Chapter 21

Dealing with Difficult People

Don’t interrupt me when I am interrupting!

— Winston Churchill

You know the type:

- He leans on your desk, glares, and says loudly, “Just how long is it going to take me to get some help around here?”

- She comes over from next door whining, “Are you folks ever going to clean up your yard? You know, your place is the only one on the block that…”

- He calls your business and demands immediate service, an extra discount, and extended terms. “And if you can’t help me, I want to speak to the owner.”

- She can’t wait to corner you at the open house: “Did you hear about Fred and Betty?” she hisses. “Wilma told me that they…”

What is a “difficult person”? Anyone who doesn’t behave as expected. We do, after all, have some unwritten “rules” about appropriate behavior in our society: be fair; wait your turn; say “please” and “thank you”; talk in conversational tones and volume. Difficult people ignore those mores or act as if they are exempt, often while they expect you to live by the standards they’re flaunting. They’re usually loud, intrusive, impolite, thoughtless, selfish, and, well, difficult!

What do difficult people get out of being that way? A workshop participant gave one of our all-time favorite answers to that question: “The biggest cookie.” They also usually gain control, get their way, and get attention.

Why do we give these troublesome folks what they want? Well, for one thing, it’s usually easier than hassling with them. Most of us don’t have the skills, the time, the energy, or the inclination to try to put such people “in their place.” Sometimes, they show up in a business context, where the policy may be that “the customer is always right.” (Incidentally, we don’t happen to think that’s an enlightened perspective. Nobody is always right. A more workable view is that “the customer is always the customer” and the business is advised to treat customers well, fairly, and promptly.) Other times, it seems more trouble than it’s worth to try to confront such people. It’s highly unlikely that you’ll change them, anyway, and you may even get into trouble for taking them on. So what to do?

Actually, there are a few approaches that can pay off. In this chapter, we’ll consider some of the possibilities.

What Do You Think?

What are your thoughts when a “difficult” customer, neighbor, or coworker confronts you? What goes through your mind?

- Here comes that S.O.B. again.

- Uh-oh, I’m in trouble now.

- What does he mean?

- We’ve got to fix that problem.

- Let me out of here!

- No problem — I can handle it.

- Take a deep breath.

- How embarrassing!

- That’s the funniest thing I’ve heard today.

Your thoughts set the scene for how you’ll respond to a difficult situation. Consider your own first reactions — and reread chapter 10 for ideas on developing more constructive thought patterns — as you take a look at the options for action outlined below.

How to Deal with Bozos

The following discussion offers a “smorgasbord” of action steps you can take when confronted by someone who’s trying to push you around. Draw on those that seem to fit your style and life situation, and put together a response plan for your own “difficult people.” You may never need to fear them again!

1. Changing Your Cognitions, Attitudes, Thoughts: “It’s All in How You Look At It”

Preconceptions, attitudes, beliefs, prejudices — all kinds of preconditioned thoughts are influential in determining our responses to daily situations. Those ideas may be about the way life is in general, the way your life is, or the way this particular person is.

For example, if you believe that life is fair, that things work out for the best, and that people are basically good, you’ll probably respond very differently than you would if you believed that life is not fair, things usually go wrong, and people are no damn good.

