INTRODUCTION

A Natural Miracle

Lewis stoops to pick up a red-tinged feather lying on the path. He tells me that it belongs to a flicker, points out some of its features—rachis, vanes, calamus—then, giving it to me, says that I now hold in my hand a natural miracle.

—Leonard Nathan,

Diary of a Left-Handed Birdwatcher (1999)

I walked in the lead as the group turned onto a path by the field’s edge, stepping softly in the dew-wet grass. Our shadows stretched westward in the morning sunlight, crazily adorned with binocular shapes, tripods, and the long limbs of spotting scopes. It was the first spring field trip for the local Audubon club. We had started with great blue herons and a pair of yellowlegs patrolling the tide flats and were slowly making our way inland toward a freshwater marsh, where I knew the wood ducks had recently returned from migration. Scattered milk-white clouds scudded through the blue overhead, and the sun felt warm against our faces, a strange but welcome sensation after the rain-soaked Pacific Northwest winter.

My eye caught a flutter of wings and a flash of russet near the fence line. I raised my binoculars, and the bird came into clear focus, standing alert in the short, green grass. “There’s a—,” I began, but my mind went blank. The group stopped, and I sensed everyone turning to look, lifting binoculars, and setting up scopes. It was an obvious bird, really, hardly worth mentioning to a group of pros like this. “By the fence there. It’s a—.” I reached for the name again, but got nothing. A mental dial tone.

“It’s a robin,” the man next to me said acidly, lowering his binoculars. The others turned away too, and there was a moment of awkward silence. I was leading an Audubon Society field trip, and I had just forgotten the name of the American Robin, possibly the most common backyard species on the continent. In the bird-watching community, this was a faux pas akin to an astronomer’s forgetting the name of the Earth. Just then I heard someone say “Warbler!” and the group hurried off up the trail. With my credibility pretty much shot, it was a relief to stay behind and watch the robin.

The subtle rust and charcoal hues of her plumage told me it was a female, and her feathers shone fresh and porcelain smooth in the sunlight. She cocked her head, hopped, and then lunged forward to root at something in the soil. Tilting upright again, she suddenly launched skyward, turning sharply around a fence post and swooping up at an impossible angle to land on an alder branch. Perched there, the robin shook her tail and fluffed up her body feathers before letting everything settle back into place. Then she began to preen, turning and dipping her beak to lift and comb individual quills and vanes, like a fussy housekeeper arranging and rearranging the furniture.

American Robins, by John James Audubon.

I smiled, but who could begrudge her perfectionism? Those feathers impacted every aspect of her life. They protected her from the weather, warding off sun, wind, rain, and cold. They helped her find a mate, broadcasting her femininity to any male in the neighborhood. They kept out thorns, thwarted insects, and, above all, gave her the skies, allowing a flight so casually efficient that our greatest machines seem clumsy in comparison. Abruptly satisfied with her plumes, the robin dropped from the branch and set off over the field, wings parting the air in quick, certain strokes. I lowered my binoculars, far behind the Audubon group now, but glad to have been reminded of a natural miracle, feathers, as common around us as a robin preening and taking flight.

On any given day, up to four hundred billion individual birds may be found flying, soaring, swimming, hopping, or otherwise flitting about the earth. That’s more than fifty birds for every human being, one thousand birds per dog, and at least a half-million birds for every living elephant. It’s more than four times the number of McDonald’s hamburgers that have ever been sold. Like the robin, each of those birds maintains an intricate coat of feathers—from roughly one thousand on a Ruby-throated Hummingbird to more than twenty-five thousand for a Tundra Swan. Lined up end on end, the feathers of the world would stretch past the moon and past the sun to some more distant celestial body. Their exact number is unknowable, but one thing is certain: from the standpoint of evolution, feathers are a runaway hit.

Animals with backbones, the vertebrates, come in four basic styles: smooth (amphibians), hairy (mammals), scaly (reptiles, fish), or feathered (birds). While the first three body coverings have their virtues, nothing competes with feathers for sheer diversity of form and function. They can be downy soft or stiff as battens, barbed, branched, fringed, fused, flattened, or simple unadorned quills. They range from bristles smaller than a pencil point to the thirty-five-foot breeding plumes of the Ongadori, an ornamental Japanese fowl. Feathers can conceal or attract. They can be vibrantly colored without using pigment. They can store water or repel it. They can snap, whistle, hum, vibrate, boom, and whine. They’re a near-perfect airfoil and the lightest, most efficient insulation ever discovered.

