CHAPTER THIRTEEN

Of Murres and Muddlers

An ingenious angler may walk by the river, and mark what flies fall on the water that day, and . . . if he hit to make his fly right, and have the luck to hit, also, where there is store of Trouts, a dark day, and a right wind, he will catch such store of them as to encourage him to grow more and more in love with the art of fly-making.

—Izaak Walton,

The Compleat Angler (1676)

“Try not to kill anything on your way home!” a friend called out as I left the dinner party, and everyone laughed. The roads were good and I had only a few miles to go, but he wasn’t entirely kidding. After all, I was driving the Truck of Death.

On the surface, it looked like a perfectly normal Toyota pickup—gray, with a white stripe and a matching canopy. I’d gotten a pretty good deal on it used, but quickly began to realize why the previous owners had been eager to sell. The engine ran fine and the body was in great shape, but that truck had a strange and disturbing habit of killing any animal that happened to stumble into its path. I often arrived at work with chickadees or juncos smashed in the grill, and once found a kinglet wedged under the arm of the windshield wiper. Then I hit a rabbit. Then two more rabbits, a cat, two crows, a robin, and an indeterminate number of voles and other small mammals. Recently, I had flattened a four-point buck in the middle of a national park.

As a biologist, I’m accustomed to collecting the occasional specimen or two for the sake of science, but before buying that Toyota, the death toll from my entire driving career had amounted to one Rufous-sided Towhee. I don’t know if it was the color, the shape, or something more sinister that made that particular pickup so deadly, but I’d begun to dread getting behind the wheel. What made it particularly creepy was that, like something out of a Stephen King novel, the Truck of Death came through every collision without so much as a broken headlamp or a scratch in the chrome.

So when my headlights picked out a small dark lump lying in the roadway ahead, I knew enough to hit the brakes. It looked like a discarded T-shirt or a bundle of rags, but as the truck rattled to a stop, front tires only a few feet away, the rag pile suddenly peered up at me and blinked.

The word incongruous comes directly from the Latin for “not fitting” or “out of place.” Finding a strictly oceangoing bird sitting placidly in the middle of a dirt road seemed to fit the definition rather nicely. Common Murres are members of the family Alcidae, the auks, a group of sturdy, plump seabirds that use their wings to “fly” underwater in pursuit of prey. They spend their lives entirely at sea, making a brief annual stop at coastal cliffs or rocky islets to breed. It appeared that my pickup truck, having run out of new terrestrial fauna to kill, had found a way to start attacking ocean creatures.

The murre looked perfectly calm and composed sitting there in the headlights’ glare, as if I were the one in the wrong habitat. But it was obviously disoriented, having mistaken the flat surface of the roadway for a calm stretch of water. The same confusion occasionally afflicts whole flocks of alcids, who’ve been known to come careening down onto wet parking lots or airport runways. Once grounded, they can only flop about awkwardly and have little hope of getting airborne again—their plump, heavy bodies require the buoyancy of water and a long running start to take flight. I pulled over and parked, hoping the murre’s landing hadn’t been too hard. They’re tough, well-padded birds, and I wasn’t worried about broken bones, but a single damaged feather could be the difference between life and death.

The murre let out a hiss and lurched away as I approached, but this was not muttonbirding, and there was no burrow to retreat to. I ran forward and grabbed it from behind, pinning its wings carefully to its body. At first it struggled, then turned its head and bit me, clamping down hard on the fleshy part of my thumb with its stout, strong bill. This had an immediate calming effect, something I’ve noticed in other birds and even some small mammals: once they get their fangs into you, they feel their job is done and it’s all right to relax and enjoy the ride. The bird held on tight as I turned it upside down to inspect the belly feathers. They looked fine. No scuffs, no broken shafts, no down poking up through the plumage; just a perfect white smoothness reflecting brightly in the headlights. This bird was ready to go back to the water.