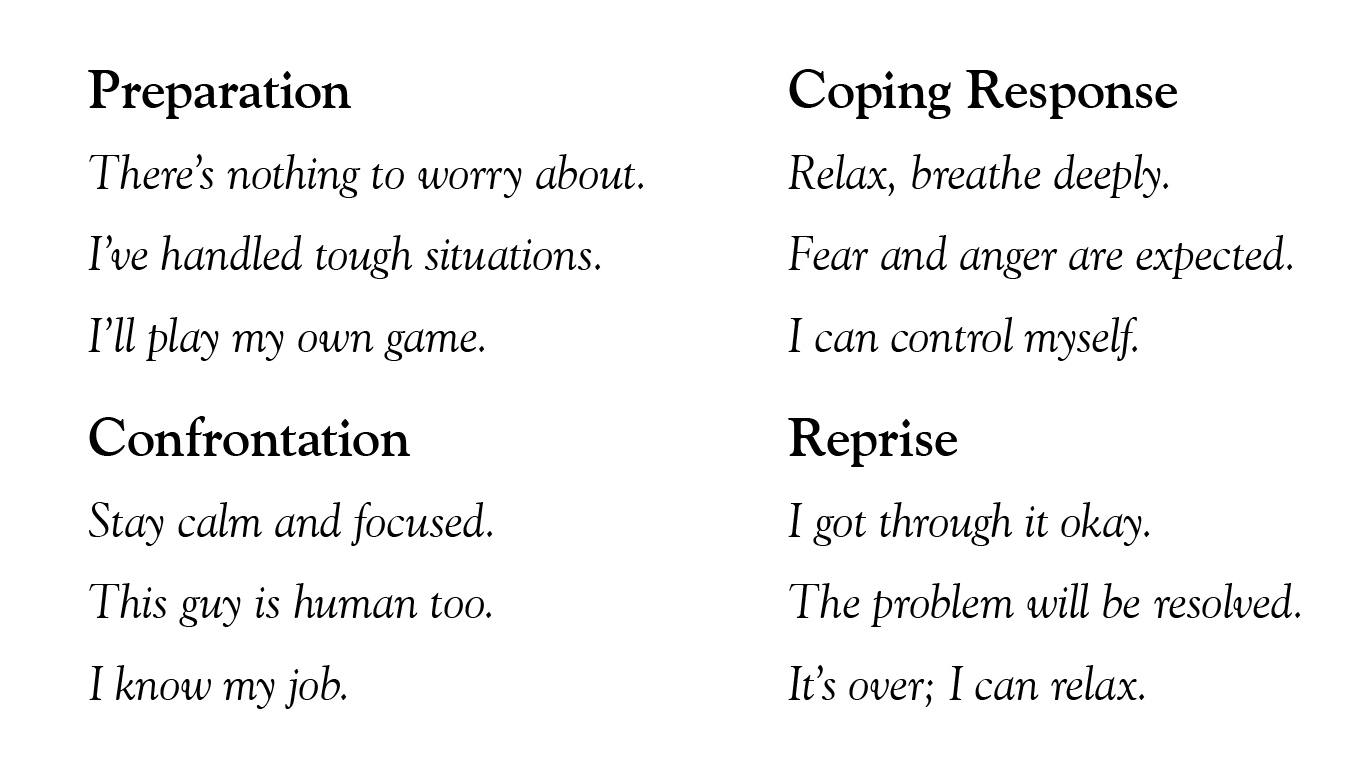

Stress inoculation (first discussed in chapter 10) is one procedure for dealing with cognitive responses. It involves systematic development of self-statements that will help you change your thoughts related to specific situations and people. The following examples are grouped according to four stages of a difficult event.

2. Dealing with Your Anxiety: “Dentist’s Chair Syndrome” or “If You’re Going to Get Drilled Anyway, You Might as Well Lie Back and Enjoy It”

A hostile confrontation usually causes the adrenaline to pump — at least at first — and raises the anxiety response. There are several actions on the “anxiety track,” including:

- Run away

- Tense up and freeze in place

- Relax and breathe deeply

- Systematic desensitization (preparation before an anxiety-producing event by deconditioning)

Refer to chapter 11 for helpful ideas for dealing with your anxiety before and during a difficult situation.

3. Taking Direct Action: “Don’t Talk to Me Like That!”

Assertive and aggressive responses fall into this category of action options: standing up to the attacker, saying you will not put up with such abuse, asking why he is so upset, ordering him out of your office, asking who the hell he thinks he is, telling him to go to hell, and so forth. Handling the situation this way involves facing the person directly; speaking up in a firm voice; using posture, gestures, and facial expressions that appropriately convey your determination not to be pushed around; and taking the risk of possible escalation. “When you come at me that way, I’m not moved to do what you ask.”

4. Syntonics: “Tune In, Turn On, Talk Back”

We discussed “verbal self-defense,” developed by Suzette Haden Elgin, in chapter 8. Syntonics procedures involve getting in tune with the attacker, acknowledging her point, and indicating your empathy with her emotion — but not giving in. Techniques include:

- Matching sensory modes (sight, smell, hearing):

“Do you see what I mean?”

“I hear you.”

“That doesn’t suit my taste.”

- Ignoring the bait while responding to the attack:

Attack: “If you really wanted to do a good job…”

Response (ignoring bait): “When did you start thinking I don’t want to do a good job?”

Psychotherapist Andrew Salter, our late friend, said it this way: “Never play another person’s game. Play your own.” This process is a sort of “applied go with the flow” — letting the other set the pace and style, but not going along with her or his intent. Your action is firm but not oppositional. Such behavior makes you definitely not “fun” to pick on. Your objective here is to take control — to play your own game.