Standing there, watching my robin, I was hardly the first biologist enthralled by a feather. Natural scientists from Aristotle to Ernst Mayr have marveled at the complexity of feather design and utility, analyzing everything from growth patterns to aerodynamics to the genes that code their proteins. Alfred Russel Wallace called feathers “the masterpiece of nature . . . the perfectest venture imaginable,” and Charles Darwin devoted nearly four chapters to them in Descent of Man, his second great treatise on evolution. But the human fascination with feathers runs much deeper than science, touching art, folklore, commerce, romance, religion, and the rhythms of daily life. From tribal clans to modern technocracies, cultures across the globe have adopted feathers as symbols, tools, and ornaments in an array of uses as varied and surprising as anything in nature.

At Chauvet Cave in southern France, there is a Long-eared Owl carefully etched into the soft stone of the ceiling. Simple deft lines show the bird looking backward over its feathered shoulder in an unmistakably owlish posture. The image is one of thousands, a minor piece in the collection of petroglyphs and pictographs that make Chauvet, Lascaux, and other nearby caverns a treasure trove of prehistoric art. Haunting and evocative, their ancient animals, designs, and figures are crafted with such skill they moved Pablo Picasso to lament, “We have learned nothing in 12,000 years.” In fact, the artwork at Chauvet dates back more than 30,000 years, making that small owl the world’s oldest known depiction of a bird.

Although artifacts from the period include delicate bird-bone needles, flasks, beads, and pendants, individual feathers are rare in these early cave paintings. Archaeologists believe that ancient hunters used feathers, too, for ornamentation and as brushes for their ocher paints. By the late Stone Age, feathered headdresses and fletched arrows appeared regularly in rock and cave art from Europe to the American Southwest to the deserts of Namibia. Already, people had co-opted feathers for uses both practical (to make an arrow fly true) and deeply cultural (as prized adornments for ceremony and status). Their varied, often vibrant colors made feathers an obvious choice for decoration. Before modern pigments, what other medium offered everything from the beige and umber of pheasants to the bright iridescence of sunbirds, motmots, and parrots? In time, feathers would spawn a global industry, clothe kings and courtesans alike, and define the height of fashion from Paris to New York. The use of feathers for fletching marked a similarly intuitive leap, from flight observed to flight intended. Indeed, their durability and aerodynamic structure would inspire engineers and inventors from da Vinci to the Wright brothers. The consistent appearance of feathers in myth and ritual, however, points to deeper mysteries.

A Long-eared Owl at Chauvet Cave, southern France.

When Emily Dickinson wrote, “Hope is the thing with feathers / that perches in the soul,” she echoed an age-old sentiment linking feathers and bird flight with a sense of portent, longing, and the spirit. In ancient Rome, official fortune-tellers called augurs based their predictions on the behaviors of birds or on patterns seen in their feathers, bones, and viscera. These bird oracles held great sway, influencing major decisions in politics as well as private life, and even today we recall the past importance of augury when we inaugurate presidents or speak of an auspicious occasion. Syrians, Greeks, and Phoenicians divined omens from the cooing of doves, and mystics from many traditions have described the soul or the path to enlightenment in avian terms. To the Sufi poet Rumi, the human spirit was alternately a parrot, a nightingale, or a white falcon on a spiritual journey to God: “When I hear Thy drum . . . my feather and wing come back.” In central Asia, the Dolgan people described the souls of children as tiny birds perched in the Tree of Life, while shamans from South America to Mongolia have described their trancelike states as “riding the wind.” Near-death experiences invariably feature a disembodied phase, looking downward from a bird’s-eye view, and both Jung and Freud considered flying dreams among the most powerful (though whether they symbolized transcendence or rowdy sex was a point of debate).

To earthbound humanity, the ability to fly is inherently otherworldly, revered for its sheer proximity to the heavens. And if flight is sacred, then birds, wings, and feathers are its most potent symbols, appearing again and again in a dizzying range of rituals, beliefs, and customs. Birds and bird-gods figure heavily in all mythologies, and flight is the jealously guarded privilege giving them access to both the spiritual and the earthly planes. In ancient Greece, Hermes relied on winged sandals to speed his passage to and from Mount Olympus, but when the mortal boy Icarus flew too high, his wax and feather wings fell to pieces. The Hindu messenger god, Garuda, emerged from an egg with the body of a man and the plumage of an eagle. Flight earned him the honor of transporting Vishnu and gave him eternal advantage over his devious serpent-spirit adversaries, the Naga. Revered by Buddhists as well as Hindus, his wildly feathered visage still adorns the official seals of Thailand, Indonesia, and Ulaanbaatar.

