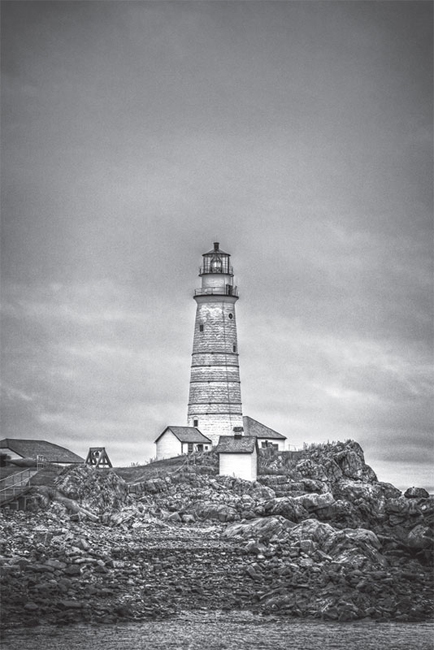

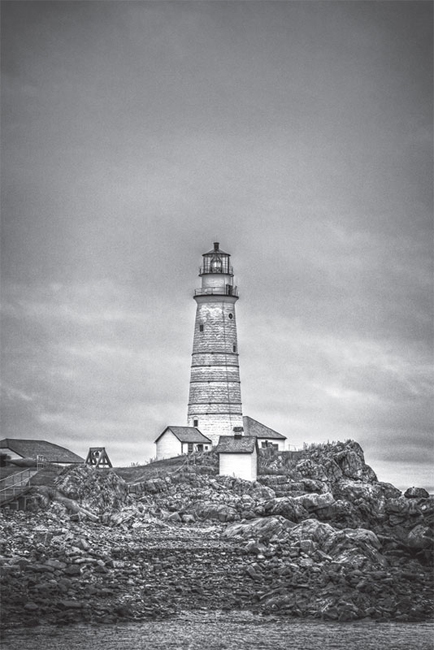

Little Brewster’s historic Boston Light, originally built in 1716, has withstood blizzards, erosion, fires, lightning, shipwrecks and ghosts. Photo by Frank C. Grace.

Chapter 4

LIGHTHOUSE HAUNTS

Jeremy D’Entremont, author and historian for the American Lighthouse Foundation, joked that people can find at least one ghost story associated with each of the dozens of lighthouses scattered throughout New England if they dig deep enough.

“Just imagine living at an isolated, offshore lighthouse all year round, through storms and all kinds of extreme conditions,” he told me. “Such an existence could easily cause the imagination to play tricks. But I do believe that many of these stories are at least partially true. Some people think that the ocean is a good conductor of paranormal energy. I’m not sure about that, but lighthouses are among the oldest structures in many of our coastal communities and their human history is dramatic and full of emotion.”

Haunted lighthouses? Yes, he’s heard several strange-but-true tales from the various towers. “Many of these stories seem to point to a lighthouse keeper of the past who continues to ‘keep watch,’ even after his death,” he said.

D’Entremont, the go-to expert for New England lighthouses, said he even had a close encounter himself while giving a tour at his home haunt for fifteen years, Portsmouth Harbor Light in New Castle, New Hampshire.

“One day I was giving a tour for a married couple in the middle of the afternoon,” he told me. “We were at the top of the stairs, in the watch room. I was leaning against a ladder and telling them some of the history of the place.” It was the start to any ordinary tour.

“As I was talking, a low, gravelly, male voice from my right said, ‘Hello,’” D’Entremont continued. “I stopped, and I asked the couple if they heard anything. The husband in the group swore he also heard a man say, ‘Hello,’ whereas his wife didn’t hear a peep. We looked down the stairs and outside, and there was nobody else anywhere near the lighthouse. A few other people have had similar experiences.”

Little Brewster’s historic Boston Light, originally built in 1716, has withstood blizzards, erosion, fires, lightning, shipwrecks and ghosts. Photo by Frank C. Grace.

D’Entremont has been on multiple paranormal investigations and has heard a few spine-tingling stories from former keepers and visitors over the years. “Once I was talking on the phone with a man who was a Coast Guard keeper at an isolated lighthouse in Maine. He laughingly said, ‘You know, some keepers thought there were ghosts at the lighthouses.’ I thought he viewed the idea as a joke.”

However, the keeper’s tone quickly turned serious. “One time, I was outside late at night, and I looked over at the lighthouse tower,” he told D’Entremont. “I saw a woman sitting on the railing on the top of the tower. I know I saw her, but I know there was really no woman there. I can’t explain it.”

