Forty-two

Maggie ran to me as soon as I stopped the Tahoe in the driveway. It appeared that she’d been waiting on the front porch, and she cried as she wrapped her arms around my waist. “Oh, Magpie,” I whispered, rubbing her back. “I’m so sorry. It’s okay. It’s all okay.”

“I heard about Sergeant Buckshot,” she said, pulling her head back to look up at me with my late husband’s eyes, a soft shade of the palest brown with flecks of green. “I heard about it on the news, how he was shot and his body burned up. They said he was dead, that somebody murdered him.”

“I know,” I said, feeling guiltier with each second ticking off the clock. Despite everything, I should have carved out a few minutes to call her, to try to smooth it over, instead of letting her find out from the television. It was understandable that Maggie was upset. She’d grown up knowing Buckshot, and now he was gone. She must have been wondering if the same thing could happen to me.

“I got worried about where you were, if you were okay,” she said, burying her head in my chest. “Gram said she talked to you, that you were all right, but I wanted to see you for myself.”

“Maggie, Maggie, my beautiful daughter,” I said, holding her in my arms and kissing the top of her head. “Magpie, I’m here, and everything is fine.”

She attempted a small, brave smile. “I know,” she said, the tears rolling down her cheeks. “But I got so scared.”

We stood holding each other in the driveway as the moments slid by. Finally, she released me and stepped back, smiling at me, showing off her new braces, relieved that I was home. Bill had been a Texas Ranger, too, and ever since she’d been a small girl, we’d been honest with Maggie, never trying to deny that our jobs were dangerous. She saw us strapping on our rigs and putting our guns in our holsters before we walked out the door to work. We told her we were well trained and that we weren’t foolhardy. We did our best to minimize the dangers. And maybe most important, that the reason we took chances was to help others. Working the job wasn’t a quest to find excitement. We simply were trying our best to arrest the guilty and save those who could be saved. Then Bill died, but it had nothing to do with the job. Still, I knew Maggie worried. And now with Buckshot’s death, I understood how frightened she was. She’d loved her father and lost him, and any reminder that I could die was too painful to bear.

Looking at my daughter on the threshold of growing into a teenager, I had no doubt that the tie between us was eternal and true. I put my hands on her shoulders. Every year, Maggie grew taller. Every year that passed, every inch she gained, brought us closer to the day she’d separate from me. In two years, she’d enter high school, then, four years later, college. Someday I’d be old, and she’d be the powerful one. But it wouldn’t change what we were to each other. My daughter was one of the great loves of my life.

“Maggie, I’m okay,” I said, leaning down and kissing her forehead. I looked her intently in the eyes. The captain and David were right: I belonged home with Maggie and Mom in the storm. I couldn’t have made that decision, not with Joey Warner in danger, and I was grateful that it had been made for me. But there were things Maggie had to remember. “Please don’t worry about me. I’m careful. I do my best. And I try hard not to take unnecessary chances. I can’t guarantee what’ll happen, but I can guarantee that I will always do my best to come home to you.”

“I know, Mom,” she said, again slipping her arms around me. “I’m sorry I got so scared.”

“Don’t be sorry,” I said, holding her tight. “I get scared, too, sometimes. I love you, too.”

At that, I turned, keeping one arm around her, and we walked toward the house. Mom stood on the porch, watching. “We’re glad you’re home, Sarah,” she said, ruffling Maggie’s hair and kissing me on the cheek as I passed her. “We’ve been looking forward to seeing you.”

The rest of the afternoon dissolved in work. After a much needed hot shower and a change of clothes, I pored over the Warner case files, looking for something, anything that could help, anything we’d overlooked, while Mom, Maggie, and Frieda finished securing the stable and putting fly halters on the horses, covering their eyes. The theory was that limiting their vision would keep them calmer and that if the doors flew open, if somehow—because nearly anything was possible in a hurricane—they ran off, the halters would protect their eyes from flying debris. The most recent reports said that at the rate the hurricane traveled, Juanita would take twelve hours or more to pass through.

Inside the house, Mom had everything in place, from the battery-operated radio on the kitchen counter to a cot with bedding in the living room for Bobby. Before long, Mom, Frieda, and Maggie came in and showered, settling in to ride out the storm.

