Two

Hands on my hips, I pondered the body that lay before me. Eighteen years as a cop, ten profiling murder scenes, I’d seen stranger killings, but this one was up there near the top of the bizarre list. Overhead, I heard a crackling, drawing my attention to the strong, gnarled branches of an oak tree, draped with long, flowing, feathery tendrils of pale green Spanish moss. Midway up perched a dark, hooded figure, watching, beady eyes staring down at me, waiting.

“I hate vultures,” I said with more intensity than I’d intended. I grabbed a tissue out of the back pocket of my black Wranglers to mop up a bead of sweat tracing its way down the back of my neck. When that didn’t help, I gathered my shoulder-length, straw-colored mane in one hand and hoisted it up, hoping for a breeze to cool the exposed skin. No luck. “Damn buzzards are the ugliest birds.”

“Gotta say I agree, Lieutenant,” Sergeant George “Buckshot” Fields growled back. In a similar pose standing beside me, Buckshot had a look of pure disdain on his broad, mustached mug. A big, sinewy man, he took up more than his share of space. I’m not a small woman, a little over average height and a good weight, not heavy but not too thin, a little broad through the hips, yet my fellow Texas Ranger towered over me. When I said nothing, he went on, contending, “Those damn birds are even uglier than my ex-wife, and that’s saying a mouthful.”

I looked over, and the sergeant sneered, exposing saliva-coated teeth, yellowish brown from the plug of tobacco he gnawed religiously. He had a roguish sparkle in his intense dark eyes, seated under the ridge of a prominent brow. “That gal, she could stop a train with her face,” Buckshot said about the woman he’d once loved. “And don’t get me started on her figure. Not sure she had one.”

“You forget, I know Peggy,” I said with a blank stare. “Beautiful woman, at least on the outside.”

Buckshot shrugged. We both knew that he hadn’t forgotten, just felt like grousing out a bit of frustration.

“Yeah, Sarah, that’s true enough. Most likely why she left me,” he said with a sheepish grin, ruffling up his wavy salt-and-pepper hair, wet with perspiration. He mopped off his forehead with the back of his hand, thoughtful. “Can’t blame a man for complaining, way she hightailed it out of here.”

I nodded, figuring he had a point. A year earlier, Peggy had taken up with one of Buckshot’s best friends, a guy he’d known for decades who’d won somewhere around four million in the state lottery. After the divorce, they moved to Southern California, where Buckshot said the happy couple lived in a house with a maid and a kidney-shaped swimming pool. “Lieutenant Armstrong, you want me to kill that damn bird?” the sergeant asked, cocking a pistol fashioned out of his right index finger and thumb and pointing at the vulture hovering above us. To make sure I understood, Buckshot followed it up by suggestively placing his hand on the 9 mm in his holster.

He looked pleased at the idea, and I momentarily considered the possibility, sizing up the repulsive thing and figuring the world wouldn’t miss one homely scavenger. But then, maybe it would. After all, the vulture wasn’t doing anything it wasn’t designed to do. And it was waiting politely, not in a hurry for dinner. I couldn’t think of a justification for killing it simply for being what nature intended. “Nah,” I said. “Leave him. When we’re done here, it’ll call in its friends, have a party, and help clean up this mess.”

It was then that the sergeant voiced what so many on the Gulf Coast felt, the uneasiness that comes from impending danger. It makes your senses keener, but it comes along with a sense of dread. “Guess you’re right. Damn ugly, but those birds don’t usually bother me. It’s this blasted, never-ending heat. It’s long past time for summer to pack it in for the year. Don’t know if I believe in all that global warming mumbo jumbo, but this is the hottest October I remember. And I don’t much like having that damn storm out in the Gulf. Never cared much for vultures, but I like hurricanes even less.”

“Yeah,” I said. “You’ll get no argument from me.”

The hurricane had a name, Juanita, and it had been trekking toward land for the better part of a week. An impressive category four with 145-mile-per-hour winds, it measured more than four hundred miles in diameter, and it was deadly. On satellite photos, Juanita filled much of the Gulf of Mexico. Two days earlier, the storm had flooded and ravaged northern Cuba, leaving it in shambles and putting thirty-five men, women, and children in their graves.

