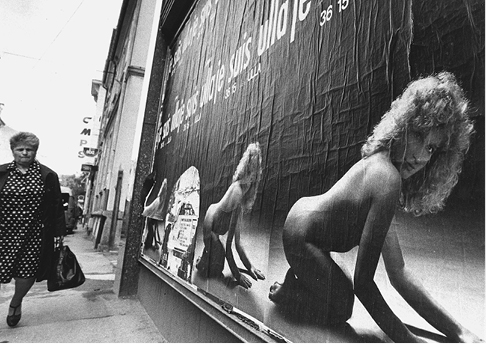

Figure 5.1 A woman walks by a billboard in Mulhouse advertising 3615 ULLA, one of the most famous messageries, August 1987. Source: Authors’ collection.

In the mid-1980s, computer geeks traveling to Paris were confronted with glimpses of a telematic future. By 1986, advertisements for Minitel services were ubiquitous on the highways and high streets of France. All along the dark, gloomy taxi ride from the airport to the city, colorful billboards implored drivers to tapez, or “type,” inscrutable alphanumeric sequences into their home terminals. Crossing the Porte de la Chapelle, one of Paris’ thirty-eight “doors,” a remnant of fortified Gallo-Roman communication networks, the visiting geek would see yet more Minitel advertisements plastered on the city walls. While some ads sported recognizable brand names, such as national newspaper Le Monde, others featured startlingly erotic photos of nude women and men, gonzo illustrations, and piercing neon graphics, all tagged by similarly mysterious strings: 3615 ALINE, 3615 CRAC, 3615 ENCORE, and 3615 ULLA. Further into the Latin Quarter where students, hipsters, and intellectuals crowded along the Boulevard Saint-Germain and the UGC Danton cinema was still playing Retour vers le Futur, the visitor would encounter a little newspaper kiosk with a towering poster trumpeting “3615 SM.” Our geek has found “le Minitel.”

These were the 1980s: appointments were made over landline calls, there were no pagers or cell phones, and yet advertisements for commercial online services pervaded the visual culture of the city. By the time writer Howard Rheingold arrived in Paris in the early 1990s, Minitel was fully domesticated, a bare fact of everyday life through the cities and towns of France.1 Billboard advertisements—as common in rural towns as metro cities—materialized the emerging online frontier. Unlike in the United States where online services operated largely out of sight of the general public, everyone living in France was peripherally aware of the network thanks to the omnipresence of Minitel advertising in print and public, on television and the radio. Indeed, even the most dedicated Minitel users spent more time staring at Minitel ads than sitting in front of their terminals. For while many people brought terminals into their homes, the high per minute cost of actually using Minitel precluded the kind of permanent connectivity that most of us enjoy today. In a very real sense, the cultural memory of Minitel is largely shaped by its representation in commercial advertising. Billboards and television ads enjoyed a pervasiveness that the actual consumption of services did not, and defined Minitel both in material and cultural terms.

Figure 5.1 A woman walks by a billboard in Mulhouse advertising 3615 ULLA, one of the most famous messageries, August 1987. Source: Authors’ collection.

The billboards that stuck in the memories of tourists and citizens alike were advertisements for the sexually explicit services, known locally as Minitel rose. With their libertine use of sexual innuendo and naked skin, the pink advertising made a strong impression on French society. In Rheingold’s account of the period, “the churches and many citizens looked on in horror” at the proliferation of rose imagery through the city.2 Surprisingly, however, a majority of private citizens and government officials took the pink services in stride—a surprisingly sexy quirk of the information society.

In spite of their memorable ads, however, the pink services were just one slice of a lively culture of entrepreneurship and commercial experimentation supported by the Minitel platform. With its built-in billing system and population of users, Télétel provided a generally low-risk environment—a primed pump—for would-be online service providers. Far from being an impediment to innovation, as it is often characterized, the State instead encouraged free enterprise by actively sharing its own taxpayer-supported research on human–computer interaction and online consumer behavior. The positive feedback loop in this two-sided market attracted a cohort of wild, young entrepreneurs who were poised to see a reliable stream of revenue in the short term—a key distinction from the more widely publicized dot-commers who floated on venture capital a decade later. The decentralized aspects of the architecture of the platform enabled service providers to experiment with a variety of business models, frequently anticipating models that would surface later as web services and mobile phone apps.

Within a few years, Minitel was deeply enmeshed within popular culture and public life in France. Over time, the thematic range of Minitel services expanded—from hobby sites and niche fetish communities to a variety of information databases and targeted business services—drawing more and more of the French population into the online world. This increasing integration of Minitel into quotidian French life was reflected in the lyrics of pop songs, plots of television dramas, and other ephemera that would otherwise not be seen as “techie” or “geeky.”

In this chapter, we explore the breadth of commercial services that were assembled atop the Minitel platform. In the first half of the chapter, consistent with the cultural memory of Minitel, we begin with a deep dive into the profoundly successful phenomenon known as Minitel rose. Not only were pink services adopted widely across French society, they provided a massive stream of revenue to traditional institutions—from the telephone company to major newspaper publishers. Without this novel financial opportunity, the media ecology of late twentieth-century France would have developed quite differently. In the second half of the chapter, we detail several notable Minitel-related businesses that represent the commercial diversity of the platform. From home automation and online banking to e-commerce and virtual assistants, many of the experiments taken up by Minitel entrepreneurs are only beginning to take hold on the web thirty years later.

In the hands of third-party developers and nonspecialist users, Minitel developed in ways that Télétel engineers and early advocates could not have anticipated. As sociologist André Lemos reflected in 1996, Minitel came to life, achieving a “technical vitalism” as a result of the unpredictable interaction between diverse social forces and new media technologies.3 The very existence of the messageries, or chat rooms, is the result of that vitalization process. The messageries’ founding myth attributes their appearance to a teenage boy nicknamed Big Panther, who, the story goes, used his TRS-80 to hack into the internal messaging system of Gretel, an experimental Minitel system run in the city of Strasbourg by Les Dernières Nouvelles d’Alsace beginning in 1981.4 The story was best told by Michel Landaret, manager of Gretel, at a wake in honor of Minitel in June 2012:

The first messagerie, the first chat, we set up in 1981, and of course it immediately went awry, as you could have guessed. How did it start? Simply put, someone hacked a system. You know, at the time, we weren’t concerned about hackers. So we had a menu that went 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and I set-up a .99, and of course someone found it [laughter]. Well at first it was cute, it was nice, one would use it to order croissants from the boulangerie, on Saturday night, for Sunday morning delivery, and then the first smutty moniker appeared. … it was Peggy La Cochonne.5

That first “smutty moniker” on Gretel presaged the subtle, bawdy humor and innuendo that would characterize much of the discourse around the pink Minitel. Peggy La Cochonne is a direct translation of the Muppet character Miss Piggy. In French, though, Peggy La Cochonne has a salacious connotation, as the word cochonne, literally “female pig,” is also a slang term for a promiscuous woman. The moniker thus suggested something a little naughty without coming right out and saying it.