In the kitchen, Mom worked on dinner, while Frieda, who’d moved into the spare bed in Maggie’s room for the duration, set up an altar in the dining room, on a battered yellow vinyl tablecloth on top of Mom’s old table, decorating it with candles, skull masks shaped from sugar, silk daisies, and small wooden statues of skeletons painted black and white with maniacal grins, some wearing big hats and riding bicycles. Along with Halloween, this night was the beginning of the Mexican festival known as Día de los Muertos, the Day of the Dead, when the dead are thought to roam the earth, visiting family and friends.

When I went to check on them, Maggie and Frieda sat in chairs, watching the candle flames flicker, Frieda’s lips moving silently in prayer. In the center of the memorial, she’d placed a silver-framed photograph of an austere-looking woman with a gray bun and intense dark eyes—her mother, whose body was buried back in her native village in Mexico.

“Maggie, time to help Gram with dinner. She’s making chicken and dumplings, and I bet she could use some help chopping veggies,” I whispered. Yet neither Maggie nor I moved quickly. In the darkened dining room, the altar had a comforting sense of ritual, a reminder of ancient ways, and looking at it gave me a sense of peace.

“Isn’t it beautiful?” Maggie asked.

“Yes, Magpie,” I said, gazing at Frieda’s memorial to the dead and thinking about all those I’d lost, my father, my husband. In the flames, I pictured Buckshot the last time I’d seen him, more than a day earlier at the office, in the meeting with the captain. I’d never see him again, and I already missed him. I pushed away thoughts that I was at least partly to blame for his death. “The altar is beautiful.”

Frieda smiled at me but kept praying.

Bobby arrived just as the sun began to set. The winds had picked up, but we had yet to feel any real effects from the storm. Before long, Maggie sauntered off to the living room, where she turned on an old sitcom, while Bobby took her place helping Mom in the kitchen. He stirred the pot of simmering chicken and vegetables, the rich aroma enveloping the room, while they talked softly, trying not to disturb me as I worked at the kitchen table.

“What’s Sarah doing?” Bobby asked, watching me with maps and pictures spread out on the table.

“She’s trying to find that boy, that little one who went missing from the park earlier in the week,” Mom whispered.

“Oh, they haven’t found him yet?” he asked, and Mom shook her head. “Poor kid,” he said. With that, Bobby went back to stirring, and Mom started cutting up the greens for the salad.

Wondering what was going on in Galveston, I picked up my cell and held down the key for David’s number. I’d been trying to reach him for hours, but all I got was a fast busy. I understood it was probably a function of the storm. Reports said Hurricane Juanita had moved into Galveston with torrential rains, a twenty-foot storm surge, and gusts measuring more than 150 miles per hour. We were already hearing on the radio that power lines were down on the island, and one cell phone tower had collapsed under the strain. I wasn’t so much worried about David and the captain as I was eager to talk to them. The problem was that the longer I looked at the map I’d drawn, one with the location of all four dead bulls and the Warner house, where the fifth symbol had been delivered, the more uneasy I felt about locking in on Galveston as the location.

Searching for answers while telling myself that I had to be wrong, that David and the captain were right and that they’d find the boy, I laid out the photographs and sketches of the symbols, this time lining them up with the locations on the map where they were found, marking each point with a dot. Everything had occurred in and around Houston, the killings of the four bulls on the outskirts of the city and the symbol left on the Warners’ doorstep, inside Houston proper. The more I thought about it, the bigger the knot in my chest grew.

We’d called it wrong. I felt certain of it.

“Sarah, it’s time to clear off the kitchen table,” Mom said. “Dinner’s ready.”

Supper was a quiet occasion, all of us with much on our minds. Bobby raved over Mom’s dumplings, while I let them slide down my throat in silence. They were hot and comforting, and again I was glad to be home.

A worried expression crowding her face, Frieda, who’d remained silent throughout the meal, mentioned the hurricane’s falling on both Halloween and Día de los Muertos. “Do you think that’s a bad omen?” she asked.

“No, it’s not,” Mom replied, putting her palm over Frieda’s hand, resting on the table. “In your festival, isn’t it deceased family and friends who come to visit? Those you’ve lost?”

“Yes,” Frieda said, nodding.

