Chapter Nineteen

“That’s enough.” Alan crossed his arms. “This has gone far enough.”

“Do you want me to stop?” They were sitting on the bed facing each other as Rachel told him about her adventure. She had just reached the point where Fulke opened the door.

“Yes. I want you to stop. If you had told me earlier what you were doing, I would have wanted you to stop then. Now I want you to stop now. Stop the detection nonsense; stop the story. Stop.”

“Nonsense?” Rachel remained leaning against the footboard, but her expression grew mutinous. “You’re calling my interests nonsense?”

“I’m calling this whole escapade nonsense.”

Rachel narrowed her nostrils at “escapade,” but he kept going.

“When you first told me that Edgar had requested in his will that you catalogue his books, and that you thought it must be because he’d mentioned at a party that he’d read your work and liked it, I knew you were lying. Who would believe a story like that? But I also know you have this notion that I’m an insanely jealous man, so I thought, ‘All right, I’ll let it go.’ But now you tell me that not only did you begin to think that he might not have died naturally—based on what sounds to me like no real evidence—but also that you, along with Magda, have decided on suspects. And when one of your suspects died, you concluded, despite evidence of suicide, that she must have been murdered by one of your other suspects.”

Rachel was outraged. “You are a jealous man! And we have evidence that it wasn’t suicide!”

“In which case not only have you spent the last month ‘detecting’ ”—he made quotation marks in the air—“without saying anything, but you’ve also spent the last week investigating a real murder—a not-undangerous situation—without telling me, too. And then, to cap it all off, you decided that the best way to proceed was by prying around the inner recesses of your original murder victim’s apartment, whereupon you surprised your current prime suspect in the middle of doing something suspect! And you kept all this from me, your husband, the man you supposedly love and trust and respect more than anyone else. You’re only telling me now because you couldn’t think of an alternate story quickly when I asked why you were so jumpy at dinner. So if I don’t call this nonsense, I’ll have to call it demeaning and hurtful, and in any case, yes, I want you to stop.”

He paused to draw breath. Rachel, her cheeks red, kept her eyes on the sheets. She’d never thought about it his way; she’d just thought it avoided all sorts of awkwardness if she didn’t tell him what she was doing. She was overwhelmed by sudden shame.

“My love,” Alan said, “you are not the police. You are not even a detective”—she opened her mouth to protest—“in any trained way. And you were wandering through what, if you’re right, is a crime scene. On your own. And then you’re surprised by not one, but two possible murderers!”

Rachel wasn’t too ashamed to try to regain superiority. She waved a hand. “Oh, please. I was surprised by a Girl Friday and a butler. That’s hardly a murder about to take place.”

“If your description of everything leading up to your sneaking around”—she opened her mouth again, but once more he didn’t pause—“is accurate, you think a murder occurred there and that this Girl Friday might be the murderer. So your idea of how best to deal with a murder scene is to poke around in it. And when you unexpectedly encounter a possible murderess, your idea of how best to deal with that is to confront her! You can’t say the circumstances suggest murder and then say you’re perfectly safe!” He repeated “I want you to stop.”

Like anyone who has behaved foolishly and been confronted with her foolishness, Rachel’s blood was up. Who was Alan to tell her she’d done wrong? Who’d died and made him Inspector Morse? “Well, I’m not going to stop.”

Alan sighed. “No, of course you’re not.” He took her hand and rubbed her fingers with his own, then gave another sigh. “Well, would you be willing to take a break?” He looked at her. “To allow me to recover from the shock?”

“A break?”

“Just a few days. A week.”

Rachel frowned.

“Including a weekend. So, five business days. Would you be willing to wait for five business days, just to think about whether you want to keep going and how?”

She considered. Taking a break wasn’t a bad idea. She saw now how much her keeping secrets must have hurt him, and agreeing to his request would go some way toward making it up. Plus, although she’d never admit it, she had been frightened by the abrupt end to her exploration, and she could use a few days to catch her breath. Maybe more importantly, she wasn’t yet sure what she’d learned, or what its value might be. A few days to gather herself and sort through the information might be good.

“Fine,” she said. Then, more for show than anything else, “But only one week.”

He exhaled heavily. “Thank you.”

Rachel nodded acknowledgment, then took his other hand and held both on the covers between them. “Now,” she said, “do you want to hear what happened next?”

