6 • Little Fauss and Big Halsy

As productions sanctioned by the success of Easy Rider, the youth-cult road movies Five Easy Pieces, Two-Lane Blacktop, and Vanishing Point have all been retrospectively enshrined in the New Hollywood canon. Part of the reason for this critical reappraisal stems from specific aesthetic outcomes that resulted from the departure from standardized Hollywood production practices. As subsequent generations of critics and scholars retrospectively elevate the historical standing of films on the basis of their departure from typical aesthetic and industrial norms, there is an inherent risk that the canon can become distorted, idealized, and fundamentally unrepresentative. Beyond this handful of now-canonical youth-cult road movies, many more entries in the post–Easy Rider cycle have not yet been reassessed. One such film is Little Fauss and Big Halsy. Released within a month of Five Easy Pieces, Little Fauss enjoyed none of the success of Rafelson’s work, and its director, Furie, failed to graduate to the ranks of auteurs.

Despite its adherence to the post–Easy Rider youth-cult road movie cycle trends, Furie’s Little Fauss and Big Halsy failed to tap the wide commercial audience galvanized by Hopper’s earlier film. Little Fauss made less of an impact upon release than either Vanishing Point or Two-Lane Blacktop, and the subsequent decades have done nothing to rehabilitate its legacy. The film remains virtually unknown and inaccessible, given its lack of an official DVD release, its scarcity on VHS, and the unlikeliness of any but the most obscurantist curator programming it for a film festival, cinémathèque, or late night television broadcast. Nevertheless, while Little Fauss failed to act as a launching pad for the careers of Furie, screenwriter Charles Eastman, and fledgling star Michael J. Pollard, it does feature one bona fide movie star: Robert Redford, playing defiantly against type. Redford’s presence and his attempts to distance himself from the film after its initial commercial failure are indicative of the ways that stardom was shifting in the burgeoning New Hollywood, both at the point of production and in the process of reception.

Sidney J. Furie

Little Fauss director Sidney J. Furie enjoyed something of a globetrotting early career, which took him from his native Canada to the United Kingdom and finally to the fringes (but never the inner depths) of Hollywood. Furie’s career trajectory stands in contrast to directors such as Rafelson and Hopper, whose opportunities to continue making idiosyncratic, thematically consistent works declined as the New Hollywood moment receded. Both Hopper and Rafelson eventually reemerged after a period of directorial absence with more generically conventional films that nonetheless lack the distinctive thematic and stylistic unity of their 1970s works (Five Easy Pieces, The King of Marvin Gardens [dir. Bob Rafelson, Columbia Pictures, 1972], and Stay Hungry; and Easy Rider, The Last Movie, and Out of the Blue [dir. Dennis Hopper, Discovery Films, 1980] forming rough parallel trilogies of sorts).

Furie, on the other hand, occupies territory closer to that of Richard C. Sarafian, or perhaps even Don Siegel: that of the dependable genre director who, at the moment of New Hollywood transition, made a handful of strange, hybrid works that blurred the distinctions between conventional genre outings and the new American youth film, art cinema cycle. By the mid-1970s each of these directors had returned to comparatively “straight” genre filmmaking, yet Sarafian’s Vanishing Point and Siegel’s The Beguiled (Universal Pictures, 1971) and, arguably, Dirty Harry, demonstrate the strange things that can happen when the commercial imperatives of Hollywood genre cinema meld with the subversive characteristics of the new youth films.

By the time he began work on Little Fauss, Sidney J. Furie was already an established filmmaker. Having relocated from Canada to the United Kingdom, he acquired an impressive five directorial credits in 1961, for the horror films Dr. Blood’s Coffin (United Artists) and The Snake Woman (United Artists), During One Night (Gala Film Distributors), Three on a Spree(United Artists), and the Cliff Richard vehicle The Young Ones (Paramount Pictures). The following year he directed the teddy-boy exploitation title The Boys (Gala Film Distributors), a genre that he returned to two years later with The Leather Boys, which melded biker-exploitation with British kitchen-sink realism and homoerotic subtext. Furie’s energetic visual style was brought to bear on his subsequent film, The Ipcress File (Universal Pictures, 1965), a hip, nihilistic revision of the still-novel James Bond franchise, which had recently been inaugurated with Dr. No (dir. Terrence Young, United Artists, 1962). In The Ipcress File, Furie’s harsh daylight-noir-inspired look served as a fitting environment for Michael Caine’s down-at-heel Harry Palmer, a stark cinematic contrast to the glamorous, lushly cinematic environs inhabited by Sean Connery’s Bond.

