Industrial Potential

‘THE VIRTUAL ENTRY into the war of the United States at England’s side,’ wrote General Thomas in June 1941, ‘has resulted in all probability that what lies ahead is an economic war against Germany of indefinite length.’ Certainly, Thomas was not alone within the Third Reich in fearing the lurking threat of the USA; Hitler was also very aware of it. Back in the 1920s, when the USA had been Germany’s saviour, there had been every reason to hope that America and Germany would be economic and industrial allies for the foreseeable future, but, after Munich, Roosevelt’s rhetoric against the Nazis had left Germans in no doubt where his sympathies lay. Since the changes in the US Neutrality Act and the growing armaments production of the USA on behalf of Britain, the threat from America had grown alarmingly, no matter that US polls still showed there was little appetite for war.

This was just another reason why Hitler needed to win the war swiftly. It was also why Britain continued to fight – the USA, whose military strength was only growing, would have that all-important springboard from which to attack the Greater Reich. And not only was the United States vast, with access to the kind of resources Nazi Germany could only dream about, but it had the right conditions in which to build up military strength too. ‘The Americans can manufacture in peace,’ Feldmarschall Milch would tell a gathering of German industrialists. ‘They have enough to eat, they have enough workers, with still over five million unemployed, and they do not suffer air raids. American war industry is magnificently organized by a man who really knows his business, Mr Knudsen of General Motors.’

Compared with the chaos and personality clashes of the German armaments industry – and nowhere was this more evident than in the Luftwaffe – it was true that US rearmament suffered few of the hindrances that beset German industry, yet in June 1941 Bill Knudsen might have argued that he still had problems a-plenty. No one could doubt America’s rearmament potential, but a year on from leaving his position at GM and answering the President’s call, Knudsen was still struggling to ensure that potential was realized.

The problems had really begun to emerge following his deal with the US car manufacturers to make aircraft the previous autumn. In many circles in Washington and throughout the media, Knudsen was lambasted for allowing big business to scoop up most of the largest defence contracts. No matter how much Knudsen pointed out that it was those biggest companies that had the power and wherewithal to see those contracts through, and no matter how often he argued that there were still plenty of jobs for smaller subcontractors, the criticisms persisted.

Knudsen was, of course, looking at the situation with a purely businessman’s hat on; capitalism had served the American car industry well, and he had been given a brief to increase armaments production exponentially. He could take the criticism – he cared not a fig for politics – but whether the President could was another matter. Another gripe was that the car makers were still making motor vehicles for commercial sale, while also taking on war contracts. This, it was argued, was surely outrageously greedy and typical of fat-cat big businesses – and the criticism was certainly a concern to the President, who called Knudsen in to explain why civilian production was continuing when massed war production was of such urgent importance and the car manufacturers had been given millions of dollars to carry them out.

Knudsen explained. The key was to keep production in the plants going. If civilian production was shut down, the plants would stop producing anything for months. ‘If they are shut down for months,’ he told FDR, ‘the toolmakers will scatter.’ And if they did, it would be very hard to get them back swiftly again. What he was proposing was this: to bury the automobile manufacturers under defence orders – to the tune of three times as much as they could make with their existing facilities. This would keep them busy and force them to expand their facilities. And as their facilities expanded, so they would be able to keep their toolmakers. The government could force the automobile makers to stop manufacturing civilian automobiles, but not until the new facilities were in place. Successfully forcing them to switch to war manufacturing could only happen if there was continuity of production in their plants.

Roosevelt accepted these arguments; after all, it was for precisely this kind of knowledge of the industry that Knudsen had been hired in the first place. However, it was clear that the National Defense Advisory Commission was not working; its brief was too woolly, its authority too undefined. In December, the NDAC had been shut down and replaced with the Office of Production Management (OPM). Knudsen was appointed its Director General alongside Sidney Hillman, who had also served on the NDAC. Knudsen, Roosevelt announced, would lead American business, while Hillman would head up American labour. The OPM would also be a four-man board with Stimson and Knox, the Secretaries for War and the Navy, joining Knudsen and Hillman. To all concerned apart from Roosevelt, it felt like a bit of a fudge, but at least Knudsen was now working to a legal position, unlike his role with the NDAC, which had never been given any formal authority as such.

