Chapter 4

Whose Perfect Right?

Between people, as among nations, respect of each other’s rights insures the peace.

— Benito Juárez

In an interview for his 2006 book Therapy’s Best, therapist-author Howard Rosenthal asked Your Perfect Right coauthor Bob Alberti this question: “Are people more assertive now than when you first published the original [1970] edition?” Bob’s response offers a kickoff for this chapter’s discussion of how we treat one another in an assertive society:

It seems that we have — as a society — reached a point of much greater openness and freedom of expression. That may not be all to the good. … Some folks have used “assertiveness” as a pretext for all sorts of uncivil behavior — misinterpreting the concept as if it gave them license for rudeness, road rage, and boorishness. Fortunately, that’s not the rule, but I sometimes think we may have “created a monster,” despite our best efforts to teach a self-expressive style that is respectful of others.

Up to now, you’ve been exploring what it might mean to you to become more effective in expressing yourself. Now let’s take a look at some of the ways assertive actions fit — or don’t fit — into a larger view of society.

We believe and have long taught the concept that every individual has the same fundamental human rights as every other, regardless of gender, age, ethnicity, role, or title. That’s an idea worth some thought. And if the notion of equality of human rights is not idealistic enough for you, here’s another: equality is fundamental to assertive living. We’d like to see all people exercise their rights without infringing on the rights of others.