The Ipcress File was a significant enough international breakthrough to permit Furie’s passage to Hollywood, where he helmed a series of genre entries: the western The Appaloosa (1966) for Universal; the spy thriller The Naked Runner (1967), starring Frank Sinatra, for Warner Bros.; and finally, the 1970 courtroom drama The Lawyer for Universal, which would be the first lead role for future Vanishing Point star Barry Newman. In 1970 an overworked and underappreciated (by his own reckoning) Furie spoke candidly with Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine, expressing his dissatisfaction with the Hollywood machine and his place in it. Of his experience in Hollywood, Furie said, “I knew before starting each of these pictures that they wouldn’t work, but I couldn’t quit. . . . I’m just a naïve, stupid guy.”1 He hoped that his next film, Little Fauss and Big Halsy, would better represent his aesthetic tastes and grant him the creative freedom he sought within the industry.

Repackaging Easy

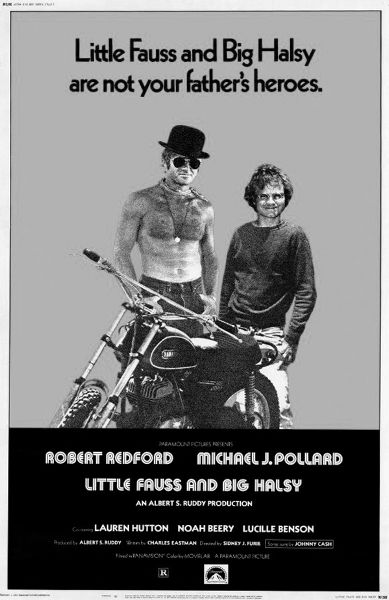

Perhaps the post–Easy Rider youth-cult road movie cycle would enable Furie’s professional transformation. More so than Vanishing Point and Two-Lane Blacktop, Little Fauss and Big Halsy is an overt repackaging of the elements of Easy Rider. The parallels between Furie’s and Hopper’s films are numerous: the central fixation on motorcycles (rather than cars, as in the Sarafian and Hellman films), the conspicuous branding of a rock ’n’ roll soundtrack (in the case of Little Fauss and Big Halsy, a slate of original songs by Johnny Cash), the presence of a screenwriter with a strong literary pedigree (Terry Southern in the case of Hopper’s film, and Charles Eastman on Little Fauss), and the casting of a buddy/antagonistic duo in the two lead roles, consisting of a conventional “star” figure and an off-kilter off-sider (Fonda/Redford, against Hopper/Pollard). Little Fauss and Big Halsy also adopts the kind of generational aniums that is central to Easy Rider and makes it a main feature of its promotional identity, with its tagline reading, “not your father’s heroes.”

