Chapter 15:

Marine Defense of Fort McHenry

After the burning of Washington, British General Ross wanted next to destroy Baltimore, America’s nest for building swift “clipper-built” privateers. These ships and their crews had cost England over a million pounds in captured cargo. Baltimore was third in U.S. population at this time and was fourth in industry and wealth.

The city appropriated $20,000 for defense and began the job by fortifying the town with 40 cannon. From spring through fall, the city prepared their strong defense in full view of the British fleet, some of whose ships would intermittently raid Chesapeake villages. U.S. General Winder was put in command at Baltimore with 9,000 men. The U.S. Marines were placed in the center of the line to work the great guns.

The British, commanded by Gen. Ross and Admiral Cockburn, landed at North Point, 12 miles from the city. They numbered 9,000 men, including 2,000 Royal Marines. Unwilling to wait for their attack, the Americans marched out of their defenses to meet the enemy. Gen. Ross was killed by two teenage riflemen—Dan Wells and Henry McConas—who were later slain. After a two-hour fight, the American left gave way and the 51st, 39th, and 27th regiments were struck with dismay. The Americans retreated to their fortifications before the city. The British fleet comprising 16 vessels anchored near Fort Carroll.

While the British right was moving on land to Baltimore, their fleet comprising 50 ships entered the Patapsco river on the left to attack Fort McHenry. The fort commanded the entrance to the harbor with its narrow strait. Major George Armistead commanded the U.S. star fort defenses.

On the morning of September 12, 1814, a mass of British frigates, schooners, sloops, bomb-ketches, and bomb vessels moved to within two-and-a-half miles in front of the fort. The bomb and rocket vessels moved in closest to the fortifications on the hill. Their advance into the harbor was blocked by 24 sunken American ships lying between the fort and Lazaretto Point. These ships, scuttled to form a barrier, were later refloated at a cost of $100,000.

The American defenders in the fort and at fortifications in the harbor were comprised of one company of U.S. artillery under Captain Evans; two companies of Sea-fencibles under Captain Bunbury; two companies of volunteer “Washington Artillery” led by Captain Berry; the Baltimore Independent Artillerists led by Lieutenant Pennington; the Baltimore Fencibles; volunteer artillerists led by Judge Nicholson and; a detachment of 600 men from the 12th, 14th, 36th, and 38th U.S. regiments led by Lieutenant Colonel Stewart.

Commodore John Rodgers also led a brigade of 1,000 Marines and sailors. They were composed of survivors of Bladensburg under Captain Samuel Baron; 170 Marines stationed at Baltimore under Captain Alfred Grayson; Marines from the Guerriere under Captain Joseph Kuhn; Lieutenant John Harris with his Marines from Philadelphia and; the Marine artillery with 42-pounders under Captain Stiles.

At 7 a.m. the next day, 11 heavy vessels, five bomb-ships and a rocket ship opened fire on Fort McHenry. Rocket ships were a new invention and their “rockets’ red glare” was used primarily as a scare tactic. A tremendous shower of shells rained down on the star fort but the Americans kept to their posts, imbued with cool courage and great fortitude. U.S. Major George Armistead gamely returned fire, but his shots fell short.

After dismantling a 24-pounder on the fort’s southwest bastion by fire, the British moved three bomb vessels in closer. Now they were in range of U.S. artillery fire. In only half an hour, the British fell back after the rocket ship Erebus was disabled and towed back by smaller boats—but the bombardment of the fort increased until midnight. The British then moved on Fort Covinton and the City Battery manned by the Marines. The British tried to flank the fort by firing rockets and sending 1,250 Royal Marines in barges with scaling ladders to storm the fort. Two barges were sunk by Marine cannon fire and a large number of British were slain. Two hours later the British retreated. After Craney Island, this was the second time that U.S. Marines had pushed a battalion of Royal Marines back into the sea.

The shelling of Fort McHenry continued all night for 24 hours until 7 a.m. From 1,500 to 1,800 shells weighing 210 pounds each were fired. A total of 189 tons of iron burst over the fort, fragments raining down on the garrison. The concussion of the bombs was so great that houses in Baltimore were shaken to their foundations. Four Americans were killed and 24 wounded. A lucky shot fell onto the powder magazine, but fortunately it was a dud. Armistead later admitted that he alone knew that the fort’s magazine was not bomb-proof. He had said nothing for he felt his men would not defend the fort if they knew.

Flag that flew over Fort McHenry

Francis Scott Key, an artillery volunteer, was seven miles away in the Bay on a truce-boat waiting for the release of an American hostage, Dr. Beanes from Upper Marlborough. Beanes had been in a cartel ship, the Minden, negotiating for an exchange of prisoners. After the discussion, Cochrane refused to let him or Key return until after the battle, and they were kept on the Surprise. That morning in the mist, Key was inspired to write the anxious National Anthem because he himself was in a state of anxiety to see “if our flag was still there!” As dawn broke, the fort’s defenders defiantly replaced the weather flag with the soon-to-be “Old Glory,” an enormous 30 by 42 foot American flag, snapping in the face of the departing British.

The British land army was being repulsed in front of the Baltimore fortifications. On the 12th, they lost their general, one lieutenant and 37 killed with 11 officers and 240 wounded. But since the Americans had not struck their flag, the British army planned one last effort—a night attack against Baltimore by way of the York and Harford roads.

An American officer, Colonel Brooke, had a parley with the British commander in front of the city and, amazingly, convinced him it would be futile to continue the attack against Baltimore’s heavy fortifications. The British left at three a.m. on the 14th.

The Americans had lost 24 killed, 139 wounded, 50 prisoners and two guns. On the McHenry side, the Americans lost only four men killed and 24 wounded, mainly by the explosion of the shell on Nicolson’s 24-pounder.

The British fleet turned around and left, to the great delight of the defenders. The fort was intact and Baltimore saved. If the city had fallen, Philadelphia and New York would surely have been burned next.

The Marines and seamen artillery under sailing-master Webster were credited by Armistead as saving both Fort McHenry and the city. The grateful citizens of Baltimore gave the Marines a gift of silver service and Commodore Rodgers proclaimed: “that the brave officers, Marines, and seamen whom I had the honor to command on that occasion did everything in their power for the defense of your city which the peculiar nature of the service and their limited means would allow is true.”

Every year on September 10, Defender’s Day, you can witness the re-enactment of the bombardment of Fort McHenry—a truly stirring event that recreates the feeling of that enormous British bombardment. Perhaps more than any other single battle, the defense of Fort McHenry proved the value of the Marines in assuring American victory over the British.

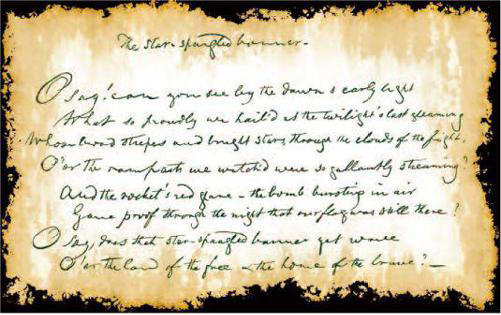

Facsimile of the original manuscript of the first stanza of The Star Spangled Banner.