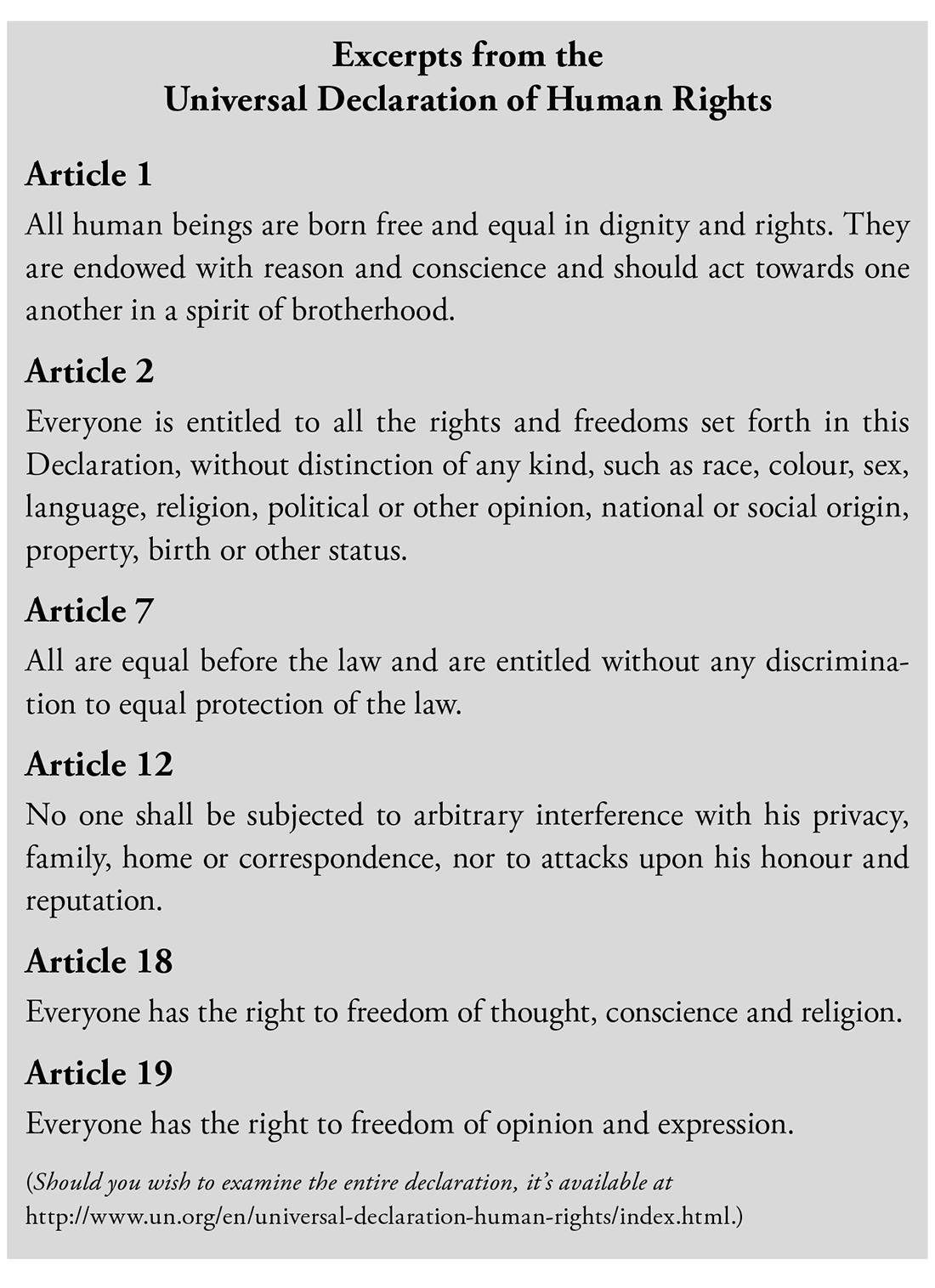

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948, is an excellent statement of goals for human relationships. The excerpt on the next page presents a few key clauses from that document.

The declaration is idealistic, to be sure, and we doubt that any country in the world actually lives up to its ideals. Still, we urge you to let those principles encourage you to support the rights of every individual — including yourself!

Keeping a broad view of individual human rights can help us to counteract the forces that pit us against one another. We are all human beings after all, citizens of a very small planet, and dependent upon each other in many ways. We need mutual support and understanding for our very survival.

Are Some More Equal Than Others?

Unfortunately, society often evaluates human beings on scales that rank some people as more important than others. Here are a few popular notions about the value of people. Which ones do you agree with?

The lists could go on and on. Many of our social and political organizations tend to perpetuate these myths and allow individuals in “less valuable” roles to be treated as if they were of lesser value as human beings. The good news, however, is that lots of folks are finding ways to express themselves as equals.

Assertive Women in the Twenty-First Century

Through the first few editions of this book, the movement popularly known as “women’s liberation” was gaining momentum. We don’t hear the term much anymore, but the concept of liberated individuals — free to be themselves — has not gone away.

An assertive, independent, and self-expressive woman is capable of choosing her own lifestyle, free of dictates of tradition, government, husband, children, social groups, and bosses. She may elect to be a homemaker and not fear intimidation by those who work outside the home. Or she may elect to pursue a male-dominated profession and enjoy confidence in her rights and abilities.

In their excellent book The Assertive Woman, Stanlee Phelps and Nancy Austin present the behavioral styles of four “women we all know.” Their characterizations of “Doris Doormat,” “Agatha Aggressive,” “Iris Indirect,” and “April Assertive” are self-explanatory by the names alone. Yet, in describing the patterns of each, Phelps and Austin help us to gain a clearer picture of the social mores that have in the past devalued assertiveness in women. Agatha gets her way, though she hasn’t many friends. Iris, the sly one, also gains most of what she wants, and sometimes her “victims” never even know it. Doris, although denied her own wishes much of the time, was once highly praised by men and by the power structure as “a good woman.” April’s honesty and forthrightness may have created trouble for her at home, at school, on the job, and even with other women.

In her sexual relationships, an assertive woman can be comfortable taking initiative and asking for what she wants (and thereby freeing her partner from the expected role of making the first move). She and her partner can share equally in the expression of intimacy.

She can say no with firmness — and can make it stick — to requests for favors, to unwanted sexual advances, to her family’s expectations that she “do it all.”

As a consumer, she can make the marketplace respond to her needs by refusing to accept shoddy merchandise, service, or marketing techniques.

A number of factors have combined to help women achieve long-overdue gains that acknowledge their individual rights. The popularity of assertiveness training for women, including specialized workshops in management and other fields, has been a contributing factor. Women of all social viewpoints, ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds, and educational and professional involvements — homemakers, hard hats, and high-ranking executives — have made phenomenal gains in assertive expression. As a result, the old “ideal,” which identified women as “passive, sweet, and submissive,” is no more.