5. Lifemanship: “What’s That on Your Cheek?”

Stephen Potter’s “lifemanship” systems, including “one-upmanship,” offer ways to throw your antagonist off-balance. In his books, Potter suggests, among other things, getting the advantage before you are attacked:

- “Is something wrong?” (looking at a spot on the other’s forehead)

- Staring at some spot on the other person without saying anything, then denying — when asked — that anything is “wrong.”

- “That ball was out!” (in tennis)

- “Of course I had a reservation, guaranteed on my Visa.”

- “When I had lunch with the lieutenant governor last week, he suggested…”

6. Solutions: “No-Fault Insurance”

Here, your response is to ignore any emotional content of an attack, to simply deal with the substantive issues involved, and to seek solutions to the problem:

- “I can see we need to work out a solution to this situation.”

- “There really is a problem here. What do you suggest we do to avoid similar circumstances in the future?”

- “Let’s take a look at the data and see if we can come up with some answers.”

7. Withdrawal: “The Engagement Is Off!”

This approach involves either saying something simple and direct, such as “I’ll be glad to discuss this with you another time, when you’re not so upset,” or saying nothing at all and simply leaving the scene.

Some situations are not worth the energy it would take to resolve them at the time. This is especially appropriate when the attacker is rational but totally unreasonable. Confronted with a violent person, of course, your best strategy is to escape without saying anything.

8. Humor: “And the World Laughs with You”

Humor is almost always appropriate. It works best, of course, if you have a natural joking style and are good with one-liners, so you can disarm anger or attack with a funny line. It doesn’t mean telling jokes that might be funny under other circumstances.

Ask yourself: How would Jon Stewart handle this? Ellen DeGeneres? Steve Harvey?

9. Knowing Your Audience: “Not in Front of the Children”

“A time and a place for everything” applies here. You may wish to offer an opportunity to discuss the matter at length in private, but point out your unwillingness to pursue it in front of others, since both parties may find it awkward and a rational solution may be less likely.

10. Requesting Clarification: “Say What?”

This approach amounts to a simple, direct request for clarification (especially if it is repeated a couple of times), which can de-escalate a situation and help put you in control.

- “I’m not sure I understand.”

- “What exactly is it that you want?”

- “Would you explain that to me again?”

Again, your goal is to gain a measure of control, to prevent manipulation, to play your game.

11. Changing the Scene: “Build a Level Playing Field”

Particular individuals — maybe even some in positions of power — may regularly, predictably cause you grief. Or perhaps specific reoccurring situations — such as a routine on your job — are likely to produce certain kinds of problems. Then you may need to work with others to establish some institutional or departmental support systems that “cut ’em off at the pass.” Such systems might include:

- Behavioral ground rules for meetings

- Standard procedures for how you’ll serve people

- Policies you apply uniformly

- Collective/departmental action to effect institutional change

The Situation Is Serious, but Not Hopeless

Here is a summary of guidelines and procedures that can help when you’re confronted with a particularly difficult person or situation:

- Direct your efforts at solving a substantive problem, not “taking care of” a difficult person. If you insist on one “winner,” there probably won’t be one. (And if there is, it may not be you!)

- De-escalation of loud voice and angry gestures is usually best accomplished by modeling; lower your own level of emotional behavior, and you’ll probably affect the other person’s actions. (Do you remember the mirror neurons we mentioned back in chapter 1?)

- Your approach to these situations should be your own as much as possible — a good fit with your natural style. All the ideas here are legitimate, but only some will work for you.

- Preparation in advance is a big help. Learn deep breathing and relaxation techniques, cognitive restructuring, and assertive skills. A confrontation is not the time to start practicing!

- If you’re going into a situation where it’s likely you’ll confront a difficult person, set up some ground rules in advance to cover typical problems (like time limits for “talkers” in a group meeting).

- If there are particular individuals in your life who are predictable problems, you can practice methods that are custom designed for responding to them.

- Get to know yourself and your own triggers for emotional response. As psychologists Albert Ellis and Arthur Lange suggest, find your own buttons, so you’ll know when they’re pushed!

- So-called I-messages really can help — take responsibility for your own feelings without blaming the other person. (For more on this, refer to chapter 8.)

- Acknowledging the other person’s feelings while seeking a resolution is usually helpful. (“I can see you’re really upset about this.”) But be especially careful not to patronize or come off sounding like a too-empathetic counselor.

- It’s often not possible to solve a situation on the spot. Look for a temporary way out so you can seek a solution in a calmer moment.

- Remember, you do have some options for action. Any of them can cause you more trouble with a difficult person if you become a manipulator, so apply them sensitively — but firmly — and with the main goal of getting on with your life.