Stalled over the unseasonably warm Gulf waters, Juanita grew stronger with each passing day. It was a nervous time, too early to know where Juanita would come ashore, despite the best efforts of the predictors. “So far it looks like it’s heading farther south. They’re not saying it’ll hit us,” I pointed out. “Still, with hurricanes you never know.”

Buckshot nodded, and I expressed the dilemma of living in hurricane country: “Sure don’t want it here, but I’d hate to wish a killer storm like that on anyone else.”

“I know what you mean,” Buckshot said with a sickened frown. “I can’t think of any good place for a hurricane but spinning to its death out at sea.”

At that, Josh Braun sauntered over. While we discussed vultures, the unseasonable heat, and hurricanes, Braun had been on his cell phone, checking in with his insurance people. He had a claim to file, no doubt about that. “Well, Sarah, my agent’s going to give you a call. He’ll need a copy of the police report. But the big question is, what the hell happened here?”

Thick-necked and stubble-faced, Braun had graduated a few years ahead of me from high school, which I figured placed him in his early forties. Folks in my hometown, Tomball, worship local football players with the intensity much of the world reserves for movie stars. Braun had been the star quarterback and a notorious ladies’ man, deflowering, legend had it, most of the high school cheerleading squad. Middle-aged, overweight, and balding, he still had a certain cachet as the head of a family that owned twenty-six hundred prime wooded acres grazed by the largest herd of cattle in the hills north of Houston.

In the past decade, the city had gobbled up ever-larger pieces of Tomball, a once sleepy burg half an hour north of Houston. Six months earlier, my mom had been approached about selling the Rocking Horse, our place, where she boards horses. Rumors said developers were clamoring to buy the Braun family’s cattle ranch, the last major spread close to the city that remained undeveloped. Mom turned down the offer for the Rocking Horse. But folks had bets on how long the Brauns would hold out and how high they’d drive up the price. I wondered if what we were looking at was in any way related.

“Anyone have a reason to be mad at you, Josh?” I asked. “Could this be someone’s way of persuading you to sell your land?”

The rancher mulled that over for a few moments, as if considering the likelihood. Then he shook his head and waved his right hand, pushing the thought aside. “Don’t think so. I really don’t. We’re talking to a few folks interested in buying the place, sure, but nothing all that serious, and there’s been no hard feelings. At least, not yet.”

I thought about that, then asked, “Okay, what about anyone else who has a reason to be teed off at you? Somebody you fired or had a run-in with, or someone you’ve wrestled with in the past?”

This time, Braun grimaced, furrowing his heavy brow. Time passed, and no one talked, until he again shook his head. “Well, Sarah, I guess there’s nearly always someone mad at me,” he admitted with the certainty of a man who’d been in more than his share of sticky situations, including, if the other rumors were true, with the angry husbands of a good number of lovers. “But for the life of me, I haven’t got a clue who’d be bastard enough to do something like this. You know how much that damn animal was worth?”

All three of us stared down at the bulky beige-and-tan body splayed out on the ground. Someone had drawn a circle around it in the coarse, red-brown earth. Habanero, Braun’s prize-winning Texas longhorn bull, lay in the center, dead long enough in the incubator-like heat that the pasture smelled of decomposition and flies buzzed the beast’s face.

I sensed the sergeant wanted to put Braun on notice. “I believe you already told Lieutenant Armstrong and me how much you figure that animal was worth,” Buckshot said, never one to belabor a point. He stopped to spit a cheek full of tobacco juice onto a pile of red sumac leaves. “Actually, Josh, I think you’ve told us a few times how much that bull of yours was worth.”

The rancher grimaced. “I don’t mean to repeat myself, Sergeant Fields, but I want you both to understand that I’ve suffered a sizable loss here. This animal was valuable,” Braun said, his voice impatient. “Now that I really think about it, I had Habanero underinsured at a hundred grand. The past couple of years, we shipped straws of that bull’s semen across the world. Last week we even got an order from Australia. That animal was a gold mine, and we had a lot more years to cash in on him.”

When we’d been summoned by a frantic call, I’d been reviewing cases for other agencies. As the Texas Rangers’ only criminal profiler, I assess evidence and work on investigations with law enforcement agencies across the Lone Star State. In all the other cases, the victims were human. Responding to a scene where the deceased was a nine-year-old longhorn? Well, I had to admit this was the first time I’d had that pleasure.