In some traditions, feathers are a symbol of spiritual purity and a prerequisite for an agreeable afterlife. Upon their death, ancient Egyptians believed that the jackal-headed god Anubis would measure the worth of their heart, and the soul it contained, against the weight of a feather. Those found in balance entered the pleasant kingdom of Osiris. But when the scales tipped wrong, Anubis flung the offending heart into the waiting maw of Amemait, “the Devourer,” a slavering hippo-lion-crocodile beast that crouched at his feet. In the Peruvian Amazon, the Waorani people also faced a feathery judgment at death, as described by ethnologist Wade Davis in his book One River: “Each Waorani has a body and two souls. . . . [T]he one lodged in the brain ascends to the sky where it meets a sacred boa at the base of the clouds. If and only if its nostrils have been pierced and decorated by the finest of feathers can the soul enter heaven. If turned away, it falls back to earth and is consumed by worms.”

The connection between feathers and the sacred did not stop with shamanism or ancient mythologies but found firm footing in the great monotheistic faiths as well. Christianity, Islam, Judaism, and even Zoroastrianism all share a belief in angels, higher spiritual beings that serve as intermediaries on the path toward unity with God. Over the centuries, the depictions and descriptions of angels have been surprisingly consistent. They feature clearly recognizable human figures augmented by the addition of certain features. And what was added? Just what was given to the human form to symbolize an elevated, angelic state? More hair? Scales? A coating of sticky amphibian slime? No, ever since Vohu Manah first appeared to Zoroaster, Michael to Moses, and Gabriel to Muhammad, angels have come equipped with great feathered wings. And the feathers are diagnostic—these are not the leathery, batlike appendages featured on demons or the devil.

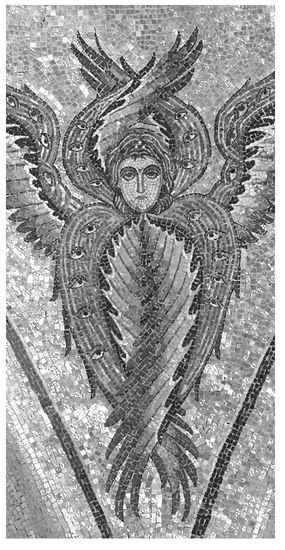

Like Hermes before them, angels used their gift of flight to pass from heaven to earth and back again, often bearing divine tidings. For some, their wings and feathers formed an elaborate pedigree, a sign of status. The chubby little angel haunting a Renaissance mural might boast only two short, stubby wings, while 6, 36, or even 140 pairs appear in various depictions and descriptions of the archangels. At the highest sphere, a seraphim’s feathers were said to resemble peacock plumes, adorned with hundreds of all-seeing eyes. Texts like the New Testament’s Psalm 91 even attribute feathers directly to the Almighty: “He shall cover thee with his feathers, and under his wings shalt thou trust: his truth shall be thy shield and buckler.”

Mosaic of a six-winged, elaborately plumed seraphim, from the twelfth-century Chapel of the Angels at Mont Sainte Odile, Alsace, France.

Truly, the human fascination with feathers is as rich as their natural history. Any thorough exploration must span the sacred and the secular, the practical and the fantastic, from science to myth, culture, and art. Feathers give us insights into evolution and animal behavior but also provide a unique perspective on the history of human belief and ingenuity. Several main themes quickly emerge, providing a framework for the chapters of this book. Evolution explores the contentious mystery of feather origins—where did they come from, and why? Fluff investigates the amazing insulating quality of feathers, from tiny birds in an ice storm to the down in a mountaineer’s parka. Flight reveals how feathers opened up the skies, and Fancy tells the exotic story of allurement, from birds of paradise to showgirls on the Vegas Strip. A final section, Function, investigates how feathers continue to evolve, both in nature and in the myriad additional ways they’ve been adapted for human use. Throughout the book we meet the creatures and characters that bring the story of feathers to life, an eclectic cast of birds, dinosaurs, professors, milliners, inventors, explorers, and more.

As a writer, my job is to keep you turning the pages of this book, but as a biologist I encourage you to put it down once in a while. If you do, you’ll soon find aspects of the story very much alive in the world around you. My wife remembers her grandmother saying, “You’re never more than three feet from a spider.” Even the bestkept home hosts scores of them, tucked into dark nooks and corners or hiding behind the walls. Well, you’re never far from feathers, either. If they’re not stuffing your pillows and parkas, they’re covering every bird in every forest, field, backyard, suburb, and cityscape. You’ll find feathers and their influence in fashion magazines, airplane wings, fishing lures, ballpoint pens, and fine art, but above all in the birds, those commonest of creatures so casually adorned with miracles. Go outside and watch them every chance you get. Look closely. You won’t be disappointed.