Seventeen

The Westover Plantation lay on the north bank of the Brazos River, a twisting ribbon that takes shape north of Abilene and meanders and bends through Texas, eventually emptying into the Gulf of Mexico. Since its discovery, the river’s been the stuff of legends, and the early Spanish settlers who inhabited this part of Texas called it Río de los Brazos de Dios, in English the River of the Arms of God. That name has always puzzled me. Floating down a river named after “the arms of God,” I imagine a crystal-clear stream. South of Houston, the Brazos is as brown as its muddy shores.

Listening to the radio, I drove across the flat coastal plain, lined by open fields and short, scrubby stands of trees, exposing a nearly uninterrupted dome of brilliant blue sky. A white wooden cattle fence lined the road as I approached the plantation, and a sign at the entrance warned: PROPERTY OF THE STATE OF TEXAS—NO PUBLIC ACCESS.

As Benoit had instructed, I removed the chain loop that anchored the gate, and I entered the gravel road leading to the main house. The road ran between two-hundred-year-old oaks, their branches a canopy so dense that it admitted only narrow shafts of light. As I drove, the shadows and light pulsed through the interior of the Tahoe, as in a theater during an old black-and-white movie. A few minutes later, whitewashed sheds became visible off in the distance, then a straight, austere house with six thick, square pillars. Built in the 1820s, decades before the Civil War, the house was brick painted white, and the double front door must have been fifteen feet high. I walked inside, onto bare pine plank floors that creaked beneath each step, into a parlor. Directly across from the main doors stood another set of double doors leading to the back porch. I’d seen homes built this way before, old structures that dotted the countryside. For more than a century, until air-conditioning, the residents left both sets of doors and rows of tall windows open for cross-ventilation, to soften Texas’s unrelenting summer heat.

“Dr. Benoit,” I shouted. “It’s Lieutenant Armstrong.”

No answer.

The mansion was in a state of disrepair, with plaster separating from the interior walls, showing their core, like the outside of the house brick and mortar. The rooms were empty, upstairs and down, except for lawn chairs with frayed woven green and white straps and a dirty white plastic table, a cooler filled with bottled water. I heard no one, no one answered my calls, and before long, I walked out the back doors along a covered brick walkway, to a shedlike structure. As was common in those days, trying to keep the heat out of the house and fearing fire that could consume the entire mansion, the original residents built a freestanding kitchen. A pot hung in a fireplace below a stone chimney, and the place smelled of mold. The room felt heavy with gloom, the only windows skinned with decades of grime.

Outside again, on a path cut through the underbrush, I noticed stables in the distance. The soft breeze smelled of deep pink roses blooming on a fence line, undoubtedly planted generations earlier by someone long dead. At the stable door, I peered up at the loft and again called out, again waited, but heard no reply. Dr. Benoit had said I would see him working around the place. I felt certain he heard or saw me. Why wasn’t he answering my calls?

On a slight hill, a monument stood in the distance, an obelisk. Up close, its stone was pocked by nearly two hundred years of wear and etched into it were the fading words gone but not forgotten. Running my hand over the once deeply carved letters on the obelisk’s base, worn shallow by wind and rain, I read the name Westover. Surrounding it were gravestones marked with the names and dates of the Westover family, the plantation’s original owners, members of the colony that settled this part of Texas, led by the man considered the Father of Texas, Stephen F. Austin. Piecing together the clues on the markers, I learned that Colonel James Westover was born in 1794 and in 1832 fought in the Texas Revolution. He lived a long life, burying three wives and more than half of his thirteen children. On one grave, it read, “Little Nell, left this earth at three years and three days, succumbing to the fever.”

As I stooped over the child’s lonesome headstone, I sensed someone standing behind me. I hadn’t heard anyone approach, and out of instinct, my hand went directly to the Colt .45 holstered on the rig under my jacket. Quickly I stood and turned, and found myself face-to-face with an angular man I judged to be in his early fifties. His features were finely cut, aristocratic, his hair a tree-bark brown only touched by streaks of gray, combed back in waves, framing deep-set grass-green eyes. His skin was well tanned, as if he worked long hours in the sun; he stood well over six feet and wore a wide-brimmed canvas hat, a white linen shirt, and khakis with boots.

“Lieutenant Armstrong?” he asked, eyes narrowed, questioning.

“Yes. And I assume that you’re Dr. Benoit?”