In the months that followed, the US rearmament commitments grew and grew. Lend-Lease did not help, because suddenly the British were ordering even more, for which the capacity somehow had to be found. Knudsen reckoned British orders were adding 60 per cent more man-hours to the original US war production programme. Suddenly, they were looking at orders worth $150 billion, yet Congress’s defence authorization for the following year remained just $10 billion. The truth was, no one, not even Bill Knudsen, knew what American business could achieve, so in the early summer of 1941 these vast numbers of contracts and dizzying figures really were just a lot of numbers on pieces of paper.

One thing, however, was certain: American potential would not be realized if the labour unions continued to agitate in the way they had begun to do. Roosevelt had repeatedly called for unity of purpose, but the American unions were coming to the fore, and the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, in which it was decreed there should be a maximum forty-hour week, had only just come into being in October 1940, just as the demand came for massively increased productivity. The unions were keen to protect this privilege. ‘The hard difficulty now,’ commented the Saturday Evening Post, ‘is to reconcile our newly conceived national labor policy with the imperatives of an unlimited defense program.’ Added to this was the CIO, the Congress of Industrial Organizations, dominated by Communists, who resented US involvement in war production as they viewed the conflict as a bourgeois struggle from which the US should steer clear. Yet not all unions were dominated by the Communists and, in fact, the CIO’s new president, Philip Murray, was not even a Communist; his prime concern was to secure a greater share of the defence-boom profits for those in the union and to ensure they were protected as and when the boom was over. At any rate, one way of making these gripes and concerns heard was to go on strike. The first to do so were workers at the Vultee aircraft plant in San Diego in November 1940, and the action then spread like wildfire. By March, there were some fifteen strikes at aircraft factories alone. This loss of man-hours was beginning to badly affect the US’s ability to rearm – Knudsen reckoned it was slowing war production by as much as 25 per cent. ‘When I realize that the hours lost might produce engines and bombers, guns, tanks, or ships,’ he told the National Press Club, ‘then I hope for guidance – divine guidance – to get some sense into all our heads and to realize this thing must stop.’ Sidney Hillman, the OPM labour head, seemed powerless to do anything about it, and the situation was made worse by John L. Lewis, leader of the United Mine Workers (UMW) union, who had a personal vendetta against Hillman, was a virulent isolationist, and encouraged miners to repeatedly strike over issues of both pay and union shop. Hillman and Knudsen suggested the creation of a national defence mediation board, to which the President agreed, but it made no difference. Nor was the President prepared to take any radical action; instead, the glut of strikes was simply allowed to run its course.

Despite this, armament production was rising, and, more to the point, the huge increase in the production of machine tools, a process that took at least around nine months, was about to take effect. With these crucial weapons of any industrial process in place, production could at last accelerate, even with ongoing labour issues.

Union strikes were not affecting all corners of war production, however. Henry Kaiser’s workers, for example, showed no inclination to strike; rather, workers were queuing up to sign on. Labourers from some sixteen different craft unions applied for work and were quickly taken on – which was one of the reasons why Kaiser had been able to confound predictions over the speed with which his new shipyard at Richmond, California, would be up and running. By calling upon many of the key men who had helped build his large road and dam projects and understood how to think big, he completed the foundations for the new yard not in the six months predicted, but in just three weeks. Gargantuan amounts of mud and silt were dredged and replaced by rock and gravel, and then the concrete was added, at the rate of a staggering 700 concrete piles a day. Seven slipways were built, each with a large assembly area at the head where sections of ship could be prefabricated and then lifted by giant cranes into position.

