Chapter 8:

The Defense of Sackets Harbor

In the months following incursion by the British, the tiny lake port of Sackets Harbor, in upstate New York, developed into the largest American Great Lakes base. With its strategic position, superb natural harbor and abundant resources, it was destined to become the center of military and naval operations for the northern theatre of the war. But it would not become so without a good deal of courage and sacrifice.

After eight years of mortal combat, England finally defeated Napoleon. This freed up British troops for the invasion of the United States. The Earl of Bathhurst, British Secretary of Colonial Affairs, issued the following secret order to Governor General George Prevost, calling not only for the containment and dismemberment of the U.S., but also for the complete destruction of the Sackets naval base:

From Earl Bathhurst, 3rd June 1814

Reinforcements allotted for North America and the operations contemplated for the employment of them.

SECRET

Downing Street

3rd June 1814Sir,

I have already communicated to you in my dispatch of the 14th of April the intention of His Majesty’s government to avail themselves of the favorable state of affairs in Europe, in order to reinforce the Army under your Command. I have now to acquaint you with the arrangements which have been made in consequence, and to point out to you the views with which His Majesty’s Government have made is considerable an augmentation of the Army in Canada.

The 2nd Battalion of the Royal Scots of the strength stated in the margin (768) sailed from Spithead on the 9th ulto. direct for Quebec, and was joined at Cork by the 97th Regiment destined to relieve the Nova Scotia Fencibles at Newfoundland; which latter will immediately proceed to Quebec.

The 6th and 82nd Regiments of the strength (980, 837) sailed from Bordeaux on the 15th ulto. direct for Quebec.

Orders have also been given for embarking at the same port twelve of the most effective Regiments of the Army under the Duke of Wellington together with the three companies of Artillery on the same service. This Force, which/when joined by the detachments about to proceed from this country will not fall short of 10,000 Infantry, will proceed in three divisions to Quebec. The first of these divisions will embark immediately, the second a week after the first and the third as soon as the means of transport are collected. The last division however will arrive in Quebec long before the close of the year.

Six other Regiments have also been detached from the Gironde and the Mediterranean four of which are destined to be employed in a direct operation against the Enemy’s Coast, and the other two are intended as a reinforcement to Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, available / if circumstances appear to you to render it necessary / for the defense of Canada, or for the offensive operations on the Frontier to which your attention will be particularly directed. It is also in contemplation at a later period of the year to make a more serious attack on some part of the Coast of the United States, and with this view a considerable force will be collected at Cork without delay (New Orleans?*). These operations will not fail to effect a powerful diversion in your favor.

The result of this arrangement as far as you are immediately concerned will be to place at your disposal the Royals, The Nova Scotia Fencibles, the 6th and the 82nd Regiments amounting to 3,127 men; and to afford you in the course of the year a further reinforcement of 10,000 British troops.

When this force shall have been placed under your command His Majesty’s Government conceive that the Canada’s will not only be protected for the time against any attack which the Enemy may have the means of making, but it will enable you to commence offensive operations on the Enemy’s Frontier before the close of this campaign. At the same time it is by no means the intention of His Majesty’s Government to encourage such forward movements into the Interior of the American territory as might commit the safety of the force placed under your Command. The object of your operations will be, first, to give immediate protection. Secondly, to obtain if possible ultimate security to His Majesty’s possessions in America. The entire destruction of Sackets Harbor and the Naval Establishment on Lake Erie and Lake Champlain come under the first description. The maintenance of Fort Niagara and so much of the adjacent Territory as may be deemed necessary, and the occupation of Detroit and the Michigan Country came under the second. Your successes shall enable us to terminate the war by the retention of the Fort of Niagara, and the restoration of Detroit and the whole of the Michigan Territory to the Indians. The British frontier will be materially improved. Should there be any advance position on that part of our frontier which extends towards Lake Champlain, the occupation of which would materially tend to the security of the province, you will if you deem it expedient expel the Enemy from it, and occupy it by detachments of the Troops under your command, Always however, taking care not expose his Majesty’s Forces to being cut off by too extended a line of advance.

If you should not consider it necessary to call to your assistance the two regiments which are to proceed in the first instance to Halifax, Sir J. Sherbrooke will receive instruction to occupy as much of the District of Maine as will secure an uninterrupted intercourse between Halifax and Quebec.

In contemplation of the increased force which by this arrangement you will be under the necessity of maintaining in the Province directions have been given for shipping immediately for Quebec provisions for 10,000 men for 6 months.

The Frigate which conveys this letter has also on board 100,000 pounds in specie for the use of the Army under your command. An equal sum will also be embarked on board the Ship of War which my be appointed to convoy to Quebec the fleet which is expected to sail from this country on the 10th or at latest on the 15th instant.

