Chapter 17:

Ambush at Twelve-Mile Swamp

Twelve-Mile Swamp, named for its distance from St. Augustine, Florida, is even now a forbidding area of cypress bogs and palmetto thickets. Through this heavily wooded wilderness, on the evening of Sept. 11, 1812, a ragged column of 20 Marines and Georgia militiamen passed, led by Marine Captain John Williams, a 47-year-old Virginian. His uniform was that prescribed in the 1810 regulations—navy blue coat faced with red, buttoned and laced in front with a gold epaulet on the right shoulder and counter-strap on the left; white vest and trousers with a scarlet sash; black knee-high boots; a sword at his side; and on his head, a cocked hat with cockade and plume.

Williams’ mission was to escort a pair of supply wagons from the main camp of the Patriot Army near St. Augustine to the blockhouse on Davis Creek, about 22 miles to the northwest. He and his detachment had come to East Florida to join an expedition intent on annexing the Spanish province. They feared that the British would use Florida as an advance base for an invasion, and that escaped slaves might inspire insurrection in the southern states.

The Marines, half-starved, ill with fever, and their dress uniforms tattered from months of frustrating shore duty with the Army, were more than a little uneasy as they eyed the surrounding thickets. They were well aware that bands of armed Seminole Indians and runaway slaves were active in the area. Anxious to reach the safety of Davis Creek before sunset, they hurried the blue military supply wagons through the gloomy swamp as twilight deepened.

Suddenly, the woods along the trail erupted with a blaze of musket fire as a large band of Indians and blacks fired a point-blank volley into their column. Williams, his sergeant, and the lead team of horses were downed by the first shots. The wounded captain was quickly assisted off the trail by one of his men.

Distinguished in their blue coats, white trousers, and high-crowned shakos, Williams’ Marines took up defensive positions along the trail and returned fire with their standard-issue 1808 smoothbore, muzzle-loading, flintlock muskets. The badly wounded Capt. Williams watched as Captain Tomlinson Fort, his militia counterpart from Milledgeville, Georgia, took over the command, exhorting the troops to continue the fight until the last cartridge. Eventually, he too was wounded, and ordered a retreat further into the swamp. As the fighting ended, the enemy band destroyed one wagon and drove off in the other, with their wounded inside.

During the night, part of the detachment made its way to the blockhouse while Williams, too severely wounded to be moved, hid himself among the palmetto thickets. The next morning, a rescue force found the Marine captain—his left arm and right leg broken, and his right arm, left leg and abdomen pierced by musket fire. Searching further, they found six more wounded in the brush, in addition to Williams’ sergeant, stripped and scalped.

“You may expect,” Williams wrote to Lieutenant Colonel Marine Commandant Franklin Wharton four days later, “that I am in a dreadful situation, tho’ I yet hope I shall recover in a few months.” Despite being moved to the relative comfort of a nearby plantation house, Williams died on Sept. 29.

The ambush at Twelve-Mile Swamp and the subsequent death of Marine Capt. John Williams proved to be the catalyst which brought an end to an ill-conceived and diplomatically embarrassing American scheme to annex Spanish East Florida by force.

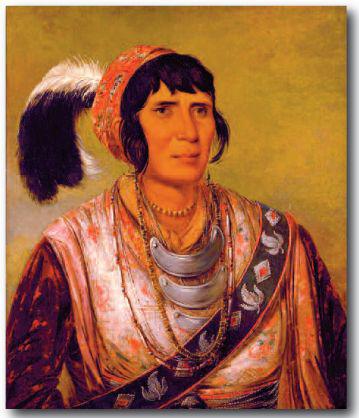

Seminole Chief Osceola (1804-1838)