Cyril Thompson had returned to the States – this time flying – to see the work in progress and had been amazed. ‘Progress in California was astonishing,’ he noted. ‘Kaiser went about the task in a big way.’ In Portland, the second new shipyard was being built almost as quickly as that at Richmond. Incredibly, the first keel was laid in the Todd–Kaiser yard on 14 April 1941, while the first at Portland was put down on 24 May. The transformation at both places – from nothing to bustling shipyard – was truly staggering and a vindication of Thompson’s choice of Kaiser as the right man to fulfil Britain’s urgent demand for more shipping.

On this second trip to America, Thompson had also brought with him the blueprints for his latest merchant ship design, and, with Admiralty approval, these were given to Gibbs & Cox, a firm of naval architects. The project was given to William Gibbs, one of the firm’s partners, and it was hoped initially that under his guidance the firm would fill the gap caused by the lack of design and drawing offices at the two new yards, but very quickly they took on the added role of purchasing all necessary materials needed to build both the ships and their engines. Under the guidance of Thompson, they were to produce an entirely new set of plans, based on the original ship design but modified for welding rather than riveting and to suit US ship-building practices. Far greater detail was needed than was ever expected in a British shipyard. ‘In other words,’ said Thompson, ‘nothing whatever was left to be arranged on the ship. This practice saved endless time and argument in the shipyards, where local surveyors were responsible only for seeing that all plans were exactly followed.’

By the time Thompson flew back to Britain during the first week of June, he had already seen the first Liberty ships emerging at both Richmond and Portland. These vessels, created by harnessing British and American design, expertise and construction acumen in almost perfect co-operation, were an achievement that could not have been realized anywhere else in the world. And since shipping, as much as any other factor, was shaping Britain’s ability to fight the war, and preventing Germany’s defeat of its most dangerous enemy, the free world had reason to thank Cyril Thompson, William Gibbs and Henry Kaiser, especially.

Far across the oceans, at GHQ in Cairo, the British were once again able to temper bad news with good. Crete had fallen, but the more important island of Malta had been enjoying a respite from the Luftwaffe and had been causing havoc to Axis convoys bound for Tripoli. The coup in Iraq had also been successfully quelled and a new pro-British government formed in Baghdad. The Greek government had formed in exile in Cairo, and fresh supplies, including more aircraft, had reached Egypt. Greece and Crete had been lost, but the British position in the Middle East was reasonably safe in the short term, at any rate.

However, one serious further threat was now emerging, and that was from Vichy-controlled Syria, where the governor, Général Henri Dentz, had been entertaining German agents who had come to Syria in the hope of securing some Luftwaffe air bases. Général de Gaulle had got wind of this news and requested facilities, which were granted from London, to visit Cairo and see his representative there, Général Georges Catroux. With General Edward Spears in tow, de Gaulle reached Egypt only to learn from Catroux that Syria was ready to cast aside Vichy and fly the Cross of Lorraine, but only if Free French troops arrived in force. Currently, though, there were some 30,000 Vichy French forces in the Levant; de Gaulle could call on just 6,000. This meant he needed British help. On 15 April, in Cairo, de Gaulle, with Spears’s support, then appealed to Anthony Eden, who was broadly sympathetic but pointed out that it could not afford to fail; therefore a force had to be put together that could ensure success. When he put this to the Chiefs of Staff, however, they ruled out such a venture absolutely. Wavell was equally dogmatic. ‘If de Gaulle’s people do anything,’ he told Spears, ‘it must be a success.’