“Then perhaps it’s a good omen,” Mom said with a kind smile. “If those we love are close, they’ll watch over us. They’ll help keep us safe.”

“That’s true,” Frieda said, her face heavy with sadness. “I’ll pray at the altar that my mother comes to protect us.”

Maggie searched my face, and I said, “That would be appreciated, Frieda. We can always use prayers. But we’ll be fine. You’ll see. We’ll be fine.”

Afterward, I reclaimed the cleared kitchen table, again laying out my map and drawings. For hours I pored over them, and time slipped away, until I heard Bobby announce, “Nora, Strings and the reverend just drove up. Looks like they’re taking you up on your offer.”

“Maggie, Strings is here!” I shouted.

I left the papers as they were and went with the others to greet our guests. In the past year, twelve-year-old Strings had shot up, and Maggie’s best friend had to be nearing five feet four inches tall. He’d also let his curly black hair grow longer and traded in his round wire rims for oval glasses that darkened in the sunlight. His dad, the Reverend Fred Jacobs, pastored the Mount Zion African Church down the road from the ranch, an old, clapboard building in the center of Libertyville, a small settlement originally founded by freed slaves during Reconstruction. The spiritual leader of the oldest black church in the area, Strings’ dad was a spindly man with rough-carved features and an angular jaw, who had a perpetual twinkle in his dark eyes.

The reverend and Strings struggled to unload three coolers from the back of their pickup truck as Bobby rushed down and offered, “Let me help you with that.” Mom had already explained at dinner that since we had Bobby’s generator, she’d called Strings’s mom, Alba, and offered to store their frozen food in our extra freezer. Pretty soon we were all pitching in, lugging the coolers into the house.

“Would you like a bowl of chicken and dumplings?” Mom asked. It was rare that anyone dropped in at any hour, even one like this, nearly nine at night, that Mom didn’t offer a plate of food, coffee, or a cool drink.

“Alba’s already fed us, and fed us well,” the reverend explained, patting his midsection. “We’ll be eating a lot in the next couple of days. We’ve got a bunch of refrigerator food to consume before it spoils, if we’re going to lose power.”

“We won’t have a lot, but if the generator works out okay, we’ll bring you what ice we can make,” Mom offered.

“That’s kind of you, Nora,” the reverend said, allowing his eyes to stray over to my paperwork on the kitchen table. “It’s good of you to help us out like this. Can’t tell you how much we appreciate your storing our frozen goods through the storm.”

With that, he fingered a photograph of one of the symbols, the one found on the second bull, Ako-ben, a call to arms. “Maggie, are you doing a school project on Adinkra?” he asked. “You should have asked. I could have helped you. What’s this symbol written on? Some kind of parchment?”

“It’s not Maggie’s. It’s mine, for a case. That’s drawn on the hide of a dead bull,” I explained. “Are you familiar with Adinkra?”

“Of course,” he said, picking up the other photos and paging through them. “On the hide of a dead bull, huh? That seems odd.”

“Yeah,” I said, wondering if there was something about cattle that made the location strike him as strange. “Any particular reason it seems odd?”

“No, no,” he said. “Just seems like an unusual thing to do, is all.”

“Sarah’s working on that kidnapping case,” Mom explained. “The little boy from the park.”

“Saw something about that on the news,” the reverend said.

Maggie and Strings took off for the dining room, where she wanted to show him Frieda’s altar. Before long, I could hear Frieda explaining the symbolism of the sugar skull masks and the small figures.

“That poor little boy,” said Reverend Fred, shaking his head. “What’s his name? Joey, isn’t it? I didn’t know that you still hadn’t found him. Breaks your heart, doesn’t it? A little one like that out there, don’t know where, in this storm. Something like this makes me wonder why there’s so much evil in the world.”

“Yes, it does,” I agreed, sick at the image of the child at the mercy of a madman.

Reverend Fred peered down at the table. “What’s the map for?”

“I used it to plot where the Adinkra symbols were left,” I explained. Technically I should have hidden the photos, since it was all evidence in an ongoing investigation, but something about the way Strings’s dad surveyed the map and the symbols piqued my interest. “Each of those dots on the map represents where a symbol was found. Any ideas?”

