— 6 —

The Sacrifice of Nyiramachabelli

She became known in Rwanda as Nyiramachabelli. She told people, with pride and regret, what it meant: the old woman who lives alone in the mountains without a man. Dian Fossey was seldom completely alone in the Virunga mountains. From the start of her study she was accompanied by a Rwandan tracker and a cook; later her staff expanded, and Western students came to study with her. But alone and without a man named the sacrifice she made for her work with the gorillas: alone was how she felt in her struggle against poachers and in her battle with the community of Western scientists who, she felt, did not understand. Alone she struggled against poverty, against a staggeringly tough terrain, and against the conflicts of her raging desires.

The Virunga Volcanoes are corrugated, muddy, cold, dark. Sixty-seven inches of rain fall each year. It rains an average of two hours a day: a claustral curtain of cold gray water that shuts out even the memory of the sun. Every few weeks hail pounds with such ferocity that the eaves of the tin-roofed cabins are bent and twisted as if struck by hammers. This is the weather that precipitated attacks of what Dian called “astronaut blues”: uncontrollable crying, shaking, fever, sweating, claustrophobia. Several of her students, she said, suffered these symptoms and had to leave; one left camp after only four days.

Even on sunny days the slopes are difficult—slippery, wet, and tangled. Dian repeatedly broke bones in her falls. Wild celery and nettles grow over six feet tall; it is almost impossible to walk anywhere without cutting a trail with a machete, and every step is a side-heaving struggle up 45-degree slopes. Fields of nettles deliver a punishing sting that feels like electric needles even through two layers of clothing. Once a buffalo dragged Dian through a whole meadow of nettles when she mistook the surprised animal’s leg for a handhold as she wriggled through the undergrowth. On the lower slopes there are siafu, safari ants with mandibles so tenacious that when you try to pull them off, their heads stay in your flesh; they will bite through two layers of wool socks. And there are traps: wire nooses hidden among leaves or pit traps with sharpened stakes at the bottom or drop traps, piles of logs poised to fall at the touch of a trigger wire. Dian lived in the shadow of these traps, in constant fear for the animals she loved. Worse were the unseen bullets and arrows, which left no trace unless they found their mark.

Every scrap of food in Dian’s camp had to be carried up the mountain on someone’s head from the village of Kinigi or Ruhengeri. Food would keep two weeks at best; there was seldom any fresh meat or fresh vegetables or bread. She craved fat, sugar, salt; instead she had greasy tinned meat, frankfurters, beans, occasionally cheese—at very high cost—eggs laid by her pet chickens, and potatoes. At the end of the month potatoes were nearly all that was left to eat.

For most of the first two years of her study, Dian’s only human companions were her African employees, speaking a language she didn’t understand, born of a culture she did not share. Although Dian spoke some KiSwahili, she never mastered Kinyarwanda, the national language of Rwanda. On her first day at Karisoke she thought her cook was announcing plans to kill her; he had only asked if she wanted hot water. She was never fluent in French, a second language for many Rwandans; each word clanged dizzily in her skull, searching for its English equivalent. But the gap between her and her Rwandan trackers was wider than even language could fill. None of these people could remember with her the taste of a well-aged steak; none of them could recall the feel of crisp white bed sheets.

“I can tell you this,” Dian wrote to Ian Redmond, then a prospective student, in 1976, “the solitude, the lack of good food, the bloody weather etc. (paperwork, fatigue) has defeated fifteen out of eighteen students. The three that made it loved it because of the gift of being with the gorillas. . . . As far as I am concerned, the gorillas are the reward and one should never ask for more than their trust and confidence after each working day.”

When she returned to her cabin at the end of each day, Dian surrounded herself with images of the black furry faces of her friends, her reward: black-and-white photos of Digit, Macho, Kweli, Uncle Bert, Lee, and the others covered an entire wall.