Shaking his head, Braun folded his arms across his chest, steadfast. “I shoulda been more careful, kept Habanero closer to the rest of the stock, instead of letting my prime sire wander so far out,” he said, sounding like a man plagued by regret. “Least I should have done was made sure he was fully insured. I’m going to have to rethink what I’ve got in insurance on my stock, if this sort of thing is going to go on.”

Then he said what we were all wondering: “Who the hell would murder a bull just to paint some blasted symbol on him? How’s that make sense?”

Not sure, I didn’t answer, which appeared only to irritate the cattleman more. “Is this some kind of gang ritual or something? Some city kids from Houston come up and do this?” Braun asked, looking perplexed. “Sarah, I could use some answers here.”

Not eager to commit until I had a shot at being at least close to right, I kept my mouth shut and considered the possibilities. At first, the men followed my lead and no one spoke. Finally Buckshot spit again and then, it appeared, felt compelled to defend my honor. “Lieutenant Armstrong here’s real good at figuring these types of things out. This here’s a strange one for sure, but you give her a chance and she’ll decipher it. That I guaran-damn-tee you.”

What was apparent was that both men were angry, and not surprisingly so. To the rest of the world longhorns might seem like just livestock, but in Texas the animals, descendants of Spanish cattle introduced to the New World by Christopher Columbus, verge on sacred. This isn’t like India. We eat longhorn meat all right. I haven’t met a lot of Texans who don’t enjoy a well-marbled rib eye. But the breed is part of our heritage, our image, and we take the animals seriously.

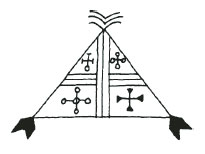

Wanting a closer look, I crouched down, covering my mouth and nose with a tissue, as much for the smell as to keep away the flies. The symbol was drawn on the dead bull’s hide in thick black ink, painted with broad downward sweeps to accommodate the beast’s short, soft hair. Sizing it up, I noted that the diagram was made up of a large triangle divided into four parts, each holding a cross, the tips of the intersecting lines ending in circles. At the top of the main triangle were three lines, double-arched and resembling birds in flight. Pointing at the corners of the triangle’s base were figures that resembled arrowheads.

Was it some kind of Native American reference? Or a gang symbol, as Braun suggested?

“Sergeant, I need paper,” I ordered, and Buckshot complied, handing me his lined spiral-bound report notebook and a pen. We’d already photographed the bull’s corpse, including multiple close-ups of the drawing, but in college I was a psychology and art major, and sometimes sketching helps me analyze what I’m seeing. Abandoning the tissue, which wasn’t helping anyway, I swatted away flies as I drew the symbol, outlining it and then filling in the solid parts with the black ink. While I worked, I thought about the animal’s coloring, buff with scattered caramel-colored spots. The interesting thing was that the area where the symbol was drawn, smack on its side, midway from head to tail, was completely pale. That was obviously the part of the animal the killer cared to preserve, since the bull’s head had been nearly blown away. Most of the skull had been cratered and emptied out, blood and brain matter splattered across the dirt and the side of a nearby oak tree, the one the vulture was using as a perch.

“I know this beast isn’t a human, but I need you to take the case seriously,” Braun said, looking even more disgusted. “I raised Habanero, and he’s worth more to me than money.”

A stand of pines bordering the pasture filtered the searing rays of the sun. I leaned over the bull, on closer inspection, and noticed bits of lead pellets and wadding, the ingredients of a shotgun shell, mixed in with the brain matter fanned out behind the bull’s head. Braun described Habanero as an even-tempered animal, not afraid of humans. I figured the killer walked right up to him, raised the shotgun, and pulled the trigger. Habanero’s head exploded, and the animal maybe staggered some or simply dropped where he stood. The killer painted the symbol, whatever it was, on the carcass with some kind of thick black marker and then dragged a stick or something through the dirt, to draw the circle around the bull. It seemed a vile thing to do to any animal, to sacrifice it for no apparent reason, not food or even sport.

“Habanero’s value makes this a serious offense. We’ll have to consult the district attorney’s office, but to my mind, this person robbed you of valuable property, and we’ll view this as a high-level felony,” I said, noticing Braun relax as he nodded in agreement. “We’ll do our best to investigate.”