Of course, D’Entremont said extreme isolation could factor into each alleged ghost sighting. “I definitely think living at a remote, isolated location can play tricks on your imagination,” he continued. “I have no doubt that some ghost stories were based on strange, but natural, sights and sounds experienced by the keepers and their families. I also think that keepers and family members shared stories, and they are prone to exaggeration as they’re passed down.”

As far as the lighthouses in Boston Harbor are concerned, D’Entremont said he’s heard quite a few stories about the three-hundred-year-old Boston Light. “Dennis Dever, the Coast Guard keeper in the late 1980s, told me that his radio in the boathouse would change itself from a rock station to a classical station,” the historian recalled. “He also said that one time he was looking out a window in the keeper’s house toward the lighthouse tower and he saw a man standing in the lantern room. Alarmed, he ran to the tower and ran up the stairs—and there was nobody there. He told me he was positive he saw someone.”

D’Entremont offers a lecture on the haunted lighthouses of New England. He said folklorists, like the late, great Edward Rowe Snow, helped shine a light on the preservation of these remote, offshore lighthouses he’s grown to love. “The stories he told drew attention and inspired many people—including me—to become interested in the islands, forts and lighthouses of Boston Harbor,” D’Entremont said. “I was lucky enough to meet him a couple of times, and Edward Rowe Snow was one of the big influences of my life. He was a larger-than-life character who did everything with passion.”

Does he think Snow fabricated the sometimes over-the-top tales of ghostly damsels in distress and other fearsome phantoms allegedly haunting Boston Harbor? “I don’t think he made up the stories, but I think he took some of them and ran with them—particularly the Lady in Black,” D’Entremont continued. “In his early books, Snow stated that he couldn’t guarantee that any part of the story was true. But he definitely popularized it, and it became one of his signature stories.”

D’Entremont said the biggest hurdle facing the historic lighthouses in Boston Harbor has little to do with the ghosts. It’s about preservation. “It’s a struggle,” he emoted. “I would urge anyone who cares about lighthouses to volunteer or to donate to an organization like the American Lighthouse Foundation. Every dollar helps.”

The lighthouse aficionado continued: “The next couple of decades will be very telling for offshore lighthouses, especially when you add rising sea levels into the mix.”

The one story that still creeps out D’Entremont centers on the Penfield Reef Light in Fairfield, Connecticut. “A few days before Christmas in 1916, the head keeper, Fred Jordan, left to row to shore to visit his family. A sudden storm blew in, and he was capsized and drowned within sight of the assistant keeper at the lighthouse.”

D’Entremont said Rudolph Iten, the assistant, became the next head keeper. “A few days later, he saw a ‘gray, phosphorescent figure’ go down the stairs in the keeper’s house. He followed, but there was nobody there. When he went to his desk, he found that the logbook had been pulled off a shelf and was open to the day when Jordan had died,” he recalled, adding that Iten had multiple face-to-face encounters with the ghost of the fallen light keeper years after the initial incident.

Is D’Entremont a believer? Yes. “Lighthouse keepers had tremendously strong emotional ties to their lighthouses, so it’s not that much of a stretch for me to think a keeper’s spirit might choose to remain at a lighthouse or to make an occasional visit,” the expert confirmed.

BOSTON LIGHT

There’s an inexplicable mystique radiating from Little Brewster’s Boston Light. Celebrating its three-hundred-year anniversary in 2016, it’s located approximately nine miles offshore from downtown and dates back to 1716. Boston Light was rebuilt in the eighteenth century after the redcoats torched the original structure during the Revolutionary War. It’s the second-oldest working lighthouse in the country, and its ninety-eight-foot-high tower has seen almost three centuries of tragedy, starting with the death of the light’s first keeper, George Worthylake, who drowned alongside his wife, daughter and two other men when their boat capsized a few feet from the island’s rocky terrain in 1718.

Boston Light, nestled on Boston Harbor’s Little Brewster Island, celebrated its three-hundred-year anniversary in 2016. Photo by Frank C. Grace.