For de Gaulle, this was more than frustrating. He both wanted and needed his Free French movement to gather momentum, and despite the failure at Dakar the forces flying his banner had kept hold of their successes in Central Africa. Free French units had fought alongside the British in East Africa too, while back in December they had successfully attacked an Italian outpost in southern Libya. From Chad, de Gaulle had ordered one of his best lieutenants, Général Philippe Leclerc, to march on the oasis at Kufra, which, after a month’s siege, had been taken along with 300 Italian prisoners. On the other hand, de Gaulle’s offer to send troops to fight alongside the British in Greece had been declined, while his approach to Weygand, still in Algeria, had been ignored. What’s more, he was extremely frustrated at being beholden to the British, all of whom seemed to him to be patronizing and unwilling to share his vision for the Free French. The person he found most annoying of all was General Spears; the two wanted the same ends but increasingly were struggling to rub along together.

Rashid Ali al-Gaylani’s coup, however, changed everything, although it should have changed nothing. German intentions in Syria and Iraq were speculative and, following the losses on Crete, unrealistic, but the swathe of dynamic German successes had clouded British judgement; even John Kennedy, equally unaware of German plans for the Soviet Union, was in favour of an immediate move into Syria, partly to stop German interference there, but also because RAF possession of Syrian airfields would counteract any Luftwaffe presence on Crete; Alexandria was equidistant between the two.

Yet, in reality, not even the Führer was prepared to divert more resources to the Middle East with BARBAROSSA around the corner. Furthermore, Hitler was so appalled by the casualties to the Fallschirmjäger that he had even announced that, henceforth, there would be no more airborne assaults. However, since the British only knew about the German build-up of forces in the East but no details of any offensive plan, the security threat from Vichy Syria now appeared to be growing, not lessening – or, at least, it seemed that way to Churchill and the Chiefs of Staff back in London. De Gaulle had moved to Brazzaville in Central Africa in a fit of anti-British pique and had threatened to pull out Général Catroux, his representative in Palestine. On 14 May, Churchill signalled to de Gaulle, urging him to keep Général Catroux in Palestine and inviting him to return to Cairo. A joint assault on Vichy Syria was suddenly very much on the cards. De Gaulle’s reply, his first and only one in English, was succinct:

1. Thank you.

2. Catroux remains in Palestine.

3. I shall go to Cairo soon.

4. You will win the war.

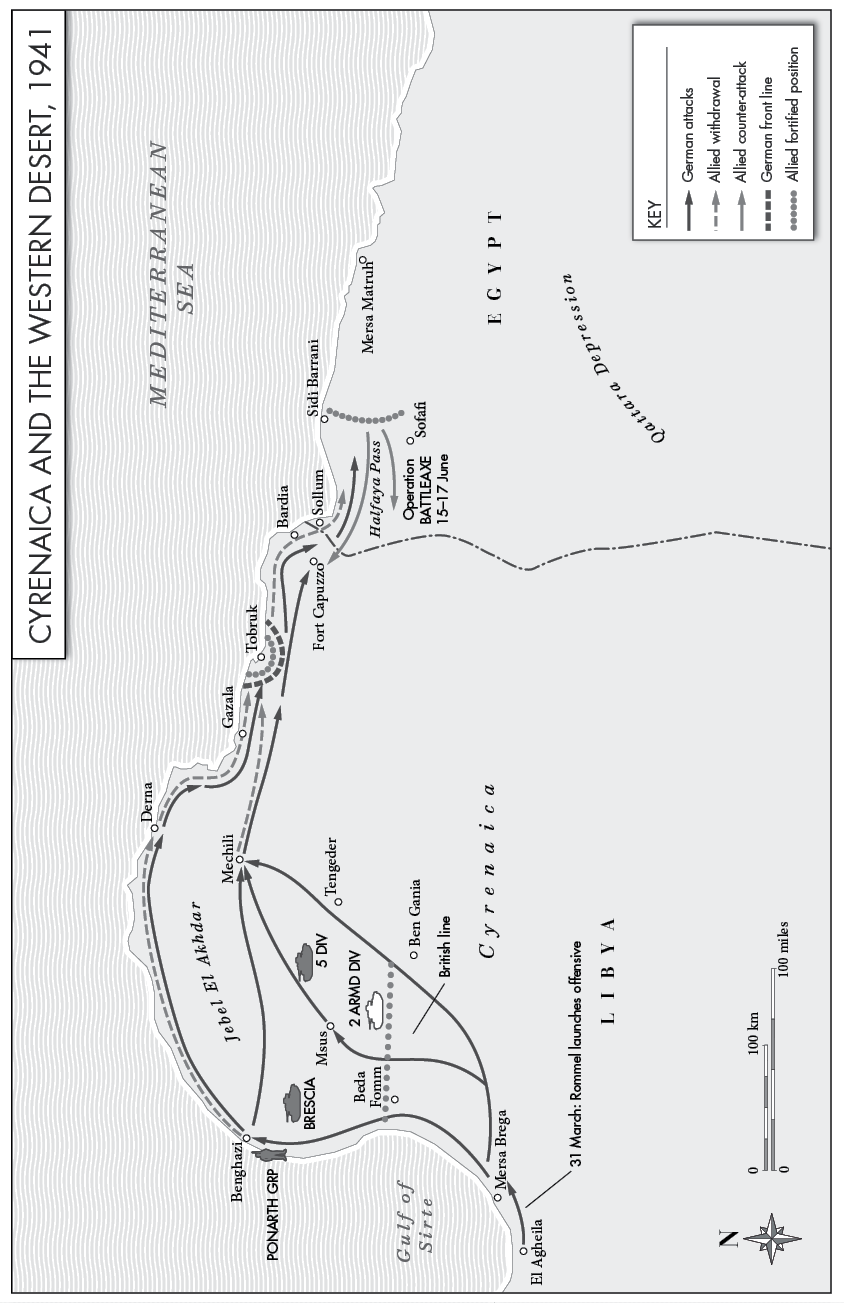

Général Catroux, who had remained in Palestine, then insisted he had intelligence that the Vichy French were about to move into Lebanon and hand over the rest of Syria to the Germans. Turkish troops, meanwhile, were reported to be moving towards the Syrian border. Catroux’s information was nonsense, however, and, needless to say, Wavell, took a dim view of both Churchill’s latest interference and London’s willingness to gobble up the French general’s claims. Wavell’s reluctance to send troops to Syria was compounded by the imminence of Operation BATTLEAXE, his latest attempt to push back Rommel and relieve Tobruk, which had similarly been pushed on to him by Churchill. For any joint British and Free French operation in Syria to have a chance of success, Wavell would have to scrape back together the forces he had sent into Iraq and also pull more from BATTLEAXE.

His objections fell on deaf ears, however. The attack on Syria, codenamed EXPORTER, was on, and would launch on 8 June. BATTLEAXE, meanwhile, would begin on 15 June, just a week later. The timings were hardly complementary, and had Wavell had a better relationship with Churchill, the obvious and right course of action would have been to postpone the latter. Even without the Syrian venture, British forces in the Western Desert were not ready for battle. It was true that the Tiger convoy of 240 tanks had been safely delivered, but they had arrived in bad shape, having been damaged by careless stowage, and in any case 7th Armoured Division needed training time to get used to the new, fast Crusader tanks.

However, by the kind of juggling at which Wavell was by now becoming expert, he managed to get a force for Syria in place which included most of 7th Australian Division, a 5th Indian Brigade group, fresh back from East Africa, some Free French forces and a few units of armour and cavalry. Admiral Cunningham promised some offshore naval support too.

The assault on Syria opened with a proclamation broadcast by Catroux and leaflet drops, and with the Australians advancing up the coast and the Indian Brigade heading north from Transjordan into central southern Syria. The Free French then took up the advance from the Indians and soon found themselves facing the bitter realities of civil war as they came up against Vichy French troops to the south of Damascus. Meanwhile, the Australians were also facing dogged resistance as they tried to cross the Litani River north of Tyre. With a battalion of Commandos, they managed to eventually get across the river, but, five days into the campaign, it was clear reinforcements were going to be needed. Despite Free French intelligence to the contrary, the Vichy defenders apparently had no intention of tamely giving up.