Pleasure, play, sexuality, and anonymity swirled together on the new system, and there was no stopping the inflow of money. Landaret remarked, “[Minitel was] made on gaming and sex, as usual, just like all technological innovations, including the Internet.”6 Adult-oriented services were not cordoned off or marginalized; Minitel was infused with sexuality and innuendo. As Landaret wryly noted, “All messageries are pink.”7 Sexy chat may not have been part of the original plan for Minitel, and not everyone was happy about the emerging culture, but Télétel administrators did not want to stanch this new stream of revenue. Landaret remembers hearing conflicting messages from Minitel administrators. At a France Telecom conference, Direction générale des télécommunications (DGT) representatives admonished the gathered service providers, calling adult services an “abomination.” In private, however, DGT project lead Jean-Paul Maury displayed greater equanimity toward Minitel rose, reassuring Landaret: “but above all, do not stop, it is the only thing that brings in money.”8

And money, they brought. The Gretel messageries were used on average 22.08 hours per day, and one had to dial in repeatedly for 1.02 hours on average before actually being able to connect, as the lines were constantly busy. The record for the highest phone bill on Gretel (over a two-month billing cycle) was FF225,000. One Telic-Alcatel employee managed to spend 520 hours on the messagerie over a one-month period (which has 720 hours in total). The longest continuous messagerie activity by one user was 74 hours; someone finally noticed the incongruity of the situation, Landaret says, “and we had to send an ambulance.”9 Other entrepreneurs tell the same story. Daniel Hannaby, cofounder of 3615 SM, said, “I remember one person sending us a letter that she was asked by France Telecom a bill of 30,000 Francs; so it was a lot of money at the time, 30,000 Francs it was really huge. And so she was asking for us to reimburse but well, we couldn’t do that.”10 A 1986 study calculated that a small messagerie, averaging 150 hours of connection per day, would gross 173,250 francs per month—that is, over 2 million francs per year.11 It reported that in May and June 1986 only, 14 million calls were made to Télétel numbers for 1.7 million hours of total connection time, of which 70 percent was spent on messageries. Assuming these numbers are correct, at 61.60 francs per hour of connection charged to the end user, this would amount to 73.3 million francs for that two-month period for the messageries—averaging these numbers over twelve months, the entire messageries industry would have made 879.6 million francs for the year.

Starting shortly after the introduction of the kiosk system, and for several years thereafter, the high cost of Minitel to the user became a recurring theme in the popular press. Newspapers and magazines frequently published horror stories of humongous phone bills showing up out of the blue, either because the unsuspecting customer had not realized how much time they were spending, or how much money was charged per minute, or because children explored the new electronic frontiers while their parents were at work. For headline writers, riffing on the name of the system must have been irresistible. In 1985 alone, two different articles appeared with the title “Minitel, Maxi-Prix” (Minitel maxi-price).12

So what exactly went on in the messageries? What was it about these plaintext chat rooms that so compelled users and turned 3615 into such a cash cow? It varied, but many, many messageries were organized around sexual fantasies and virtual play. While few services retained logs of their chat channels, the advertisements printed in magazines, newspapers, and Minitel directories during the late 1980s offer a snapshot of how the messageries appealed to potential users.

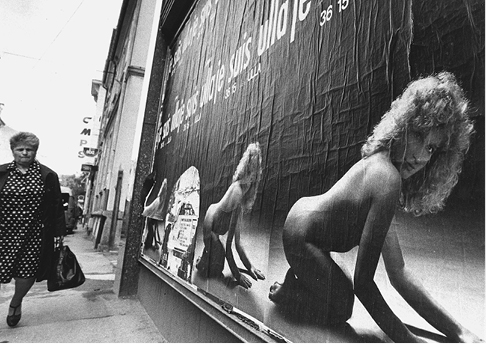

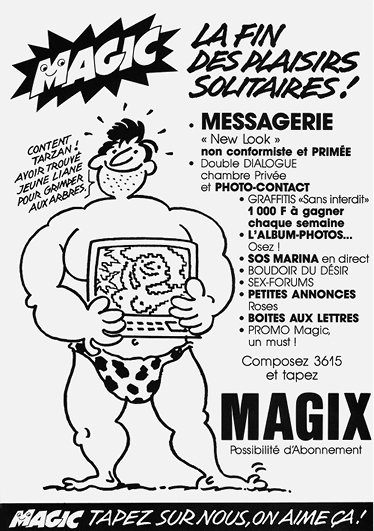

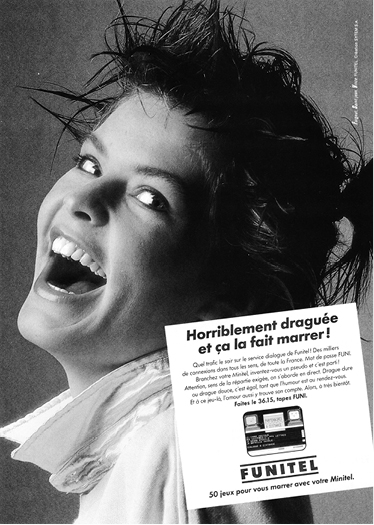

The advertising for pink messageries varied widely, reflecting a diverse array of personality, theme, and promise. Some services overtly advertised hard-core discussions with erotic imagery and unambiguous references to sexual activities (see figure 5.2). Others preferred humor and innuendo to advertise explicit services. Some focused on fringe fetishes: 3615 ANDI, for example, self-identified as “a convivial space for handicapped people and their friends,” while La voix du parano (the voice of the paranoid) was promoted as a “non-conformist messagerie.”13 Some appealed to misogynistic patriarchal values while others promised female empowerment through sexual liberation (see figures 5.3 and 5.4).14 In some cases, the names of the messageries themselves referred to sex acts, even if the advertising did not. Libération, a major newspaper, named its messagerie 3615 TURLU, in reference to the word turlute, French slang comparable to “blow job.”15 3615 SM exploited the ambiguity of its short mnemonic, branding itself as a serveur médical, a database for doctors that happened to have messageries attached—but even its streamlined, minimalist ads left little doubt as to the real nature of the service.

Figure 5.2 This ad for the Magix messagerie is rife with puns and innuendo. The subscript (tapez sur nous, on aime ça!) translates literally as “hit us, we like it!”—a play on the double meaning of the verb taper for “hitting” and “typing on a keyboard.” Minitel Magazine, no. 19, January–February 1987, 83.

Figure 5.3 This ad for the SeXtel messagerie situates the Minitel rose in a longer tradition of patriarchal heterosexuality. The illustration invites a historical comparison between Minitel and earlier uses of new media for sexual exploration such as boudoir photography. Revue du Minitel, no. 8, November–December 1986, 47.

Figure 5.4 FUNITEL portrays the Minitel rose as a more egalitarian space for sexual play, inviting women with an implicit promise of pleasure and empowerment: “She gets hit on a ton, and she finds it hilarious.” Revue du Minitel, no. 8, November–December 1986, 39.

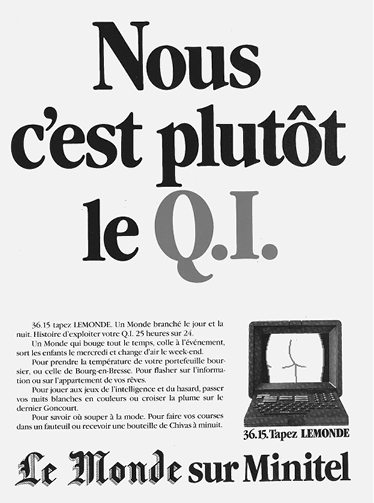

Not all messageries made appeals, either explicitly or implicitly, to sexual play in their advertising. Some systems, such as FUNITEL, did not even always mention sex, but Landaret was not alone in his belief that “all messageries were pink.”16 Without regard for context, it seemed that the use of the messageries for sex was inevitable. Even the very serious Le Monde, made purposeful, humorous reference to the use of its messageries for sex. An ad began, “We’re mostly IQ,” and then proceeded to list all the things you could do on 3615 Le Monde: challenge your IQ with games, keep up with the news, find weekend activities for the kids, manage your stock portfolio, search for your dream apartment, and order groceries from home. All this wholesome activity was punctuated, however, by a small drawing of a Minitel terminal appearing at the bottom right-hand corner of the ad. The Minitel screen depicted a pair of pixelated buttocks printed in the same pink color as the letters IQ in the title. For French readers, the connection was clear: phonetically, Q sounds like the word cul (butt). The prevalence of casual innuendo in advertisements ranging from niche hard-core services to the national intellectual newspaper of record reflected the diffusion and acceptance of Minitel rose across popular culture.

