9 • The French Connection

Eastwood’s Harry Callahan was not the only violent, unhinged detective to stalk the cinema screens of 1971. Two months before the release of Siegel’s film, Gene Hackman had made a seismic impression on critics and audiences alike with his portrayal of Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle in director William Friedkin’s The French Connection. There is no obvious parallel to The French Connection in the New Hollywood moment. More completely than Easy Rider or Vanishing Point, The French Connection melds cinematic spectacle with aesthetic self-consciousness. Like those two films, its attempt to simultaneously embrace and deviate from generic conventions ultimately delivers it into a space of narrative incoherence. Unlike Dirty Harry, which employed a transparently Classical Hollywood cinematic style to streamline its narrative momentum, The French Connection takes a subversive approach to style, stardom, and storytelling, resulting in a willfully ambiguous film that was acclaimed by critics.

The French Connection had a prolonged gestation before reaching screens in October 1971. The project originated in the exploits of New York detectives Eddie Egan and Sonny Grosso, whose investigation led to the interception in 1961 of the largest drug shipment ever detected on US soil, uncovering fifty kilograms of heroin imported by a cadre of French gangsters and New York mafiosi. In 1969 author Robin Moore published a written account of the case under the title The French Connection. Moore’s previous novel, The Green Berets, had been turned into a film in 1968 (dir. Ray Kellogg, John Wayne, and an uncredited Mervyn LeRoy, Warner Bros.-Seven Arts), one of the first Hollywood films to openly depict the American war in Vietnam. This jingoistic John Wayne vehicle was tonally at odds with the changing of the guard afoot in Hollywood at the time. Similarly, Moore’s French Connection is very much of the pulpy, no-frills, true-crime variety, long on procedural detail and glorification of police work and short on any attempts to humanize or render sympathetic its heroes or their investigation. None of this suggests a lineage that would beget one of the touchstone films of the New Hollywood.

William Friedkin

William Friedkin came to The French Connection having spent years alternating between populist and more serious works. Friedkin began working in the mailroom of a local television station in his native Chicago at age sixteen and graduated to directing live television two years later.1 His early television credits include an episode of The Alfred Hitchcock Hour (NBC, 1965), the Time Life: March of Time documentary newsreel series, and Pro Football: Mayhem on a Sunday Afternoon (ABC, 1965). In 1965 Friedkin moved to Los Angeles, where he directed three features: Sonny and Cher’s failed attempt at Beatles-style mania, Good Times (Columbia Pictures, 1967), which offered a similarly uneven pastiche of film genres a year before Rafelson’s Head; The Night They Raided Minsky’s (United Artists, 1968), a period burlesque musical, notable for blending documentary footage with the dramatic material in frenzied montage; and a dour adaptation of Harold Pinter’s The Birthday Party (Continental Distributing, 1968).

Friedkin’s fourth film, The Boys in the Band (1970), proved to be his breakout. Also set during a birthday party, The Boys in the Band betrays its stagey origins in its employment of a single location for the entirety of its running time. It was also one of the first American studio films to depict homosexuality in a clear-eyed, even-handed manner in a moment when this subject was still very much off-limits for Hollywood. Friedkin’s subsequent controversial flirtation with controversial depictions of homosexuality in Cruising (United Artists, 1980), along with his continual pursuit of taboo sensationalism from The Exorcist (Warner Bros., 1973), through Killer Joe (LD Entertainment, 2011), suggests that if nothing else, he is a career opportunist, if not an arch misanthrope. Nevertheless, with The Boys in the Band, and the veneer of critical respectability that accompanies theatrical film adaptations, it seemed that Friedkin’s directorial career was heading toward a well-established, middlebrow cinematic tradition. Friedkin later told Peter Biskind that he observed a widening gulf opening between the films he was directing at that time and the films he wanted to make: “I had this epiphany that what we were doing wasn’t making films to hang in the fucking Louvre. We were making films to entertain people and if they didn’t do that then they didn’t fulfil their primary purpose.”2 On the cusp of joining the ranks of the New Hollywood auteurs, Friedkin was experiencing a realignment of his relationship with cinema that contrasted starkly with the loftier artistic ambitions of the Rafelsons or Hoppers of the period.