Wavell’s attack in the Western Desert began, as planned, on 15 June, and was in essence an enlarged version of BREVITY a month earlier. Both sides were fairly evenly matched with a similar number of men, tanks and guns; attacking the Italians without a material advantage was one thing, but doing so against Rommel’s Afrikakorps was another. Nevertheless, British intelligence about German dispositions was pretty accurate – the Italians were keeping up the siege of Tobruk, Rommel’s 15. Panzerdivision was up at the Egyptian–Libyan border, while his second division, 5. Leichte Division, was further back resting and retraining. The key was going to be overrunning 15. Panzer immediately before 5. Leichte Division could enter the fray. Even so, that still only gave the British a two-to-one advantage at the Schwerpunkt, and the plan called for 4th Indian Division to do most of the head-on assault on 15. Panzer around Sollum and ‘Hellfire’ Pass, while 7th Armoured carried out another wide sweep to the south in an outflanking manoeuvre that was also intended to block 5. Leichte Division.

Sadly for the British, however, the plan was simply too ambitious. In three days of fighting, fortunes ebbed and swayed, but by the 17th the British were forced to break off the battle and withdraw to refit, leaving behind roughly half of the 200 tanks with which they had begun the fighting. The Germans had lost about half that number but were in no position to push the British any further. Once again, stalemate descended over the Western Desert.

For the soldiers involved, BATTLEAXE had once again been a battle of dizzying confusion. At the best of times, the desert was disorientating. Apart from the large escarpment overlooking Sollum and the coast, the land appeared flat; but this was deceptive. The horizon would appear short, but then would suddenly widen again as the top of an imperceptible ridge was reached. Distances were incredibly hard to judge in this vast, bleached and, in June, fearsomely hot landscape. For miles and miles there was nothing: no houses, no infrastructure, no obvious landmarks. The difference from fighting in France, for example, could not have been greater.

And once the fighting started, and sand was whipped up and the air filled with dust and smoke, orientation became even harder. As Albert Martin, still with 2nd Rifle Brigade, had learned, there was never really any discernible front line. ‘The reality,’ he noted, ‘was a series of battles taking place miles apart, with your own private conflict seemingly the only war going on at the time. Then your engagement was either completed or broken off and you were sent to lend support in an action taking place ten miles away.’ Because it was all so confusing, commanders necessarily resorted to the use of radio more frequently than they might otherwise have done, yet British radio traffic was too easily intercepted by the enemy, which meant the Germans were able to anticipate British moves and react accordingly.

Martin and his mates also discovered that after three days of intense desert fighting like this the mental and physical strain began to take its toll. The heat was blistering, which sapped energy, and combined with lack of sleep, physical exhaustion and lack of proper food and drink, meant they were no longer in any fit state either adequately to attack the enemy or properly to defend themselves.

‘The PM is gravely disappointed,’ noted Jock Colville at the news of the failure of BATTLEAXE, ‘as he had placed great hopes on this operation.’ So too was Stanley Christopherson and the rest of the Sherwood Rangers still in Tobruk; they had hoped to be relieved and to be heading back to Alexandria along the coast road. ‘We don’t seem to be able to give these Germans a crack,’ he noted. ‘It really is most disappointing . . . the general opinion is that we can’t win this war in under eighteen months or two years.’ At least, though, they were still confident the war would be won. In fact, no matter how many victories the Germans had recently chalked up, they still rather wondered how Germany could possibly hope to win. Sitting in their little besieged corner of Tobruk one evening, they had been eating supper and pondering German intentions. ‘We had a most interesting discussion,’ jotted Stanley Christopherson cheerfully, ‘trying to determine in our minds exactly what the war aims of Germany were now . . . She must realize that she can never completely conquer England, the Empire and America, even after many years of struggle.’