“Of course,” he said, his manner one of absolute calm. “Who else would be foolish enough to be out here on the plantation with that hurricane in the Gulf?”

“I didn’t see a car when I drove up,” I said, slowly removing my hand from the grip of my Colt .45. He watched, as if amused. I was anything but pleased. “I called out and looked for you, but you didn’t respond. I was beginning to worry that perhaps you weren’t here.”

“My truck is in one of the outbuildings. I like to protect it from the sun.” His expression was blank; it was as if he stared through me. “Unseasonable heat, and now a hurricane. I should be at home, barricading my house, instead of attempting to salvage what may be unsalvageable. Or interrupting my afternoon’s work to talk with you.”

“I do appreciate your assistance. We were grateful for your offer,” I said, and Benoit shrugged, not acknowledging that he was the one who’d offered to see me. I wondered what he was referring to, what might be unsalvageable. “Are you talking about the mansion? It’s been here for a long time, through other hurricanes. Why the concern now?”

“No. Not the house. Follow me,” he said.

As we walked, he talked in a strange, detached monotone, detailing a brief history of the plantation. Before the Civil War, the sugarcane fields were tended to by as many as sixty slaves who harvested more than four thousand acres, first burning away dry brown leaves and killing the venomous snakes drawn to its rich cover. Pointing at round, cast-iron bowls, eight feet in diameter and three feet deep, discarded in a field, Benoit explained, “After the slaves harvested the cane by hand, they used a mule-powered press to crush it, then boiled the juice down in those pots, transforming it into a thick, brown sweet syrup, used for cooking.”

As we walked on, he explained that Colonel Westover’s only surviving son left the plantation to his children, who sold it after the Civil War, when a scarcity of cheap labor made sugarcane farming in Texas unprofitable. After a string of owners, a wealthy oilman purchased the spread in the 1950s, later bequeathing it to the state to be preserved as a historic site.

“Since then, the place has pretty much been left to rot, with only a few coats of paint and a new roof twenty years ago on the main house,” said Benoit as we approached a long, narrow wooden building with doors every ten feet across the front. Benoit stopped in front of the first door, looked at the place for a moment with a glimmer of pride, then motioned for me to go inside. I entered and found myself in a ten-by-ten room, dark, with the only light penetrating through slats in two boarded-up, glassless windows. The floor was compacted dirt, and the walls were the bare frames of the outside siding.

“What is this?” I asked.

“Slaves quarters. An entire family once lived in this room,” he explained with a solemn frown. “Each door is an entrance to another room just like this one. Each room housed another family of slaves.”

“Hard to believe,” I said.

“Believe it,” he said, his face expressionless.

“Is this the building you mentioned, the one that’s in danger of being destroyed?” I asked.

“Yes. This structure was scheduled to be moved next week,” he explained. “It’s slated to become part of Sam Houston Park. I’ve been preparing the area where it will be relocated. Do you know the park?”

“Yes, very well,” I answered. “It’s one of my daughter’s favorite places. We’ve spent many an afternoon there, enjoying the setting and the city’s skyline behind it. It’s high on our list of favorite places for an afternoon picnic.”

“Ah, well, then you understand the allure,” he said.

On green rolling acreage at the edge of downtown, Sam Houston Park is sandwiched between I-45 and Houston’s mountain range of skyscrapers. In the beginning the city’s first official park, over the decades the property became home to various historic buildings relocated by the city’s Heritage Society, most of them dating back to the early 1800s. After being restored, each was meticulously furnished with period pieces, to give visitors the ability to see how their lost ancestors lived. On long, leisurely summer afternoons, Maggie, Mom, and I had eaten lunch on benches under the park’s impressive oaks, then toured the homes of those long dead, a wealthy financier, a freed slave turned preacher, and the quaint old, white-sided St. John Church. Always in favor of big, flashy, and new, Houston is a place that routinely demolishes rather than preserves, and the park is an unusual escape from the frenetic onslaught of modern life, recalling a forgotten time when swings hung from front porches and pies cooled on windowsills.

“The site is perfect, picturesque, on a slope near the pond,” he said, staring at me oddly, his eyes a cold mask, his look contained, as if he were holding himself back from saying more. “We’ve built the piers because in any tropical storm or hurricane, that part of the park, the section closest to the pond, floods.”

My heart beat faster, but I wasn’t sure why, other than that the way he looked at me made my skin crawl. “I guess it’s good you’re not moving it yet, then, with the hurricane perhaps heading our way.”