Little Fauss and Big Halsy was written by Charles Eastman, brother of Carole (Five Easy Pieces and Hellman’s The Shooting—the latter of which featured an uncredited Charles as an extra). Charles Eastman’s truncated career follows the same halting path mapped out by Bobby Dupea in Carole’s Five Easy Pieces; in fact, in an LA Times obituary piece following Charles’s death in 2009, Robert Towne speculated that Charles Eastman may have been a model for his sister’s Dupea character.2 According to the same obituary article, Charles Eastman began his career writing for the stage in the late 1950s, before working as a script doctor and writing a number of original screenplays in the 1960s, which he refused to option to studios unless he could direct them himself. This degree of control was rarely granted to a first-time writer-director prior to the post–Easy Rider Hollywood boom; under the more rigid confines of Classical Hollywood studio production, these creative roles were almost always distinctly detached from one another. Little Fauss and Big Halsy was Eastman’s first feature-length screenplay to be realized. He acquired only two further credits to his name in his lifetime: the Jon Voight boxing picture The All-American Boy (Warner Bros., 1973; Eastman’s only directorial effort, working from his own screenplay), and Hal Ashby’s Second-Hand Hearts (Paramount Pictures, 1981). Eastman’s screenplay for Little Fauss and Big Halsy displays his literary bent, featuring such lyrical scene descriptions as “grey ovals of grazing sheep spot a vast rolling pasture washed in the leaning light of evening.”3 Eastman’s screenwriting also demonstrates his ear for dialogue, such as in a particular truck stop lament delivered by Halsy, which crystallizes the ennui of geographic displacement that Hellman would later make central to Two-Lane Blacktop: “Hey, did you ever notice that you can drive all day and all night, and wherever you stop, it’s the same greasy hamburgers, same fried egg, served by the same fat waitress, it’s just like you never went nowhere at all.”4 Daniel Kremer’s recent biography Sidney J. Furie: Life and Films provides a detailed production history of Little Fauss and Big Halsy’s thirteen-week shoot for Paramount, which included location work on speedways in Arizona, California, and New York. Above all, Kremer stresses Furie’s, Redford’s, and producer Albert S. Ruddy’s “reverence” for Eastman’s screenplay.

Figure 6.1. “. . . not your father’s heroes.” The poster for Little Fauss and Big Halsy trades on intergenerational animus.

The story follows two riders on the dirt bike racing circuit: the mechanically adept but personally aloof amateur racer Little Fauss (played by Michael J. Pollard) and the manipulative, perpetually broke professional racer Halsy Knox (Redford), who meet at a race in Arizona. Fauss has only his parents (Noah Beery Jr. and Lucille Benson’s performances radiating chipper, down-home hospitality) as friends, and he is starstruck by Halsy, who quickly exploits his newfound admirer’s mechanical abilities. Fauss’s overprotective parents do not approve of their son’s friendship with Halsy, and the familial relationship is damaged further when Fauss clandestinely slips away from the family home to tour the national racing circuit with Halsy, who plans to race under Fauss’s name after he himself is banned from competing. Their friendship, which consists of the eager-to-please Fauss acquiescing to every demand of the lecherous, womanizing Halsy, is tested with the arrival of the absurdly monikered Rita Nebraska (Lauren Hutton), who becomes involved with Halsy, spurning the infatuated Fauss. In an attempt to impress Rita, Fauss takes up racing himself, promptly breaking his leg in an accident. The narrative begins to fall apart at this point. Fauss moves back to his parents’ house, and an indeterminate amount of time passes; the fact that Fauss’s father has died in the intervening period is mentioned in the dialogue, but not shown on-screen. Halsy shows up at the Fauss household with a pregnant Rita in tow, but Fauss sends them both away as he single-mindedly trains for his return to racing. Later, Fauss encounters Halsy at a race and nonchalantly reveals that he has been drafted—a single line delivered with such understatement, and which attracts so little reaction from Halsy, that it is easily missed. The two compete in a race together, and the film ends before the winner is decided.