I have the honor to be

Sir

Your most obedient

Humble Servant

BATHURST”

The above secret order was found among the private family papers of Sir Christopher Prevost, 6th Baronet, at his home in Albufeira, Portugal. The order remained secret into the next century. It was discovered at the British Public Records Office in 1922 but lost again soon after. This copy of the order, Sir George’s, was unearthed with the help of Sir Christopher. Boldface is author’s emphasis. *Author’s note.

Prevost also wanted Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont for a winter land route to British Canada, avoiding the frozen St. Lawrence River. He knew that this new country would rival England’s economic power and that whoever controlled the Great Lakes would have possession of Canada. Lopping off the Northeastern states of the U.S. would be a multiple triumph.

Marine Captain Richard Smith had been sent to Sackets Harbor with 100 Marines to guard the yard and naval stores. A naval shipyard surrounding the harbor engaged as many as 3,000 sailors and workmen in what became the first naval arms race in North America. Eventually, almost half of the USMC, 300 Marines, were stationed at Sackets. At this point, Sackets’ “boom-town” nature had caused it to become a dirty, sickly place with waste thrown into the streets. Eight to ten soldiers died of sickness daily and, of the 175 Marines present at this battle, only 30 were fit for combat. Also, Sackets was remote from the highways of American manufacturing—the heavy gear such as hawsers, anchors and great guns (24- and 32-pounders) were brought in by batteaux from New York City via the Mohawk River and Oswego—and it was insecure against weather or hostilities. Similarly, the British naval base at Kingston, Ontario, 35 miles due north on Lake Ontario, had to deal with long supply lines reaching all the way to England itself. A frenzy of shipbuilding ensued on both sides—each side making a larger ship than the enemy’s latest endeavor.

Sackets was to be held at all costs. Commodore Chauncey of the Great Lakes fleet, along with Gen. Macomb, fortified the base in depth. From west to east was the Basswood Cantonment, constructed primarily from basswood, which housed the American regulars: the 9th, 21st, and 23rd U.S. Infantry, the Light 3rd Artillery and the 1st Light Dragoons. Because of the intense cold and wind from Lake Ontario (the snow could reach as deep as eight feet), these troops had the luxury of permanent wood barracks instead of canvas tents. Next was Fort Tompkins with its massive 32-pounder cannon on a six-foot-high, raised swivel. The great gun was manned by experienced cannoneers.

Behind this were the Marine barracks, featuring another rare luxury—fireplaces. The Marines were to fight from these barracks through walls pierced with loopholes for firing. They would be held in reserve until the initial combat at the fort required them to engage in the hottest part of the fight. Next were three gun batteries trained to protect the Navy yard and its around-the-clock ship building.

South of the harbor was Fort Volunteer—the last defense. Macomb had done a splendid job here, creating an impregnable mobile defense in depth just like they did at the battles of Cowpens and Guilford Courthouse during the Revolutionary War. The hospital and the town were just south of the yard. It and the defensive works were ringed with abatis (felled, sharpened trees—the barbed wire of its day). This ring funneled the advancing British right into the killing ground of Fort Tompkins and that deadly swivel.

A total of 5,200 American regulars, dragoons and Marines would be in the fight, not counting the sailors. They were supported by 700 local militia from Jefferson County and the Albany Volunteers. The militia was considered unreliable and usually fled after firing a couple of volleys. All American troops were instructed to load their muskets with a .75 caliber round ball and 3 buckshots. This quadrupled their firepower compared to the British single shot. Both sides were also told to fire at the enemy’s officers.

General Prevost learned through spies that Chauncey was out with the fleet burning York and obliterating Fort George. This would be the perfect opportunity to attack Sackets. The British fleet, sailing from Kingston and commanded by Commodore Yeo, attacked at 3:30 a.m. of May 29, 1813. They towed 50 batteaux and war canoes filled with companies from the 1st, 8th, 100th, and 104th of Foot plus the Gengarries, Voltigeurs (French Canadians from Quebec), and a party of Mohawk and Mississauges. These attackers totaled 1,570 men.

The British thought they were going against weak militia because they’d captured all of Aspinwall’s 175 reinforcements before they landed. With no wind, the British sat in their boats for a whole day as American reinforcements poured into Sackets from all over New York. The troops answered the call just as they’d done against Burgoyne at Saratoga, 36 years earlier.

The British force landed at the north side of Horse Island to form up and easily pushed off the American militia. The American pivot gun opened up on their 33 troop-laden batteaux and columns to devastating effect. The British then marched onto the causeway that connected the mainland. Marching eastward, the British had the rising sun in their eyes and could not see the disposition of the formidable American works. Unfortunately for their fleet, the lake was glass-smooth with no wind, which prevented them from getting close enough to bombard the yard and the village. They eventually had to recourse to using “sweeps” (rowing the ship through oars inserted in the cannon ports) and “hedging” (dropping the anchor way in front of the ship and then winding it to pull the ship forward) to get their ships in closer. Gen. Macomb’s abatis fortifications ringing the base forced the British infantry to take the lake road heading toward the heavily fortified Fort Tompkins. Its lone 32-pounder cannon on a pivot, firing solid shot and grape, was devastating to British boats and infantry in column.