Dian was a woman with large appetites, expensive tastes: Hermès dresses, fine restaurants, gold jewelry, the attentions of handsome men. On her first safari in Africa she brought along a mink stole to impress the other guests at her first stop, a fine Nairobi hotel. She wanted to be noticed, she wanted to be first. She loved being the center of attention at dinner with friends, keeping her listeners spellbound with stories and jokes. She loved dancing and cooking good meals for guests and dressing up.

In Louisville, where she worked as an occupational therapist for ten years, Dian had many boyfriends; she was informally engaged to Alexie Forrester when she left for her gorilla study. Once he came to her mountain cabin to “rescue” her. “If you stay here, you’ll be hacked to pieces,” he told her. “The Africans don’t want you here.” She sent him home.

In Kentucky Dian had loved the home she had made for herself in a rented farm cottage; in the fall she would run to the window on waking and be “blinded by the beauty.” She had loved the children she worked with at Korsair Children’s Hospital, and they had loved her. She was able to communicate with disabled children as could few others; she painted a Wizard of Oz mural on the wall of a drab examination room to cheer her patients, and she lured squirrels from the woods to delight them. Leaving behind the children, her home, her three dogs, and her friends, she wrote in her diary, “was the hardest thing I have ever done.”

She chose instead a life soaked with sweat and cold rain, a mountain world cloaked in mists, tangled with looming trees, slippery with mud. Her scientific career was forever overshadowed by famous predecessors; her love life became a string of impermanent affairs. Although she longed for wealth, a family, and children, she spent her nights alone in the little cabin in the Virungas.

By 1977, when students Amy Vedder and Bill Weber first met her in Chicago, Dian had been living in the mountains for ten years; she was forty-five. As they sat in a booth in the hotel restaurant, waiting for their dinner order to arrive, Dian began licking pats of butter off the cardboard backings and sucking sugar out of the paper packets.

On the Louisville stop of his speaking tour in 1966, Louis Leakey remembered Dian from their meeting at Olduvai. He had last seen her three years before, and her image had stayed with him: the tall, handsome, dark-haired woman leaving his camp with a bandaged ankle, prepared to stagger up the slopes of the Virunga Volcanoes to search for mountain gorillas. After his lecture she showed him the articles she had written for the Louisville Courier-Journal about her gorilla safari, and the photos she had taken of the huge, shy primates.

Louis offered to meet with her the following morning. He spent much of the hour praising Jane Goodall, then in her sixth year of study at Gombe. He spoke of Jane with the pride of a father; and now, Dian realized, he was welcoming her into his family of female protégées. She was to be his Number-Two Ape Girl—a position she first assumed with jealousy but later jealously guarded.

Before she embarked on her study, Louis arranged for Dian to retrace Jane Goodall’s footsteps almost literally: first a three-day stopover in England to visit with Vanne and Judy Goodall at their London flat, then a visit to Gombe to meet Jane and Hugo.

Once Dian arrived in Nairobi, Louis took her under his expansive wing. He helped her shop for a second-hand Land-Rover, which they named Lily. He ordered two tents for her, and when they arrived at the Coryndon Museum, he insisted on showing her just how a tent should be erected, putting up the larger one, on the museum lawn, in under four minutes, Dian recalled. Dian shopped for provisions, and Louis arranged for photographer Alan Root, whom Dian had met three years earlier on her African safari, to accompany her to the Congo to set up camp.

Root stayed with Dian at Kabara meadow for two days. He left on January 15, 1967, the day before her thirty-fifth birthday. In Gorillas in the Mist Dian wrote, “I clung on to my tent pole simply to avoid running after him.”

The vacuum of isolation stayed with her for several weeks. She could not bring herself to listen to the shortwave radio that Louis had insisted she bring, nor did she read any of the popular science books she had brought or even use her typewriter. “All of these connections with the outside world simply made me feel lonelier than ever,” she wrote. Hers was a purification by longing and loneliness, as she emptied herself into the abyss of the black African night. Once emptied by solitude, she would become a vessel, clean and spacious, and fill herself with the lives of the animals she had come to study.

George Schaller, a young Berlin-born zoologist, camped at 10,200 feet in the saddle between Mount Mikeno and Mount Karisimbi, in the area called Kabara, about twenty-five square miles of mainly Hagenia woodland, from August 1959 to September 1960.