“Of course.” Alan sat back.

“Well, Elisabeth and I were in the bureau. We didn’t have time to get out of the room and close the door, and obviously if we’d gone in and closed it, Fulke would have heard. It would have seemed as if we were hiding. Plus, we panicked. So we were still standing there when the door opened and Fulke saw us. For a second he stopped—but just for a second. And then he looked at me and said, ‘Madame Levis.’ You would have thought I stood in the doorway to the bureau every day.”

* * *

“And what did you say?” Magda leaned forward. Rachel was telling her the story the following afternoon in Coffee Parisien, a dimly lit café near Rachel’s apartment. Surrounded by chattering students and clusters of Parisians who had paused for an aperitif, Magda was riveted, her café americain untouched before her.

“I said I’d heard a noise and gone to investigate.”

“Did he buy it?”

“How could I tell, with Fulke? He didn’t turn a hair. All he did was look at Elisabeth and say, ‘Mademoiselle.’ ”

But Fulke’s change of focus had given Rachel a second in which to think. “It is a surprise to find her here, isn’t it?” she said brightly. “She was just telling me that she’d decided to come in because she was feeling better.”

Luckily, Elisabeth’s fading blush hadn’t quite left her cheeks; it was just as plausible that she might be a woman with a mild cold. Even better, when she spoke, the constriction of her throat made her sound as if she had a blocked nose.

“Yes,” she said, her voice shaking slightly. “I was just sorting some papers when Madame Levis opened the door unexpectedly.”

It was impossible to tell if Fulke believed this either: his face remained smooth save for a touch of mild confusion. “I see, madam,” he said to Rachel in English, giving one of his small bows. Then he turned to Elisabeth. “Mademoiselle,” he continued in French, “I have a superb tisane for the nose and throat. Allow me to prepare some for you.”

He nodded, then proceeded toward the dining room, his canvas bag of fruit and vegetables tucked under his arm. Casting Elisabeth a look that she hoped said, I’m not finished with you, Rachel hurried back down the passageway.

“So you never saw what was in the bureau.” Magda’s tone was full of sympathetic frustration.

“I know. And those bills!” Rachel shook her head ruefully, “I felt like I was in Northanger Abbey.”

Magda respected her embarrassment with a short silence. Then she said, “Well, do you think you found anything that could be useful?”

For once, the answer was not going to be “I don’t know.”

Rachel cleared her throat. “Maybe.”

“Maybe?”

“Well then, yes.” She paused. “Maybe.” Seeing Magda’s expression, she explained, “I found something Mathilde might have been after. In the bedroom. A sculpture of a dove by Jacob Epstein.”

“The Jacob Epstein?” When Rachel nodded, Magda gave a low whistle. “That must be worth a pretty penny.”

“And it would fit under a coat. Just. It would’ve been bulky, but not too heavy.”

“D’you think that’s what she wanted?”

Rachel shrugged, but Magda’s voice sped up. “It’s not hard to imagine. She kills him for the money she thinks is coming to her in the will, and then when it turns out it isn’t as much money as she thought—as she feels she deserves—she decides to top it up with the sculpture. But Elisabeth catches her on her way in to take it.” Satisfied, she switched focus. “Which reminds me: Elisabeth. You found her rifling through some papers when she was supposed to be out sick? Sneaky.”

“She must have come through the back door when I was in the dining room, and I was concentrating too hard to hear her.” Chagrined, Rachel changed the subject. “But you know what was really weird?”

“What?” Magda leaned forward.

“None of the rooms between the dining room and the back of the appartement have a door to the hallway. If someone wants to go out, they have to do it either from the dining room or from the storage room.”