At that point I realized that my plan had a few flaws. I was holding the murre, the murre was biting me, and the beach was a mile away. I had no way to put the bird down and nowhere to put it. I couldn’t possibly drive—I didn’t even have a free hand to turn off my headlights. That’s how I found myself walking down a country lane in pitch darkness, talking soothingly to the seabird chewing on my hand. More recently, I’ve employed similar techniques to get my infant son back to sleep, but on that night it gave me another occasion to marvel at feathers.

Had I found a single blemish in that bird’s plumage I would have had to take it home and get it to the local wildlife rehabilitation center, where it would have stayed indefinitely, living on old bait fish and cat food until its next molt. Returning a seabird to the ocean with its feathers in disarray would be a fate as certain as leaving it in front of the Truck of Death. Water draws body heat from unprotected skin at rates up to twenty-five times as fast as air. In the chilly currents off our island, an unprotected person can show signs of hypothermia in ten minutes and rarely survives as long as an hour. Birds, with their tiny body mass, would last a fraction of that time unless they were safely sealed inside their feather coats. From my stranded murre to Emperor Penguins leaping through holes in the Antarctic pack ice to the Mallard cadging bread crumbs in a city park pond, any bird living a life aquatic must be watertight. It’s an odd paradox: water birds never get wet.

For generations, ornithologists attributed this phenomenon to preen oils, the waxy secretions that birds spread liberally on their plumage during daily bouts of grooming. Watch any preening bird and you will see it repeatedly twist around to root at a spot directly above its rump, but this behavior has nothing to do with scratching an itch. The bird is simply loading up on oil from its preen gland, a specialized organ whose lipid-rich secretions help keep feathers supple. At first glance, the connection to waterproofing seems obvious: oils are notoriously water-repellent, and the largest known preen glands are found in aquatic birds, species like prions, ducks, and pelicans. Later studies suggested that specialized feathers called powderdown also played a role. Again, the logic seemed intuitive: they shed tiny keratinous flakes that had the drying properties of talcum powder, and many birds with the most prolific powderdown appeared to have reduced or absent preen glands.

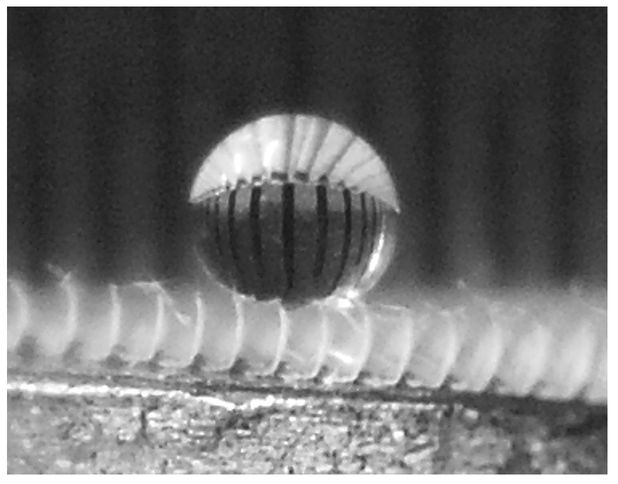

Intuitive logic needn’t be true, however, so I decided to test it. I took a flight feather from a road-kill goose out on the porch of the Raccoon Shack and poured water on it. The liquid beaded up and ran off immediately in perfect silvery droplets, leaving no trace of dampness behind. Under magnification, I watched the water stream off the rachis and form into jewel-like drops, perching on the intricate barbed lattice of the vane. The underside of the feather remained absolutely dry. But whether this was due to some lingering residue of powderdown or preen oils, or the structure of the feather itself, was no clearer. I needed to step my test up a notch and take some advice from Jan Miner.

For twenty-seven years, Miner, an American actress, starred in a famous series of television commercials, portraying a wisecracking manicurist named Madge. Each installment featured her dunking some unsuspecting woman’s fingertips into a bowl of Palmolive dish soap and then nattering on about its softening virtues before revealing, “You’re soaking in it.” Madge’s liquid detergent softened her client’s skin and nails the same way it cleaned plates, by breaking down grease and natural oils into tiny particles, allowing water to penetrate to the underlying surface. With this in mind, I took my goose feather to the house and subjected it to a good hot scrubbing in the kitchen sink.