Schaller began his study by trying to view the gorillas from the cover of a tree trunk, but the gorillas, whose eyesight he judged comparable to his own, usually detected him and fled. The other method was to approach within 150 feet of a group, in full view. Schaller found that after ten to fifteen prolonged contacts, some groups would allow him to approach within fifteen feet without being disturbed. In his more than three hundred encounters with gorillas—466 hours of observation—he identified 191 individuals. The members of six groups became completely habituated to his presence. Once a gorilla climbed into the tree in which he was sitting and stared at him with obvious curiosity.

In his scientific papers and his popular 1962 book, The Year of the Gorilla, Schaller challenged the image of gorillas as “King Kong monsters” and instead portrayed the huge, powerful apes as “amiable vegetarians” living in close-knit, cohesive family groups. He catalogued their facial expressions, vocalizations, and gestures; mapped their movements; and analyzed their diet. He recorded the care with which mothers groomed and carried their babies and the ferocity of the silverbacks performing their chest-beating displays; he noted each silverback’s idiosyncrasies, which colored the group’s character as well as determined its movements. His study was touted for its excellence and thoroughness.

In the same meadow where Schaller had worked, Dian established her camp. She hired the tracker, Sanwekwe, who had worked for Schaller seven years before. In six and a half months at Kabara she encountered three of the ten groups he had studied.

Her first attempts at observation were, by her own admission, amateurish and clumsy. While Alan Root was still with her, she began to follow a trail of knuckle prints in the moist black earth. After five minutes she realized that Alan was not behind her. She returned to the place where she had discovered the trail. He told her politely, “Dian, if you are ever going to contact gorillas, you must follow their tracks to where they are going rather than backtrack trails to where they’ve been.”

Although Dian began by approaching the gorillas silently and watching them from a hidden position, she later decided to announce her presence to the gorillas, hoping to calm them by imitating their sounds. As well as scratching, chewing, and making belchlike contentment vocalizations, she often greeted groups by pounding her chest—which Schaller had clearly described as a signal of aggression and challenge.

By July 1967 Dian felt she was on the verge of habituating the gorillas; after six and a half months of tracking and knuckle-walking toward each group, munching wild celery stalks to allay their fears and keeping her eyes averted, she was able to approach members of three groups, totaling fifty animals, within thirty feet.

But on the ninth day of that month her time at Kabara ended abruptly. European mercenaries serving the rebel leader Moise Tshombe had taken the regions of Kisangani and Bukavu; the entire eastern region of the Congo was under siege, and the border with Uganda had been sealed off. Soldiers streamed through village streets. Mail and telephone service were suspended, and all commercial air traffic was stopped. The park director sent soldiers up the mountain to order Dian to leave her research site.

Dian would later embroider the story of her escape from the besieged Congo with tales of incarceration, death threats, and rape. In Gorillas in the Mist she wrote that she was held captive, “earmarked” as sexual diversion for a soon-to-arrive Congolese general. She told Bob Campbell that she had been raped by Congolese soldiers. But affidavits she herself signed show that her one run-in with the Congolese military was a hassle over the expired registration for her Land-Rover. She was not raped, no guns were aimed at her, and she was never held captive; but her situation was terrifying, and her escape from the Congo—crossing closed borders in an unregistered car, made possible by quick-witted bribes—was a courageous achievement. That she invented other stories only shows that Dian did not consider her true ordeal harrowing enough.

Once she managed to reach Nairobi, she and Louis Leakey discussed plans for her future: he offered her a study of the lowland gorilla or beginning work on a long-term project on orangutans. But Dian was adamant: she wanted to continue studying the mountain gorillas. Within two weeks she was preparing to set up a new study site less than five miles from the Congolese border in the Rwandan portion of the Virunga Volcanoes.

