Chapter 14:

The Battle of Lake Champlain

The British defeat of Napoleon in April of 1814 freed up troops in Europe that the British could put to use in America. They planned to finalize the U.S. War of 1812 with a triple-pronged attack on three sides of the United States. The first two attacks were to be feints: first, an attack on New York state thru Lake Champlain; and second, raids on the Eastern seaboard resulting in the attacks on Fort McHenry and Baltimore and the burning of Washington, DC. The real objective was to be the capture of New Orleans, the second-largest American port, and subsequent control of the new Louisiana Territory. With its polyglot foreigners, the city was mistakenly thought to hold little allegiance to the U.S.

The Land Battle. The 15,000 British infantry, led by Sir George Prevost, Governor-General of Canada, were considered the finest infantry of the day. They were ordered to “destroy and lay waste” New York and they outnumbered the Americans four to one. The strategy was for the army to capture the three American forts manned by six infantry regiments in Plattsburgh, capture the state arsenal there, and then bombard the American fleet which would be trapped in a pincer movement between the army and the British naval squadron under Captain Downie. They prepared for the assault on the forts by making scaling ladders from horse racks found in local barns. They were to start the attack on land at the sound of the first broadside from the British Navy.

General Macomb, the American commander, had only 3,500 men remaining, 1,000 of whom were sick. Just a week earlier, Generald Izard had marched the other 4,000 men to Sackets Harbor where another British attack seemed eminent. Macomb knew he was outnumbered by Wellington’s veterans so he decided to use hit-and-run tactics.

Colonel Appling’s 100 riflemen started by felling trees in front of the enemy’s advance and abatising the roads. Thousands of militia began pouring in from Vermont, New Hampshire and more New York counties, recalling how General Burgoyne’s invasion had been stopped 39 years earlier. Groups of 100 to 300 men were sent to impede the British advance and fought three engagements. Captain Aiken’s Company of Volunteer Riflemen, composed of 15 teenage marksmen, attacked a British column. Captain McGlissin, with 50 men, routed an entire 300-man rocket battery. Four large U.S. artillery batteries held up the British at two bridges whose planks were taken up and used for barricades. Hot shot (heated cannonballs, previously used only against ships) was fired into a part of the town to drive the British snipers out of the houses.

The British Army was getting across the Saranac River and had the upper hand when the American side suddenly sent up a loud cheer that the sea battle was won. This discouraged Gen. Prevost, who ordered an about face and headed back north, infuriating the British Army. A great quantity of munitions and provisions were abandoned as they retreated back to Montreal. Prevost felt that without the Navy’s support, and with the American fleet on his flank, he could not sustain a deeper incursion into New York. He had proved to be a better governor than a General.

The Naval Battle. Commodore Thomas MacDonough, a firebrand, commanded the depleted American naval squadron. Earlier, two of his sloops were captured trying to slow the British advance down the Richelieu River, cutting his force by a third. MacDonough used the same tactic General Benedict Arnold had used at the battle of Valcour Island 38 years earlier. He stationed his squadron on a north/south arc southwest of Cumberland point to await the British attack. In this way, he held the weather gauge—the wind in his favor—while the British had to beat into the wind to maneuver against the Americans.

The U.S. force consisted of four ships—the Eagle, Saratoga, Ticonderoga, and Preble, and ten gunboats, each carrying one or two cannons—for a total of 86 guns. They were manned by 882 sailors and Marines. The Marines performed a number of duties on board. They led all boarding parties and amphibious assaults. They fought on the tops—fighting platforms on the masts—as marksmen, and hurled grenades at the hatches where the powder magazines were stored. They were trained to man the great guns—24- or 32-pounder cannon—in case a cannon crew was taken out. They also provided discipline on board such as sleeping between the officers and crew to prevent mutiny. In this battle, about 200 infantry served as Marine sea soldiers providing musket fire.

