Mike McGrath's disturbingly bad day started out normally.2 Not one for breakfast or lunch, he revved himself on coffee as he drove to one of the many sites he supervises in Rochester, New York—a collection of inpatient and outpatient mental health clinics and chemical dependency programs. McGrath's job involves dealing with quality of care, client risk management, recruitment and retention of staff-each of these tasks is far more demanding than the bland corporate phraseology would make it appear.

McGrath has been a practicing psychiatrist and forensic psychiatrist for over two decades. He is a general psychiatrist who treats anyone age eighteen or older. Over time, however, he's developed proficiency with chemical-dependent offenders and sex offenders, and he's acquired a subspecialty in forensic psychiatry—the application of clinical expertise to legal questions. This means that when prosecutors or defending attorneys are trying to determine whether someone is competent to stand trial, or scratching their heads trying to understand a defendant's state of mind at the time of a crime, McGrath is the kind of expert they turn to. As the years passed, McGrath has worked with and treated many victims of domestic violence; he has also forensi cally evaluated both abusers and their victims. When offered honoraria for occasional local presentations about psychiatric issues, he has always asked that the money be donated to a battered women's shelter.

McGrath seems like the prototypical WASP, but his graying ponytail whispers of nonconformity. He writes:

During my surgical residency I ran into a twenty-six-year-old Haitian girl who was employed as a unit clerk at the hospital. She had come to the USA at age seven with her younger sister to reunite with her mother who had emigrated years earlier. She had an associate's degree in finance and was working at the hospital for a few months where her mother was a nurse, trying to figure out what road in life to take next. I felt an immediate attraction to her, but she was so pretty I assumed she had several boyfriends. Slowly we got to know each other and I learned she had a five-year-old son and had come back from California (where she had been married and living for a few years) to make a new start. She was living at her mother's home in Brooklyn. The attraction between us grew and before long we were saying wacky things like “I love you.” Leslie and I got married in February 1986. I adopted her son a few years after we married and we have two daughters, one a first year law student and one a college graduate with a degree in history, trying to figure out what she wants to do, which I understand. Our son is an industrial engineer and he and his wife had a daughter—our first granddaughter—who was born on President Obama's inauguration day.

Between his wife, son, and daughters, McGrath is keenly aware of minority and gender issues—when pressed, he notes: “Just because I'm a white male doesn't mean that is my sole perspective on things.”

Perhaps because of the nature of his work, it's difficult to catch McGrath in a smile. Pictures reveal a man with no need to ingratiate himself to the camera. Indeed, when asked to describe himself as a forensic expert, McGrath writes, “I think the way I would describe myself is that I am an advocate for the truth and get very annoyed when I see others twisting it, regardless of the way it may play out.”

It was evening, as McGrath remembers it, when suddenly the crux of what he was researching struck him as having deep-rooted problems. It didn't seem right. It wasn't fair.

WHAT'S FAIR?

Even animals have a sense of fairness. Adult wolves, lions, and bears “play fair” with their cubs—keeping their claws and teeth in check as their tiny adversaries spring in mock menace. Monkeys will happily munch lettuce but will put on a monkey-pout if offered lettuce while a compatriot gets a juicy grape. It's not fair, their accusing eyes seem to say as they refuse the second-class treat.3

Unsurprisingly, our feelings of fairness arise through a complex tug and pull of neural music—blindingly fast synaptic rhythms and patterns that badger and chivy our brains into feelings of compassion for others in comparison with ourselves. But the neural music isn't the same for everyone. There's the rub.

If you grow up in a happy suburban home with a PTA mom and a dad who coaches Little League, you may stare at a picture of a broken-nosed, bloody woman and recoil in disgust. That's not fair, you think as you learn she was hospitalized because of her husband's Saturday night drunken outburst.

