Sunday morning, I was packing my duffel bag when Wally called.

“Jessup! I’ve got great news! I think I may have found a wrestling gig for you!”

I gasped. “You did? Where?”

“You know that lucha libre flyer we saw at Casa Guanajuato? Well, I checked out their website. The promoter’s name is Santiago Reyes. Anyway, I wrote to him and sent him your video. He wants to know if you can meet with him today at one o’clock.”

Wally’s announcement was both a joy and a letdown. I was reminded of a writing activity my second-grade teacher gave us, called “Fortunately/Unfortunately.” We had to write about a fortunate thing that happened to us, then counter it with something unfortunate.

Fortunately, I got a dog for my birthday. Unfortunately, it ran away. Fortunately, I found it. Unfortunately, it had been hit by a car. Fortunately, it was still alive. Unfortunately, our vet was out of town.

Fortunately, there’s a promoter who may want to book you. Unfortunately, he runs a lucha libre promotion.

I didn’t follow Mexican wrestling. For one thing, the shows were in Spanish. Also, the style was too acrobatic for my taste. To me, the wrestlers were more interested in performing high-flying spots than in telling a story.

“I wish I could, Wally,” I said. “But like I told you yesterday, I’m swamped with homework. I’ve got to get back to school. I’m just about to leave.”

“Come on, Jessup, this could be a huge break for you,” she said. “Extravaganza de Lucha Libre airs their shows on YouTube. Think of the exposure you’d get. You’d be seen by thousands of people from across the country, maybe even around the world.”

After everything I’d been through, I didn’t have any real hope that something like that could happen to me. But since Wally had gone to the trouble of contacting the promoter, I felt obligated to accept the invitation.

“All right, tell him I’ll be there.”

“You write to him,” she said. “I’ll text you his email address.”

“No, it’d be better if you answered him,” I said. “That way, the promoter will think you’re my agent. And I’d like for you to go with me to be my spokesperson.”

What I really meant was that I was afraid the promoter couldn’t speak English, and I didn’t want to make a fool of myself by stumbling through my limited Spanish.

“Okey doke,” she said. “Chicken!”

Wally knew me too well to be fooled.

I told my parents I had decided to stay in San Antonio awhile longer, and that I’d go to church with them, but that I was having lunch with Wally.

At church, I prayed for God to help me with my wrestling career. I didn’t know if He was listening, because in order to become a wrestler, I’d need to deceive my parents. But like they say, there’s no harm in asking.

Lord, You gave me this body, these skills and this desire for a reason. I know You do things in Your own time, and I don’t mean to rush You, but could You please reveal what You have planned for me real soon? And can You please help my parents be understanding, so they won’t be mad at me when they find out? Amen.

After the service, I raced to Wally’s house. She was waiting for me at the bottom of the steps.

My GPS took us to the Guadalupe County Center, a large metal structure in an open field, with a gravel road that led up to it. A yellow roadside sign with a flashing red arrow pointing toward the entrance, said in black lettering: ¡EXTRAVAGANZA DE LUCHA LIBRE! ¡HOY A LAS DOS!

The grassy parking lot was already beginning to fill with cars and pickups, and people were lined up outside the building, waiting to go in.

“I don’t know about this place,” I told Wally. “It looks kind of rank.”

“You wrestled in a bar, so don’t start acting bougie,” she chided me.

We cut through the line and went inside. Two women were sitting by the door, selling tickets. Wally told them we had an appointment with Santiago Reyes, and they let us in.

The interior of the building was much more elaborate than I would’ve imagined. It was huge, much bigger than the Factory, and a far cry from Capital City Wrestling and the Chaparral Bar & Grill. LED flood lights with moving heads bathed the room with an array of colors, amid the blare of Latin techno music. The ring stood in the middle of the floor and was surrounded by rows of aluminum bleachers.

The place could easily seat three thousand people. Judging by the fans sitting down or walking about, and the line out-side, at least half of the seats would be filled by the start of the show.

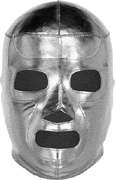

A concession stand was stationed along a wall where customers could buy hamburgers, french fries, nachos, elotes and different kinds of tacos, in addition to soft drinks and beer. A rolling cotton candy cart was parked next to it. A vendor at a table was selling lucha masks, T-shirts and wrestling action figures. At another table, two masked luchadores were peddling photos of themselves and autographing them. Wally asked one of them where we could find Santiago Reyes. He pointed to the wrestlers’ framed entranceway across the room.

A heavyset security guard with a black Extravaganza de Lucha Libre T-shirt was standing in front of it, arms folded over his chest. Wally told him that Santiago Reyes was expecting us. He poked his head through the curtains and announced, “Jefe, hay alguien aquí que quiere hablar con usted.”

A moment later, Santiago Reyes stepped out. He appeared to be in his late sixties, but was fit for his age. His graying hair was combed back, and he had a nicely trimmed graying beard. He wore a black, short sleeve guayabera and black slacks.

“Buenas tardes. ¿Cómo están?” he greeted us and shook our hands.

We introduced ourselves. Then he said, “Morúa. That’s an unusual name.”

Good, he speaks English, I thought.

“Would you by any chance happen to be related to Dr. Wallace Morúa, who used to work at Southwest General Hospital in San Antonio?” he asked Wally.

“Yes, sir. He was my dad. But I never knew him. He died when my mom was pregnant with me.”