The ghosts from the Boston Light’s early days have captivated the imagination of the city’s land-bound inhabitants for years. A young Benjamin Franklin, then an up-and-coming printer, penned a ballad about the Worthylake incident called “Lighthouse Tragedy,” which he later dismissed as “wretched stuff ” but joked that it “sold prodigiously.” Boston Light’s second keeper, Robert Saunders, met a similar fate and drowned only a few days after taking the job. The tower, which originally stood at seventy-five feet, caught fire in 1751, and the building was damaged so intensely that only the walls remained. The British, angry that the colonists had tried to disengage the beacon during the revolution, apparently destroyed Boston Light in 1776 while heading out of the Boston Harbor. It was rebuilt in 1783 but witnessed several more tragedies, including two shipwrecks, the Miranda in 1861 and the Calvin F. Baker in 1898, which resulted in three crewmen freezing to death in the rigging.

In addition to the onslaught of natural disaster, one keeper in 1844 set up a “Spanish” cigar factory, carting in young girls from Boston and claiming that the stogies sold in the city were foreign imports. Captain Tobias Cook’s clandestine cigar business was quickly fingered as fraudulent and shut down.

President John F. Kennedy legislated that the Boston Light would be the last manned lighthouse in the country. It has been inhabited for almost three centuries, even when the tower was automated in 1998. One island mystery, known as the Ghost Walk, refers to a stretch of water several miles east of the lighthouse where the warning sounds from the tower’s larger-than-life foghorn cannot be heard by passing ships. For years, no one has been able to scientifically explain the so-called Ghost Walk’s absence of sound, not even a crew of MIT students sent in the mid-1970s to spend an entire summer on the island.

However, talk of the paranormal has trumped the island’s Ghost Walk mystery. “It has withstood blizzards, erosion, fires, lightning, shipwrecks and ghosts,” mused a report in the April 29, 1999 edition of the Boston Globe, which profiled Little Brewster’s Chris Sutherland from the U.S. Coast Guard. Apparently, the petty officer noticed tiny human footprints in the snow while keeping the light in the late ’90s. “I’m not saying it’s a ghost,” he said, “but I don’t know. In the past, there were kids out here, light keepers’ families. There were shipwrecks along the rocks.

A former Coast Guard engineer who lived on the island in the late ’80s, David Sandrelli, told the Globe that there have been reports of a lady walking down the stairs. Also, he said that crew members stationed on Little Brewster would hear weird noises in the night but would dismiss them, saying, “It’s just George,” an allusion to the ghosts from the Worthylake tragedy.

Sally Snowman, who was the first female keeper at the last occupied lighthouse in the country, told the Globe in 2003 that she had a few “just George” moments during her stint on Little Brewster. “I won’t say if I believe or don’t believe in any ghosts on the island,” she said. “Let’s just say I’ve heard plenty of stories. Some strange things do happen out here, like the fog signal, which works on reading moisture in the air, going off at 3:00 a.m. on a star-filled night. That’s fun because you have to walk across the island to shut that sucker off. That can be weird.”

Little Brewster’s mascot, the black Labrador Sammy, reportedly had a close encounter in 1999. “He would stand up, run out of the room for no reason and was shaking all over,” recalled a former keeper, Gary Fleming. “It really does get spooky. You have plenty of time here, and if you let your mind go, you can freak yourself out,” Fleming said, adding that he believes in the supernatural.

Snowman echoed Fleming’s comments about the canine mascot’s odd nightly ritual. “He’s been out here six years, and at dusk every night he barks and barks,” she mused. “We call it the Shadwell Hour, after the slave who died.”

So who’s Shadwell? Mazzie B. Anderson, a woman who was stationed with her husband on Little Brewster in 1947, recalled hearing footsteps when no one was there and watching the foghorn engines magically start themselves when her husband was ill. She also heard maniacal laughter followed by the sobs of a female voice yelling, “Shaaaadwell, Shaaaadwell!” It turns out that Worthylake, his wife and their youngest daughter, Ruth, capsized near the island, and the eldest daughter, who was left behind with her friend Mary Thompson, reportedly witnessed her family’s demise. In addition to servant George Cutler and friend John Edge, the capsized vessel included an African American slave.

According to lighthouse historian Jeremy D’Entremont, another person, rarely mentioned in the history books, was on the island that day. “The first keeper, George Worthylake, died in November 1718 along with five other people when their canoe capsized,” he said. “One of the people who died was the slave. It’s not necessarily well known that there were two slaves at Boston Light at that time—there was also a woman named Dinah.”

Some believe the postmortem screams heard on the island belong to the forgotten African American woman who watched the horror unfold off the shore of Little Brewster. “Somehow the canoe capsized and all went overboard,” wrote Anderson in the October 1998 edition of Yankee magazine. “The African made a valiant attempt to save all hands, but failed. The young girl was the last to go under, still calling his name. No one survived.”