Today’s assertive woman is an assertive person who exhibits the qualities we espouse throughout this book; and she likes herself — and is liked — better for it!

What’s more, many of these changes are recognized around the world. This book and The Assertive Woman have been translated and published in China, Germany, India, Israel, Japan, Poland, and many other countries. According to press reports, although women continue to be subject to severe cultural and legal restrictions, even in some conservative Muslim societies women are making gains in personal and political equality.

Men Can Be Assertive Too!

We’ve enjoyed inviting audiences to imagine the following scene: John’s day has been exhausting; he has washed windows, mopped floors, completed three loads of wash, and continually picked up and cleaned up after the children. He is now working hurriedly in the kitchen preparing dinner. The children are running in and out of the house, banging the door, screaming, and throwing toys.

In the midst of this chaos, Mary arrives home from an equally trying day at her office. She offers a cursory “I’m home!” as she passes the kitchen on her way to the family room. Dropping her briefcase and kicking off her shoes, she flops in her favorite chair in front of the television set, calling out, “John, bring me a beer! I’ve had a helluva day!”

This scene is humorous partly because it counters cultural stereotypes. After all, shouldn’t John also have a career, working for a salary instead of at home? Isn’t it a man’s place to go out and conquer the world on behalf of his family? To demonstrate his manhood, his machismo, his strength, and his courage?

For too long, our society accepted as proper the stereotype of the male as the “mighty hunter” who must protect and provide for his family. Indeed, from earliest childhood, the accepted male roles of earlier days encouraged assertive — and often aggressive — behavior in pursuit of this “ideal.” Competitiveness, achievement, and striving to be the best were integral components of male child-rearing and formal schooling — much more so than for daughters. Men have been treated as if they were by nature strong, active, decisive, dominant, cool, and rational.

Late in the twentieth century, a growing number of men began to acknowledge a great gap in their preparation for interpersonal relationships. Limited in the past to only two options — the powerful, dominating aggressor or the wimp with sand in his face — most found neither to be particularly satisfying. Assertiveness offered them an effective alternative, and a new generation of men has rejected the aggressive, climbing, “success” stereotype in favor of a more balanced role and lifestyle.

Psychological and cultural concepts of “masculinity” have changed to acknowledge the caring, nurturing side of men as well. Men have recognized that they can accomplish their own life goals in assertive — not aggressive — ways. Professional advancement is available for the competent, confident, assertive man.

We have witnessed remarkable changes in our society’s definition of what it means to be a man. The emerging definition looks remarkably like the assertive man we have been encouraging for decades: firm but not pushy, self-confident but not arrogant, self-assertive but committed to equality in relationships, open and direct but not dominant.

We admire those men who acknowledge to themselves and to one another (and to the women in their lives) their needs and desires, their strengths and their vulnerabilities, their anxieties and their guilt, and the internal and external pressures that drive their lives.

Assertive men these days are held in high esteem in relationships with the important others in their lives. Family and friends are closer to and have greater respect for the man who is comfortable enough with himself that he needn’t put others down in order to put himself up. The honesty of assertiveness is an incalculable asset in close personal relationships, and assertive men are coming to value such closeness right along with the traditional rewards of economic success.

Researchers who have studied large groups of men over long time periods have noted that many men who lived the aggressive style in their twenties and thirties found that the achievements thus gained meant little in their later years. The values of personal intimacy, family closeness, and trusted friendships — all fostered by assertiveness, openness, and honesty — are the lasting and important ones.

Living in a Multicultural, Pluralistic World

The essence of our approach to assertiveness training has always been equality. The goal of this book is to foster better communication between equals, not to help one to be superior to another or to step on others to get her way. Open and honest communication — mutual, cooperative, affirming — is the process that can achieve the desired outcome of equality: a place for everyone.

These days, however, that goal may be more challenging than ever before, as the world grows smaller. Globally, economic, political, and personal changes have led to more awareness of and direct contact with people of different cultural backgrounds. Every day, right here at home, most of us can see that the world is becoming a multicultural “mixing pot” to a greater degree than ever before. It’s exciting and refreshing to see different faces, hear different languages, and encounter different lifestyles.