“That’s all I’m asking, Sarah,” said the aging jock. “Just that you look carefully at this case, don’t shelve it because it’s about a dead animal and money.”

“The sergeant and I will do our best,” I reassured him, pushing up and again standing between the men. “There’s a professor at A and M, one who works with bugs. She’s the best in the state, and she may be able to analyze the larvae on the carcass to give us a rough estimate of time of death. And I have a crime scene unit on the way. It may be tough to pull up a print since the bull’s hide is covered with hair, but we can try. I doubt it, but they may decide to take the bull in for autopsy.”

“That wouldn’t make that old guy happy,” Buckshot offered, nodding up at the vulture. “I think he had big expectations.”

All three of us looked up at the buzzard in the tree and frowned. “Damn birds,” Braun said. “Guess I shouldn’t begrudge him. That’s how we knew something had happened. We saw them circling. We shooed the others off. That particular vulture refused to go.”

Looking around the setting, a remote location far from the ranch house, I could see the wheels turning when Buckshot asked, “You figure the guy did it way out here to hide the thing?”

It had never occurred to me that the killer wanted to conceal his handiwork. It seemed obvious that he wanted folks to notice. Why else choose a prize-winning bull to slay? If he’d just wanted the thrill of shooting a cow, there were plenty out in the fields. Folks would miss them, sure, maybe report the killing to the local police, but they didn’t belong to bigwig ranchers who’d call the governor and request that the Texas Rangers investigate.

“No. I don’t think so,” I said to Buckshot. “Where’s the fun in leaving behind an obscure message on a dead animal’s hide if you don’t want anyone to find it? My guess, it was just the opposite, that this lowlife figured the bull was expensive enough that someone would go looking for him.”

“Guess you’re right,” Braun said. “But it sure is a puzzle.”

“I can understand rustlers, stealing animals and selling them to pocket the cash. This I don’t get,” the sergeant said. “The bull was just a way to send some kind of message?”

“Yeah. The way it looks, this is all about that drawing,” I said, pointing at the symbol.

“Sheesh.” Braun looked disgusted, furious at the culprit. “When you find the bastard, tell him to send an e-mail or a letter next time. Leave my livestock alone.”

“We’ll do our best, Josh,” I said. With that, I started walking back to where we’d left our vehicles, fifty feet away in the cattle pasture. Careful where I put my boots down, I explained what would happen next, that Buckshot would stay at the scene to oversee the CSI unit and work with the entomology professor. We were still discussing plans when my phone rang.

“Sarah,” David Garrity said.

I was glad to hear his voice, and I reacted with a slight quickening of my pulse, then silently scolded myself for my response. David is an FBI agent, a fellow profiler. We’d been officially dating for about six months, and I’d grown to enjoy hearing him say my name. At first, it had all seemed relatively simple. We enjoyed each other’s company, maybe more than we were ready to admit. At least, I suspected that was true from my perspective. But then, a month earlier, a wrinkle had developed, an unforeseen complication we had yet to navigate our way through.

“Yeah, hi, David,” I said, glancing at my watch. Half past six. I’d told him I’d be ready for dinner at seven. I had to get home, get the cow dung off my boots, and change into something at least flirting with feminine. It was part of the new me. David hadn’t complained about the old me, but I was taking a stab at trying at least vaguely to dress like a girl, especially under the current circumstances. I thought about my hair, frizzy. I’d need a shampoo.

But then, maybe not.

“I can’t make it. At least not at seven,” he said. “We’ve got a kidnapping, a little boy, four years old, from a park in Houston. The Amber Alert is out, and I’m on my way to the scene.”

“Where?” I asked, feeling my body tense. I’ve never liked missing kid cases, anything involving a child, really. And there’d been a rash of them lately, all little ones. The others had turned out badly.

“Northwest side,” David said.

“Maybe the kid just wandered off into the park?” I ventured, getting a sick feeling that betrayed the optimism in my question. “Are you sure it’s a kidnapping?”

“We’re not,” he admitted. “Might not be that at all. They’re doing a preliminary search of the park, but so far no little boy. The sheriff’s department responded to the 911 call and requested FBI assistance. The deputies on the scene tell me the mom’s a bit odd. She waited a full hour before she called it in. Her husband was at the scene, and he says she wanted to search the park on their own, before bringing in the police. We’re looking at her pretty hard.”