The British also had four ships—the Chub, Linnet, Confiance, and Finch, along with ten galleys—for a total of 96 guns and more than a thousand men. Again, the Americans were outnumbered—but the U.S. troops had just learned of the burning of Washington and they were firmly resolved to win this fight.

Commodore MacDonough, a religious man, prayed with his officers before the battle. The American ships, formed in an arc, had their gunboats 40 yards behind them to prevent a rear maneuver. Their north flank was protected by Cumberland Point and to the south by shoals. The British had to come bow-in at them. This way, the American line could rake the enemy first, with the devastating broadside that swept the enemy’s deck from bow to stern.

On the Saratoga, a gamecock’s cage was struck by an opening cannonball. The rooster flew up into the rigging and squawked at the British which spirited the American gun crews. The battle was a horrific fight of ear-shattering broadsides, crashing timber, torn canvas and the screams of dying men. MacDonough’s flagship, the Saratoga, caught on fire twice from hot shot. He waited for the British to close, because the Americans had 32-pound carronades or “smashers,” which were the latest technology but were only effective at close range. MacDonough was knocked unconscious twice, once by a falling boom and again when the decapitated head of a gun crew captain hit him in the face.

The British worked the left and right flanks of the line as ships’ cables were cut and drifted off. Lieutenant Cassin, U.S. Navy, while loading canister of 1-inch balls and bullet bags, had to repel British boarders again and again, but held the right of the line. The British were slaughtered. Their attacking galleys were so decimated that they could barely row away. Three British officers lay down on the deck, covered their ears and cowarded out. Every man on both sides was at the very least wounded.

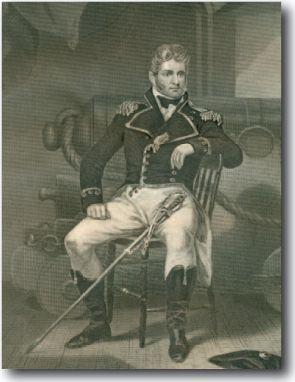

Commodore Thomas MacDonough

Collection of the author

The Saratoga and the Eagle now remained to slug it out with the Confiance and the Linnet. The quoins, or cannon elevating blocks, on the Confiance were not adjusted, causing its broadsides now to fire too high. Captain Downie of the Confiance was killed early by a flying timber. Some cannon were overloaded to the muzzle with shot, making them dangerous and ineffective.

The tactic that won the day for the Americans was MacDonough’s use of “springs.” These were lines that were pre-attached to anchors on the port side so they could not be shot away. When his ship was battered with over 55 hull hits, he came round with those lines to bring about the unused side of the ship to bear, with fresh cannon. The British tried the same maneuver but only came half-way round.

Captain MacDonough’s victory message to Congress read: “The Almighty has been pleased to grant us a signal victory on Lake Champlain, in the capture of one frigate, one brig, and two sloops of war, of the enemy".

The battle cost the British 50 dead and 116 wounded. American casualties were 50 slain and 58 wounded. A Royal Marine who had fought with Admiral Nelson at Trafalgar said, “That battle was a flea bite compared to this fight.” General Macomb, Commodore MacDonough and Lieutenant Cassin were awarded Congressional medals by Congress. Along with 119 other seaman, seven Marines still lie buried on Crab Island today in an unmarked grave. This battle was one of the most important engagements in American naval history. If it had been lost, the U.S. would have been short 33 states.

The above monument now stands on Crab Island, due to the author’s efforts to honor the fallen sailors and Marines at this site.

Courtesy of Ken Roberts.

The War of 1812 taught the U.S. three vital lessons for the future: First, the need for a standing army—never again would the country depend on county militias to fight experienced armies; second, that a series of coastal forts were needed—and built—to protect American port cities from Maine to Louisiana and; third, that there was a need for a bigger Navy with more frigates rather than small-craft gunboats expected to fight against Britain’s 1,000 ships and 110-cannon men-of-war. Even the pacifists saw the need to end experimentation and listen to the professionals.