It emerged from the suds looking utterly ruined, wet barbs clinging to the rachis or clumped together in dark mats. Once the feather dried, however, it quickly regained its familiar shape, and even my clumsy attempt at preening managed to rezip most

Seen in cross-section, this scanning electron microscope image shows a water droplet perched on the barbs of a Common Pigeon feather.

Most feather researchers now agree that structure is the key to waterproofing. Their experiments have subjected feathers to cleaning by harsh detergents or ethyl alcohol, and they have come up with pressurized contraptions to force water and air through the plumes. In spite of such treatment, flight feathers and contour feathers demonstrated their resistance to water time and time again. Only down feathers appear to be soakable, and even those offer some level of water resistance. Mallard ducklings manage to keep dry within their natal down on regular swims just a few days after hatching, before their preen glands have even started producing oil.

The lightweight, efficient, easily repaired, and extremely effective waterproofing microstructure of feathers is beginning to attract a lot of attention, and not just from ornithologists. Physicists, engineers, and inventors have an interest in water resistance, too, and top-flight research on feather structure now appears regularly in publications such as the Journal of Colloid and Interface Science and the Journal of Applied Polymer Science—very far from ornithology’s stomping grounds. Some of the titles indicate how the rewards have changed: this isn’t just about intellectual satisfaction. As the makers of Gore-Tex and other Teflon-derived fabrics have shown, waterproof materials are a multibillion-dollar business. But where Teflon production requires polluting chemicals like perfluorooctanoic acid, feathers are waterproof naturally and may hold the key to an environmentally friendly alternative.

Just how they do it remains something of a mystery. I contacted a Chinese scientist whose team had studied the microroughness of plumes from twenty-nine different bird species. They calculated the number of “touch points,” all the tiny edges and corners in the lattice of a feather vane that come into contact with water. Most birds have dozens of touch points in every square millimeter of feather surface, but that number increases dramatically for many water birds, up to an incredible nine hundred distinct points per millimeter in a Jackass Penguin feather. He told me it was the density of touch points that determined water resistance—all those distinct places pushing against the natural surface tension of the water. On the other hand, an Israeli physicist was adamant when he explained to me it was the air pockets trapped between touching points that actually repelled the water, not the points themselves. He had taken electron microscope images of a tiny water droplet perched atop a pigeon feather, with air pockets clearly visible between the feather barbs below. Increased density of barbs (and barbules and barbicels), he argued, would increase the number of air pockets and the degree of water resistance correspondingly.

The mechanics of what actually happens when water touches the surface of a feather remain very much in question, but one thing is certain. Considering their light weight, flexibility, and thinness, feathers offer one of nature’s most versatile and efficient waterproofing membranes, a feat of engineering that scientists (and the folks at Gore-Tex) would love to sort out.

In the meantime, biologists are using new insights on feather structure to sort out some long-standing questions about water birds. Cormorants and shags, for example, provide an interesting twist on the waterproofing story. A family of long-necked divers famed as trained fishing birds in Japan and China, they occur around the world and share a distinguishing trait: their outer feathers get soaked every time they plunge below the surface. From the standpoint of diving, this gives them an obvious advantage—less air trapped in their plumes means less buoyancy, making it easier to stay under and chase after the fish and crustaceans that make up their diet. (Loons, another agile diver, have unusually solid, heavy bones for the same reason.) Early observers thought cormorants must lack functional preen oil glands, surviving instead by a combination of dense underplumage and their habit of perching for long periods between dives with their wings extended, apparently air-drying their feathers. But closer examination revealed typical preening habits and glands of normal size and function; once again the real answer lay in feather structure.

A cormorant contour feather is loose and wettable only around the periphery of the vane. Toward the rachis, the barbs become increasingly dense, with nearly as many touching points as a penguin feather. A waterproof layer is maintained by tight overlapping of the plumage, with no gaps between those densely barbed interior vanes. In this context, the shags and cormorants come off looking rather smart. Rather than unkempt survivors with wet feathers and a crummy preen gland, ornithologists now view them as beautifully adapted to a diving lifestyle. They benefit from the negative buoyancy of soaking, while still keeping their skin and down feathers sealed inside a watertight blanket.