The name of the courageous African American slave? He was known as Shadwell.

File under: anniversary ghost

LONG ISLAND HEAD LIGHT

Added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1987, the Long Island Head Light got its start in 1819 as a twenty-foot-high stone tower. After falling into disrepair and surviving a series of storms, the original Inner Harbor Light, as it was initially called, was demolished and replaced three times. The second version of the Long Island lighthouse was made out of cast iron. It was moved to its current location on the northeast end of Long Island in 1901 and was recrafted in stone to avoid the wayward gunshots from the troops preparing for battle at Fort Strong.

The Long Island Head Light is home to the Woman of the Scarlet Robes legend. The wailing woman spirit is said to have been fatally wounded during the American Revolution and buried in a makeshift grave on the island. Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Print Department.

The historic structure’s light was extinguished in 1982 and then relit in 1985 after years of neglect. The Coast Guard made an attempt at refurbishing the unmanned lighthouse in 1988 but was not able to finish. Its present-day shell can be seen peeking from the thicket on the extreme tip near the ruins of the fort.

In addition to the ghostly lore involving the Woman in Scarlet Robes, which was discussed in the “Asylum Haunts” chapter, several notable stories involving the tip of Long Island have become harbor legend.

The first death at the lighthouse was in October 1825. Keeper Lawrence, a veteran of the War of 1812, sustained injuries during the Battle of Fort Erie and died inside the stone structure. However, Lawrence wasn’t the last keeper to have a visit from the grim reaper while living at the Long Island Head Light.

Keeper Edwin Tarr died on January 18, 1918 “while sitting in his chair looking over the water,” reported Edward Rowe Snow in The Islands of Boston Harbor. The funeral was held in an old building attached to the lighthouse. It was a frigid January in Boston Harbor and Snow said a sleet storm enveloped the island so that it became an “ice-coated drumlin.” Tarr’s four pallbearers were a bit surprised by the slippery Long Island terrain as they carried the coffin out of the building.

“Suddenly one of the soldiers skidded, the coffin went down onto the ice, and the four men were forced to grasp the handles of the coffin and get aboard as the casket began traveling down the hill over the ice,” Snow continued. “Thirty seconds later the casket—which had become a toboggan—ended its weird trip down the hill at a point just near the head of the wharf.”

According to Lighthouse Friends, Tarr was the last full-time keeper on Long Island. “Following Tarr’s death, several custodians cared for the light until it was automated in 1929,” the website confirmed. “The light was decommissioned in 1982, but that decision was soon reversed. The light was refitted with a solar-powered optic, visible fifteen miles away, and relit in 1985. Since then some necessary repairs have been performed to the tower, which is now mostly obscured by trees that have been allowed to grow up on the island.”

The late Pierce Buckley, known for his work at the Boston Public Library, capsized in a canoe off the shores of Long Island in 1890. Snow said Buckley and his friend held on to the overturned vessel for dear life and feverishly paddled to the lighthouse to beg the keeper for help. “Reaching the island, they climbed up the hill leading to the lighthouse, but the keeper of Long Island Light told them in no uncertain terms to get off the island,” recounted Snow. “The boys, shivering and wet, furled their sails, climbed back into the canoe, and paddled off toward South Boston where they finally arrived more dead than alive.”

Because of its proximity to three long-gone drumlins—Bird, Apple and Governors Islands—the Long Island lighthouse also had a bird’s-eye view of a handful of forgotten ghosts from Boston Harbor’s past.

The now flattened-out Governors Island boasted what is believed to be Boston’s first ghost sighting. The island’s owner, John Winthrop, told the tale of three sailors who were in Boston Harbor on January 18, 1664. According to Snow, the harbor started to churn and a set of strange lights emerged from its frozen waters and the energy shot out “sparkles and flames.” The sailors were understandably surprised and mortified when the orbs transformed into the shape of a man.

Snow said the water spirit tried to lure the three sailors into his underwater abyss, saying, “Boy, boy, come away, come away.” Luckily, the three men fled the scene and didn’t succumb to the sinister sprite’s demands.

Apple Island, which was razed in 1946 to become the runway of East Boston’s Logan International Airport, was home to the ghosts of two star-crossed lovers. According to Snow, a girl who was descended from the city’s early governors was murdered by a group of hoodlums living on the island. “The young girl’s sweetheart at once suspected that the men were the cause of his lady’s death,” wrote Snow. “Nothing was heard from him for weeks, until a friend finally disclosed that he had gone to the island and joined the robber band in order to find out the details of the girl’s death.”