Blinded by white smoke, the Voltigeurs fired a volley into the backs of the 100th of Foot who were formed up right in front of them. After a few volleys from the American militia (who promptly fled), the British met the American infantry formed outside the palisades of Fort Tompkins. After murderous fire, the British were winning the battle and more American militia were retreating on the Adams Center Road. The fighting became very intense with hand-to-hand combat and the British firing into the Marine loopholes—men firing directly into each others’ faces. The British were especially strong in this fight as the poor common soldier had visions of great wealth to be acquired by plundering the town.

British Major Drummond, a fearless leader, was knocked down by an American sniper. His men had implored him to take off his gold epaulettes before the battle, so the bullet struck the metal epaulettes in his pocket, resulting in only a nasty bruise instead of a mortal wound. In fact, every British officer received a wound of some kind during this intense four-hour battle.

Eventually, the British got around to the north side of the fort where Chauncey’s son gave the signal for the munitions and yard to be burned. Later, recriminations would abound as to who actually gave the order. Marine Sergeant Solomon Fisher had been told to have a bonfire ready by the upper barracks as a signal to fire the buildings containing ships’ fittings and the stores captured at York. The Marines were assigned the mission of burning the ship General Pike which was under construction, along with all naval stores, including the Marine barracks, to prevent their capture in case the harbor was taken. When the orders were finally countermanded, the Marines were able to extinguish the fire on the General Pike, thanks to its green wood, but the Marine barracks and storehouse were already ablaze and Capt. Smith’s Marines lost everything. It took months to replace sails and stores to complete the ships. The Americans had mistakenly done what the British failed to do.

However, Prevost, a civilian Governor-General and not a military man, was by nature overly cautious in his command. When his ships could not land cannon, he gave up all hope of overwhelming Fort Thompkins. Only one ship, the Beresford, came up to engage and its effort was minimal due to American counter-fire. Prevost called for a parley in the middle of the battle. When the Americans would not surrender, the British simply left and the Americans did not pursue. In amazement, the Americans watched as the British returned to their boats and quit the battle. Their march turned into a rout and they left their wounded and dead behind along the lake road on which they had advanced.

The British lost 25 percent of their men: 50 killed and 211 wounded. The Americans lost 47 killed, 84 wounded and 36 missing. Lieutenant Colonel Aspinwall’s 9th U.S. Infantry from Massachusetts accounted for most of the casualties—the 9th had fought as hard as their fathers had at Bunker Hill. Private Francis Lawrence, a bounty jumper from Montreal, deserted from the Marines and re-enlisted in the 21st U.S. Infantry for the extra bounty. After the battle, the unforgiving Marine Corps caught up with him and he was shot. USMC Private Elisha Johnson was also shot as a deserter. In addition, 150 Americans were captured at the beginning of the battle when a regimental reinforcement was approaching the harbor during the British landing.

Sackets was one of the toughest running fights of the war. The attack did slow the American shipbuilding effort and relegated the planned U.S. invasion of lower Canada to failure. But ultimately, the British lost much more than they had gained. Again, Marine musketry had proved invaluable in the fight.

If the British had been victorious at Sackets Harbor, they would have gone on to Lake Erie and burned Perry’s fleet being built at Presque Isle at Erie, Pennsylvania, and that loss would have subsequently cost the Americans three territories—Michigan, Indiana and Illinois. During the remainder of the war, Sackets was never attacked again. It was reinforced a third time with additional troops, three more forts and two additional batteries. Eleven vessels ultimately were built there, making up the majority of the Lake Ontario fleet including the 110-gun behemoth New Orleans. Unusual as it might sound, the ships’ cannon and anchors were removed and the ships were sunk in the harbor during the winter for cold storage, then raised in the spring. Sackets Harbor represented the largest American military shipbuilding effort and the largest Marine base in one locale up to that time. It was the first planned army installation in American military history.

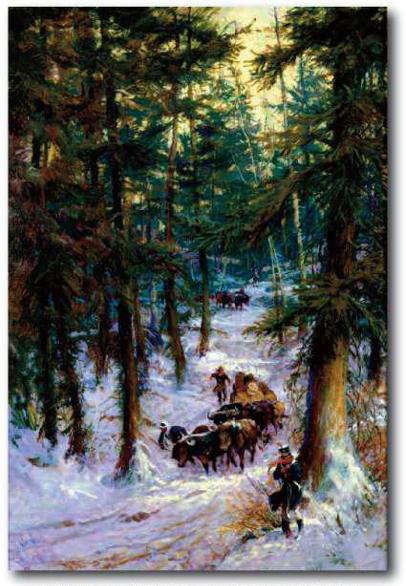

Marine sentry guarding timber supply column for U.S. shipbuilding

Artist: Colonel Charles H. Waterhouse, USMCR