While the need for waterproofing is obvious for diving cormorants or a stranded Common Murre returning to its cold sea, every bird species lives exposed to the weather and needs a way to avoid getting drenched. I once watched a Rufous Hummingbird huddled over her nestlings during an unseasonably cold downpour. I felt damp and chilled in a parka and a wool sweater—it seemed impossible that such a tiny bird or her chicks could survive. But of course the water simply sluiced off the feathers on her back and wings, keeping everything dry below. Later that spring, all the youngsters fledged.

For birds, the outermost layer of plumage is a vital barrier to the elements no matter where they live. Water resistance was once even proposed as a driving force behind the evolution of feathers. That now seems unlikely, since no one believes that the first quills and down predicted by Prum’s theory were waterproof. But with their intricate touch points and air pockets, vaned feathers seem surely to have been fine-tuned by this function, adapted not only for flight and display but to keep birds warm and dry in any weather.

The only noteworthy exception to the watertight rule occurs in some of the driest places on earth, where desert sandgrouse live with a whole different set of worries about water. When British naturalist Edmund Meade-Waldo first described sandgrouse breeding behavior in 1896, no one believed him. Found in arid regions from the Kalahari north to Spain and as far east as Mongolia, the various species of sandgrouse all nest on the ground, in simple scrapes or even in camel prints, often as far as thirty miles from the nearest water source. They eke out a living eating dry desert seeds and must drink regularly to survive, so adults fly round-trip to water several times every day. Meade-Waldo reported that during the breeding season, male sandgrouse would linger at the pools, wading in and methodically soaking their chests before returning to the nest. Upon his arrival, the thirsty chicks rushed out to eagerly drink at Papa’s breast, sucking water straight from his feathers.

Though Meade-Waldo wrote several papers on sandgrouse and went so far as to raise the birds himself and observe this behavior in captivity, the scientific community dismissed his story as fantasy. Not only did it sound ludicrous, but it flew in the face of well-established scientific wisdom. Everyone knew that feathers repelled water; they didn’t absorb it. And even if the plumes got soaked, how could they possibly remain so when flying at high speeds for thirty miles through hot desert air? It would take sixty years, repeated field observations, and an electron microscope to prove Meade-Waldo right.

Again, the answer lay in structure, a peculiar sandgrouse quirk that makes the barbules of male breast feathers (and to a lesser degree on females) grow not in a tight lattice but in loose, springlike coils. Under magnification they look something like plastic pot scrubbers, and each tiny spiral can soak up a surprising amount of liquid. Ounce for ounce, sandgrouse feathers hold two to four times as much water as the average dish sponge. Even after a long flight through the desert, a male sandgrouse in good plumage can provide each of his offspring with several beakfuls of cool, refreshing water.

I would have welcomed a blast of warm desert air by the time my murre and I reached the beach, but the breeze coming off the water had the damp, chill bite of a Pacific Northwest winter. Plunging into the wind and waves was just what the bird needed, but part of me still felt like taking the poor thing home to warm up beside the woodstove. The night was pitch-black, cloudy with no moon, and I felt my way slowly over the driftwood before finally reaching a clear sweep of gravel and sand. When I knelt to set the bird free, we released our grips on one another at the exact same instant, as if this were a dance we had rehearsed many times. In the darkness, I rubbed my thumb and listened as he scrabbled down to the safety and comfort of a frigid sea and was gone.

While the structural physics of touch points and surface tension remain debatable, the metaphysics of feathers and water are well known. Contemplative thought goes hand in hand with plumes and flowing water, embodied in a cultural tradition that may stretch back to the first person who ever pondered trout in a stream. Fly-fishing as sport and compulsion dates at least to the second century AD, when Greek historian Ælian famously described the angling habits of locals on a Macedonian river: “They fasten red (crimson red) wool around a hook, and fix onto the wool two feathers which grow under a cock’s wattles, and which in colour are like wax. Their rod is six feet long, and their line is the same length. Then they throw their snare, and the fish, attracted and maddened by the colour, comes straight at it, thinking from the pretty sight to gain a dainty mouthful; when, however, it opens its jaws, it is caught by the hook, and enjoys a bitter repast, a captive.”