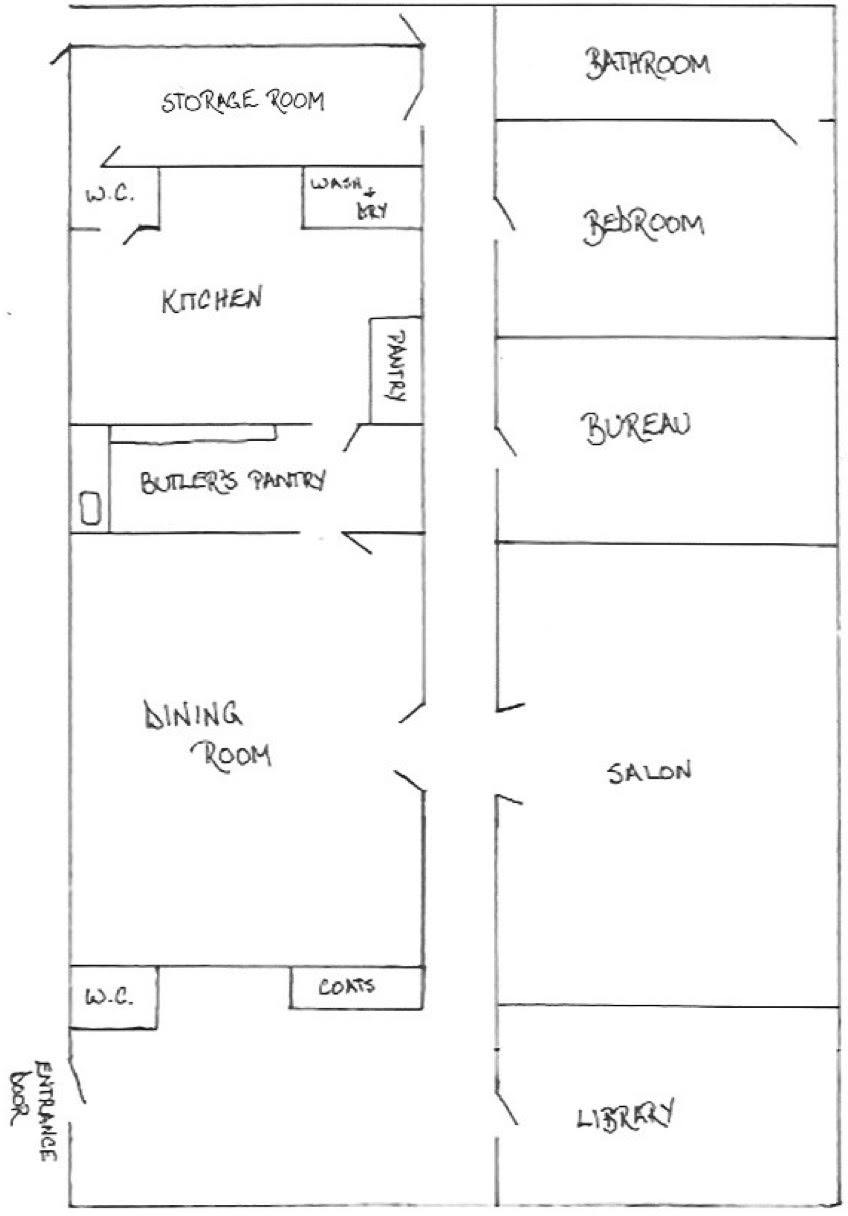

Magda crumpled her forehead, no doubt as she tried to imagine the setup, then pushed a paper napkin at her. “Draw it.”

Rachel sketched a floor plan and slid the napkin back.

“Why would you build your house that way?” she asked.

Magda frowned. “I’ll bet it’s a leftover,” she said finally. “I’ll bet that when the place was first built, that back room was a sort of preparation room—you know, what they used to call ‘offices.’ The servants would come in there and never be seen as they worked their way forward to the public rooms or back to the offices. And if they needed to clean the other side of the place, they could just cross the hall in the back. Very discreet.” She squinted at the napkin, a conclusion dawning. “But that means that if you wanted to get into the dining room to kill Edgar, you’d only have two options. You could start in the back room and work your way forward, or you could go through the double doors from the hall. But you said the dining chairs had solid backs—really tall, solid backs. So if Edgar wanted to see who was coming through the double doors, he’d have to stand up. And if he stood up, either there would have been a struggle with the person who’d come to kill him, or he would have been killed from the front.” She paused. “But we know there was no struggle, because we know there was no mess to alert the police that anything untoward had happened. And we know he wasn’t killed from the front because he was facedown.”

“But he wasn’t killed from the back either,” Rachel pointed out. “I mean, he wasn’t struck from the back. There wasn’t a mark on him.”

“No, but even if the murderer just drowned him, they couldn’t have done it after coming in through the double doors, because Edgar would have had time to stand up and defend himself. And if someone’s risen and is facing you, you’re not going to be able to persuade him to sit back down, and then stand behind him and drown him, without disturbing anything. So the murderer must have come in through the butler’s pantry.”