“You’ve got a mom, though,” I said. “This isn’t like the others?”

“Yeah,” he said. “We’ve got a mom and dad, an ID on the kid. It’s not like the other two, the unknowns.”

“That’s good,” I said, thinking about the two partial skeletons of children found over the past year and a half. This case was different, but I wasn’t ready to give up on the possibility that David’s missing child case could be related. “This kid is about the right age to be connected to the others, though.”

“I thought about that,” David said. “But nothing else matches. This isn’t a case of unidentified remains. Our boy’s been reported missing. And like I said, we’ve got parents and an ID.”

I thought about that and decided I was undoubtedly grasping at straws, hoping for any possible clues to the deaths of the unidentified little ones, unsolved cases that had been haunting me for months. “You’re right, of course. You need any help? Should I meet you there?”

“No. We’re okay. The sheriff’s department is flooding it with talent. Half of major crimes is investigating. I’ll call you later.” He paused and then added, “Sarah, I still hope this’ll be quick, that we’ll find the kid and have time to get together, but it might be pretty late.”

“No problem. Hate to think of the little guy lost or worse. I’ll head home and get ready, in case it works out, and wait to hear from you. Let’s see what happens.”

“Great. I’m sorry. I was looking forward to tonight,” David said, sounding genuinely disappointed.

“Me too,” I admitted. Maybe I had more reason than he did to regret calling off our date. “I hoped we could have that talk you’ve been postponing.”

“Ah,” he said, his voice soft, regretful. “Yeah. I know. The truth is that I’m not sure I’m ready. I haven’t really figured it all out. But I understand why you’re impatient.”

Silence on the telephone, then David said, “I’ll call as soon as I know what’s up.”

“Okay,” I said. “Now go find that kid.”

“Fingers crossed,” he said.

When I clicked off the cell phone, Buckshot grinned at me. “You and that FBI agent going to make it legal?”

That’s one of the things about working with strong, opinionated, protective men: as soon as a woman’s dating, they figure she needs to be looked out for and that she needs a wedding ring on her left hand to make it respectable. “Hasn’t been discussed,” I said.

“I didn’t know you were single, Sarah,” Josh said. He stood up straighter and smiled, one of those smarmy, suddenly-I’m-so-interested grins. The legendary philanderer had the audacity to straighten his shirt collar and move closer to me. “You know, I had kind of a thing about you in high school. When I heard you married that Texas Ranger, I figured I was out of luck, since the guy would be a deadeye shot. When was the divorce?”

“No divorce. Bill’s dead,” I said, narrowing my eyes and giving him a cold, calculated look intended to cut off the conversation. Braun took two steps back. People react that way a lot to finding out I’m a widow, unsure what to say. “My daughter and I are living at the ranch with Mom. Bill was a great guy, wonderful father. He died two and a half years ago, and I miss him every day.”

“Sorry,” Braun said. Yet he took only a minute to regroup and then moved closer. He seemed confused when I shook my head.

“Josh, I’m not a high school cheerleader, and you’re not the star quarterback,” I said. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw Buckshot chuckle, enjoying the exchange. “It’s my job to figure out who killed your bull. That’s it. I’m busy, so I’d like to avoid distractions and tie this up.”

I shot the cattleman a smile and then waited. He frowned at first, then shrugged, undoubtedly realizing that solving Habanero’s killing was worth more to him than a flirtation with me. A commotion overhead, and I realized the potential diners had multiplied. Four vultures batted their long black wings, riding the air currents and gliding above us, while two on the ground picked greedily at the carcass.

“Now, about the dead longhorn, chase those buzzards away and get more photos before we lose the light, Sergeant,” I said. “Then guard the scene until the forensic unit gets here.”

“Those birds are going to be more than disappointed,” Buckshot said with a wink. He seemed delighted at the prospect of sending the birds packing with empty stomachs.

“Yeah, well, when it comes to disappointment, there’s some of that going around,” I said, thinking about David’s phone call. “All that ‘best laid plans of mice and men,’ I guess.”

The sergeant and Braun looked at me as if confused, but I didn’t bother to recite the verse or credit Robert Burns. Instead I simply said to the sergeant, “Keep me posted.”