But if you grow up watching your mother being beaten every day by your father, you may not have the same reaction at all. The guys you hang around with may have seen the same patterns play out in their own families. Maybe you also got a good whipping when you did something wrong (and sometimes, even when you didn't). You and your brothers and sisters had some all-out clout wars to determine who reigned. Growing up like this, you are more likely to think a man beating a woman is normal behavior. After all, in your world, a woman has her place—how else are you going to keep her in line? And doesn't beating her show the depth of your feelings?

It's even more complicated, though. In some families, it's the dad who's beaten or emotionally abused. A child grows up thinking it's normal and fair to despise a weakling dad who never hits back—a man who instead drinks or takes drugs to strip away the pain.

Even more confusing, some children who have never been exposed to domestic violence engage in it, while some children raised in households with significant domestic violence grow up to be exceptional parents.

In the end, fairness isn't a perfect Platonic structure—like a sphere or cube—that lies outside us in some quintessential form. Instead, our own ideas of what fairness looks like are imperfectly woven into the very fabric of our brains through our lives and cultures. (The brain's two hemispheres seem to feel these effects in different ways—it is the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in particular that appears to underwrite our sense of justice.)4 Genes have a powerful effect, obviously, but those genes are physically influenced—turned on and off—by the environment. “Environment” also includes other people and how they treat us—in a word, culture.

Culture can change, of course. Just over a generation ago, as researcher Linda Mills points out in the book Violent Partners: “[D]omestic violence was considered a private matter. Some people felt that a man's home was his castle and that it was no one's business what went on there. Others assumed that the violence in most marriages was either provoked (and therefore deserved) or rare (and therefore something to be endured, like bad weather). Why intervene?”5

But by the early 1980s, American culture was shifting. Open minds heard the impassioned words of women who had long been disenfranchised. The women's movement was becoming a radical force to be reckoned with.

By and large, people care. We're fair. So long as it's not too big of an intellectual leap from the culture we've grown up with, we can be brought by both emotional and rational appeals to change our outlook if others suggest something is not fair.

But who decides what's fair?

BATTERED WOMAN SYNDROME

Shadows flickered that evening in Mike McGrath's study—pictures of his smiling daughters looked down from overloaded bookshelves. McGrath's study is a tribute to his professional and private interests: Honorary plaques share the walls with a musket and collection of ornamental swords so sweeping that a tangle of extras tussle for room in the corner. Usually, the study was simply a comfortably untidy hangout where McGrath could lose himself in his work. But tonight, as he was scrabbling through his research papers, he felt a creeping sense of unease.

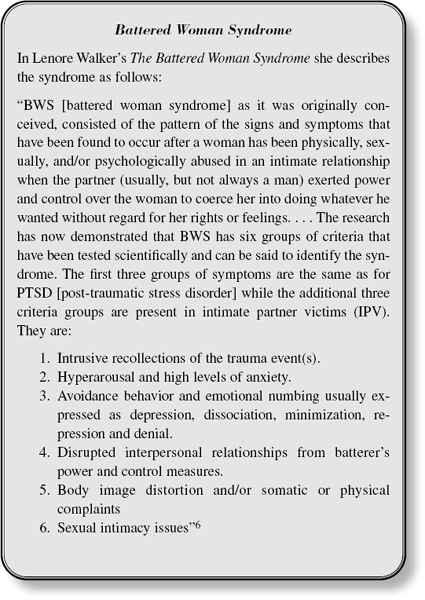

McGrath was reading Lenore Walker's The Battered Woman Syndrome, a classic for those who seek to understand the motives of women who stay in violent, abusive relationships. As a forensic psychiatrist, McGrath was keenly aware of the difficulties in psychiatric diagnosis of trauma syndromes. Indeed, that's why he'd been asked to write about battered woman syndrome for a new book, Forensic Victimology. (Since criminals have a discipline called criminology, it makes sense that there is also a field for victims called victimology.)