“Because then Edgar could see them without standing up.”

“Yes.” Magda looked at the map again. “There wasn’t any rosé in the kitchen or dining room, right?”

Rachel was caught off guard by the change of subject, but she said, “No. A sweet white wine in the fridge, but no rosé.” Then, “Why?”

“Well, the fact that there was rosé on the table when he died and now there’s none in the house suggests that someone who liked rosé was eating there at the time, but now they don’t eat there anymore. And the fact that he didn’t stand up suggests he wasn’t surprised to see whomever he saw. And those together suggest the murderer wasn’t a random stranger, but rather a rosé drinker he knew.”

“Which means Mathilde or Elisabeth.”

Magda nodded, looking pleased with herself—as well she might, Rachel thought. Now, entry via the back door meant having a key, but presumably Elisabeth or Mathilde, or probably both, did have a key. So the vital question was, which one would Edgar have expected to appear at that door? Or at least, she added hastily, not been startled to see at that door?

“It was Elisabeth.”

Magda looked surprised. “Why her?”

“First, Mathilde would never enter a dining room via the butler’s pantry or a storage room in normal circumstances, so Edgar would have been surprised to see her. And second, even if she would, she couldn’t have entered through the storage room without any noise, because you’d have to move things to make a path. And she couldn’t have made the path before because someone who went into the storage room might notice.” When Magda didn’t respond, Rachel continued, “But Elisabeth must have come into the dining room via the butler’s pantry a thousand times. She said she was like family, so her entering through the back would be plausible. And she was there often enough to have made the path some other time without its seeming strange, since she was a sort of an odd-job girl. And I just realized something else I learned.” Out of air, she took a gasping breath and went on. “Whatever Elisabeth is after, she wants it badly. Either she pretended to be ill so she could sneak in unnoticed in the hope of finding it, or she came in even though she was ill in the hope of finding it. And she’s been in that bureau every day, presumably also looking for whatever it is. Whereas Mathilde has only come by irregularly.”

“Maybe Mathilde’s wily enough to be playing it cool.”

“If you’ve killed someone and now want to steal from them, you can’t risk playing it cool. And that’s the scenario we’re assuming, right?”

Rachel could see Magda considering possibilities, adding up evidence in her head. Finally she said, “What exactly was Elisabeth doing when you found her?”

It was Rachel’s turn to think. “She had her hands in a box of papers. And there were stacks that looked like she’d gone through already.”

“Personal papers or documents?”

Rachel cast her mind back. “Documents.”

“Did they look official?”

“Yes.”

“All right. So we know she was looking for something bureaucratic, something publicly or legally significant. And she got into the house unnoticed, which tells us she has a key, and it would seem a key to the back door, too.” Magda paused to add all this up. Then, “I’m not going to say she’s our only suspect, but you’re right, she’s our strongest suspect: someone who has access to the house and whom Edgar wouldn’t be surprised to see there; someone who’s done something involving him that she wants to cover up. And now”—she licked her lips—“now we have something on her. You caught her doing something she didn’t want to be caught doing. You know it and she knows it. So now you have an advantage. You can confront her and demand some answers.”

She was right. Rachel felt her heart lift. Then she felt it fall once more. “Not for a week.”

“Not for a—?” Then Magda too remembered. “Oh, right.”

They sat disconsolate. Rachel gazed grouchily into her half cup of cold chocolate. Shouldn’t it make a difference that she’d promised Alan before they had a lead, when it looked as if the whole investigation was going to end up going nowhere? It should, she answered herself, but it didn’t. A promise was a promise, especially to a spouse, especially after her recent behavior. Any other way was a step down a dangerous path. She heaved a sigh that out-sighed any sigh she’d ever heaved.

“It’s not so bad.” Magda said, mistaking the source of her dejection. “A week won’t change the fact that you did find her in suspicious circumstances. In fact,” she said, her tone growing crafty, “a long wait may wind her up to such a pitch of fear that when you confront her, she blurts everything out. Or she might be lulled into a false sense of security by five days of nothing.”

“Six,” Rachel corrected. “And she won’t be the only one lulled by it.” She bit her thumbnail, contemplating the yawning days ahead.