The pastime was well established by the seventeenth century, when English writer and man of leisure Izaak Walton compiled his lengthy treatise and ode, The Compleat Angler. In it he advised every self-respecting fisherman to keep with him at all times “the feathers of a drake’s head” and “other coloured feathers, both of little birds and of speckled fowl.” Whether prehistoric cultures practiced the art of fly-tying is unknown, but surely people have been tricking fish with feathers since the dawn of Western civilization. As a feather-obsessed descendant of strongly piscivorous Norwegians, I knew I had to try my hand at it.

“You know, I’ll need a permission slip from Eliza before I teach you how to fly-fish,” John said when I called him up. Then he laughed, and I could hear him take a long drag on his cigarette. “There’s a kind of obsessiveness that creeps in . . . ”

As a veteran fishing guide, John Sullivan had probably risked a lot of spousal disapproval over the course of his career, aiding and abetting people’s fixations on fish and feathered flies. He led trips for everything from cutthroat to small-mouthed bass, but specialized in the pursuit of steelhead, a sea-run trout so famously elusive that anglers call it “the fish of a thousand casts.” People tell of long days, a season, or even years spent trying to hook and land a single specimen. But for the true aficionado, feeling the tug and pull of a steelhead take a hand-tied fly, and watching it race across the surface of a shallow western river, is an experience well worth waiting for.

John and his family live on the wooded rim of a river canyon in eastern Oregon, not far as the crow flies from my in-laws. It’s sparsely populated country where anyone within driving distance qualifies as a neighbor, and he’d known my wife ever since she was a little girl. Though he’d been a professional guide for more than twenty years and people came from around the world to float rivers with him, he sounded a bit wary about taking on a client with family right down the road.

I assured him that Eliza wouldn’t mind. After all, she had already let me go to Las Vegas and interview showgirls for this book—what was a fly-fishing lesson compared to that? John agreed in the end, but only after determining that I wasn’t a golfer. Every person should be allowed one compulsive hobby, he reasoned, and if I didn’t play golf, then there just might be room in my life for fly-fishing. (I decided not to tell him that my feather research could easily lead me to a golf course, too. Before the advent of rubber and modern synthetics, the best golf balls in the world featured a goose-feather core hand-stuffed into cowhide spheres. Packed wet, they dried into tight, hard little slugs called “featheries” that could travel more than two hundred yards, twice the distance of their wooden predecessors and still a respectable drive on most courses.)

I arrived at the Sullivan residence on an unusually chilly spring afternoon, with rainsqualls roiling up the canyon in broad, dark waves. John’s boat sat in the yard on a trailer, tightly tarped against the weather. Trout season was open, he explained, but heavy rains had “blown” all the rivers. Instead of drifting downstream somewhere learning to cast, we retreated inside to concentrate on fishing’s most fundamentally feathery aspect: the craft of tying flies.

“You have no idea what you’re getting yourself in to,” he chuckled and started spreading gear across the dining room table: two steel vices with narrow, toothed clamps and rotary arms, boxes of hooks, bobbins of thread, three pairs of Dr. Slick scissors (curved, straight, serrated), a dubbing spike, a whip finish tool, chenille, beads, tinsel, and various shades of ribbing. And then there were feathers. It was only a small portion of his supply, enough to make the few training flies he wanted to show me, but the table held dozens of loose plumes, flight feathers, and bags of colorful fluff. There was the entire brindled hackle of a rooster, as well as plumage from at least a half-dozen species, from goose and turkey to pheasant and teal. And every style bore its own fly-tying nickname: grizzly, badger, marabou, parachute, biot, cape, or saddle. A hen feather dyed an eye-popping Day-Glo yellow was “Hanford chicken,” named for the famous nuclear weapons site alongside Washington’s Columbia River. Certain high-quality feathers bore the name of a famous breeder, like “Hoffman grizzly,” “Herbert hackle,” “Metz saddle,” or “Conranch stem.” The specialty feather business can be lucrative, with the finest rooster skins selling for hundreds of dollars each. They’re bred for specific traits—a pliable rachis and barbs that splay out evenly when wrapped. The resulting birds look as pampered as show dogs, with long, ornate plumage that gains attention far outside the fly-tying community. At Yale’s Peabody Museum, Rick Prum had shown me a stuffed and mounted “Herbert Miner Cream Badger,” a cock bred for fly-tying, proudly displayed among the most beautiful wild birds in the world.

