What gives us that frisson of certitude, as in I'm right?

Neurologist Robert Burton has long wondered about precisely this feeling, as described in his brilliant, elegantly readable On Being Certain.2 A feeling of certainty, Burton muses, is important from an evolutionary perspective. How else can we quickly make a life-or-death decision such as which tree is best to climb to escape a hungry lion?

There are, in fact, disorders of certainty. Obsessive-compulsive disorder, for example, involves the inability to be certain. Did I really turn off the stove when I left? Some people can take certitude to self-righteous extremes, as with suicide bombers, those who kill doctors who perform abortions, or ecoterrorists.

Burton saw that even good intentions can go terribly wrong when people dig their heels in because they believe they are right. One of Burton's most frustrating memories concerned Dr. “X”—a prominent oncologist who was well-known for his aggressive approach to treatment of even the most terminal patients. Dr. X asked Dr. Burton to do a spinal tap on an elderly man with advanced widespread cancer. “He's not as mentally clear as he was yesterday,” said X. “Maybe he has an infection—meningitis, a brain abscess—something treatable.”3

As Burton recalls:

I've known Dr. X. for years and have no doubt about his clinical skills and his utter dedication to his patients. Medicine is his life; he's available 24/7, and, when all fails, he even attends his patients' funerals. And yet I dread working with him. Driven by a personal unshakeable ethic of what a good doctor must do for his patients, he wears his mission on his rolled-up sleeves, his full-steam-ahead attitude challenging and often shaming those of us who favor palliative care over prolongation of a life at any cost. He has the intense, uncompromising look of someone with a calling.

Upon entering the room, spinal tap tray in hand, I am confronted by the patient's family. “Please, no more,” they say in unison, backed up by the frail patient's silent nodding. “Could you talk with Dr. X, tell him that we're all in agreement.”

I page Dr. X and explain the family's wishes. “No, I want the spinal tap done now,” he says. “And don't try to tell me how to practice medicine. I know what's best for my patients.”

“Please,” the wife pleads, her hand gripping my arm. She'd overheard Dr. X on the phone. “I know that he cares, but it's not what we want.” But moments later Dr. X rushes in with his characteristic air of urgency, and explains why the test is necessary. No one really believes him, not the patient, not the family, and certainly not the nurse who turns away to hide her look of “how could you?” And yet, the family accedes. Even the patient agrees to the test, resigning himself to more poking and prodding, pain and suffering, in order not to offend his doctor. I, too, give in.

The spinal tap is difficult and painful, and reveals nothing treatable. The patient has a post-spinal tap headache that lasts until he lapses into coma and dies three days later. Afterwards, in talking with Dr. X, it's clear that he's learned nothing from this experience. “It could have been something; you can't know if you don't look. End of discussion.”4

But how and why do we feel that ineffable feeling we know as certainty? As it turns out, hidden from our active consciousness are underlying neural calculators—a “hidden layer”—that help us grapple with the reality that surrounds us. You might think of this hidden layer as a little like the chip that underlies a computer's computations. You may not know anything about the machine code and assembly language that underlies a computer figuring out the square root of 289. But you can apprehend the result—17.

As a consequence of the computations of your hidden layer, you can look at a face and instantly feel a sense of certainty about whether or not you've seen it before. Everyone's hidden layer is different, due to previous experiences, previous thoughts, genetics, and a multitude of other factors. As Burton points out, the hidden layer “is the anatomic crossroad where nature and nurture intersect and individual personalities emerge. It is why your red is not my red, your idea of beauty isn't mine, why eyewitnesses offer differing accounts of an accident or why we don't all put our money on the same roulette number.”5

But notice that the feeling of certainty we get—the feeling of I know that face!—is outside our conscious control. Like it or not, certainty is a feeling—an emotion—not a rational conclusion. That feeling can lead you astray—as when you say hello to an old friend and find you've surprised a complete stranger. “Without a doubt,” as Burton notes, “is nothing more than an involuntary sensation of a perfect match.”6

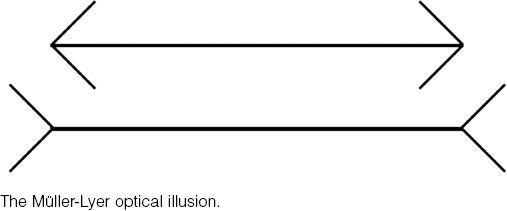

As an illustration of how rational, “objective” knowledge and “felt” knowledge can collide, Burton points toward the Müller-Lyer optical illusion. On the one hand, we can see objectively that the two horizontal lines are the same length. But yet, other unconscious factors scream a different certainty based on other visual cues. Indeed—there are different and conflicting ways of knowing.