Figure 5.5 The rose phenomenon was not limited to explicitly sexual services. At first blush, this advertisement from Le Monde, a major mainstream newspaper, offers to engage your brain (“We’re mostly IQ”), but the illustration depicts another part of the body altogether. Further, the letter Q, when spoken aloud, sounds like the word cul, meaning “butt.” Source: Authors’ collection.

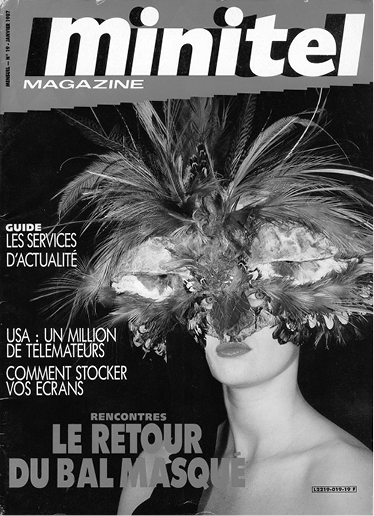

Not all chat was crude or even aimed at sexual satisfaction, however. One recurrent pattern of use highlighted in magazines and newspapers was the online masquerade (see figure 5.6). As Rheingold reported in his early work on virtual communities, many in the Minitel industry believed that their users were attracted to the liberating feeling of fantasy play:

Figure 5.6 The playful, pseudonymous discourse of the messageries was often compared to the traditional masquerade ball. Minitel Magazine, no. 19, January–February 1987, cover.

It was a chance to step out of their normal identity and be superman or a beautiful woman and say all the things that they only think about in their most secret fantasies. You are a nobody at work. You have to fight a commute to work and back. You are lonely, or you are married. Indulging in an hour of sex chat is a crude but effective way of creating a different self.17

The belief that the online masquerade offered a momentary escape from the drudgery of everyday life was widely held among minitelistes. In 1987, Marie Marchand described Cécile Avergnat, founder of the popular Crac messagerie, as having “a conviction that today’s world generates seas of solitude.” To Avergnat, then, videotex services like Crac represented a countervailing force, a means of bringing strangers back into communication. In Marchand’s words, the messagerie could be “an effective means of limiting the damage” wrought by social isolation.18

Avergnat was not alone in her view of the messagerie as a bulwark against the atomization of French society. Hannaby of 3516 SM also emphasized the value of the messagerie to people “bored with their lives.” When asked to confirm that messageries were used mostly for sex-oriented chat, his response was emphatic: “It was not porn. It was not porn.” In Hannaby’s experience, the messageries offered a dynamic social experience that ran the gamut of adult sociality. To reduce them to “porn” was to overlook the grander social experience unfolding on systems like 3615 SM. Indeed, Hannaby saw the messagerie as a space of identity play and experimentation, set apart from the everyday world:

People were able to pour all their fantasies on the system, just saying whatever they were not able to say in their real life … [Some had] five different or maybe ten different personas on the system and [were] maybe sometimes chatting on two Minitels having two different nicknames. … [W]e were able to see that these people were trying to experiment many ways of chatting, so a lot of people were simply genuine but a lot of them were taking a mask and trying to, I don’t know, seduce or chat or just have fun on the system. … It was an equivalent of Facebook today, a way for people to connect together … they were able to chat about their problems at work, anything; what happened last night with friends during a date and it was a bit of sexy talks but not only that. It was a lot of friendly talks. Being able to find a friend; someone you can talk with, you can spend time just talking about your fantasies.19

Referring to the phenomenon as “social innovation,” communication scholar Josiane Jouët also stresses the new opportunities to break free from classic social relations and meet new people from extremely diverse social backgrounds—not an easy feat in off-line life. Oftentimes, she notes, the minitelistes she interviewed “insisted that even if it did not end up in a hook up, it was always interesting to have a drink with people we didn’t know, very different people whom we would never have met through the day-to-day routine.”20 Despite their pink reputations, then, the messageries provided a context for meaningful communities to develop. In some cases, dedicated users organized off-line parties similar to the face-to-face get-togethers hosted by Echo, the WELL, and other US-based systems with less sexually explicit reputations.21 In Hannaby’s recollection, long-time users maintained the system’s social norms by helping to acculturate new users:

There was the core, a very strong core of users that knew each other and there was all these people added by the ads we had at one point, in the subway, in the magazines and so on. I think the core of users were happy to see all these new people coming in. I think that this core taught the way of using and interacting with the system. So it created a strong bond between the users, because they were using the same way of interacting that was taught by the first users. So of course, it was chatting, dating of course. People used that to date and myself, I used it to date. At one point, I had a girlfriend that I found with the system. So there were a few people that were able to marry using the system. Because of the popularity of the system, we started to organize parties. These parties gathered maybe a few hundred people at one point, so that was not too bad. I remember one of the parties was organized at the Moulin Rouge in Paris. We rented the whole space at the Moulin Rouge, so people came and had their dinner and danced, and it was fun.22

To see the messageries as a masquerade (rather than, say, a bathhouse) reveals the social complexity of these text-only spaces. While some pink systems were little more than engines for sexual release, many messageries offered a novel social space for strangers to meet—part nightclub, part salon. Just as scholars would later observe on Internet services like Usenet and Internet Relay Chat, the groups of people drawn to messageries formed bonds and relationships that gave rise to lasting communities, and perhaps to the surprise of system administrators, many were eager to extend these online interactions into their off-line lives.23

A key role in the commercial success of the masquerades as well as the cruder version of the messageries was played by les animatrices, employees of the service provider.24 Their job was to pass for actual users and tease the real users into chatting with them for as long as possible. In the words of one, since the business was the “economics of attention,” animatrices were, literally, “attention whores.”25 The animatrices were often young men—mostly college students—who passed as women, at least on the straight sites.26 They would juggle multiple connections/personas at once, either by using multiple terminals or through PCs enabling them to manage multiple virtual Minitels on one screen. They also served as compliance officers for the site; they were present 24/7, monitored all conversations, and would disconnect users breaking the law (such as prostitutes soliciting on the sites or blatant pedophiles). Some of them seemed to enjoy the work quite a bit. Hannaby remembers recruiting some of his animatrices from his user base: “They did it because they liked it.” In fact, two of his particularly enthusiastic animatrices wound up getting married. Working in the same room, surrounded by Minitel terminals, the husband-and-wife team would even chat to each other over the Minitel.27

But not all was rosy in the Minitel rose factory. Jean-Marc Manach, a college student at the time, recalls feeling like a “whore” who was not selling his body but rather his words. While some messageries encouraged friendship and community, Manach worked for a more frankly utilitarian service:

My boss, who was gay and had as much female psychology skills as a dry oyster, would yell at us when we started chatting one-on-one with the users. He wanted us to just dump lewd scripts on them, to perform strip tease, to offer blow jobs and facial ejaculations, while yelling “Oh yeeeessss! More! I’m cooommiiiiiing!” As a result, these guys would jerk off, and in a few minutes it was over. It was a slaughterhouse. I did not like it.28