The lesson passed quickly as John walked me through everything on the table, explaining each piece of equipment and showing me how the feathers could be tied and twisted around a hook shaft to mimic the wings, legs, or bodies of particular insects. A wiry, fit man of middling years, he had a salt-and-pepper beard and the permanently tanned face of a lifelong outdoorsman. He got interested in tying flies “the same way most people do—when I saw guys catching fish with them!” Though John insisted that he wasn’t an expert, he belied that claim all afternoon with his wealth of detailed knowledge about the history, methods, and minutiae of feathers and fishing. He spoke with a combination of professional interest and an enthusiast’s zeal, but stopped well short of the monomania he had warned me about. John has the natural curiosity of a philosopher, and our conversation veered regularly into points of geology, soil chemistry, meteorology, botany—topics likely to cross one’s mind on slow floats through arid western canyons and the thousand casts between fish.

“Now you’re going to tie a Silver Hilton,” he informed me, and quickly demonstrated the steps, twirling thread, black chenille, silver tinsel, rooster hackle, and bits of turkey feather onto a shiny black hook braced in the vice. My attempt didn’t go quite so smoothly, but fly-fishing had taught John great patience and he bore with my clumsy winding, unwinding, and rewinding until finally giving the fly his seal of approval: “I’d fish with that.”

What lay before us was a fuzzy black body with a feathery ruff and shiny stripes, trailing two plumed wings and a tail. “With a dry fly you’re trying to imitate an insect caught on the surface of the water,” he explained, and pointed out how the barbs of the rooster hackle stood out in a spray of points that maximized surface area and kept the fly perched lightly on top of the water. It was touch points and surface tension all over again, but with a twist: dropping these feather barbs into just the right current would make them twitch and jiggle like the legs of a struggling bug.

Outside, the rain had let up, and rays of sunlight angled across the deck. A large hummingbird feeder dangled from the roof beam, and soon Rufous and Calliope Hummingbirds began arriving in droves, taking advantage of the break in the weather to fuel up on the sweetened water. I caught flashes of iridescent green backs and the brilliant crimson of a throat patch and couldn’t help wondering how their feathers might look to a trout, staring up from a streambed at some bit of unimaginable fluff drifting by in the stream.

Before we called it quits, John gave me a tour of his fly collection. “This is really only a part of it,” he said, pulling out box after box, each divided into dozens of tiny compartments. The bins held a dizzying array of bright, hooked baubles, as if the hummingbirds had come inside and arrayed themselves neatly in plastic trays. The obsessiveness John warned me about began to make more sense as he rattled off name after name and showed me the subtleties within each pattern. Here were muddlers, nymphs, streamers, skunks, poppers, rubber legs, duns, Hiltons, agitators, wogs, and articulated leeches, just to name a few. They ranged in size from wisps smaller than a fingernail to giant hot-pink fuzz balls as big as a boiled egg. Each design could have any number of color and texture variations—brown hackle or black, teal feathers or Mallard, a chenille body or one of rabbit hair wrapped around thread and teased with a needle. Feathers featured prominently in almost every fly—from delicate wings and tails to body fluff or long streamers dangling back from the hook. The attention to detail was phenomenal—the “Copper John” included tiny silver balls meant to mimic the air bubbles some insects carry with them underwater. “Honestly, some of these I don’t even fish with,” he admitted. “I just tied them because they look cool.”