Snow claimed that a fisherman spotted a lifeless body hanging from an elm tree on Apple Island. When the authorities investigated, they found it was the man who had tried to avenge his girlfriend’s death. “The ghosts of the two were said to be still walking up and down the shores and around the great elm in 1900,” Snow continued, adding that the spirits of the star-crossed lovers haven’t been heard from or seen in years.

Bird Island, which was also absorbed by the airport in East Boston, was one of the two islands in Boston Harbor where the hanged bodies of pirates were showcased as a way of warding off potential witches, rakes and rogues. The other was the allegedly haunted Nix’s Mate. One tall tale from Bird Island’s past involves events that occurred during the winter of 1634. A group of men were heading to Boston after a visit to Deer Island. It was exceptionally cold, so the crew stayed overnight and weathered the storm on Bird Island. By morning, Boston Harbor had frozen over and the stranded men could walk safely on the sheets of ice and even managed to trek back to the mainland.

Meanwhile, the now vacant Long Island Head Light stands as an eerie sentinel, protecting the secrets of the inner harbor’s haunted past. In 2015, the bridge connecting Long Island to Moon Island was dismantled, displacing hundreds of homeless men and women who considered Boston’s largest city-run shelter their home. Camp Harbor View, which welcomes legions of inner-city kids to the island every summer, continued after the Long Island bridge was destroyed, but the program’s future is in jeopardy.

“Boston may have been a beacon on a hill, but it cut its teeth by the sea,” wrote Christopher Forest in Boston’s Haunted History. “While Boston’s waterways have been home to a flurry of activity, they have also been home to an array of local lore. The famed Boston Harbor Islands alone are a virtual treasure trove of ghostly tales.”

Two if by sea? Because of its water-bound landscape, much of Boston’s spooky maritime past has been lost at sea. However, a few ghostly tales have surfaced over the years, like long-forgotten messages in bottles from Boston Harbor’s frigid and apparently haunted waters.

File under: harbor’s harbinger

MINOTS LEDGE LIGHT

Haunted lighthouses for sale? Only in New England. Minots Ledge Light, located about one mile offshore from Scituate and Cohasset, was auctioned off in October 2014 to a private bidder—identified later as Boston-based philanthropist Bobby Sager—for a mere $222,000.

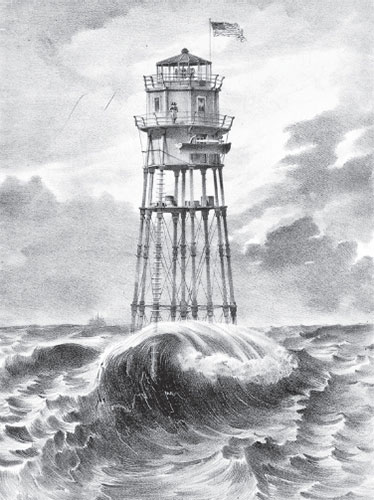

Lighted for the first time on January 1, 1850, Minots was built in response to the record number of maritime disasters in the southeast corner of Boston Harbor. In fact, the rocky terrain surrounding Minots Ledge was responsible for the destruction of forty vessels in the 1830s, including a heartbreaking incident involving the death of dozens of Irish immigrants en route to Boston to start a new life in America.

The lighthouse’s initial promise was short-lived. In April 1851, the original wooden structure was lost at sea when a torrential, nor’easter-like storm literally ripped the tower off its ledge. Designed by the Corps of Topographical Engineers, it was built to be pinned to the ledge. Apparently, the Corps’s approach didn’t work.

The first Minots Ledge Light was built between 1847 and 1850 and was destroyed by a major storm in April 1851. Joseph Wilson and Joseph Antoine, the two men stationed at the lighthouse that night in 1851, are believed to be responsible for its alleged hauntings. Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Print Department.

“The residents along the shore remember seeing the flashing beam as late as one o’clock the following morning, but when dawn came the structure had disappeared,” Snow wrote in The Islands of Boston Harbor. “At low tide the jagged edges of the piling, bent and broken, were visible a few feet above the ledge. The two keepers had been lost.”