The assembly-line sexuality of such messageries led some of the workers to a sense of disillusionment. As another animatrice concluded: “At the end of the day, those encounters were pretty sad, because they reflected our times: everything is communicated, but there is not physical touch.”29

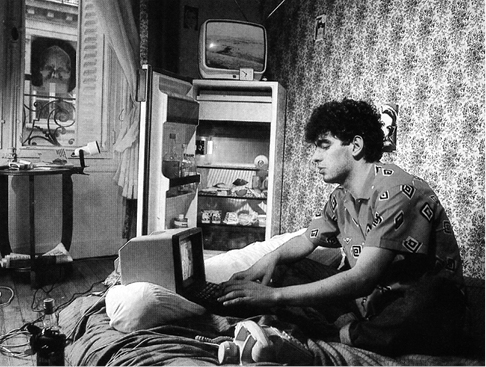

Figure 5.7 A trade magazine’s reenactment of an animatrice at work depicts “Koka,” a male college student presiding over a messagerie from his bedroom. Notice the empty fridge and bottle of whiskey in the foreground. “Koka, the Telematics ‘Disc-Jockey,’” Revue du Minitel, no. 8, November–December 1986, 47.

It would be easy for the US reader unfamiliar with 1980s’ France to understate the pervasiveness and social significance of Minitel rose in the French cité. Minitel rose was everywhere. With messageries accounting for up 50 percent of all traffic, revenue was enormous.30 And with the top twenty sites garnering 85 percent of pink connections, visibility was key.31 The result was a feedback loop that incentivized the messageries to put out more and more ads, in more and more public places. By the late 1980s, ads for Minitel rose were pervasive on the streets of Paris. Short codes such as 3615 SEXTEL appeared on any surface that could carry an ad—billboards, buses, subway stations, magazines, and television. Everywhere. Most ads were playful rather than crude; they were, after all, displayed in public for eyes of all ages. But while their level of explicitness varied, there was no question what was being advertised.32 The PTT minister would even comment that the public displays versus the services themselves were “the most shocking element of this affair.”33

It is worth noting that the press industry, past its initial reluctance, embraced the Minitel golden goose, and not just as a platform to publish news. In fact, it had an edge in this business since the legal framework put in place to regulate Minitel gave the incumbent press industry a monopoly over access to the Kiosk billing system.34 For example, popular newsprint magazine Le Nouvel Observateur notoriously became the promoter of many a pink service such as the highly successful 3615 ALINE under the leadership of legendary entrepreneur Henri de Maublanc. Le Nouvel Observateur and Le Parisien Libéré, two large press corporations, were in constant competition for the number one rank of 3615 promoters, all services combined.35 Landaret, who himself ran Gretel on behalf of a regional newspaper, went as far as stating that certain publications such as Le Nouvel Observateur, Libération, and Le Parisien only survived thanks to the 3615: “It was considered a cash machine.”36 And as far as the sites themselves were concerned, the messageries systematically topped all other services in the various rankings produced by industry publications.37 As we have noted in the introduction, the accuracy of these data is tainted, in this case because they were self-reported by the promoters themselves, but the rankings nonetheless offer a view of how the industry understood and represented itself. Regardless of which particular service was in the top slot, the messageries were the dominant form of activity on Minitel, providing a huge stream of revenue to both their owners and the State. A far cry, perhaps, from the electronic telephone book, Minitel blossomed culturally and commercially thanks to the widespread adoption of adult-oriented chat.

Pornography is an undisputed driver of new media technologies. VHS took movies inside the home, and provided countless people with the privacy a visitor to an actual porno cinema wished they’d had. Minitel, unlike the Internet, was private by design, and the privacy features of Minitel took sex chat into the workplace. Minitel flows were anonymized both on the upstream and downstream. On the host side of the platform, service providers did not see from what number users were calling. This precluded later Internet innovations such as user tracking and micro-targeted advertising, as well as prevented service operators from getting an accurate head count of their client base.38 On the user side of the platform, connections were anonymized as well: the phone bill would only list connection minutes in bulk, without detailing either the specific times of connection or destination addresses. The privacy features were key in helping the DGT move forward despite popular opprobrium in the early days of Minitel; remember that the regional press has cried Big Brother in its campaign to kill the high modernist project. Full privacy was therefore a crucial public relations tool for the DGT.

Privacy features on the user side of the platform enabled the messageries roses to enter both the home and the office. They did not prevent curious children from being disciplined for running up a large Télétel bill without permission. However, because the bill did not detail the services that had been accessed, spouses could discreetly explore the messageries under the guise of ordering food or browsing train schedules while their better half was away.39 Similarly, the aggregate billing system enabled workers to sneak in a bit of relaxing chat into the workplace. Minitels were widely used by small, midsize, and large businesses alike to manage inventories, order supplies, fulfill orders, check rates or corporate records, book trips, and so on. In fact, professional apps such as Agricom, used by swine traders, remained active until the end of 2012, when the closing of the network left many in distress.40 With all digital destinations anonymized on the bill by the DGT, it was easy for Minitel-enabled workers to escape the gloom of the workday for a few minutes here and there, and ramble into rosy paradises. Visually, the text-mode interfaces of these digital frolics also made it difficult for a zealous boss to discern the specific nature of the computing act from a distance. Just in case a compliance officer happened to pop in, some sites built in a feature that enabled the user to display a fake, “clean,” home page at the touch of a button.41 And as an added forbidden pleasure, self-employed business owners could even write off the not-so-rosy phone bill as a business expense.

Minitel rose at work was a real issue for French bosses, not for moral reasons, but financial ones. One study suggested that 15 percent of work connection time was spent on the messageries.42 Systems emerged that enabled corporate “Minitelmasters” to block access to 3615 services—but by the same token, blocking access to messageries also blocked access to useful professional sites.43 Bosses faced a somewhat-unsolvable conundrum. The press reported many stories about extravagant bills being run up at night by janitors and other blue-collar staff, also known as the “syndrome of the Minitelist night-watchman.”44

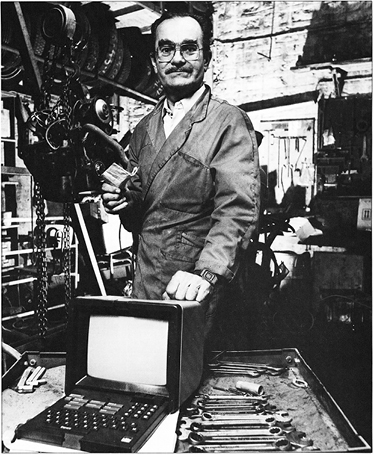

Figure 5.8 Minitel was a fixture of many workplaces, from the office to the shop floor. This photo appeared in a feature on the use of telematics by the auto industry: “[Along] with the 12″ wrench and the hub puller, Minitel has become a vital tool for the car mechanic.” Revue du Minitel, no. 7, September–October 1986, 26.