At times, it can also be uncomfortable.

At the time of this writing, fear of those very differences is widespread. Terrorism appears to be an ever-present threat, although its tragic results affect many fewer people than “everyday” homicides in the United States. Tensions are high around the globe as dictators and despots in nations large and small jockey for position in the struggle for international power and influence. Extremists of every stripe exploit the latest technologies in pursuit of their zeal to disrupt the peace and sway the masses. And our politicians unfortunately play on those fears, knowing such a strategy will buy them votes.

Although change far outpaces our ability to keep track, no other nation today has the cultural diversity of the United States. California is in the forefront of the interface of cultures but is by no means alone. In fact, more than half the populations of California, Hawaii, New Mexico, and Texas are people of color, including Hispanic/Latino, African American, Asian, Native American, and other ethnic groups. In the public schools — a microcosm of the larger society — teachers of English as a second language face a sea of faces from dozens of diverse cultures. In one Los Angeles school, a reported twenty-two different languages are spoken!

As California’s multiethnic population has grown, similar population changes are occurring throughout the United States.

Can we all live together? Do we respect and value one another? Or are we threatened by the entry of each newcomer, each “foreigner,” each person who is “different,” each believer in a different god?

Protection of human rights, equality of treatment, and respect for individuals regardless of ethnic or personal traits: the more we can become aware of and understand and accept one another — including those who are “different” — the stronger we will be as individuals (and as a nation and world).

How Different Is “Different”?

When people think about other cultures, they commonly assume that “all people from a culture behave in the same way.” UCLA professor Steven Lopez told us a few years ago that, for too long, “understanding” people of other backgrounds has meant lumping cultural groups together and ignoring individuals. Such stereotyping creates barriers, it doesn’t erase them.

We hear stereotypes about other cultures all the time. Here are a few: in some cultures, if a woman smiles at a stranger, it has sexual implications; African American males do not like to maintain eye contact in conversations; the male rules the household in the Mexican American culture; Saudi Arabians stand very close and seldom use their right hand when communicating; in some cultures, the death of a loved one is a joyous occasion.

Can it be that all people from a certain culture (or all women, or all teenagers) have the same beliefs? Or act the same way? Of course not. And such stereotypic assumptions are as dangerous as they are false. We get into trouble when we assume that all people from any group behave in the same way or share the same beliefs.

The catch is that it’s equally false — and dangerous — to assume that “people are people” and deep down we’re all alike as human beings, regardless of our groups. Culture, gender, and age are important, and to understand an individual requires that you acknowledge these vital characteristics — and treat her or him individually.

What Does Background Have to Do with Assertiveness?

As you begin to develop assertive skills, how can you use them in dealing with people from different backgrounds?

First, treat each person with respect; second, educate yourself about the backgrounds of people you encounter; and third, if something seems unusual in an individual’s style — standing too close, avoiding eye contact, being overly shy or pushy — check it out. You might say something such as, “I find it a little uncomfortable when you stand so close to me. I guess I’m not used to that.”

Keep in mind that each human being is unique, a complex blend of age, gender, genes, culture, beliefs, and personal life experiences. All Italians, or Irish, or Vietnamese, or Mexicans are not alike, but members of each group have much in common. All teenagers, or senior citizens, or preschoolers are not the same, but it helps to know something about the needs and characteristics of a person’s group as you deal with that individual. All working women, or midlife men, or thirty-somethings are not identical, but they have similarities that may be important to be aware of if you want to get to know someone who fits one of those labels.

In sum, as you seek to understand people of other cultures or backgrounds, begin first with the individual. Don’t underestimate cultural or group-specific behavior or overestimate the universality of human behavior. When in doubt, show respect, ask questions, and listen, listen, listen.

Society Often Discourages Assertiveness

Despite important improvements in some areas, society’s rewards for appropriate assertive behavior are not universal. The assertions of each individual, the right of self-expression without fear or guilt, the right to a dissenting opinion, and the unique contribution of each person all need greater recognition. We can’t overemphasize the importance of the difference between appropriate assertion and the destructive aggression with which it is often confused.