Had Hitler been a fly on the wall, he would have told the Sherwood Rangers what he told his senior commanders at the final conference before BARBAROSSA on 14 June. Germany would win by invading the Soviet Union and decisively beating the Red Army. Russia’s collapse, he assured them, would induce Britain to give in. There was absolutely no evidence to support this, and no reason whatsoever why Britain would even consider it in the short to medium term, but that was what Hitler told them and he was sticking to his guns.

Three vast army groups, each of a million men, were now lined up ready for the invasion, although, as with the invasion of France and the Low Countries, it was the thirty panzer and motorized divisions that would be leading the charge. Along with nearly 3,000 tanks, General von Schell had managed to muster around 600,000 motorized vehicles to support this vanguard. There were also 7,000 artillery pieces, which was fewer than for the attack on the West, and 2,252 combat-ready aircraft, compared with 2,589 the previous year.

There was also some sense of mission creep over what the objectives were for BARBAROSSA. The Führer had made it clear from the outset that it was about making the most of the Soviet Union’s economic, industrial and agricultural resources, while at the same time fulfilling his racial ideology. This meant turning north to secure the Baltic coastline and south into Ukraine. For Halder, however, the most important objective was Moscow, and striking quickly and capturing the capital was his prime goal. This was fraught with risk because it would mean driving a massive wedge through the heart of the Soviet Union, leaving German flanks very much more exposed than they ever had been in France. On the other hand, by turning north and south, they would be allowing the Russians a chance to fall back and protect the capital. However, since Hitler was even more powerful a military leader than he had been before the fall of France, Halder had been forced to acquiesce.

For the men now waiting to flow into the Soviet Union, the mood was mixed. Günther Sack, back from the Balkans and part of Army Group Centre, remained as unwavering in his zeal as ever. ‘My belief in God is still strong and unshakeable,’ he jotted, ‘and also my belief in Germany and my love for the Führer.’ But there was understandable apprehension too, although it was the war against Britain, not Russia, that was most on his mind. ‘What the near future will bring me is unclear,’ he added. ‘Probably, it will take me somewhere where we will confront the English as well. But then, the war will last many more years.’

Oberst Hermann Balck was also feeling contemplative. ‘We are at a decision point in the war,’ he noted in his journal. It worried him that the British were still in the Mediterranean – they would have to be driven out. And then there was the Soviet Union. At the beginning of June, he was still unaware that an invasion was imminent, but he was with Hitler in thinking a showdown with Russia was unavoidable and that the sooner it happened, the better. ‘Once Russia is subdued,’ he wrote, ‘an encirclement and blockade of Germany becomes impossible. And at that point we can ignore any ups or downs in the public opinion on the home front. We will have a free rein then to crush England.’

For Hans von Luck, the biggest apprehension was over the size of the Soviet Union, which was so vast as to be incomprehensible. ‘The Ural Mountains,’ he wrote, ‘which are nearly 2,000 miles away, were merely the end of the European part.’ Among his comrades, the earlier euphoria had given way to a more sober view. And would Germany be able to cope with a second front? Would Britain exploit the fact that the bulk of the German armed forces were now in the East? He was ready to do his duty, but he felt in a strange frame of mind. ‘We were not actually afraid,’ he wrote, ‘but neither were we sure what our attitude should be toward an opponent whose strength and potential were unknown to us, and whose mentality was completely alien.’

On the eve of BARBAROSSA, there were, then, several major question marks remaining: about the ongoing war with Britain, about how much plunder could realistically be taken from the Soviet Union, over whether Hitler’s or Halder’s strategy was the correct one, and whether German qualitative superiority was enough to smash the quantitative superiority of the Red Army. Finally, did the Germans have enough mechanized forces and air power to deliver the lightning crushing of the Russians that was so essential to German success?

BARBAROSSA was launched in the early dawn on 22 June.