During the daytime, workers took Minitel breaks instead of hanging out by the watercooler. One office worker, known as “Wild Stallion,” was said to have written to his online counterpart, “If you called to administer a survey, please speak to my secretary. She has felt lonely since I’ve become a minitelist and started neglecting her.”45 As usual, France Telecom tried to minimize the impact of pink Minitel on the workplace. Maury, the Minitel project lead, declared that what was reported in the press were individual cases amplified by the media—“we surveyed 200 companies, not one brought up 3615 as a problem.”46 Meanwhile, the DGT as well as other ministries such as the Foreign Affairs Ministry blocked 3615 access for their workers.47 Landaret recalled being grateful to Telic employees for the time they spent on the Gretel messageries.48 And Hannaby noted, “You know, people were paying a lot but I think a lot of money came from the companies that were having Minitels and maybe France Telecom had a lot of Minitel and people in France Telecom [were] using them [laughs].”49

Beyond simply blocking access to whole categories of sites, more sophisticated access control systems emerged around 1987. Unlike filtering software à la Net Nanny that came to existence in the mid-1990s to filter the downstream flow of Internet traffic, Minitel filtering systems offered upstream control mechanisms. Maya, a board connected to the Minitel through the peripheral DIN output, could limit upstream connections to a select forty sites as well as offer time limit controls.50 Despite France Telecom’s denial that the pink workplace was even a thing, four thousand Mayas were said to have been ordered in the first month. In an editorial comment on the popularity of the new control mechanism, Minitel Magazine remarked on the conflicting interests of workers, managers, and the DGT: “Minitel at work? A great deal for the 3615. Dynamic white-collar workers are keen on exchanging tender words the second their boss turns around. A boss sometimes has an urge to put the terminal under lock and key.”51

Filtering systems aside, one man almost killed the golden goose. Ironically, it was the man who had engineered the platform in the first place. Maury, a typical engineer preoccupied by technical performance more than by policy, law, or social impact, devised a unique digital identifier similar to a web browser “cookie.” Using an eight octet sequence stored in the terminal’s memory, a disconnected user could log back onto a server and pick up where they left off.52 To speed up the reconnection, the last visited page would reload the next time that the terminal was switched on. Unfortunately, this clever function left unsophisticated users vulnerable to being tracked by anyone with access to their terminal equipment, be it a spouse or boss.

News that Minitel might gain a memory prompted social outrage. Que Choisir, a leading consumer report magazine, reacted with an article titled “Un mouchard chez vous” (a snitch in your house). The piece opened with the provocative line “Big Brother has arrived.”53 A second leading consumer reports magazine, 50 Milllions de Consommateurs, similarly expressed discontentment, and in 1985, angry users physically returned three thousand units to the PTT’s storefront.54 France Telecom immediately killed the cookie feature, saving the pink goose that it denied existed in the first place.55

To the US reader unfamiliar with French customs, the prevalence of the messageries both on- and off-line might sound baffling. In a country where comedian George Carlin was once arrested for disorderly conduct for uttering the words shit, piss, fuck, cunt, cocksucker, motherfucker, and tits as part of a political comedy routine, where radio station Pacifica was reprimanded by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) for broadcasting the same routine in violation of indecency regulations, and where the brief sight of Janet Jackson’s nipple caused over half a million complaints to be filed with the FCC, advertisements for pink services would not have seen the light of day.56 They would have been confined to specialty magazines hidden high up behind the register, veiled in dark plastic covers—not a rosy pixel in sight.

But no such moral panic occurred in France. Certainly, the Minitel rose was the source of some controversy, and crimes involving Minitel were sensationalized in the news. In one case, a user reportedly “borrowed” the moniker of someone who had gone on vacation and used it to harass other participants of the messagerie. On their return, the original moniker user became ostracized from the community and ended up committing suicide.57 In another case, a newspaper reported that a woman was raped “after meeting her torturer on the grey screen.”58 As with so much of Minitel culture, these stories of tragedy by Minitel prefigured the moral panic about meeting strangers online that gripped the United States in the late 1990s.

Just as Time chose to highlight “cyberporn” as a key threat to US children in 1995, the sexually explicit messageries were a focal point of Minitel controversies in France.59 Attempts to shut down pink services were justified under the guise of protecting minors and “other weak members of society.”60 Rather than mainstream, heterosexual pink chat, however, regulatory scrutiny fell mainly on sex workers, queer users, and the services they frequented. For example, it was well known that prostitutes used the messageries to solicit clients, and several services were shut down on that basis.61 Critics also targeted France Telecom because it cashed one-third of all Minitel revenue in its role as network operator—something both the media and General Auditor (a quasi-judicial agency that audits the executive, legislative, and administrative branches) found problematic.62 Associations of Catholic families became active in initiating complaints and lawsuits against what became dubbed “the pimp State,” and other critics would raise the alarm about “the moral decadence of the State and of the high administration.”63 The criminal code was even amended in order to increase penalties for the crimes of “offense to good morals” (outrage aux bonnes moeurs), “incitement to debauchery” (incitation à la débauche), and the publication of messages that “adversely affect human dignity” (porter atteinte à la dignité humaine) when the target of the messages are under fifteen years old—the legal age of consent in France.64

Messageries appealing to gay users came under the strongest attack during this period of moral outrage. In 1986, a mainstream daily newspaper published an exposé about solicitation and teen prostitution on Minitel. The opening paragraph called special attention to gay services: “Minitel is used as a modern pimp and meeting point to all amateurs of teenagers under 15. Since Minitel exists in a legal vacuum, the ‘gay’ servers are having a field day.” The article printed the full text of several personal ads, all of which were reportedly found on a gay service: an adult seeking “little boys,” a thirty-five-year-old offering free rent for sex, and a fifteen-year-old “awaiting financial offer.”65 In the same vein, the ultraconservative and ironfisted Charles Pasqua, minister of the interior, singled out a gay pink chat room called Gay Pied that ironically had been financed by the State’s sovereign fund, the Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations.66 While preventing the sexual exploitation of children was a reasonable goal, it seems clear that gay systems were unfairly targeted and grossly misrepresented. As a result of the conservative pressure, gay messageries were more actively monitored than their straight counterparts—by their own editors and the hosting services that hosted them.67

In spite of these alarmist reports, it is important not to overblow the significance of such outrage. As Marie Marchand, a France Telecom researcher, noted,

There is no point in exaggerating! Since the dawn of time communication has been used as a vehicle for sex. This should come as no great revelation; it is common knowledge that the phone has long served the same purpose (Paris’ renowned tarts of the turn of the century, denizens of the Bois de Boulogne, were among the first to subscribe to the telephone!), but that the telephone is put to such use is a fact of life and does not upset many.68

In fact, despite the stir, by and large the messageries remained the most popular of all Minitel services. The loudest critics often were not the most representative of public opinion.

The general public’s attitude toward the playful chat rooms was mostly benevolent; a 1991 poll found that 89 percent of the population was against Pink Minitel prohibition.69 And while a few politicians such as Pasqua (who would incidentally later twice be convicted of corruption) were vocally opposed to the pink services, this was far from the case for all of them. PTT minister Gérard Longuet, who thought that the content of the messageries was much less shocking than the billboards themselves, declared that he simply did “not want telematics to have its image tarnished by the exclusive use of fornicative fellowship.”70 In retrospect, this was wishful thinking. As competition among the pink services increased, so did the overall visibility of pink advertising in public. Ultimately, that same PTT minister would concede, “We are not going to ban hotels because there is prostitution, or public bathrooms because there is graffiti.”71 Also quite telling is a June 1987 interview with Philippe Séguin, a prominent right-wing politician who would later become the head of the General Auditor, at the time minister of social affairs, in the racy men’s magazine Lui. The discussion with the interviewer, famed television anchor Yves Mourousi, goes as follows:

Yves Mourousi:

—There are newspaper kiosks in [your town of] Epinal … [where the minister was also the mayor]

Philippe Séguin:

—Of course!

—And on them, there are billboards of young girls who give their phone number or Minitel access code?

—As is the case everywhere

—Today, when you drive around Epinal or Paris, is this a spectacle that bothers you?

—Not at all

—Do you know how to use a Minitel?

—Yes, in fact we uploaded 3,000 e-government pages in Epinal

—With a messagerie?