Production History

Given the kinds of films for which he was known at that point, Friedkin seems an unlikely choice to direct the adaptation of Moore’s French Connection novel, the rights for which had been purchased by producer Phil D’Antoni.3 D’Antoni had just had a major hit with his first feature film production credit, Bullitt, and was keen to bring a similarly down-at-heel approach to his new acquisition. D’Antoni actively courted Friedkin on the strength of the director’s 1965 television documentary The People vs. Paul Crump, which offered an unapologetically gritty perspective on urban Chicago life in its reenactment of a botched robbery and shooting of a white security guard, for which the young African American Paul Crump was sentenced to death despite his protestations of innocence. D’Antoni felt that Friedkin’s sensibility was an ideal match for the producer’s new property and sent him a copy of Moore’s book, which Friedkin claims he “couldn’t read. . . . I only knew from the dust jacket what it was about.”4

Figure 9.1. William Friedkin behind the camera on The French Connection. From “Anatomy of a Chase” by William Friedkin, Take One 3, no. 6 (July–August 1971): 25. Copyright Directors Guild of America, reprinted from the official Guild magazine, Action.

Nevertheless, Friedkin flew out to New York and met the real subjects of the book, Eddie Egan and Sonny Grosso. After accompanying the detectives on actual drug busts for research purposes, Friedkin agreed to direct the film on the condition that he be allowed to oversee a significant reworking of Moore’s book during the adaptation process.5 D’Antoni commissioned several screenplays for The French Connection. Alex Jacobs, who adapted Richard Stark’s similarly procedural hard-boiled novel The Hunter (1962) for John Boorman as Point Blank (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1967), submitted the first draft. Robert E. Thompson, writer of the grim Depression-era dance-a-thon They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (dir. Sydney Pollack, Cinerama Releasing Corporation, 1969), also wrote a draft, but both were rejected by Friedkin.6 D’Antoni suggested that they might get an appropriately street-level perspective from the young writer Ernest Tidyman, who had penned the as-yet unreleased Shaft, with which D’Antoni and Friedkin were familiar by reputation. Friedkin and D’Antoni became more actively involved in Tidyman’s writing process. D’Antoni recounts that the three men “would meet every morning from nine to twelve in Billy’s apartment, and we would discuss, step by step, scene by scene, page by page [the plot of the film]. . . . Then Ernest would go off at twelve noon, write the pages, and the next morning we would meet again, read the pages, correct them, and go on to the next thing.”7

The resulting plot retained only basic elements from Moore’s factual account of the actual police investigation. Eddie “Popeye” Egan and Sonny “Cloudy” Grosso were renamed Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle and Buddy “Cloudy” Russo, respectively (thus eliminating the Cloudy pun), while villains Patsy Fuca, Jean Jehan, and Jacques Angelvin became Sal Boca, Alain Charnier, and Henri Deveraux. The basic conceit of police surveillance uncovering and ultimately breaking the conspiracy to import heroin from France to the United States concealed within an automobile remained, but much of the procedural detail of Moore’s novel was eliminated, and entire episodes of narrative were invented as Tidyman, Friedkin, and D’Antoni fictionalized Moore’s novel.

Tidyman’s screenplay was rejected by numerous studios. The project was picked up, and promptly dropped, by National General, prompting Friedkin to hurriedly complete The Boys in the Band while The French Connection was being rewritten and repackaged to shop to various studios.8 Despite D’Antoni’s recent success with Bullitt, Friedkin represented an unknown quantity as director, and mild acclaim for his last two theatrical adaptations inspired no confidence that he could capably handle the shift to directing a thriller such as French Connection, replete with elaborate action set pieces. However, Richard Zanuck at Fox was immediately drawn to the project, interested in what a director such as Friedkin would bring to the material.9 Fox continued to suffer financial troubles associated with disastrous production decisions in the previous decade, when it had invested heavily in elaborate musicals such as Doctor Dolittle (dir. Richard Fleischer, 1967) and Star! (dir. Robert Wise, 1968). Much like the deal made with Richard C. Sarafian on Vanishing Point, Zanuck offered Friedkin and D’Antoni a relatively meager budget of $1.5 million in exchange for considerable creative freedom, which the director relished.10

Casting and Characters

Casting the film proved as intensive as writing it had been. Friedkin had been impressed by Peter Boyle’s starring performance as a hippie-slaying hardhat in Joe and offered him the lead as “Popeye.” Boyle turned down the part, saying he was more interested in pursuing romantic leads.11 Television star Jackie Gleason was also considered for the role, but the studio didn’t want him, long memories stretching back to the troubled financing of his Chaplin-referencing vanity project Gigot (dir. Gene Kelly, 1962).12 The real-life Eddie Egan wanted Paul Newman or Rod Taylor to play him and Ben Gazzara to be Grosso. The studio also briefly considered casting the detectives as themselves, but it was not to be, although Egan does turn up in the film as the police chief, Walt Simonson, and Grosso has a brief cameo as a man at the airport. Furthermore, both detectives were kept on as technical advisers throughout the production.13