Walker's basic thesis implied that battered women are essentially normal—or at least were normal before the battering occurred.7 These unlucky women have simply fallen in with abusive men. McGrath had no initial beef with Walker's thesis, knowing from personal experience that not all women enter battering relationships due to psychopathology. What didn't sit well with McGrath, though, was the methodology and extent of her research. As far as he could see, there were no independent control groups in Walker's studies.8 How do we know, he asked himself, whether Walker's study subjects were similar to or different from non-battered women?9 Wouldn't Walker want to know that?

McGrath shifted in his chair, as much to realign his thinking as his posture, then skipped back on the page to reread Walker's explanation of her methods.

In conducting this research design, certain decisions were made that were appropriately influenced by the feminist perspective. For example, given the finite resources available, it was decided to sacrifice the traditional empirical experimental model, with a control group, for the quasiexperimental model using survey-type data collection. It was seen as more important to compare battered women to themselves than to a nonbattered control group. Comparing battered and nonbattered women implies looking for some deficit in the battered group, which can be interpreted as a perpetuation of the victim-blaming model.10

McGrath leaned back in his chair, looked up at the ceiling, then looked down again, dumbfounded.

In arcane, teasingly academic fashion, Walker was saying something extraordinary: that her findings related to battered women had never been compared to those of non-battered women. And possibly more important, those passages telegraphed that she had no intention of ever doing a study employing a standard control group—exactly the kind of research needed to demonstrate the validity of her claims.

She just doesn't think the rules apply to her, he realized.

As he began to burrow deeper, he began to see more. Walker's work, as it turned out, had never been replicated.11 And she claimed she couldn't compare her group with normal women, because in thirty years, she hadn't been able to find an equivalent group of some four hundred un-battered women.12 A psychologist might think, So what? If normal women were shown to be different from battered women, this still wouldn't get at the quality and accuracy of battered women's perceptions.

But that wasn't the point, McGrath realized. If the battered women sometimes carried a difference in their own personalities, then therapeutic efforts focused only on abusers might not repair the problem. If it took two to tango, with victims playing their own role in the dance—well, Walker's studies wouldn't reveal that, because Walker appeared to have started from the unproven assumption that battered women were different only because of the battering—otherwise they were basically normal. Therefore, the victim side of the equation could never be approached from a preventive angle.

Of course, McGrath realized, by wanting to understand whether there is pathology present in the victims as well as the abusers, there was always the danger of overfocusing on the negative qualities of the victim, which could not only oversimplify the problem but also turn it into an exercise in blaming the victim. After all, no matter how it's sliced, abuse is a slaughterhouse of the psyche. A woman (or man) can end up walking on eggshells trying to please a partner who can never be pleased. Such a spouse can be a Janus-headed nightmare—a publicly benign significant other who turns the spigot of emotional or physical abuse on behind closed doors. Regardless of how tangled the mess of blame and responsibility becomes, at some point, someone recognizes that he or she needs to get out of the situation. But escape is not a matter of snapping one's fingers and moving out—especially when children are involved.

How can these potential problems be avoided? McGrath wondered. How can the rigors of science help women understand what got them into a battering situation in the first place and how to avoid it in the future? A balanced approach that looked fairly at both partners was what was needed in Walker's research. But a balanced approach was not what she was providing.

Walker's approach isn't necessarily going to help battered women, McGrath realized. It was perfectly possible that an abusive man, for example, might be helped through therapy, but that the battered woman, who had no therapeutic attention devoted to her, might then move on to re-create the battering in a new relationship. (The “problem” for women in some abusive relationships, in fact, might be some of their nicest qualities—agreeableness, a trusting nature, enjoyment in helping others, and a desire to always look on the bright side.)

Ultimately, Walker's faulty scientific approach not only didn't address the whole issue, it might be creating a whole new slew of problems, because legislation in a number of states was based on Walker's approach. This meant prosecutors and defense lawyers had to take her assumptions about battered women, in some sense, as facts. To do otherwise courted appellate reversal.

In McGrath's analytical way, he slowly began to realize something more: everything he thought he knew about battered woman syndrome—a key aspect of litigation in murder trials involving battered women—was now suspect.