—With a messagerie indeed.

—Did anyone explain to you that it is the messagerie that makes money?

—With a messagerie, we take full advantage of interactivity. Our relationship with citizens goes through Minitel. They can send us their grievances—a broken sidewalk, or anything else. And our rule is to answer them within 48 hours.

—When certain members of your government say that we must control Minitel, because it can be used for sexual outburst or nocturnal fantasies. … In Epinal, do you have such controls in place?

—If we go down this route, we’ll have to ban the telephone too?

—Are the messageries something that revolts you?

—Not one second. And if it helps popularize Minitel, then why not? Minitel is a fantastic invention.72

That the minister of social affairs himself would take such a position is telling of the overall benevolence—even affection perhaps—with which French society as a whole approached the rosy side of Minitel.

Finally, a rather-bizarre editorial sums up the French attitude toward the messageries quite well. In the summer of 1986, Minitel Magazine, under the heading “DECENCY,” declared that it would from now on refuse to publish any advertisement that “directly and crudely called upon sexuality.”73 At stake, explained the editor in chief, was the reputation of telematics: “There are people who understood quite quickly that one of the juiciest market[s] was sex. … [A]nd porn, trust me, is very strong. So of course since they make money, they advertise … maybe a little too much. We’re not going to censor, that’s not the issue, we’re just saying that telematics is not just [sex].”74 While sexually explicit services sparked early interest in Minitel, videotex advocates like the editor of Minitel Magazine were concerned that the stigma of porn would stymie the potential for telematics to grow beyond the messageries. “French telematics is recognized everywhere as a great success,” continued the editor. “It must therefore not become tainted in bright pink if it wants to continue in the direction of success and not become a specialized network. A few services must not jeopardize the image and the formidable potential of Minitel. This deserves some prudishness.”75

Both the editor of Minitel Magazine and the aforementioned PTT minister were concerned that Minitel was becoming known exclusively for its pink services. They were not worried about the content of the messageries but rather the outside world’s perception—a serious issue given that France was busy trying to export Minitel.76 In spite of the editor’s call for “decency” and “prudishness,” Minitel Magazine did not cease running sexually explicit advertisements. In fact, the very same issue that called for a ban was itself riddled with ads for pink services.77 Telematics enthusiasts may have been concerned by the overwhelming attention paid to the messageries roses, but they certainly were not willing to give them up.

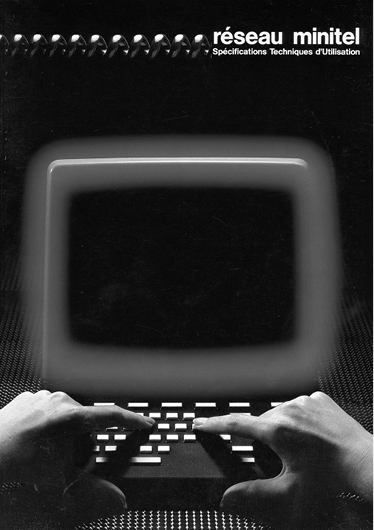

New media technologies are often sites of moral conflict, and telematics was no exception. In the mid-1980s, a loud conservative fringe in France reacted with moral outrage to the pink services on Minitel, but there was no widespread moral panic like the one that would form a decade later in the United States. Instead, French society seemed generally bemused by the unexpectedly risqué turn taken by their telematics system, and the flow of pink revenue was certainly welcome by Télétel administrators. Was it any coincidence that France Telecom printed a user manual with a glowing pink terminal on the cover?

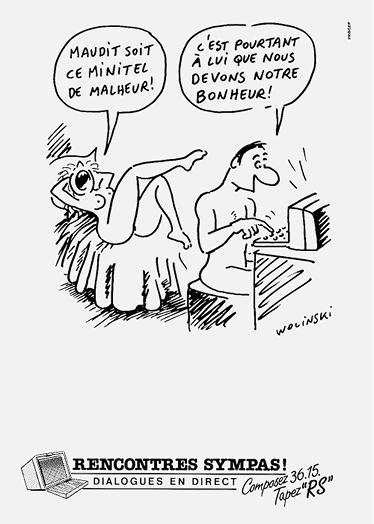

Figure 5.9 This ad for 3615 RS—Rencontres Sympas! (friendly meetings)—features a satirical cartoon by Georges Wolinski. A nude woman lying on a bed cries out, “Damned be this Minitel of doom!” to which a man seated nearby answers, “But it is to it that we owe our happiness!” Ironically, the ad appeared in the same issue of Minitel Magazine as an editorial proclaiming the magazine would no longer publish advertising that “directly and crudely called upon sexuality.” Minitel Magazine, no. 16, August–September 1986, 26.

Figure 5.10 A glowing pink Minitel on the cover of a technical documentation suggests a winking recognition of the popularity of the messageries. Direction générale des télécommunications, Réseau Minitel: Spécifications techniques d’utilisation (Paris: Ministère des Postes et des Télécommunications, n.d.). Source: Orange/DGCI.

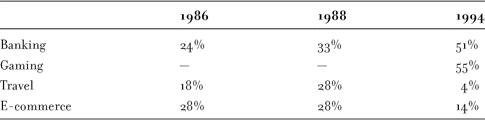

The range of Minitel services was huge.78 With over twenty-five thousand sites at its peak, Minitel provided a depth and breadth of data and services, from general to niche, that only the World Wide Web would rival. Rather than making a list, we have selected a few innovations that prefigured what the post-1995 Internet would offer. Data published by France Telecom indicated that the top services, by category, remained fairly constant over the years: banking, gaming, transportation, e-commerce, general information, and “the press” (which includes both traditional media sites and the messageries they hosted).

Table 5.1 Proportion of Users Accessing Various Types of Services during the Previous Year

Source: Orange/DGCI.

Data published by France Telecom offer a sense of market dynamics, but must be taken with a grain of salt. First, France Telecom did not use the same service classifications every year, which makes accurate comparison over time impossible. Second, it seems clear that the books were cooked when it came to reporting Minitel rose. For example, in 1987, France Telecom reported that the messageries accounted for 16 percent of traffic. But in 1988, after Minitel rose became somewhat scandalous, it retrospectively reported that the messageries were only visited by 5 percent of users in 1986 and 9 percent in 1988 while also introducing “the press” as a distinct category (with 25 and 16 percent participation, respectively). Splitting the messageries and press into separate groups was an obvious attempt to minimize the impact of the messageries since the chat rooms were the primary reason that many users visited the press sites. The press category therefore should have been taken into account as a noisy measure of Minitel rose activity. In subsequent publications by France Telecom, messageries would sometimes appear (in 1992, 6 percent of users reported accessing messageries de charme), and sometimes not (in 1997, only “the press” was a category, with 7.1 percent of users visiting). And when messageries were reported, the data were inconsistent. France Telecom, for instance, reported that only 1 percent of users visited the messageries in 1994, but in July 1999, in a special issue discussing why Minitel was better than the Internet and should be kept by users as their primary online venue, it reported that 21 percent of users were still using the messageries. Rather than paying too much attention to these rankings, then, we now describe a few services that prefigured what the web would later offer.

The history of Minitel offers early glimpses of many of the social and political issues that surround the Internet today. Examining how these issues played out in the context of Minitel supplies a new perspective for thinking about current-day design and policy challenges. Similarly, Minitel provided an early platform for minitelistes to experiment with business ideas that would later become staples of the Internet … for good or bad. Some of the early practices we document in this section are trivial but worth mentioning for their entertainment value; some provide provocations for thinking about policy conflicts and business models in new and future online ecosystems. Before there was …

In 2008, Webvan was dubbed “one of the most epic fails in the dotcom bubble fiasco … a cautionary example of how not to start your Web business.”79 This online grocery store, the business model of which still remains unclear, “went from being a $1.2bn company with 4,500 employees to being liquidated in under two years.” Before there was Webvan, however, there was Tele-Market.