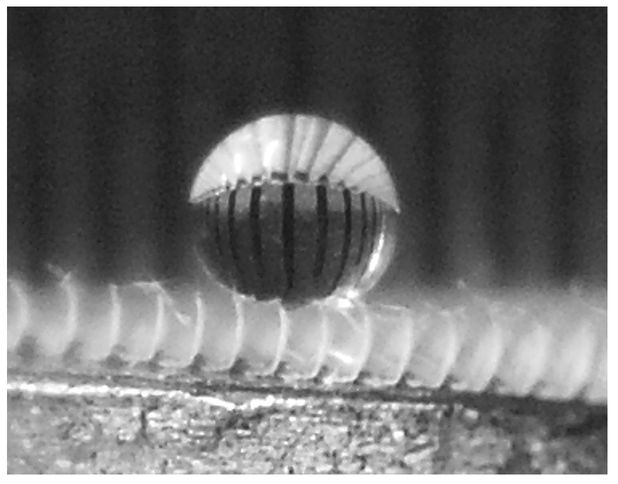

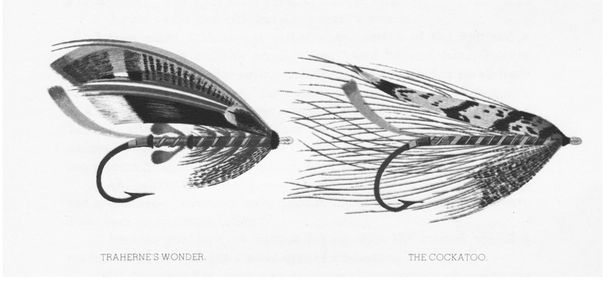

Perusing John’s handiwork gave me a real sense of the art and craftsmanship involved in tying flies. He downplayed his own skills, however. “This is nothing. If you really want to see feathers, you need to check out the old Atlantic salmon patterns!” He directed me then to several lavishly illustrated books devoted to the famed English fly-tiers of the late nineteenth century. The period marked one of sportfishing’s greatest heydays, a time when angling for Atlantic salmon was in vogue with Victorian gentlemen who strove to outdo one another with the extravagance of their lures. And just as the broad reach of empire made a world of feathers available to adorn hats, so too did fly-tiers have access to a limitless variety of colors and textures. Their creations looked less like mock insects than some exotic aviary, where the feathers of parrots, peacocks, jungle fowl, kingfishers, toucans, ostrich, and tanagers grew together in wild, hooked sprays. For some patterns, individual barbs from different species were painstakingly teased apart and then melded together to form new multi-hued feather vanes. Like some of John’s favorites, many of these flies were never fished, and vintage collections now command surprising sums at auction. Even modern reproductions can fetch as much as two thousand dollars per fly.

These two nineteenth-century Atlantic salmon flies featured the plumage of more than ten species from four continents, including Mute Swan, Scarlet Macaw, Ostrich, Helmeted Guineafowl, and Red-tailed Black Cockatoo.

For John, though, part of the fun in tying feathered flies lies not in selling them but in giving them away. He sent me home with a double handful of bright patterns designed for Pacific salmon—the cohos, Chinook, pinks, and sockeye that pass by our island each summer en route to their spawning rivers. His gift included tips on casting and how to get the right action from each fly, and then he gave me some parting words of wisdom. Even if I did everything right, he warned, I might not get a bite. “Having the perfect fly is a lot less important than actually getting it in front of a fish.”

A few months later I tried to do just that. With a secondhand fly rod and a borrowed reel, I headed down to the beach at the south end of the island, not far from where I’d released my Common Murre. It was an early-autumn afternoon, warm and bright with sun. The water stretched out across the straits like smooth glass, etched here and there with tide lines and swirls of current. A hundred yards out, Surf Scoters and a Western Grebe dove and surfaced again and again, chasing minnows through the shallows. Eliza and Noah had joined me, and I could see them making their way along the beach, Noah holding her hand and tottering forward eagerly. I assembled the rod, threaded line through the guides, and proudly tied on my very own Silver Hilton. It whistled through the air by my ear as I cast and watched it settle, a speck of fluff drifting on top of the clear, cold water.