Unable to reach an agreement on the casting of the lead role, Zanuck insisted that he did not want a major star for the film, as his impetus of “looking for reality” dictated the role should go to a virtual unknown.14 On these grounds, Zanuck and fellow studio executive David Brown suggested Gene Hackman, who, despite his memorable supporting role in Bonnie and Clyde, had failed to make an impression beyond that of a character actor. At Zanuck and Brown’s urging, Friedkin met with Hackman, and he later claimed that their meeting put him to sleep.15 Friedkin did not like Hackman and did not think him suitable for the part. However, such was his fear that the project would dissolve if he did not tow the studio line, he cast Hackman nevertheless.16

For the next two months Friedkin, Hackman, and Roy Scheider accompanied Egan and Grosso on drug busts and arrests.17 Friedkin was obsessed with instilling in his performers the reality of police work and the narcotics trade, and he reckoned that their immersion in the daily activities of police procedure would lend authenticity to their performances. Almost immediately Hackman came into conflict with Friedkin, and the real Egan took an instant dislike to the actor. In the Making the Connection: The Untold Stories of “The French Connection” documentary, both Hackman and Grosso recall instances of friction between the actor and the police detective he was set to play from their earliest meetings in preproduction.18 Both individuals came to the project having lived very different lives, and the caustically prejudiced Egan quickly clashed with the liberal midwesterner Hackman, who was himself struggling to reconcile his antiauthoritarian personal politics with the inflammatory subject on whom he was basing his performance.

Friedkin’s directorial approach when working with actors on The French Connection is redolent of other key films of the New Hollywood moment, from Easy Rider through Two-Lane Blacktop. Shooting on location, Friedkin assembled his performers under conditions that resembled documentary reenactment as much as traditional drama and had them react to one another as the situations unfolded around them and the cameras rolled. Interviewed three years after The French Connection, Friedkin recalled his shooting methodology was “to achieve as much spontaneity as possible . . . to work with actors who are free to throw away the script. [Actors] who, like me, work on a script as hard as they need to, and then disregard it and just become the character[s].”19 Later still, Friedkin would say of the film that “I don’t think there’s a line in it, or a word, that [Ernest] Tidyman wrote.”20 The resulting performances represent a key point of departure from more traditional realizations of the policier genre, one obvious difference between The French Connection and Dirty Harry. All of the performances in The French Connection unfold with a loose, improvisatory naturalism, while Jerry Greenberg’s editing pares them back to elliptical fragments in a taut, documentary-style framework. Friedkin’s insistence on bringing a documentary rigor to his directorial style, together with Zanuck’s vision that the film would convey a central mode of realism, aligns The French Connection with the realist ambition of many New Hollywood films. In The French Connection Friedkin implements the voguish stylistic characteristics of the New Hollywood within the constraints of a clearly defined genre, at a time when recombinations of disparate generic forms (M*A*S*H, Little Big Man), and the pairing of genre iconography with the resolute abandonment of generic convention (Two-Lane Blacktop) were prevailing production trends. The French Connection subverts generic convention in more subtle and subversive ways. Its subject matter and pseudo-documentary stylistic mode lull its audience into the assumption that it will follow the narrative conventions of the policier. Hackman’s performance offers one jarring point of generic discontinuity, and the film eventually departs wholly from a generically enshrined narrative, even as the formal narrative superstructure continues to progress along generic lines. In other words, the film’s formal and narrative systems lead the audience to expect that Popeye will eventually catch the crooks, even as they ultimately escape out from under his nose.

Hackman/Eastwood

The French Connection was Hackman’s first major lead role. Ostensibly, Hackman’s casting fulfilled Zanuck’s directive that The French Connection have no stars. Despite his Academy Award nomination for his intense performance as Buck Barrow in Bonnie and Clyde, Hackman had failed to consolidate that success with a breakout performance in the ensuing years. He followed up Bonnie and Clyde with two attempts at capitalizing on the youth-cult phenomenon: John Frankenheimer’s The Gypsy Moths (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1969), which transplanted self-imposed alienation from the highway to the skies among a fraternity of skydivers; and Michael Ritchie’s debut Downhill Racer (Paramount Pictures, 1969), in which Hackman played Robert Redford’s skiing coach. Neither film enjoyed enormous success. Other Hackman films of the period failed to attract much attention. Largely forgotten now are films such as director John Sturges’s space drama Marooned (Columbia Pictures, 1969), with Gregory Peck; the violent prison drama Riot (dir. Buzz Kulik, Paramount Pictures, 1969); and the low-key theatrical adaptation I Never Sang for My Father (dir. Gilbert Cates, Columbia Pictures, 1970), a film with some thematic parallels to Five Easy Pieces, and in which Hackman’s Gene Garrison attempts to care for his aging father, played by Melvyn Douglas.21

