British Commander of the Mediterranean Fleet, Andrew Browne Cunningham.

Adrian Warburton. Few pilots can have appeared so unpromising, yet from Malta he swiftly developed into one of the best reconnaissance pilots in the RAF.

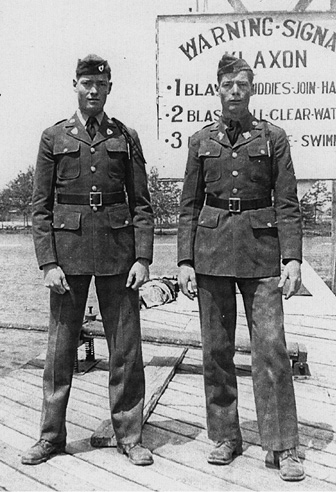

General Richard O’Connor (left), whose tiny Western Desert Force routed the Italians, and his C-in-C, General Sir Archibald Wavell.

Maresciallo Rodolfo Graziani, who understood that his Italian forces were ill-trained and -equipped to take the offensive.

In Libya, in Greece and in East Africa columns of Italian POWs became a common site. These are just some of the 133,000 captured during Operation COMPASS.

Indian troops in East Africa. Most British troops in the Middle East theatre were from India and the Dominions, which made geographical good sense.

Italian 105/28 field guns, dating from 1913. Rusting versions of these were given to Sergio Fabbri on his posting to Tripoli.

General Rommel, who reached Libya in February 1941.

A German and an Italian share a smoke. Most Germans had little more than contempt for their Axis allies.

Hermann Balck (centre), in his Panzer Mk III in Greece in April 1941.

The Operations Room at Derby House, Liverpool, HQ of the Royal Navy Western Approaches and the hub of an increasingly sophisticated shipping and anti-submarine warfare operation.

The open bridge of a British destroyer. Once the invasion threat was over, convoy protection increased significantly.

Otto Kretschmer was one of the most successful U-boat aces, but he was captured in March 1941. Two others, Günter Prien and Joachim Schepke, were killed that same month.

Erich Topp, another of the pre-war U-boat force.

The Bowles twins, Henry and Tom, at Fort Benning in 1940.

Kit inspection at Fort Benning. The US Army was still tiny and poorly equipped in 1940.

Hajo Herrmann, whose unauthorized bombing of Piraeus harbour was stunningly successful.

A wrecked British Blenheim in Greece.

British forces on the retreat again. Most British troops were safely evacuated, but, as at Dunkirk, much of their equipment was left behind.

General John Kennedy, the British Director of Military Operations.

Stanley Christopherson (centre), with fellow Sherwood Rangers at Tobruk.

A German soldier points to a map of Tobruk, which was surrounded and besieged.

An Italian poster attempting to put a gloss on the loss of East Africa, centrepiece of Mussolini’s pre-war empire. It promises a return and victory.

Bill Knudsen, giant of the US car industry, was brought in by the President to help kick-start US rearmament.

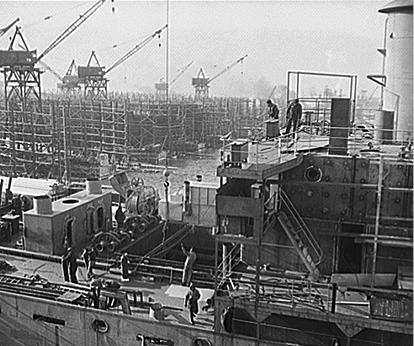

Liberty ships under construction, designed by Cyril Thompson in the UK and adapted for production in the US. Construction king Henry Kaiser managed to build two new shipyards on either side of the US in just five months.

Oliver Lyttelton, brought into government by Churchill, visits a British factory. ‘Steel not flesh’ was one of Britain’s overriding strategies for war.

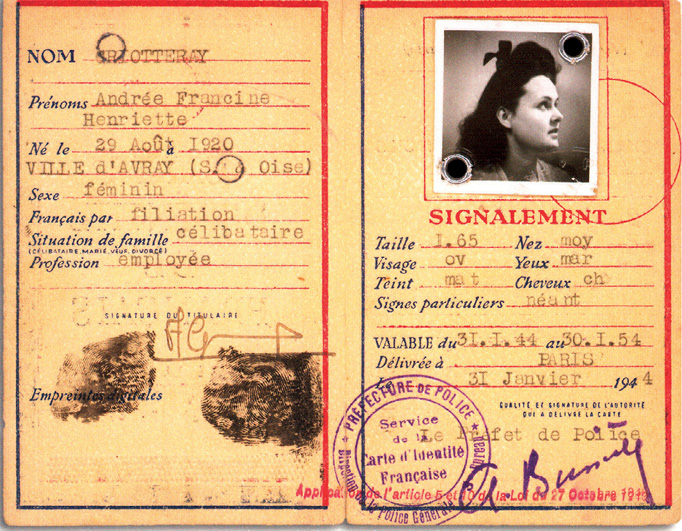

The ID card of Andrée Griotteray, the young Parisienne working in French police headquarters.

Freddie Knoller and family in Vienna in happier times before the war. Freddie is sitting with his beloved cello.

Firefighters tackle a blaze in London. The Blitz began in September 1940 and continued until May 1941. The damage was considerable but not sufficient to seriously affect Britain’s war effort.

Hitler with his generals. The Führer’s meddling and micro-managing of military operations was disastrous for Germany and often made no strategic sense.

General Bernard Freyberg VC. His courage could not be doubted, but he had been over-promoted and his misjudgement on Crete helped lose the island.

German Fallschirmjäger dropping on Crete as a Ju52 falls in flames.

The evacuation of Crete cost the Mediterranean Fleet dear. Here HMS Jackal comes under attack.