“Yes, very true,” he said, his voice emotionless. “But once it’s on the piers, it should be safe.”

I waited for him to continue, but he remained silent, his eyes focused resolutely on mine until I felt exceedingly uncomfortable. “That sounds exciting,” I said, wondering about the man with the odd, coldly distant manner. “Moving the building to the park, I mean. It must be exciting watching your plans take shape.”

“Yes, very,” he said, again keeping his eyes on me, as if waiting to see what I would do next. I sensed a curiosity in his expression, as if I were as much a specimen as an old building needing restoration. “If the slaves quarters survive this Hurricane Juanita, we’ll begin the work.”

“Fascinating,” I said, as curious about the man as he was about me. “How did you get into this?”

“I grew up in Louisiana,” he explained, as if he’d been asked the same question often. “In the seventeen and early eighteen hundreds, my ancestors bought and sold slaves.”

“So this is personal.”

“Not really,” he said with a shrug. “It’s the restoration and the history that interest me, not the injustices of slavery.”

That surprised me, but I hesitated to comment, instead saying, “How ironic it would be if now, after surviving so long, this building were destroyed before you could save it.”

“Irony is a good word, just as it’s ironic that you would come to me with your symbols,” he said with the first show of emotion since I’d set eyes on him, a self-satisfied grin.

“Why is that ironic?” I asked, puzzled, feeling with each passing moment more ill at ease being close to Benoit.

“Perhaps ‘surprising’ would be a better word choice, that our paths had crossed through our professor friends precisely at the time you had the symbols to interpret. Surprising that events fell in place that led you to me,” he said, that same thin half smile etched across his face. Then the subject changed. “Before we begin, let me show you what else we found.”

I followed Benoit again, this time toward a door at the far end of the same building. Just outside the threshold stood the leafless skeleton of a six-foot tree, its trunk impaled in the ground. From the branches hung bits of metal and glass, animal and bird bones, branches encased in old soda bottles that had been slipped over the ends. In the sunlight, the glass shimmered clear, green, and some brown, looking ancient and weathered.

“What’s this?” I asked.

“I constructed it myself, out of pieces I found scattered around the place. The slaves made bottle trees like this, believing they protected the household, kept away evil spirits,” he said, fingering a piece of round green glass hanging from a crimped wire. In response to his touch, the tree shook slightly, filling the air with the clatter of clinking glass. “These trees trace their beginnings to the decorating of graves in Africa. Once the slaves landed in the New World, they used bits of glass, bones, and utensils they found on the plantations to build them. As early as the late seventeen hundreds, decorated trees were placed near doorways. Some believed that the bottles covering the tips of the branches kept the limbs from ending, as a way of ensuring that life doesn’t truly end in death.”

“Fascinating,” I said, but he frowned and shook his head.

“Not really,” he said, his expression leaving no room for argument. “Only fools believe a bit of sparkle and the sound of glass and metal in the breeze can keep away evil. You don’t believe that, do you, Lieutenant?”

My body tensed, I didn’t know why. All I said was, “No, Professor. I’m sure bits of glass and metal have no power over evil.”

With that, he again gestured, and we walked through the door into yet another room, this one lined with shelves holding rusted tools and bits of china and glass. “This is why I’m here, to pack these things up and move it all to higher ground. These are artifacts found on the property,” Benoit explained, fingering one, a long, curved hook with a hinge. Opening the hook, he moved closer to me, as if to make sure I saw it, and I felt his breath against my face, hot even in the stagnant air of the steamy afternoon. “This, for instance, looks like an early Christian symbol of a fish, but it’s not. People read false impressions into simple objects. This has no religious value. It’s simply a hook, one the slaves used to hang pots over a fire.”

“Again, fascinating,” I said. Not sure why, but uncomfortable with being around Benoit, especially alone on the plantation, confined so close to him in the tight quarters of the room, I said with a forced smile, “As grateful as I am for the history lesson, I’m here for something very specific. Perhaps I can show you these symbols we’ve found.”

“Of course,” he said, offering a polite nod. Despite its monotone, his voice betrayed flecks of a New Orleans drawl. “I’m happy to look at them and see if they are in my area of expertise.”

I removed the photos from a small black canvas folder I carried and handed them to Benoit. He took his time, looking at each, turning it in different directions, then clearing a shelf so he could line them up one next to the other, to look at them all at once. For what seemed like a very long time, he said nothing. Eventually he chose two, one of each symbol, and placed them side by side, slipping the discards back into the envelope.