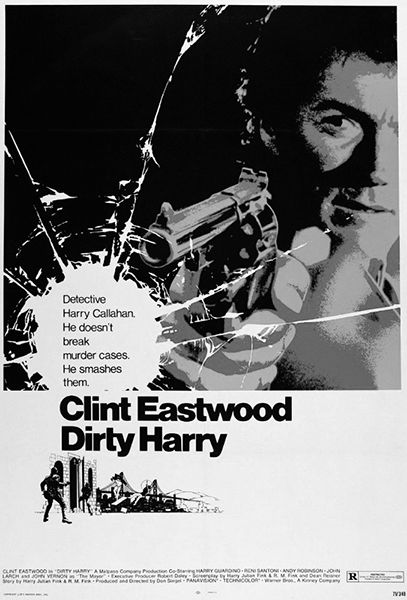

Where Hackman registered in the public consciousness, it was as a semiobscure bit player on the fringes of the New Hollywood, similar to Friedkin’s status in the wake of the limited success of The Birthday Party and The Boys in the Band. Given his relative unfamiliarity, Hackman represented an unknown quantity for audiences in 1971 and provided no comfortable star persona or generic affiliation around which audiences could form their preconceptions. The same could be said of director Friedkin. This contrasts markedly with Dirty Harry and the inescapable presence of Clint Eastwood, which looms large over the film long before the first reel has even been projected. For Eastwood, Dirty Harry represented a conscious attempt to separate his on-screen persona from its association with the western genre. Nevertheless, Dirty Harry essentially finds Eastwood’s “Man with No Name” character transplanted into a contemporary San Francisco setting, governed by an equally rigorous set of generic conventions. Much of the appeal of Dirty Harry comes from witnessing Eastwood’s fulfilment of his unspoken contract with the audience, as he relentlessly pursues the psychopathic Scorpio through a gradually tightening series of action set pieces and narrative obstacles. Harry’s dirtiness is carefully sanctioned by the screenplay, as is the satisfaction we derive from watching it: Scorpio is so cartoonishly evil that the film must conclude with his elimination, despite the interventions of the one-dimensional, spineless mayor. These tangential, undeveloped characters exist as gears in the narrative machinery to wind up the tension as they periodically appear to defer Harry Callahan from achieving his goal: killing Scorpio. Once this goal has been accomplished, the film may end. Over all of this hangs the specter of Clint Eastwood, a signpost for a particular kind of generic entertainment. Harry Callahan is inescapably Eastwood, and Dirty Harry is inescapably generic. Once Scorpio lies dead, the generic contract is fulfilled.

Eastwood’s Harry Callahan is defined by a cool, unhurried machismo. Even when he is pursuing criminal adversaries, Dirty Harry affords its star time to deliver poker-faced wisecracks before discharging the killer shot. These signature mannerisms are a part of Clint Eastwood’s established on-screen persona. “Dirty” Harry Callahan is sympathetic to the extent that by entering the cinema, the viewer enters a contract that she or he will spend the following one hundred minutes watching Clint Eastwood blow people away. Siegel and Eastwood are good enough to uphold their end of the bargain.

The relationship between stardom and generic satisfaction in The French Connection is far more complex. Hackman came to the project free of the lineage of cinematic associations that Eastwood brought to Dirty Harry. Eastwood’s well-established screen persona provided all of the backstory and psychological motivation an audience needed to follow Dirty Harry. Hackman’s Popeye Doyle is something of a total reversal of Eastwood’s Callahan. Where Callahan enters his film striding purposefully onto the rooftop crime scene, Popeye literally crashes into The French Connection absurdly dressed as Santa Claus (his first line in the movie, delivered in character as Santa while on an undercover stakeout, is “Merry Christmas,” after which he leads a cadre of children in an impromptu rendition of “Jingle Bells”), in a breakneck foot chase through Harlem. The speed of this action sequence is emphasized through a series of shots taken from a moving vehicle racing alongside the subject on the sidewalk and cut at a rapid pace. The film does nothing to shy away from the brutality with which Popeye and Cloudy manhandle the African American suspect, punching and kicking him while he is on the ground, dragging him handcuffed to a vacant block, where Cloudy menaces him with a metal pipe, and Popeye interrogates him with a series of seeming non sequiturs (“When’s the last time you picked your feet? Who’s your connection, Willie? . . . Is it Joe the barber? . . . You ever been to Poughkeepsie?”). This image of heavy-handed authoritarian violence, from a white cop to a black suspect, is a long way from the empowerment proffered in Shaft. The long take frames Popeye, Cloudy, and the suspect on the debris-strewn block, as Hackman wags his finger wildly, gestures forcefully, and yells uncontrollably (“I want to bust him!”) as the Santa Claus beard dangles from his neck.