Later Louis would write her that Nairobi was abuzz with criticism of him for having allowed her to resume the study—news he shared with unbridled conspiratorial pride. “If people like you and me and Jane and others, whose work takes them into strange places, put our personal safety first,” he wrote Dian, “we would never get any work done at all. . . . From my point of view, provided one took reasonable precautions, and did not deliberately run undue risks, work must go on.”

—————

“I don’t think many people understand how long it took Dian to habituate the gorillas,” says her friend Rosamond Carr. Rosamond was fifty-five when she met Dian. She and Alyette DeMunck, a Belgian neighbor ten years younger, helped Dian set up her new camp in the saddle between Mount Karisimbi and Mount Visoke. Sometimes they would accompany Dian up the mountain and follow the gorillas’ trails with her. Often they heard the gorillas pokking their chests in defiance or hooting to distant groups but, remembers Rosamond, “we never saw gorillas at all.”

In her first months at Karisoke Dian, even alone, saw little of the gorillas; an hour here, then weeks without a glimpse. Unlike the gorillas of Kabara, who had known George Schaller, the mountain gorillas of Rwanda knew man only as poacher, commander of vicious dogs, and shooter of arrows and bullets. So it was with great restraint and humility that Dian tried to ease gently into the shy animals’ lives.

She did not want to surprise them; at first she tried to stay hidden. Then she began to approach gingerly, gently, on hands and knees, slapping and belching a greeting as soon as she was within earshot of a crunching, belch-mumbling group. Occasionally she would climb a tree, not only to see them, but to honor the etiquette of the relationship she was nurturing: “It was important,” she wrote in her thesis, “that the group, especially the silverback, knew the location of the observer.” As Jane had done on the Peak at Gombe, Dian offered her promise: I am here. I am harmless. I wait.

She would knuckle-walk to within a hundred feet of them, then eighty feet, then fifty, then thirty. Scratching herself and crunching the bitter wild celery, she would settle down in the foliage, kneeling, sitting, or reclining, harmless and calm. I am here she announced with a belch vocalization. I am harmless she promised with her posture. But further, crunching celery and scratching herself, she told them I am one of you.

For two years she refused to follow the animals past the contact point, “to prevent them from feeling subject to pursuit,” as she later wrote in her thesis. Like Jane Goodall, Dian began by offering her presence to the study animals, not imposing it. But Dian was determined that her study, unlike Jane’s, would remain “pure.” She was well aware of the criticism leveled at Jane for setting up a feeding station for the chimpanzees; it was said that she was altering their natural behavior.

Dian knew she could not have lured the gorillas with food even if she had wanted to: their world is covered with food, so abundant that they sleep on it, walk on it. The danger was that she would disturb them with pursuit or too-close contact. She did not want her intrusion to shatter the tranquility of the family groups, so calm, so perfect.

So when National Geographic photographer Bob Campbell arrived at Karisoke in August 1968, nearly a year after she had founded the camp, he found little to film. “The gorillas were very wild and unhabituated at that stage. I had a big problem for eighteen months,” he remembers. “She tied me down to her standard methods of observation. She wouldn’t have me harassing the animals or doing things to make them react; just go out, find them, sit in a good observation spot and then watch what they do. I wasn’t to follow them around.

“Sitting thirty to fifty feet away, it’s impossible to even see the whole group. It was obvious I wouldn’t get what I wanted, sitting back and waiting for them to expose themselves.”

It was equally obvious to Bob that at first Dian didn’t want him there. The thought of his frightening the gorillas horrified her. But she was also afraid of his judgment: Dian, at six feet, looked powerful and imposing, but she was struggling up the steep slopes; her asthma made her stop frequently, gasping for breath, and she often slipped and fell. Bob often had to stop and wait for her.

“She was unhappy that a strange person could see how much difficulty she had operating on those mountains,” he remembers. “She wasn’t prepared to have someone unknown to her witness just how difficult things were with her.”

For Bob the work was frustrating. After a year and a half of work, as he remembers it, he had only two scenes of Dian near enough to the gorillas—within ten feet—to be taken in by the movie camera lens. National Geographic by then had film of Jane handing chimpanzees bananas, grooming their fur, playing with their babies. They wanted more from Dian.