Figure 5.11 Françoise Marceau, Tele-Market’s head of client service, poses with her Minitel in front of her “Minitel-Van.” Tele-Market Minitel-Van,” Revue du Minitel, no. 2, September–October 1985, 18.

Tele-Market promised to deliver food to the Paris area and offered same-day delivery. It competed with several other companies; a 1987 guide lists four different services focused on delivering to the Paris area, and twenty-three total in France, enabling one to order from large stores, specialized wine retailers, or straight from local farms.80 The story does not tell whether any of these businesses were successful (we know that they never made the top list of the industry magazines). But at least, unlike Webvan, they drew revenue from the per minute fee that the user had to pay while browsing the catalog over a 1,200 baud connection, which, all things considered, did not make these ventures unreasonable gambles, considering these sites offered up to two thousand products each.81

In a country where language is highly codified and placed under the protection of the Académie française, the messageries provided a welcome playground for those who wanted to free themselves from conventions and could not handle a huge phone bill: contractions, phonetic language, and symbols were much quicker to type—a crucial advantage for users billed by the minute. While the practice of butchering language raised some eyebrows, it was mostly looked at with amusement and benevolence by the specialized press.82 Conversely, other authors noted that some users actually developed highly sophisticated styles, some even writing poetry using verses; since no pictures were available, the power of words were the ultimate tool of seduction.83

Before the University of California at Berkeley launched SETI@home, a “scientific experiment that uses Internet-connected computers in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI),” in 1999, Minitelists were able to chat with aliens, or at least send them messages, through the Cosmos Art Initiative, “the first intergalactic messagerie.”84 Messages typed on the Minitel screen were beamed into space through the Nançay radio telescope, another jewel of the post–World War II French technological renaissance. Things would turn full circle when said radio telescope joined the SETI program.85

The France Telecom telephone directory, known as Le 11, featured a natural language interface. Name searches could be successfully completed even when the name or address was spelled wrong, and the yellow pages sections of the State-run directory as well as the Minitel online directory MGS offered powerful natural-language search capabilities. For example, one could search for “reservation of theater tickets in Paris” or “residential real estate rentals in Lyon.” By May 1991, France Telecom would boast a 98 percent rate of accuracy in the search results.86

In addition to natural-language interfaces, the private sector also experimented with on-demand personal assistants and semantic search. Before Apple’s Siri or Microsoft’s Cortana, Minitel users could chat with Claire or Sophie. Claire provided administrative information, while Sophie answered questions on Parisian cultural activities. But Claire and Sophie were not powered by artificial intelligence software; there were real, live people on the other end of the connection, referred to as “Minitel girls.” That was 1984.87 Truly automated personal assistant services with natural-language interfaces began to appear around 1987, such as 3615 AK, a public-facing database of health information similar to WebMD.88

Several systems were developed to purchase tickets online. Le Point, a major French magazine, enabled one to order tickets from the comfort of one’s home by simply providing a bank account number (something not nearly as risky as over the Internet thanks to Transpac’s advanced security features). Tickets would then be delivered by mail.89 Fnac, France’s main chain retailer of cultural goods, set up public access points connected to Transpac where one could pay by credit card and have the ticket printed. It subsequently attached those points to Télétel, so one could order from home and then go print the ticket at the access point.90

In the early 2010s, many tech companies began to invest in a vision of the future dubbed the “Internet of Things,” in which “physical objects, such as sensors or everyday objects like appliances and vehicles … are capable of structured communication to and from remote databases and between themselves.”91 But this vision of home automation was hardly new. Before there was the Internet of Things, there was a Minitel of Things, or as the French call it, domotique, from the Latin domus (house) and the French informatique (informatics)—in other words, the smart house. Before the Nest thermostat became all the rage in Silicon Valley (with its obligatory billboard on the 101 South Freeway), the French were layering such systems over the Minitel platform. The Minitel terminal—and specifically, its serial port—played a central role in coordinating the domotique network. First, it provided communication to and from the outside world by supplying an interface between the various “smart” devices in the home to the telephone system. This enabled cybernetic devices to communicate with the outside world. For example, a domotique fire alarm could ring the firehouse.92 Similarly, the Minitel could receive orders sent remotely and communicate them to the control unit. Just as Télétel enabled third parties to independently experiment with new services, the Minitel-enabled vision of domotique was vendor neutral, enabling independent corporations to develop a variety of devices and applications.93 The present-day vision of the Internet of Things depends on the same openness: devices can be remotely controlled from any computer as long as they both use IP as the network protocol, and the Internet service provider does not discriminate against them. Domotique devices from the 1980s included thermostats, VCRs, security systems, lights, yard irrigation, and even kitchen appliances—although it remains unclear why anyone would want to remotely control a stove, fridge, or supply of laundry detergent or trash bags.94

Figure 5.12 Minitel provided a convenient platform for the production of numerous peripherals. The Ligne Directe system from IDT promised home automation (domotique) with remote control via Minitel. Advertisement, n.d. Source: Orange/DGCI.

A more successful use of the Minitel serial port was to create a local area network. A strong peripherals industry developed as a result of the terminal’s open standards and device neutrality. Peripherals were sold to make data more permanent (e.g., a printer or external storage device) or the terminal smarter (e.g., a computer could be attached to manipulate the data), or turning things around, the Minitel itself could become a peripheral for a computer—that is, a modem—used to download software or communicate through BBSs.95 The number of peripherals available was large, both in depth and breadth. Products included printers, analog and digital voice recorders, external hard drives, autodialers, voice-mail systems, screens, projectors, systems enabling the sending of signals through coax television cables (similar to today’s Slingbox), voice synthesizers, optical disk readers, and electronic billboards. A 1989 guide published by France Telecom listed 266 product lines from 123 independent providers—quite the counternarrative to Minitel as a closed system entirely run by the State.96 Though Télétel failed to boost the domestic computer industry, it worked wonders at stimulating a market for Minitel peripherals.

Banking has historically been a driver of innovation in information technologies, and Minitel became a natural playground. While online banking experiments in the United States such as Covidea in 1985 (launched by the Bank of America and Chemical Bank in cooperation with AT&T and Time, Inc.) and a venture supported by Citicorp in 1986 were failures, online banking became an early staple of Minitel.97 The first service, Vidéocompte (video account), was launched on December 20, 1983, by CCF Bank (now part of HSBC). But far from being what the Financial Times called an “electronic gadget,” within a year the service attracted 65 percent of CCF clients who owned a Minitel.98 Other banks were a bit less successful, for unlike the CCF, they actually charged a monthly fee for the service.99 A 1991 France Telecom survey estimated that “the penetration ratio (total subscribers/total bank customers) average[d] 8% for nationwide banks and 19% for local banks.”100 Nonetheless, that was enough for banking services to repeatedly be ranked in the top of all services by France Telecom. Services ranged from checking balances and making appointments with bank personnel, to ordering checkbooks and transferring money. Using Minitel as a modem, the home or office accountant could download banking data to further manipulate it using a personal computer.

The contrast between the successful Minitel model for online banking and US videotex failures in this realm highlight the power of Minitel as a neutral, open platform on which private actors could layer their services. In contrast, the fragmentation of US systems made it impossible for banking services to succeed. Different banking applications required separate subscriptions to distinct gated communities and sometimes dedicated hardware.101 The United States would have to wait for the privatization of the open Internet as a neutral, open platform to see the successful emergence of online banking in the retail sector.