Popeye’s entrance into the film establishes several recurring motifs: Doyle’s aggressive, physical presence; the unexpected moments of physical action that will periodically intrude into the film; and the fundamental incoherence of the plot. Along with Popeye’s absurd Santa costume, his dialogue about “picking your feet in Poughkeepsie” serves no clear narrative purpose here, and its meaning is never explained. Although it was derived from a catchphrase of the real Egan, this fact is never made clear in the film.22 In this sequence, it functions as nothing more than an illogical utterance that adds color to Hackman’s portrayal of the character.

Hackman maintains this pattern of aggression (both physical and verbal), barely contained physical activity, and outbursts throughout The French Connection. Todd Berliner observes that Hackman “instills the character with a gruff, abrasive energy: drumming his fingers, banging on tables and cars, smacking his chewing gum even as he’s drinking, rubbing his face, chomping food, running his tongue along the inside of his bottom lip. The actor never stays still.”23 In contrast to Eastwood’s performance in Dirty Harry, which trades almost entirely on the singular, cultivated mannerisms of a well-established screen persona in the Old Hollywood mold of stardom, Hackman’s Popeye represents the actor’s wholesale transformation into his interpretation of Egan: nervy, compulsive, all impulsive hunch. Where Harry seethes cold, Popeye explodes hot. Hackman’s total immersion in the role is very much in the New Hollywood method mold of Al Pacino, Nicholson, and Hoffman. His eventual triumph at the Academy Awards for 1971 perhaps set the precedent for Hollywood’s acknowledgment of the actor’s ability to physically and psychologically become a monster, a feat Robert De Niro would sensationally repeat in Raging Bull (dir. Martin Scorsese, United Artists, 1980).

These differing modes of stardom in Dirty Harry and The French Connection are established with the trailers for each film. The trailer for Dirty Harry places Eastwood front and center, with the actor’s name appearing on-screen twice, bookending the trailer. Furthermore, the voiceover narrator conflates Eastwood with the Dirty Harry character, at one point stating, “Clint Eastwood: detective Harry Callahan. You don’t assign him to murder cases. You just turn him loose.” The prime impetus of the Dirty Harry trailer is branding the film as consistent with the style of violent entertainment associated with Eastwood’s previous roles, albeit transplanted from the Wild West into a contemporary urban setting.

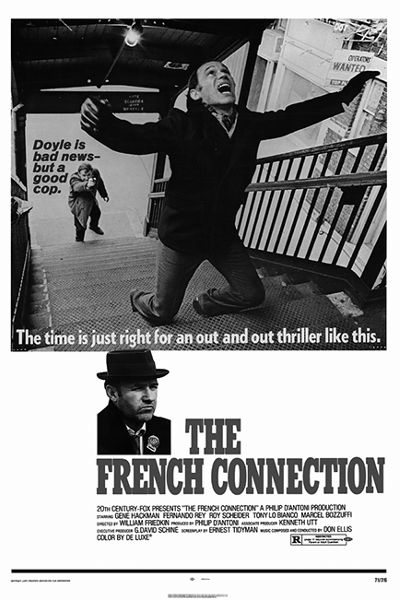

Figures 9.2 and 9.3. Where Eastwood shares equal billing with the film’s title on Dirty Harry’s poster, Hackman’s name does not appear prominently on The French Connection’s poster. Nonetheless, “the time is just right for an out and out thriller like this.”