He chewed on that for a few minutes, picking up the photos of the scenes where the bulls were killed, then finally placing them back down. “I thought maybe, but no,” he said. “I guess not. It seemed like maybe you had a crossroads going, but it doesn’t look that way. Not with that one off center, not really in the middle.”

“A crossroads?” I asked. “What’re we talking about?”

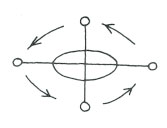

Pointing down at the map, he indicated the dot marking the Warner house, where the note had been left on the doorstep. “Well, if that one wasn’t there, you could connect the other four points on the map, north to south and east to west, where the bulls were found, and form a cross. Then all you’d have to do is draw circles on the ends of the lines, representing the circles in your pictures there,” he said, holding up one of the photographs of Habanero, tracing the circle the killer had drawn around the bull’s carcass in the dirt. Each of the scene photos had a similar circle, drawn around each of the four shotgunned bulls. “He the drew a circle at the intersection of the lines. This symbol is called a crossroads.”

The reverend eyed me to see if I was getting it. I wasn’t, not completely. “You see, there’s a lot of symbolism in both Christian and African cultures regarding crossroads.”

“So tracing the circles found where the bulls were killed onto the map, and then connecting them with two equal lines, I could have a crossroads?” I asked.

“Yeah,” he said. “You sure could, at least the way I’m looking at it. The only problem is that you’ve got that other one.”

I thought about that. The “other one,” the dot marking the Warner house, was different from all the others. No circle had been drawn in the earth. Nothing had been killed or, perhaps, sacrificed, like the longhorns. All the Warners discovered on their doorstep was an envelope holding Joey’s bloody underpants and the sheet of paper with the symbol. That dot on the map, the one the reverend called the “problem,” well, maybe it wasn’t part of the pattern.

“Can you tell me about it?” I asked. “This crossroads symbol.”

The reverend glanced at his watch. The storm was approaching, and we could hear the first winds howling outside. He looked out at the trees, their leaves rustling. The hurricane was making everyone jumpy. “I guess there’s time,” he said. Then he called out to his son in the living room, “Strings, y’all come out here and put this food away in the freezer while I talk to Maggie’s mom, please. We need to be leaving for home real soon.”

“We’ll do that,” Mom offered, but the reverend objected.

“It’s good for children to do their share, Nora,” he said. Then, again, he called out to his son, “Strings, come on out.”

Moments later, Mom, Bobby, Strings, and Maggie were hauling the coolers into the back room, where we had a freezer, clearing a section and unloading the contents, including Alba Jacobs’s frozen homemade pies, for safekeeping. Meanwhile Reverend Fred, whose fiery Sunday sermons brought folks from far and wide to his little church in the country, placed a sheet of unlined paper over the top of the map and plotted the four outer markings, drawing circles around each. He then used a marker and a ruler to connect the northern point with the southern and an equally long second line to join the eastern and western kill sites. Finally, in the center, he drew a fifth and larger circle.

“It seems like crossroads have always interested folks,” he said as he drew. “For Christians, the symbol resembles a cross. You know, long past, folks who committed suicide were banned from burial in the consecrated grounds of Christian cemeteries. So families sometimes took the bodies out to the countryside and buried them where roads intersected, believing the roads formed a cross, and it was as close to a Christian burial as their loved one could get.”

“You said there are African connotations, too,” I reminded him. “Like the Adinkra?”

“Sure,” he said. I motioned, and he looked at the chair I offered but shook his head. I could tell he was worried about time passing and the storm building. “Better not. Gotta be on our way soon, before the weather gets too treacherous. Anyway, the African symbolism has nothing to do with the Christian cross.”

“Tell me about it,” I said. “Anything might help.”

“This type of symbol”—he waved his hand over his drawing—“they’re called cosmograms, geometric renderings of the universe. I’m pretty sure this particular one is believed to have originated in the Kongo, an ancient civilization in Central Africa. The slaves brought it with them to the Americas, and over the decades, it became known as a crossroads symbol. There are different interpretations of what it symbolizes. Some saw the point at the top,” he said, placing the tip of the pen at the upper circle on the map, “as God, or maybe dawn or the sun.”

Tracing the line down to the lowest circle, he went on. “The opposite point, the one beneath, was midnight, darkness, or death, and the line that intersects them, in the case of this map connecting east and west, may have symbolized the earth or water.”