The day trading of securities also became a reality long before the likes of E*Trade would open the US markets to retail investors. Some services enabled the management of mock portfolios as competitive games. For example, FUNITEL diversified its messagerie business, and “launched the Stock Market game in which the trading rates on the Paris Bourse were made available on-line and updated daily. Players managed a fictitious investment portfolio valued at $100,000. The winner took home a sum equal to the amount of money ‘made.’”102 And many services provided actual portfolio management and same-day online trading. As a trade magazine pointed out in 1987, Minitel was particularly well suited to a time when a wave of corporate privatizations, financial markets deregulation, and high volatility required that one be well informed and act fast.103

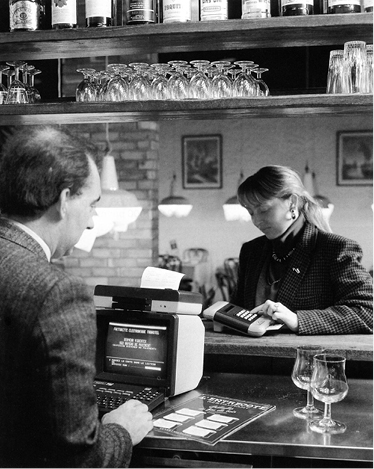

Before US merchants could accept secure payments over the Internet, a system named LECAM enabled Minitel users to both send and receive online payments. The system was based on smart chip cards—another invention developed in France and sponsored by the State as part of its digital plan.104 It enabled secured payments to be made to a merchant from home or a point-of-sale system, in real time. Initially, smart card interfaces were sold as peripherals, but, due to the popularity of Minitel-based payments, later models of the Minitel terminal included a built-in card reader (see figure 2.6).

Figure 5.13 A restaurant customer pays her bill using a secure chip card reader connected to a Minitel 1B, circa 1988. With the addition of a smart card reader, Minitel became an affordable point-of-sale system enabling businesses to accept payment cards. Direction générale des télécommunications, La Lettre de Télétel, no. 16, Q1, 1989. Source: Orange/DGCI.

A testimony to its mass-market retail success, Minitel figured prominently in French popular culture during the 1980s and 1990s. In contrast to contemporary systems in other parts of the world, Minitel use was depicted frequently in French television and film, and referred to in the lyrics of pop songs. Whereas many Americans born in the 1970s would regard a 1980s advertisement for CompuServe as a historical oddity, their French counterparts would react to a similar Minitel ad with nostalgia. The French denizen will associate Minitel with milestone life experiences: the first computer, the first online chat, university registration (which required the use of Télétel), and the first online gaming or shopping experience. And if not memories of an actual online experience, the ad will trigger the recollection of the possibility of the experience. The role of Minitel in the cultural memory of France exceeds the actual use of Minitel in the everyday lives of French people.

Billboard, television, and radio and print advertisements were omnipresent. Other, more typically French media formats also made it seem that each and every consumer good now had a 3615 companion. Lapel pins were all the rage in France in the 1980s and 1990s, and pins featuring 3615 services became part of this trend. Phone cards equipped with smart chips were pervasive in France during this same period due to the practical impossibility of making pay phone calls with coins. The disposable cards served as a prime advertising medium for Minitel services, especially since phones and online services were linked both in practice and in the popular psyche.105 This helped Minitel enter popular culture not only because phone cards were present in everyone’s wallet but also because they quickly became trading cards, both in schoolyards and adult marketplaces. Where Americans traded baseball cards and pogs, the French traded Panini soccer cards and used DGT phone cards. As phone cards became part of mainstream popular culture, so did Minitel.

In what appears to have been a positive feedback loop, traditional mainstream media such as books and records in turn appropriated Minitel, this time not as a provider of advertising revenue but rather as a narrative theme in its own right. For example, Premiers Baisers (first kisses), a popular television sitcom for teenagers focusing on the trials of young romance, extended its fictional world through a series of books, an early form of transmedia storytelling.106 One of the books centered on Minitel. Titled L’inconnu du Minitel (The stranger from Minitel), it offered a PG-13 version of the countless erotic stories that revolved around a mysterious Minitel paramour.107

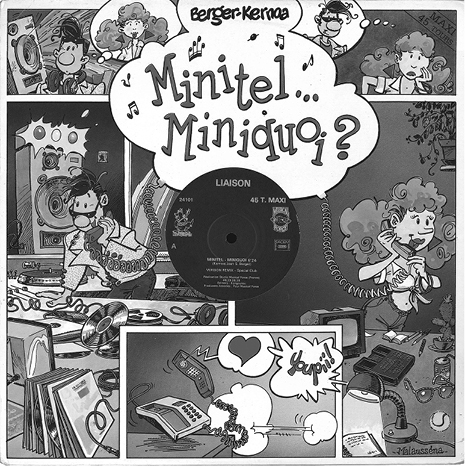

The impact of Minitel on society was also heard in the pop music of the period. Songs about online intimacies and the thrill of the digital masquerade contributed to reinforcing the platform’s position as a mainstream cultural artifact, even for those who, because of socioeconomic status, age, or choice, continued to reside solely in the analog world. Minitel … Miniquoi? by Liaison is a subtle synthpop record.108 Les Inconnus, a group of comedians that was a staple of prime-time French television at the time, parodied 1980s’ French rock: in “C’est toi que je t’aime” (It is you who I love you), the group narrates the story of a downtown boy courting an uptown girl; to woo her, he promises to be polite with her mother, vote for Jacques Chirac (then right-wing mayor of Paris and future president of the Republic), and stop surfing 3615 ULLA (the most famous of pink messageries).109 Noe Willer’s “Sur Minitel,” Marie-Paule Belle’s “Mini-Minitel,” and Les Ignobles du Bordelais’ “Minitel” each discuss the novel challenges and vicissitudes of meeting a lover online.110 Willer sings about overcoming shyness, and Belle recounts “undressing him with my digital fingers.” Les Ignobles du Bordelais narrate the story of a gentleman who meets a young lady over Minitel while his wife, Simone, is at work. After days of electronic flirting, she agrees to speak on the phone. His anticipation peaks as she picks up the phone—she must be naked!—only to discover that the voice on the other end belongs to Simone, who was herself expecting a young stud.

Figure 5.14 The illustrated sleeve for the twelve-inch maxi-single Minitel … Miniquoi? by pop group Liaison depicts a telematic love affair in full-color comic book style. Jointly released by the Kangourou and Musical Force labels in 1987 with catalog number 24.101. Source: Authors’ collection.

As a testimony to the Minitel pop cultural legacy, in 2014, two years after the termination of the ecosystem, a popular publisher printed a book titled Minitel and Fulguropoint: Le monde avant Internet.111 The title is a reference to both Minitel and the popular cartoon Grandizer, and plays on 1980s’ nostalgia. It was followed in 2015 by a self-described “nostalgeek party” at a popular Paris theater. Minitel lives on—in the collective memory of premillennial French people.

The book and party were subtitled The World before Internet; we subtitled ours Welcome to the Internet to suggest that the history of Minitel prefigured the innovation opportunities and economics, law and policy issues, the world now has to grasp. In the conclusion, we will discuss the lessons of the Minitel platform experience along with the ways they can help us devise better Internet policies for the future. But let us now turn in chapter 6 to a consideration of the radical potential of the Minitel system in the hands of a creative populace and show that the seemingly tight grip of the State over Minitel did not prevent fringe uses of the network.