Cinematic Style

Little Fauss and Big Halsy does not adhere to a traditional, causally motivated narrative mode, but nor does it self-consciously subvert generic expectations to the extent of Hellman’s Two-Lane Blacktop or many of Robert Altman’s films of the period. Little Fauss’s opening shot, a long-take wide shot of dust rising as motorcycle racers interminably cross the horizon, could well have come from Hellman’s film, but for the most part Furie’s directorial style hews closer to a classical model, favoring more traditional camera setups and spatially coherent continuity editing. Little Fauss and Big Halsy employs neither the studiously minimal aesthetic of Hellman’s Two-Lane Blacktop nor the stylistic self-consciousness of the more lyrical passages of Easy Rider, Five Easy Pieces, or Vanishing Point. Furie occasionally incorporates a more incongruously cinematic mode of representation, such as in the helicopter shots of Halsy’s truck, or the flash-frames, à la Easy Rider, which introduce Rita Nebraska. Elsewhere, Furie emphasizes the intimacy of the film’s love triangle with tightly framed, widescreen compositions of the three central characters’ faces. The tone of the film’s performances is similarly mixed. The conflict between Little and Halsy offers the dramatic grist of the film, but neither character is sufficiently developed to flesh out the men’s individual lives and personalities. Michael J. Pollard, having played the sympathetic loser C. W. Moss in Bonnie and Clyde, gives a naturalistic performance in the lead as Little Fauss, which is undercut by his occasional overplayed stuttering delivery and the far broader performances of Benson and Beery as Ma and Pa Fauss.5 In the wake of Bonnie and Clyde, Pollard’s potential for stardom perhaps seemed no less likely than that of his cast-mate Gene Hackman, a similarly atypical physical presence. Nevertheless, Pollard’s casting in the lead role as Little Fauss still seems something of a gamble, given his unproven ability to generate the energetic screen presence of a Hackman or Nicholson.

Redford

In contrast to Pollard, Robert Redford came to Little Fauss already something of a major movie star. Redford attracted major attention for his lead role in Barefoot in the Park (dir. Gene Saks, Paramount Pictures, 1967) and established his magnetic, affable, easygoing screen charm with his star-making turn in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969). Redford’s outings in the year of Butch Cassidy’s release—as a highly motivated, competitive skier playing opposite Gene Hackman in Michael Ritchie’s Downhill Racer and as a sheriff hunting Robert Blake’s fugitive Native American in blacklisted-director Abraham Polonsky’s Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here (Universal Pictures)—failed to further commercially consolidate his standing as superstar, and Little Fauss was a transitional film. Clearly the role of Halsy was not a showcase vehicle for Redford’s established screen persona. Halsy Knox is a singularly unlikable character. Viewed in a certain light, Little Fauss functions as a deliberate subversion and deconstruction of Redford’s stardom and golden-boy looks, as Halsy, the loafish cad, relies on his looks and charm to manipulate all those around him.6 Redford, an actor possessing the charisma to anchor a film, should by all rights be the draw-card attraction of Little Fauss, but the film does not treat him kindly. Eastman’s screenplay goes out of its way to paint Halsy in unflattering terms. His entrance into the film involves him covertly stealing sandwiches and hiding them in his motorcycle helmet at a race. He spends much of the film looming on the sidelines of the action, observing as he chews gum or compulsively brushes his teeth, a leering, often shirtless force of teeming masculinity. In a supposedly heartfelt moment of candor, he confides in Fauss that his past sexual partners were “all dogs.” Later in the film, he signifies his romantic interest in Rita Nebraska upon their first meeting by plunging his hands down his pants in what Pauline Kael sardonically noted was “perhaps a cinematic first.”7

Heterosexuality and Homoeroticism

As a work emerging in a cinematic moment that is not exactly known for its sensitive portrayal of female characters, Little Fauss and Big Halsy seems to reserve a particular brand of cruelty for women. The film’s central premise concerns a chauvinistic tug of war between the two male protagonists for ownership of the Rita Nebraska character, a not dissimilar scenario to Two-Lane Blacktop, except that Lauren Hutton’s Rita is afforded none of the agency of Laurie Bird in Hellman’s film.8 The overt sexual politics of Furie’s film are complicated by the undercurrent of homoeroticism that persists throughout the picture, a dimension of the buddy formula that goes unacknowledged in either Easy Rider or Two-Lane Blacktop, but which Furie had already made central to his earlier The Leather Boys. Even predating Furie’s involvement with Little Fauss, the homoerotic motif is suggested by much of the language of Eastman’s screenplay, such as in the scene when Little Fauss brings Halsy home for the first time and the two future rivals bond over a record of motorcycle sound effects, ending with the two men somnolently tangled in a decidedly postcoital embrace:

Removing shoes and socks, jackets, shirts and pants, LITTLE and HALSY tiptoe around the room as though silence would redeem them.