This feeling of certainty springs, it seems, from the pleasure-reward parts of the brain—the same areas that are triggered by drugs such as heroin and cocaine. Our feeling of certainty is a sort of circuit breaker that “stops infinite ruminations and calms our fears of missing an unknown superior alternative. Such a switch can't be a thought or we would be back at the same problem. The simplest solution [is] a sensation that feels like a thought but isn't subject to thought's perpetual self-questioning.”7

But, as polymath science fiction writer David Brin observes, this feeling of certainty can feel so good that it can sometimes become an addiction. We can see this addiction firsthand in self-righteous people, who are keen to wallow in the wonderful feeling that they are right and their “opponents are deeply, despicably wrong. Or that [their] method of helping others is so purely motivated and correct that all criticism can be dismissed with a shrug, along with any contradicting evidence.”8 Good intentions don't somehow elevate us above this perceptual conundrum.

In fact, we often behave in an altruistic manner because we are certain that our actions are morally sound and will indeed help others. But no matter how we might think we have reasoned our way to a particular moral conviction, that conviction was arrived at subconsciously, through an emotional feeling.

This same set of conclusions applies to our feelings of certitude regarding our moral choices. “What feels like a conscious life-affirming moral choice—my life will have meaning if I help others—will be greatly influenced by the strength of an unconscious and involuntary mental sensation that tells me that this decision is ‘correct.’ It will be this same feeling that will tell you the ‘rightness’ of giving food to starving children in Somalia, doing every medical test imaginable on a clearly terminal patient, or bombing an Israeli school bus.”9

CERTITUDE AND DOING GOOD

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross wrote the seminal book On Death and Dying, which describes her theories of how people psychologically adjust to death. Her work was enormously valuable in opening a dialogue with dying patients that showed that contemplating and talking about death could be beneficial for everyone involved. But Kübler-Ross's devotion to helping others came at enormous cost. She provided “extraordinary care to her patients, often personally paying for ambulances, against medical advice, to transport dying children home for Christmas.”10 After founding—and funding—a healing center for the dying, she “obsessively devoted her time to her patients, becoming consumed by her work and essentially living at the healing centre so as to be available to her patients at all times.”11 She claimed she saw the ghosts of her patients, and she became deeply involved with psychic channeler and self-ordained minister Jay Barham. “He has so much integrity,” she said. “The truth does not need to be defended.”12

Time magazine described the unfolding scandal as follows:

Barham conducts group sessions where, he says, spirit entities materialize by cloning themselves from cells of his body. The entities are unusually interested in sex, sometimes pairing off the living participants for fondling or mutual masturbation. In private sessions women are selected for sexual intercourse with an entity. Participants in the sessions, many well-educated, if gullible, middle-class professionals, have had occasional doubts about the entities…. Four women in the group developed the same vaginal infection after visiting an entity on the same night. A few of the participants noticed that entities made the same mistakes in pronunciation (such as “excape” for escape) that Barham did. But most put aside their doubts. “I needed to believe,” admitted one woman in the group. “It was a sense of being loved unconditionally.”13

Kübler-Ross's faith in Barham is unshaken. A friend, Deanna Edwards, says she attended two darkroom sessions in hopes of changing the psychiatrist's mind about Barham. Edwards says she ripped masking tape from a light switch and flipped on the lights, revealing Jay Barham wearing only a turban. “I never heard such screaming,” says Edwards, who hastens to explain that it was not the sight of Barham that caused the alarm; the other participants believed that light destroyed an entity. Edwards was sure the demonstration would convince Kübler-Ross that Barham was a fraud. No such luck. “This man has more gifts than you have ever seen,” says Kübler-Ross. “He is probably the greatest healer that this country has.” The current furor does not appear to disturb her. Says she: “Many attempts have been made to discredit us. To respond to them would be like casting pearls to swine.”14

Kübler-Ross was as obsessed and certain about the importance of her work as she was about Barham's innocence. Kübler-Ross's husband finally became so disturbed that he gave her an ultimatum—she needed to choose either work or family. She “chose work, disappointing her husband and family and receiving a harsh judgement by the divorce court, which ruled against her in custody proceedings.”15

It is within that feeling of rightness that the problem nestles. As Burton concludes:

The strength of a moral decision can be seen, at least in part, as the synergistic action of unconscious cognition, involuntary feelings reflecting the rightness of this decision, and a powerful sense of pleasure in knowing that this decision is correct. It isn't in our nature to willfully abandon feelings of rightness and sense of purpose, especially when you add in the moral dimension of such actions making you “a good person.”

I cannot imagine a more powerful recipe for potential misguided “good behavior.” The only defense is the understanding that we can't know with any objective or even reasonable certainty that what we consider an act of altruism is actually of overall benefit to others.

For me, acting altruistically is like prescribing a medication. Believing that you are helping isn't enough. You must know, to the best of your ability, the potential risks as well as benefits. And you must understand that the package insert as to the worth of the medication (your altruistic act) was written by your biased unconscious, not by a scientific committee who has examined all the evidence.

Back to Dr. X. Despite many attempts on the part of other medical staff, Dr. X continued to his dying day working non-stop to help his patients—whether or not they wanted his help. No contrary or tempering advice sunk in. At his memorial service, I sat through an outpouring of poignant testimonials to his dedication and devotion. No one spoke for those patients who suffered from his well-meaning excesses. Years later, I remember Dr. X mainly for what he taught me about uncritical acceptance of believing that you “are doing good.”16

LEFT SIDE-RIGHT SIDE

Perhaps surprisingly, misplaced feelings of certitude fall right in line with research involving the differing roles of the brain's two hemispheres.