The trailer for The French Connection emphasizes Popeye Doyle, from its opening line of dialogue, “alright, Popeye’s here,” to its voiceover narration, which states: “Doyle fights dirty, and plays rough. Doyle is bad news. But he’s a good cop.” Gene Hackman is mentioned only once by name in the trailer, whereas Popeye Doyle is mentioned six times. Each trailer employs the stylistic traits of the film it promotes: the Dirty Harry trailer contains 75 cuts and clips from 10 different sequences of the film in its 3:25 running time, whereas The French Connection trailer contains 115 cuts and clips from 18 different sequences in its significantly shorter 2:46 running time. Each film’s differing industrial scale is also evident in its respective aspect ratio: The French Connection’s gritty, street-level photography is framed in industry-standard 1.85 : 1, whereas Dirty Harry is shot in 2.35 : 1 Panavision, reflecting Eastwood’s outsized star persona.

It is worth considering both films’ status as “genre films,” which is defined by Thomas Schatz as revolving around, “familiar, essentially one-dimensional characters acting out a predictable story pattern within a familiar setting.”24 In opposition to the genre film, Schatz also defines the nongenre film, which “tended to attract greater critical attention during the studio era” and which is defined by a plot that, “does not progress through conventional conflicts toward a predictable resolution.”25 Although Schatz was writing here about the Classical Hollywood era, which he believes ended around 1960, Dirty Harry nonetheless falls fairly neatly into the category of a genre film. While The French Connection purports to be a genre film, it in fact employs the narrative characteristics of the nongenre film.

With none of the genre affiliations of Eastwood’s Dirty Harry, The French Connection lacks clear signposts for how an audience should respond to its protagonist. Harry Callahan’s litany of prejudices is delivered with a heavy dose of knowing irony by a charismatic actor already considered likable by a sizable segment of the moviegoing public. It is difficult to imagine that even the most ardent Gene Hackman fan would not feel discomforted by the sight of Popeye aggressively and demeaningly ordering African American bar clientele up against a wall. Indeed, ambivalence toward the unpleasant aspects of Popeye Doyle’s character plagued Hackman on set. Friedkin was already offside over his compromise with Fox to cast Hackman in the lead and felt convinced that the actor “was never prepared to commit one hundred percent as the kind of racist . . . cop.”26 Hackman later recalled that he “talked to . . . [Friedkin] about some of the racist dialogue, and . . . he wouldn’t hear of it, he said, ‘that’s the way it is, and that’s what we have to do,’ so I just had to kind of suck it up and do the dialogue.”27 Furthermore, the real Eddie Egan, on-set in his advisory capacity, balked at what he perceived as the actor’s unwillingness to “play everything one hundred percent mean.”28 Roy Scheider recalls Hackman’s struggle to humanize Popeye and Friedkin’s resistance: “Gene kept trying to find a way to make the guy human, to give the guy three dimensions . . . and Billy kept saying ‘no, he’s a son of a bitch, he’s no good, he’s a prick.’”29 The resulting battle of wills perhaps contributed to the atmosphere of provocation and antagonism in Hackman’s edgy performance and in the film as a whole. Friedkin retrospectively attributes Hackman’s performance to his own directorial efforts to “light a fire under . . . [Hackman] every day . . . hour by hour, and make him crazy.”30 Ultimately, the confrontational aspects of Popeye Doyle’s personality, combined with Hackman’s committed performance and the lack of a clarifying star persona, generate confusion about whether or not the protagonist of The French Connection is as morally repugnant as he appears to be. The film never articulates its moral stance on its subject, but it is interesting to note that Popeye Doyle’s relentless belittling and disempowerment of African Americans not only coincides with the arrival of blaxploitation, but officially emanated from Shaft scribe Tidyman—however, all reports suggest that these elements were largely inventions of Friedkin.

Like Dirty Harry, we see little of Popeye Doyle’s life outside of his police work. Like Harry Callahan, Doyle is such a resolute, authoritarian bully it is difficult to imagine him functioning in any other profession. The rare glimpses of Popeye’s personal life—hanging out in bars and his unbelievably effortless seduction of a much younger woman—do little to dispel the unpleasant aspects of his character. Like many of the American films of its era, The French Connection limits its roles for female characters to wives, girlfriends, and often-unspeaking objects of sexual desire. Could it be that the supposedly conservative, fascist Dirty Harry offers a more sympathetic portrayal of its female characters? See Harry’s dialogue with Chico’s wife at the hospital. While this film still casts women as wives and damsels in distress to be protected (Ann Mary Deacon), Chico’s wife Norma (Lyn Edgington) is at least permitted the agency to hold a thoughtful conversation with Callahan, better than anything afforded to the anonymous, unspeaking sex object who shares Popeye Doyle’s bed for no other reason, seemingly, than to affirm his heterosexuality for the audience. Popeye’s list of transgressions doesn’t stop at his racism and womanizing; throughout the course of the film, he flagrantly abuses and assaults criminal suspects, inadvertently allows several suspects to escape, and causes wanton property damage during a car chase, which climaxes when Popeye shoots his fleeing, unarmed suspect in the back.