LITTLE gets an idea. He calls for attention with broad drunken gestures. He takes an LP from the shelf and puts it on the phonograph and then before the sound begins he reveals the album face to HALSY, counting on the latter’s bliss.

Sounds of the Grand Prix.

HALSY grabs the album hungrily and settles on the bed in dirty shorts and t-shirt. LITTLE lies on the floor. They face each other enraptured and pick their toes and listen, as though it were Tchaikovsky, to the deafening sound of over a hundred motorcycles . . .

In their euphoria, HALSY and LITTLE FAUSS have slumped in repose and finally sleep as the Grand TT at Sachsen-Ring continues, with German commentary.9

Such suggestive language persists in Eastman’s description of a group of motorcyclists lining up before the race, “stuffed into white workpants so tight a smudged relief of comb and wallet is stamped on every rear, while a small wad in front could be either penis or car keys,” and in a tension-charged exchange late in the film in which Fauss challenges Halsy’s ability to stay erect; both characters are quick to clarify that they are referring to sitting upright in the motorcycle saddle.10 The homoerotic potential of such buddy pairings has lain dormant in the youth-cult road movies stretching all the way back to Easy Rider, but Eastman’s screenplay comes closest to realizing it. Ultimately, the film never pursues this avenue, even as its narrative trajectory suggests that given their inability to recognize their desire for one another, Fauss’s and Halsy’s confused feelings are channeled into the war for the affections of Rita. Thus the film cycle remains stridently heteronormative, despite its implicit homoerotic coding. Three years after a bisexual subplot was vetoed by Warner Bros. in Bonnie and Clyde, Little Fauss and Big Halsy was unable to do much more with similar material, and the aimless air that permeates the closing segments of the film represents another missed opportunity, on the part of both the characters and the filmmakers.11 But this kind of unresolved ending was by this point already a well-established hallmark of the post–Easy Rider cycle.

Marketing and Muted Reception

The marketing materials for Big Fauss and Little Halsy channel the spirit of the youth-cult road movie cycle, stressing a sense of generational conflict. The liner notes of the soundtrack LP specifically invoke the unfashionable western genre in opposition to the motorcycle cult:

They’re not your father’s heroes. Once upon a time, a generation ago, there was a movie idol. The cowboy. Clean-cut, clean-shaven, the all-American super-hero—Hoot Gibson, Johnny Mack Brown and Tom Mix—rode the western plains astride trusty steeds in search of Indians and desperados. These were your father’s heroes. . . .

Today’s heroes and their steeds are something again! The drifter has replaced the cowpoke, and the motorcycle has superseded the mustang. A new, adventuresome cult has arisen—cycle buffs, and riding in with them comes a new trend in films.

Such a film is Paramount Pictures’ Little Fauss and Big Halsy, a saga of today. And let’s face it, Little Fauss and Big Halsy are not your father’s heroes.12

Unlike Easy Rider, which consciously nods to Hopper’s history with the western while inverting the tropes of that genre, Little Fauss and Big Halsy dismisses the western in its advertising slogans in an attempt to capture a youth audience unified in its disdain. Similarly, the blurb of Eastman’s published screenplay aligns the film with the burgeoning new youth film: “Filled with the raw truth of the world it depicts . . . like Easy Rider and Bonnie and Clyde, [Little Fauss and Big Halsy] will last in your mind.”13 However, the film only ever pays lip service to the notion of a generational counterculture struggle, such as when Pa Fauss complains of “monkey-faced sideburns.” The generous, protective Ma and Pa Fauss are little more than cogs in the narrative machinery who provide dramatic counterpoint to Little’s decision to flee the family home and accompany Halsy on the racing circuit; they are denied sufficient development to bring further emotional resonance to this moment of parting or to become more meaningful symbols of a broader generational conflict.