Joseph Wilson and Joseph Antoine, the two men stationed at Minots that dark and stormy night in 1851, are said to be responsible for its alleged hauntings. Several websites claimed that the keepers left a message in a bottle, saying: “The lighthouse won’t stand over to night. She shakes two feet each way now.” Also, there were reports of what sounded like gibberish echoing near the lighthouse. It was a mystery until a group of fishermen from Portugal deciphered the postmortem warning of “ficar longe.”

Jeremy D’Entremont, author of The Lighthouse Handbook: New England, told Haunted Boston Harbor that even the phantoms of Minots Ledge Lighthouse were wary of New England’s notoriously capricious weather. Storms seemed to exacerbate the activity inside the dark tower. And based on regional ghost lore, Wilson and Antoine continued to keep watch even in the afterlife.

“The stories at Minots Light relate to the deaths of two young assistant keepers in 1851. The most common thing you hear is that the spirit of one of the men is seen on the ladder on the side of the lighthouse, yelling, ‘Stay away!’ in Portuguese when bad weather is approaching,” D’Entremont explained. “There’s also a story, told by Edward Rowe Snow, that one of the keepers heard a tapping in the walls that seemed to be a response to his tapping of a pipe on a table. It was noted that the keepers in the original lighthouse—the one that fell in 1851—would signal to each other between floors by tapping on a stove pipe.”

Of course, the severe isolation of Minots Ledge Light might have heightened tensions in the tower. “One assistant keeper was driven mad by living in rooms without corners and another threatened to kill the head keeper. And to make bad matters worse, there were ghosts lurking about,” reported folklorist Lee Holloway. “More than one keeper reported the presence of two phantom figures in the lantern room, and unexplained knocks and the ringing of a phantom bell were often heard in the middle of the night. Many lighthouse personnel swore that on calm, sunny days, if one looked at the reflection of the tower in the water, the images of the two drowned keepers would appear in the doorway.”

Several historic New England lighthouses, including the allegedly haunted Minots Ledge Light, were put on the auction block recently. D’Entremont said it’s a huge task to maintain these beloved beacons. “Auctioning a lighthouse to the public is basically a big roll of the dice—you don’t know what you’ll get,” D’Entremont explained. “Dave Waller, who bought Graves Light, is one of my favorite lighthouse owners. He is extremely hard working and creative, and he’s doing a wonderful job. Nick Korstad down in Fall River, owner of the Borden Flats Light, is another example of a successful owner who has opened his lighthouse to the public. But some other cases haven’t worked out so well.”

Boston Harbor’s Graves Light set a record when it was sold at auction for a hefty price tag of $933,000. But is it haunted?

Multiple keepers of Minots Ledge Light reported the presence of two phantom figures in the lantern room, mysterious knocks and the ringing of a bell that is often heard in the middle of the night. Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Print Department.

Dave Waller, the new light keeper at Graves Light, said his million-dollar investment is ghost free “despite a name that suggests otherwise,” he joked. “As far as we can tell, Graves isn’t haunted. No one recently working out there, former keepers or published reports even hint of it,” Waller confirmed. “What makes you think it’s haunted?”

Because of its macabre name, visitors believe the lighthouse somehow marked the watery graves of the hundreds who died in Boston Harbor. Located on the outermost rocks near the harbor’s North Channel, the tiny ledge was named after Thomas Graves, who could have been a British admiral or a colonial-era merchant. No one knows the truth. However, the 113-foot-tall structure was featured in the 1948 film The Portrait of Jennie. It also witnessed one of the more bizarre Boston Harbor tragedies when the City of Salisbury freighter, nicknamed the “zoo ship” because of its cargo of exotic animals, sank in 1938.

Speaking of harbor tragedies, the two assistant light keepers believed to haunt Minots Ledge Light were recently honored. The Coast Guard cutter Abbie Burgess searched for remnants of the fallen 1851 lighthouse during an underwater excavation in 2007. The crew did find iron beams believed to support the base of the original lighthouse.

The Coast Guard also lowered a plaque into the watery abyss next to the ledge in memory of Joseph Wilson and Joseph Antoine. The plaque was attached to a five-thousand-pound stone and was sunk thirty-one feet into the bay. The bronze memorial read: “These brave men gave the last full measure of devotion to their duty to keep the light burning.”

A lone musician played “Taps” as the bronze commemorative plaque was lowered into the water. There hasn’t been a report of the ghostly cries begging sailors to “stay away” in years. Minots Ledge has become a local legend of sorts on Valentine’s Day due to its automated light. It’s now known as “Lover’s Light,” because the one-four-three flash is the numerical count for “I love you.”

File under: jeepers keepers