The New York City of The French Connection is a cesspool of crime, corruption, and decay. In a decade that offered few flattering portrayals of America’s urban centers, the stygian hell of Friedkin’s film joins Scorsese’s Taxi Driver as one of the most unremittingly bleak. Friedkin’s catalog of locations (dingy bars, shabby diners, frozen, trash-strewn streets) provides a fittingly decrepit backdrop for Popeye Doyle’s obsessive pursuit of the drug dealers. In this environment, it is difficult to imagine that his heavy-handed bullishness will effect any meaningful change; the removal of these particular drug dealers from the scene will change little for those awash in the sea of crime, addiction, poverty, and sickness. Popeye can perhaps be understood as a product of his environment, his routine antagonisms an automatic response to the violent world around him. The detective work of The French Connection offers no centering balance to its unstable moral universe, and at the end of the film the most senior figures in the drug smuggling ring all escape. By contrast, Dirty Harry’s San Francisco is as outlandish as Siegel’s New York in Coogan’s Bluff, a conservative’s paranoid playground of liberal permissiveness gone mad, in which African American bank robbers and psychopathic snipers walk the streets, and gay men solicit sex in parks at night, all with the blessing of City Hall. Scorpio, impossibly evil, is an aberration that must be expunged to restore some balance to the moral universe of the film. Regardless of whether or not we find Harry’s actions morally objectionable, he is the only man prepared to take the steps to eliminate the menace. The adversaries of The French Connection are of a different mold: shadowy, affluent, with motivations and intentions that may only be guessed at as fragments of information come to light, suggesting a vast conspiracy that stretches beyond the confines of the diegesis. Friedkin’s filth-ridden New York hints at the seedier underbelly of Dirty Harry’s sunny San Francisco. Popeye is firmly enmeshed in the belly of a different beast, a perpetual struggle for daily survival via base physical dominance.

Style

The formal style and narrative mode of The French Connection are unconventional, to say the least. Zanuck’s insistence that the film convey a fundamental sense of realism is reflected through the documentary-style aesthetic Friedkin pursues: handheld camera and rapid cutting influenced by Cota-Gavras’s Z (Cinema V, 1969); fast film stock; overlapping and indistinct audio; a fragmentation of cinematic time and space, with montage sequences often arranged by association, rather than through spatially motivated means; naturalistic, seemingly off-the-cuff performances; and real-world locations. These elements convey a sense of immediacy that is lacking from the more stylistically conventional Dirty Harry, despite its similar emphasis on location shooting. Siegel frames Dirty Harry largely in wide shots, with the camera panning to follow the characters’ movements through space, breaking into shot/reverse shot editing to emphasize important lines of dialogue, whereas Friedkin is concerned with a perpetual sense of cinematic motion, with his constantly moving, often handheld shots cut together at a rapid pace, emphasizing montage over long takes or spatial coherence, and the jarring nature of editor Greenberg’s rapid cutting drawing attention to the cinematic form and auteurist intention.

Less apparent, but equally indicative of the position The French Connection holds amid the films of the New Hollywood, is its continual recourse to narrative failure. According to Todd Berliner, The French Connection works “by employing and then subverting conventional Hollywood scenarios . . . creat[ing] unsettling narrative ambiguities,” in the form of incoherence and genre deviation.31 A confrontation between Doyle and his superiors takes place beside a gruesome, narratively unmotivated car wreck; a sniper, aiming to silence Doyle, misses his target and instead hits a woman pushing a pram; as previously noted, the celebrated car chase ends with Popeye shooting a fleeing unarmed man in the back; and the film concludes with Popeye Doyle bungling the final sting, allowing the principal suspects to escape and inadvertently killing the FBI agent Mulderig in the process.32 All of these sequences are the inventions of Friedkin and Tidyman; none appears in Moore’s original book or the factual case on which it was based. By emphasizing such unconventional elements of his film and inserting deliberately incongruous moments that are extraneous to the original source material, Friedkin casts The French Connection alongside many of the post–Easy Rider films. Despite its urban police setting and superficial genre affiliations, the pall of failure, alienation, and death hangs over its conclusion. A series of titles at the end of the film reveal that for all his bluster, Popeye has been unable to affect any real change: the big fish of The French Connection all slip through the net, and the film ends with its characters in a kind of generic stasis amid a disquieting atmosphere of failure and defeat. This descending mood of inaction and fatalism repeats across the conclusions of many post–Easy Rider youth films. Like Easy Rider, after depicting a morally questionable protagonist, The French Connection must end with his punishment, not his triumph. Friedkin’s use of the documentary aesthetic, or as he referred to it, “induced documentary . . . [making] it look like the camera just happened on the scene,” imbues each moment of the film with a sense of visceral realism, which combines with its rapid pace to gloss over its plot holes and narrative incoherencies.33 These fashionable conventions meant that the film was viewed under the critically approved auspices of the nascent New Hollywood, ensuring its eventual triumph at the 1971 Academy Awards. Crucially, The French Connection also trumped Dirty Harry at the box office; Friedkin’s film was the third-highest-grossing release of the year, while Dirty Harry came in at number six.34