Assertion is often actively discouraged in subtle — or not so subtle — ways in the family, at school, at work, in faith-based communities, in political institutions, and elsewhere.

In the family, the child who decides to speak up for his or her rights is often promptly censored: “Don’t talk to your mother (father) that way!” “Children are to be seen, not heard.” “Don’t be disrespectful!” “Never let me hear you talk like that again!” Obviously, these common parental commands are not conducive to a child’s assertion of self!

At school, teachers are frequently inhibitors of assertion. Quiet, well-behaved children who do not question authority are rewarded, whereas those who “buck the system” in some way are dealt with firmly. Educators acknowledge that the child’s natural spontaneity in learning is, by the fourth or fifth grade, replaced by conformity to the school’s approach.

The results of such upbringing affect functioning on the job, and the workplace itself often is no help. At work, employees usually assume that it’s best not to do or say anything that will rock the boat. The boss is in charge, and everyone else is expected to “go along” — even if they consider the expectations completely inappropriate. Early work experiences teach us that those who speak up are not likely to obtain raises or recognition and may even lose their jobs. You quickly learn not to make waves, to keep things running smoothly, to have few ideas of your own, and to be careful how you act lest it get back to the boss.

We all have the right to express ourselves and our needs, and to feel good (not powerless or guilty) about doing so, as long as we do not hurt others in the process.

Fortunately, things have changed somewhat in recent years, with more employee rights and a greater balance emerging. A collegial atmosphere now pervades high-tech firms. Low unemployment has required employers to accommodate a variety of individuals with talent. Many people work at home, as independent contractors or telecommuters, for virtually all of their working lives. In many work environments, employees no longer fear speaking out on the job, but “whistle-blowers” — those who openly report unfair, unethical, or illegal activities in the workplace — are often shunned and rebuked, in spite of laws allegedly protecting them. There are still many influences that suggest it’s best to be nonassertive at work!

The teachings of many religious organizations suggest that assertive behavior is somehow at odds with the principles of one’s faith. Such qualities as humility, self-denial, and self-sacrifice may be encouraged to the exclusion of standing up for oneself. There is a mistaken notion that religious ideals must, in some mystical way, be incompatible with feeling good about oneself and with being calm and confident in relationships with others. Quite the contrary; assertiveness is not only compatible with the teachings of major religions, it frees you of self-defeating behavior, allowing you to be of greater service to others as well as to yourself.

Political institutions may not be as likely as the home, school, or workplace to influence the early development of assertive behavior, but political decision making still remains largely inaccessible to the average citizen. Nevertheless, it is still true that the “squeaky wheel gets the grease,” and when individuals — especially when they get together in groups — become expressive enough, governments usually respond. Of course, since September 11, 2001, restrictions on civil liberties (such as the USA PATRIOT Act) have made it more hazardous for individuals — and even groups — to express dissent from government policies, even in the “free speech” United States.

We have been gratified to see the growth and successes of assertive citizen lobbies. Minority/homeless/children’s/gay and other rights movements, MoveOn.org, Public Citizen, Common Cause (for political reform), AARP and Gray Panthers (for older Americans), and the various tax reform movements are powerful evidence that assertion does work! And there may be no more important arena for its application than overcoming the sense of “What’s the use? I can’t make a difference,” which tends to pervade the realm of personal political action.

Social institutions change slowly. Colleges and universities, governments, political institutions, and international conglomerate corporations often resist change until conditions become so oppressive that some people consider it necessary to become aggressive in pursuit of their goals. Sadly, they may take to the streets in aggressive protest, vandalize property, or even hurt other people in order to make a point. Yet such institutions tend to dig in and resist violent change; they are most likely to respond favorably to persistent assertive action.

Those who have been carefully taught by family, school, and society not to speak up or demand their reasonable rights may feel powerless to express themselves or highly anxious when they do stand up to be counted. We look forward to the day when most families, schools, businesses, religions, and governments encourage individual self-assertion and stop limiting self-fulfilling actions. We love it when frustrated individuals and groups seeking change develop assertive alternatives in pursuit of their goals.

After all, each of us has the right to be and to express ourselves and our needs and to feel good (not powerless or guilty) about doing so, as long as we do not hurt others in the process.