raleigh was involved with the so called School of Night, a group dabbling with the ideas of atheism. Could Raleigh, or those close to him, have been worried that Marlowe, would expose them? Another idea links Skeres to the Earl of Essex, that favourite of Elizabeth, with the suggestion that he wanted to convince Marlowe to turn evidence against Raleigh. Other potential VIP culprits who have been forwarded include Lord Burghley, the Lord Treasurer; and his son Sir Robert Cecil, who are said to have been worried that Marlowe might expose their own heretical views. Eleanor Bull, the owner of the house where Marlowe died is thought to have been related, albeit it remotely, to Burghley. There have also been allegations that the inquest jurors and coroner could have been nobbled.

The problem with all these suggestions, apart from a lack of any convincing documentary evidence, is that ordering Marlowe’s death in such a way was risky and surely done in a manner that was more complicated than necessary. Marlowe could have easily been dispatched less publicly.

There are some even wilder theories. There is the outlandish idea that Thomas’s Walsingham’s wife Audrey was jealous of the close relationship of her husband with Marlowe, who was possibly homosexual, and arranged the murder herself. Another suggests that Marlowe didn’t die at all, and that he colluded with his fellow spies to fake his own death with his body substituted for another recently executed man. Some, who subscribe to this view, even propose that Marlowe was the true author of the plays attributed to Shakespeare. A staged murder seems an elaborate way for someone like Marlowe to disappear and simply too outlandish given the simple facts known.

Of course Marlowe might have been murdered in a simple row about money. Yet, even for someone who had a reputation for getting involved in sudden and fatal brawls it does seem simply too coincidental that Marlowe’s death should occur at such a convenient moment, surrounded as he was by fellow masters of the dark arts of espionage. Their murky pasts beg the question as to why they were meeting with Marlowe that day. Perhaps these fellow spies themselves were worried about what Marlowe might reveal about them to the authorities. It is possible that they had spent the day looking for assurances from Marlowe but had already decided to kill him if they didn’t get them. Poley, Skeres and Frizer could easily have acted alone and then simply agreed on a story and stuck to it when giving their evidence. The messy events of the 30th have all the hallmarks of a crime carried out by a small coterie of ruthless men, rather than an execution ordered from high profile figures.

Of course, we will never know for sure whether Marlowe was intentionally murdered or not. But we can be pretty certain that had he lived he would have gone on to create more great plays. Most of his works were published after his death and received critical acclaim. Had he continued to write he would surely now be a literary figure with the stature to rival Shakespeare in the public consciousness. Indeed the famous bard himself appeared to allude to the manner of Marlowe’s death in his play As You Like It, written a few years later which includes the lines:

‘When a man’s verses cannot be understood, nor a man’s good wit seconded with the forward child, understanding, it strikes a man more dead than a great reckoning in a little room.’

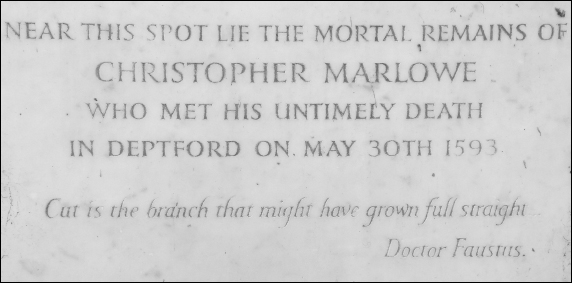

Above: The church of St Nicholas’, Deptford, the last resting place of the playwright, Christopher Marlowe, who suffered a sudden and mysterious death as reported by a plaque (top) in the graveyard. (Copyright James Moore)