Reception

Critical responses to The French Connection generally praised Friedkin’s overwhelming cinematic style, and his achievements were confirmed by the industry itself when the film won five Academy Awards the following year. Pauline Kael, the self-styled moral arbitrator of mainstream film criticism at the time, expressed some reservations about the warts-and-all presentation of Popeye Doyle, casting his lack of “any attractive qualities” as “right-wing, left-wing, take-your-choice cynicism . . . [and] total commercial opportunism passing itself off as an Existential view.”35 Elsewhere in her review, however, Kael praises the film as “an extraordinarily well-made new thriller”36 of “almost unbearable suspense”37 and “sheer pounding abrasiveness.”38

Kael was less equivocal in her assessment of Dirty Harry and generally mirrored the wider reception that greeted the film, which she lambasted as “a remarkably single-minded attack on liberal values, with each prejudicial detail in place,”39 and “a deeply immoral movie.”40 When comparing the two films in her Dirty Harry review, Kael wrote that Siegel’s film “is not one of those ambivalent, you-can-read-it-either-way jobs like The French Connection; Inspector Harry Callahan is not a Popeye—porkpie-hatted and lewd and boorish. He’s soft-spoken Clint Eastwood—six feet four of lean, tough saint, blue-eyed and shaggy-haired. . . . He’s the best there is.”41 Kael’s inference here is clear: Dirty Harry, with its identifiable, charismatic star and adherence to old-fashioned generic structures, belongs to the out-of-favor mode of Hollywood past, and Siegel’s invisible, Classical Hollywood directorial style leaves its problematic political content in clear sight. On the other hand, the bravura pseudo-documentary style of The French Connection and Hackman’s mesmerizing performance assert themselves as objects worthy of critical praise, not only obscuring the film’s no less problematic content, but, on the contrary, shifting the context of critical reception so that Popeye’s racism, for example, may be regarded as unflinching realism rather than underlying bigotry.

Ultimately, The French Connection employed the prerequisite devices to be considered a part of the New Hollywood: contemporary resonance; genre frustration and revisionism; an emphasis on performance over stardom; a downbeat, fatalistic ending; and a self-conscious foregrounding of film style. Such characteristics signaled to the critical establishment that The French Connection was a candidate for canonical elevation in the burgeoning New Hollywood moment, whereas Dirty Harry belonged to the receding Hollywood of old. Such categorizations have continued to inform recent approaches to each film: Paul Ramaeker’s 2010 “Realism, Revisionism and Visual Style: The French Connection and the New Hollywood Policier” considers the stylistic influence of Friedkin’s film on a post-Classical action aesthetic, whereas Joe Street’s “Dirty Harry’s San Francisco” considers the political ramifications of that film’s setting.42 The fate of these two films demonstrates that in the critically constructed New Hollywood, conservatism resided not in political outlook, but in the mechanics of film style, the politics of Hollywood’s star system and in the interpretations of critics with political agendas of their own. In both cases, political readings were colored by form and extratextual elements, not content alone. Closer analysis of The French Connection reveals its difficult hybrid status. Friedkin’s uneasy standing, aligned with neither Old nor New Hollywood, was confirmed by the unprecedented commercial success of his subsequent film The Exorcist, which was in its own way an important sociocultural precursor to Jaws as a major “event film” blockbuster of the 1970s. Friedkin’s big splash in the first half of the decade would not ensure career longevity; like fellow transitional figure Michael Cimino, Friedkin’s slide from feted superstar to persona non grata would neatly coincide with the decade’s end, but Oscar’s stamp of approval on The French Connection has ensured the longevity of that particular film.