The two sides of your cerebrum are different. They are so different, in fact, that if the two were separated (as is occasionally done by slicing through the connecting tissue in epilepsy patients), they sometimes tussle over what they want. Roger Sperry, who won a Nobel Prize for his pioneering research in neuropsychology, found one of his patients “struggling to pull his pants up with his right hand while at the same time yanking them down with his left. Another assaulted his wife with his left hand while defending her with his right.”17 Truly it is as if we each have two completely independent minds fighting to control our body—two “wills,” as it were—although we always have only a single consciousness. (Interestingly, it is always the left hand that “misbehaves”—a telling reminder of the fact that the word sinister itself comes from the Latin word for left.)

What to make of all this? Wouldn't it be more logical, from an evolutionary perspective, for there to be a single, unified brain commanding our bodies?

As it turns out, right from the beginning of the animal kingdom, creatures have evolved to grapple with two simultaneous, highly demanding tasks. A bird, for example, must be able to simultaneously focus on the food in front of it, as well as warily scan to surroundings for danger. These different ways of seeing the world are tough to do at once—rather like patting your head and rubbing your tummy simultaneously. Specialized cerebral hemispheres seems to be the solution evolutionary processes have hit on, because it is widespread in vertebrates. And it must have developed very early on in evolutionary history, because animals from plovers to marmosets to humans specialize in the same way—left hemisphere for focused attention (pecking at food), right for breadth and flexibility of attention (keeping an eye out for hawks).18

As psychiatrist Ian McGilchrist notes in his masterpiece on the differing left and right hemispheres of the brain, The Master and His Emissary, this particular division of neural labor “has the related consequence that the right hemisphere sees things whole, and in their context, where the left hemisphere sees things abstracted from context, and broken into parts, from which it then reconstructs a ‘whole’; something very different. And it also turns out that the capacities that help us, as humans, form bonds, with others—empathy, emotional understanding, and so on—which involve a quite different kind of attention paid to the world, are largely right-hemisphere functions.”19

It's easy to discount brain-lateralization theories as so much pop psychology. But as McGilchrist's staggeringly erudite synthesis shows, there's real power in the theory. How we understand the world is a function of which hemisphere gains dominance—or whether the two reach an amicable balance. Or, in more unusual cases, whether one or the other hemisphere gains hyper-dominance.

Studies of split-brain patients, those who have suffered strokes, and those who have had one hemisphere or the other of their brain anesthetized all give us fascinating insight into the very different attributes of the two hemispheres. It seems that the right hemisphere is what gives us an understanding of what's going on out in the world (an expanded version of “watching out for hawks”). In a very real sense, then, the right hemisphere is in touch with reality. The information it collects is passed on to the left hemisphere. This second, “major” hemisphere (so called because it has the ace-in-the-hole powers of speech), is the one that specializes in focusing (“pecking at food”), dividing into categories, and viewing the world more abstractly. Patients with right-hemisphere strokes (which leave the left hemisphere intact) report a peculiar distancing from reality—their world seems flat, and the ability to empathize can disappear.20

Left to its own resources (that is, when disconnected for whatever reason from the right brain), the left brain is a blithely self-satisfied, upbeat Pollyanna that is perfectly willing to make up stories so as to maintain a sense of certitude. This explains the strange phenomenon whereby patients with right-hemisphere strokes that paralyze the left side of the body can refuse to believe there is anything wrong. Such patients will make up the most outlandish stories to explain why their left arm isn't moving. As McGilchrist observes, “Note that it is not just a blindness, a failure to see—it's a willful denial. Hoff and Pötzl describe a patient who demonstrates this beautifully: ‘On examination, when she is shown her left hand in the right visual field, she looks away and says ‘I don't see it.’ She spontaneously hides her left hand under the bedclothes or puts it behind her back. She never looks to the left, even when called from that side.’”21

As famed neurologist Vilayanur Ramachandran notes, these stroke patients show “an unbridled willingness to accept absurd ideas.”22 McGilchrist goes on to point out that left-hemisphere dominance seems characterized by “[d]enial, a tendency to conformism, a willingness to disregard the evidence, a habit of ducking responsibility, [and] a blindness to mere experience in the face of the overwhelming evidence of a theory …”23

Experiments where one side of the brain was anesthetized result in interesting conclusions.24 For example, if told

1. All trees sink in water;

2. Balsa is a tree.

3. Implied conclusion: Balsa wood sinks in water.

The subject with only an active right brain will point out that what he has been told seems to suggest that balsa wood sinks—but the reality is, it floats. The right brain, McGilchrist points out, appears to be the seat of our innate bullshit detector. But the patient with only an active left brain will insist that wood, most notably balsa wood, sinks—“that's what it says right here!”—real-world facts be damned.

Could deficits in the ability to dial down the influence of the left hemisphere account for some people's unwillingness to see facts that contravene their own perceptions? Could it also account for the almost outlandish stories some can believe—in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary—if it confirms their initial impressions?