The Johnny Cash soundtrack is another potentially misguided attempt to emulate the Easy Rider commercial strategy. Cash was not exactly the selling point for youth that Jimi Hendrix and The Band had been on the Easy Rider soundtrack. By 1970 the man in black had mellowed into hosting his own television show on ABC, which showcased, among other guests, the newly country-fried Bob Dylan promoting his Nashville Skyline album, itself a divisive stylistic shift among his fan base. Dylan and Cash performed a duet on the first track of that album, while the two cowrote the song “Wanted Man,” which appears on the Little Fauss and Big Halsy soundtrack LP alongside the instrumental work of Carl Perkins.

Eastman’s screenplay ends on a poetic description of the final race: “Somewhere is Halsy, somewhere is Little, but they are lost in the crowd or they are not winners but rather among those who make no significant mark and leave no permanent trace.”14 In the film, Furie represents this retreat from didactic narrative focus with a freeze-frame that literally halts the race in its tracks, while the soundtrack continues over the top: the racers immobilized, the dramatic struggles that have concerned the film are frozen in time and rendered irrelevant across a field of transient, anonymous, undifferentiated racers. As a film without direction or drama, the cinematic grammar cancels itself out and halts in its very tracks, but unlike Two-Lane Blacktop, Little Fauss and Big Halsy is too lethargic even to burn, and simply ends at what should be its highest moment of drama.

Little Fauss and Big Halsy apparently came and went without a trace. It is difficult to locate reviews of the film, although Variety called it “uneven, sluggish” and “often pretentious” and lambasted the “lack of strong dramatic development [of] Redford’s character . . . apparent in his very first scene; it never changes.”15 In Interview magazine, Maggie Puner called it “a bad film in every respect. From its trite opening shot . . . to its trite closing freeze frame of Robert Redford absolutely nothing of importance happens.”16 Pauline Kael hated the film as a particularly cynical and opportunistic entry in the youth-cult cycle, viewing it as demonstrative only “of the crassness of confused merchandisers.”17 Susan Rice could say only that “it must have looked great on paper.”18 In sum, these reviews represent an early fatigue with the replication of the youth-cult cycle. The failure of Little Fauss and Big Halsy further suggests the risk inherent in casting Robert Redford against type. Two of his subsequent films, namely Peter Yates’s adaptation of the Donald E. Westlake caper The Hot Rock (Twentieth Century Fox, 1972) and his reunion with Downhill Racer director Michael Ritchie on the political satire The Candidate (dir. Michael Ritchie, Warner Bros., 1972), would receive a greater degree of critical acclaim. But it was not until the following year, when he reteamed with Butch Cassidy director George Roy Hill on The Sting (Universal Pictures, 1973), essentially reprising his role as the Sundance Kid, that his career path through the remainder of the decade and his ascent to the director’s chair were assured. Redford’s star persona was very much in the old-time mold, and his breakout roles were in essentially classical films that resisted the trends of the New Hollywood moment, allowing him to comfortably weather the changes in the industry in the late 1970s, ensuring the longevity of his career. Michael J. Pollard never really looked to be anything other than a character actor, and after his unlikely starring role in Little Fauss, he maintained his presence in a sporadic series of character bit parts.

As an exercise in replicating Easy Rider’s generic template, the failure of Little Fauss demonstrates that while the subversion of genre was briefly commercially sanctioned in the New Hollywood moment (at least at the level of production, if not of reception), the subversion of stardom was not. This is not to suggest that audiences would necessarily overlook other shortcomings in order to blissfully consume Redford’s performance, whether cast to type or not. But the film’s failure does suggest that neither imitation nor stardom could guarantee a winning commercial formula as industrial practices were aligning and reconfiguring in the struggle to retain the attentions of the youth audience. The case of Little Fauss and Big Halsy demonstrates that in the warm afterglow of Butch Cassidy, audiences were as yet unprepared to accept Redford as an unlikable cad. Star typology may have shifted, but the bankability of a known commodity playing to type had not, and the currency of superstar directors and on-screen talent alike remained essentially unchallenged.