Mr. Reyes nodded. “I remember when the accident happened. Lo siento, Wally. Your papi was a good man. He was my doctor. I used to tease him that I was funding his vacations because it seemed like I was going to him every year when I was wrestling. He did surgery on both my elbows, my shoulders, my knees and my hip. The only reason I was able to wrestle as long as I did was because of him. If you ask me, your papi was the best orthopedic surgeon in the country.”

“Thank you. It’s very kind of you to tell me that,” Wally said.

This was unexpected. All of a sudden, I felt I had some clout. I added to it, saying, “By the way, my father is Mark Baron, the Angel of Death.”

“¿De veras?” Mr. Reyes said, smiling. “That’s right, you told me your last name’s Baron. I haven’t seen Mark in a long time. How’s he doing?”

I had prepared an answer in case he knew my father. “Good,” I said. “I did my training at the Factory with him, but I decided not to wrestle there because I didn’t want the other wrestlers to think that my father was showing favoritism toward me.”

“Buena idea,” he said. “I admire that.”

“But Jesse has worked at the Texas Roundup Rasslin’ promotion in Austin,” Wally said, without elaborating. “Now he wants to try lucha libre for a while.”

I was so glad I’d brought her with me. I thought it was funny, though, that she referred to me as Jesse. As long as I’d known Wally, she’d always called me Jessup. I never asked why. I just accepted it as part of her quirkiness.

“Well, I must say that I was very impressed by your demo video, Jesse,” Mr. Reyes said. “Your papi trained you well. I like your ring attire, too. Where did you get it?”

I told him about Shirley Washington and how Wally had designed it for me.

“You know, when I saw your match, I sensed that there was something special about you,” he said. “And now that I’ve learned that the Angel of Death is your papi, and that Dr. Morúa’s daughter came up with the idea for your wrestling name and gear, I’m beginning to believe that fate has brought us together. So if you’re interested, I’d like to book you for next Sunday.”

Wally squeezed my hand and smiled at me. I was too shocked to smile back.

“Okay,” I said softly.

“The pay isn’t much, only thirty dollars a show, to start. More, if you move up. Is that all right?”

That was the same amount of money my father paid his rookies. “Yes, sir, it’s fine.”

Mr. Reyes took a business card from his wallet. “Text me your email address. I’ll send you some paperwork to fill out. Email them back to me as soon as you can.”

While I was doing that, he told the security guard to call someone from the back named Gerónimo.

The security guard disappeared behind the curtains and returned with a muscular man with black hair tied in a bun. He wore a red, sleeveless, Gold’s Gym T-shirt and white sweat pants.

“Gerónimo Chávez, te presento a Jesse Baron y su amiga, Wally Morúa,” Mr. Reyes said. “Jesse es luchador.”

Gerónimo shook our hands. “Mucho gusto.”

“Nice to meet you, too,” I said.

“¿Háblas español?” he asked me.

I made a side-to-side hand gesture. “Más o menos.”

Mr. Reyes then said something else to him in Spanish. I didn’t catch it all, but I understood enough to know that he was telling him I was going to be his opponent next week.

“¿Eres rudo o técnico?” Gerónimo asked me.

“I’m sorry, I . . . I don’t understand,” I said.

“Es un rudo,” Wally interjected. She would explain to me later that a rudo is a heel, and a técnico is a baby face. She must’ve told him I was a rudo because of her preference for heel wrestlers.

“Well, on Sunday, I want you to wrestle as a técnico,” Mr. Reyes said. “Gerónimo’s known in our show as a rudo.”

I told him I’d be glad to do it. Gerónimo excused himself and returned behind the curtains.

“Does he speak English?” I asked Mr. Reyes.

“Más o menos,” he said, mimicking my side-to-side hand gesture. “Now, most of the time, when I hire a new talent, I like to put him in tag-team matches to cover up any weaknesses he might have. But I see star potential in you, Jesse. I want to push you as a singles wrestler.”

The deal was getting sweeter by the minute.

“I know that you have some wrestling experience, and I’ve heard a lot of good things about the Ox Mulligan Pro Wrestling Factory,” he said. “But lucha libre is different from American wrestling. I know because I’ve wrestled in both styles. So let me suggest that you join my lucha classes. They’re not very expensive, only fifty dollars a month. We meet here every Tuesday and Thursday, from seven till nine.”

“Thank you, sir, but I can’t make it,” I said. “I’m a full-time student at UT, and I’m bogged down with school work.”

“Hmm. Well, it’s not a requirement,” he said, although his tone made me wonder if my push was tied to the training.

He went over some ideas for my match, including making it a best two out of three falls. Then he said, “As you know, in lucha libre, your mask is sacred. It’s part of your mystique. Our fans must never see you without it. So have it on when you get here and when you leave.”

I promised him I would.

“All right, enjoy the show, and I’ll see you Sunday. Be here by twelve at the latest.”

I thanked him, but said we couldn’t stay because I needed to get back to Austin. I had a paper due the next day that I hadn’t even started.

During the interview, I kept my emotions in check to avoid being crushed by another rejection. But outside, Wally and I happy-danced and laughed giddily.

Then out of the blue, I burst into tears. One second I was celebrating, the next, I was boohooing like a baby. I felt as if a gigantic burden had at long last been lifted off my shoulders.

Wally took me lovingly in her arms. “It’s finally happening, Jessup,” she said. “Next week at this time, the world is going to witness the birth of a new wrestling legend . . . Máscara de la Muerte!”