If this were a work of fiction, now is when the salmon would strike, taking the fly and surging across the surface in a series of silvery leaps. Of course, that didn’t happen. My chances of actually catching a fish probably suffered from the fact that I don’t know how to cast. Try as I might, I never got the damn fly to go farther than about ten feet in front of me. And after a few attempts I realized that my fly-tying skills weren’t much better. The Silver Hilton had come almost completely unraveled, releasing its feathers and hackle until only a sad wisp of tinsel remained. Clearly, I had a lot more to learn about fly-fishing, but John was right about one thing—I could see how it might get addictive. I put the rod aside for a moment and just stood there, listening to the murmur of waves and the throaty squabbling of the birds. Down the beach Eliza and Noah had found a place to sit in the sun, and I watched them while he busily picked up stone after stone and tried to sneak them into his mouth. If fly-fishing embodies the metaphysics of feathers and water, then the real lesson lies in the reality of where it takes you. And if it could bring me back to the beach for another afternoon like that one, then I’d do it again in a heartbeat.

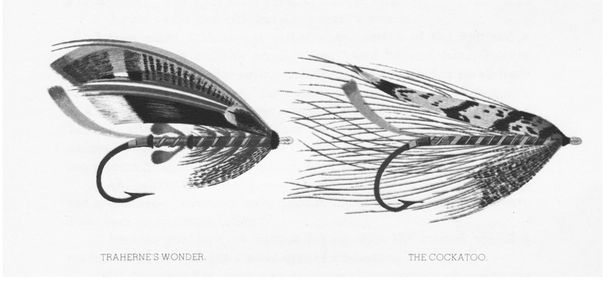

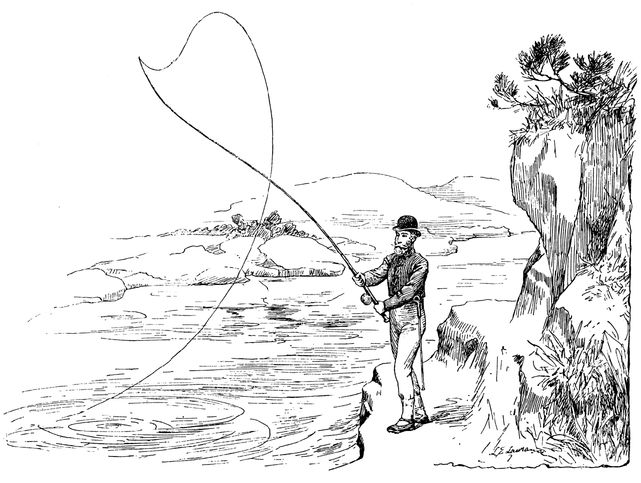

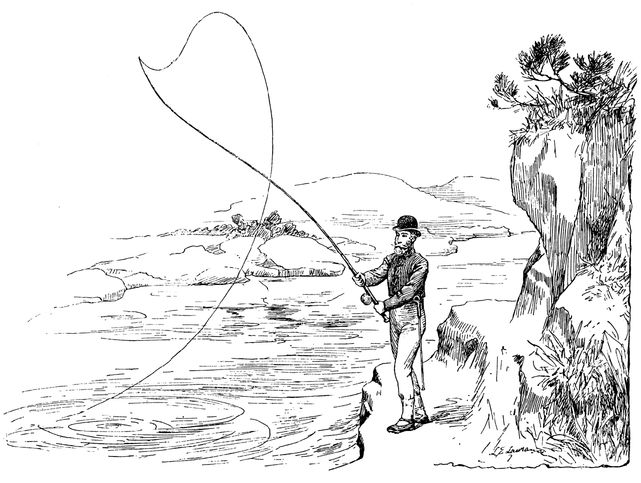

The gentlemanly art of fly-casting.