“The professor at A and M who referred me to you believes they’re African,” I said, trying to spur on the conversation. “She seemed to think that perhaps you’d be able to tell me what they mean.”

My attempt failed, as Benoit silently assessed the symbols, a taut smile on his lips. He appeared enthralled with them, soaking them in. I had a sense that to him, they were of significant beauty.

“Professor Benoit,” I said, “please, my time isn’t unlimited. If you know something, I’d appreciate your help.”

He turned and looked at me and said, “Of course, you have an investigation to continue, don’t you.”

“Yes, I do,” I said. “And a long drive back to Houston.”

“Please forgive me for my thoughtlessness.”

“Do you recognize them?” I asked.

“Yes. Your professor friend is right. They’re African.”

“Tell me what they mean. Everything you can about them.”

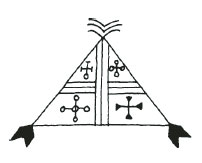

Benoit nodded, then began, “To put it in context, when the Africans were enslaved and transported to the New World to work the plantations, they brought with them customs and symbols from their native homelands. Some of the Africans arrived directly in North America. Others first made stops on islands on the way here, including Cuba. That symbol, your triangular figure, it’s Afro-Cuban.”

“Afro-Cuban?”

“Yes, from the black Cubans, both those who as slaves worked in Cuba and remained there and those who were transported first to Cuba and then, later, to the States to work when the harvesting of sugarcane came to Louisiana and Texas.”

“And what does it mean?”

“The symbol is called Abakuá, the war and blood sign,” he said. “It’s thought to have originated in Nigeria, may have begun as part of a secret society, and it dates back to the Spanish occupation of this part of Texas.”

Pointing at the crosslike figures, he explained that they had no Christian connotation, but rather the circles on the ends of each line stood for drums of honor and symbols of danger. The dark blocks that looked to me like arrowheads, he described as signifying war.

“Why would someone paint this symbol on the hide of a dead bull?”

With that Benoit frowned, as if disappointed in my question. “I thought you understood,” he said, devoid of all inflection. “I can only interpret the symbols. When it comes to solving these crimes, you’ll have to do your own work.”

“But it’s a warning?” I echoed.

“Yes,” he said, sizing me up with resolutely cool eyes. “At least, that’s the way Abakuá is normally used.”

I thought about that, wondering why someone would execute a longhorn to send out a warning and to whom it was intended. “The other symbol,” I said. “Is that a war sign, too?”

“Well, that’s interesting as well. It’s an Adinkra, a symbol used by the tribes of West Africa,” he said, pausing for a moment, as if considering, before going on. “Which symbol did you say was left first?”

“The triangle. The one you’re saying is a symbol of war.”

“Ah, well, that makes sense,” he said. “This person obviously understands the symbols well.”

“Professor, please. You need to spell this out for me,” I urged. I had the impression that he was dragging it out, enjoying my impatience.

“See the shape?”

“Yes, of course. Is it some kind of claw or club?”

“No, it’s called Ako-ben, and it’s a war horn,” he said. “This symbol is meant to show a readiness to join the battle.”

“That’s why the order makes sense, because the first is a symbol of war and the second is a kind of call to arms.”

“That’s exactly right, Lieutenant,” he said, giving me the feeling that I had momentarily, at least, redeemed myself.

“So, tell me who would use these symbols. Have they been claimed by any type of street gang? Maybe a militant group of some kind?”

Benoit appeared to think about that for a moment, as if considering the possibility. “Not that I know of. I’ve never heard of that.”

“Who would know about them?”

“Lots of people, including academics, but really anyone who has studied African and African-American art and culture,” he explained. “And, of course, with today’s technology, a few hours on the Internet are enough to stumble upon these symbols. Scholars have studied and continue to study such drawings and publish their work.”

“I see,” I said.

“You know, when the slaves built the plantations, they often carved symbols into the walls, at the cornerstones. Sometimes they left animal bones between the bricks, in the mortar,” he said. “Some were thought to ensure health and bring good luck. The culture was heavily into symbolism, much of it dating back for centuries.”

“Is there anything else you can tell me about these two symbols?” I asked. “Anything that will help with the investigation?”

This time, his answer was even slower coming. A wry smile, and then he shook his head slightly, again giving me the impression that he found my quandary amusing. “Nothing else, Lieutenant,” he said. “When it comes to figuring out who’s behind this, you’re on your own.”