Again I considered the dead bulls, how Benoit had taken the time to draw circles in the dirt around each, circles that resembled those on the map that the reverend had drawn.

“What about the center?” I asked, pointing to the circle Reverend Fred had drawn at the intersection of the two lines, at the axis of the crossroads.

“There are different theories on the importance of the center, but they all allude to a special significance, that it’s a sacred location. These diagrams were sometimes drawn on the earth, traced onto the ground and such, and folks were known to stand on the center circle to take oaths,” he said, excitement creeping into his voice. It was apparent that the symbolism held special meaning for the reverend, as sacred ancient symbols and rituals. “In this interpretation, as in most, it was believed that the center of the crossroads was the point where a man could go to be close to God. It was where God was able to see him.”

“Go on,” I urged.

“Well, there are other interpretations, especially after the slaves were transported to the New World. They began drawing the cosmogram in different places, inside the bricks they made to build the plantations, on the ground out in the fields, sometimes they made them out of stones, even drew them with white chalk on the bottoms of old black kettles they used to melt down the sugarcane to make syrup.”

“A place to take oaths,” I repeated, thinking back to what he’d said. “That’s what the center was for, to be near God.”

“Sometimes, yes. But like I said, there were other explanations. Some say the four circles on the tips of the crossroads symbol represent the stages in a man’s life, from birth to adulthood, to old age, to death,” he said, following along with his pen turned pointer as he mentioned each stage. “When a man stands in the center, it’s also thought that he’s suspended somewhere between life and death.”

Reverend Fred paused, and I sat back in my chair and thought about what he was telling me. It seemed certain that Peter Benoit had grown up hearing his father, an expert on African symbolism, talk about just such things. The old man told us that he’d taught Peter about his work, explained ancient imagery and rituals. Was this diagram a map indicating where he had Joey?

“Like I said, I’ve studied a little on this because it interests me, and what I understand is that many of the African slaves had a slight twist on the cosmogram. They believed that God could see them at the center of the crossroads,” the reverend continued, again pointing at that center circle. “That when they drew this mark and stood at the center, they were as close to God as they could be on this good earth.”

“That’s fascinating,” I said. I thought about all he’d said, how it all made sense in the context of the symbolism Benoit had left behind. But I felt wary, worried about jumping to any conclusion. “Are there other meanings?”

“Seems to me that there are,” he said, closing one eye and thinking on it a bit more. Then he smiled, as if he’d just recalled what had been on the tip of his tongue. “If I remember right, I’m pretty sure some folks back then believed that any man who stood at the center of the cosmogram was of elevated value, that he was to be respected, a man capable of governing others. If my memory is right, some figured that anyone who stood at the center of the crossroads had evolved to such a lofty point that he understood the unknowable, the great mysteries of our world, the meanings of both life and death.”

As Reverend Fred talked, my mind raced. I thought of the string of dead longhorns and the meaning of the third symbol, Aya: “I am not afraid of you.” Benoit had sounded so confident when he’d told me that over the telephone, so superior. Then, suddenly, what should have occurred to me early on took form, as my mind traced back to the heart-stopping moment I first saw Buckshot’s burning body. Benoit set Buckshot’s corpse on fire at the center of a country intersection, in the middle of a crossroads.

“You know, there’s something else,” Reverend Fred said, smiling at me. “I’ve always kind of liked one particular interpretation of the crossroads symbolism. Sometimes, I figure that if I ever need it, and I hope I won’t, it might come in handy.”

“What’s that?” I asked.

“Well, I’ve heard it said by some folks, scholars and the like who study these things, that there’s something else about this right here,” he said, pointing again at the circle at the center of his diagram, the point where the lines intersected.

“What is it?” I asked, sounding perhaps more urgent than he expected. The reverend glanced over at me, and I saw a spark of interest and a slight questioning in his eyes. There wasn’t time to tell him everything, but I needed to know all he could tell me, quickly. A little boy’s life could be ending as we stood talking at the kitchen table. “Please, Reverend Fred. It’s important. It could help with the case. It could help find that little boy. Please go on.”

“Well, I’ve heard that some believe if you’re in trouble, that’s where you go,” he explained, watching me. “I’ve heard it said that anyone who needs help can go to the center of the crossroads and wait. It’s there that God will find you.”