At one point, attempting to film Dian with the gorillas, Bob sent her in pursuit of Group 8, which was feeding up beyond a ridge. He suggested Dian approach them from below, giving him a clear view without foliage in the way. She was within forty feet of them when suddenly the silverback of the group—an animal she had named Rafiki, the KiSwahili word for “friend”—charged at her.

“That caused a mob situation,” Bob recalls. “The whole lot came down—five gorillas screaming at short distance, pouring out of the foliage down the steep side of the ravine, screaming.” The charges and screams continued for half an hour. Dian sat with her back to them, crouching, pretending to feed. She couldn’t tell where they were. “The screams were so deafening I could not locate the source of the noise,” she later wrote in an article for Omni magazine. Again and again they charged and screamed, hair on end, canines flashing, releasing a gagging fear odor. Suddenly these were the gorillas described by the nineteenth-century explorer Paul Belloni du Chaillu: as “monstrous as a nightmare dream. . . . So impossible a piece of hideousness, . . . no description can exceed the horror of its appearance, the ferocity of its attack, or the impish malignancy of its nature: savage, enormous, hirsute, aggressive, cunning, a predatory beast of violent passions.”

When at last the gorillas moved away, Bob ran to Dian, horrified by her ordeal. She wasn’t shivering or crying, and she wasn’t injured. She was angry at him: it had been his idea for her to sneak up on them from below. And she was deeply hurt. “She was emotionally hurt,” he said, “that this formerly friendly group could suddenly charge like that, that they could suddenly switch and become these frightening creatures.” She felt that somehow she had failed them; their trust in her had been shattered like a pane of glass.

Bob returned to Karisoke for more film footage on and off for the following two years. He gradually won Dian’s trust. He would help her cut Batwa poachers’ traps and herd away wandering Batutsi cattle. He thoroughly documented the last days of Dian’s caring for Coco and Pucker, the two pathetically ill juvenile gorillas captured by poachers for the Cologne Zoo. He helped Dian conduct her census work, often camping with her and Alyette in small tents, carrying all their food and water on their backs. He helped her train her Rwandan staff in tracking skills, fixed broken lanterns and stoves, constructed new cabins from tin sheeting she would then paint green.

But his time was running out. So, he says, it was his photography needs that finally induced Dian to move in among the gorillas.

At his garden-bordered home on the outskirts of Nairobi, Bob Campbell sat in an easy chair, the tea service beside him, as he told me his story. He was still a handsome man, slender, elegant, soft-voiced. Eyeglasses correct the imbalance in his eye muscles caused by years of looking through a camera lens with one eye and at the object being filmed with the other. “We came to an agreement. I would try my methods, and she would stick to hers. So I started crawling around. I was getting in among them. I got to the state they would come and touch me. As soon as that started to happen, I wanted to get Dian in there so they would do it before my camera.

“It took her a while to break down her resistance to pushing the gorillas. She didn’t want to intrude too much,” he remembered. Shy as a new bride, Dian would keep her eyes averted, her body low, her voice soft. And then she would lie down before them, vulnerable, still. It was while she was lying prone in the foliage that Peanuts, of Group 8, first came forward to touch his fingers to hers.

“She was at first a little uncertain,” Bob remembers. “At first she was trying too hard to be just an observer. And then she had the animals touch her.” Bob paused. “It was almost overwhelming for her.”

In January 1970 Dian found herself again following in Jane’s footsteps, as the second of Louis’s amateur protégées to enter Cambridge in pursuit of academic credentials.

Like Jane, Dian did not have a master’s degree to begin with, although she did have a degree in occupational therapy from San Jose State College. Louis had arranged for her, too, to bypass the degree that students were ordinarily required to have before beginning a doctoral dissertation. And, like Jane before her, Dian hated Cambridge. “I hate it here because it isn’t Africa,” she wrote to Louis during her first semester there. “I feel like a mole.” But she realized the necessity for a Ph.D.—her “union card,” as she called it, for getting further grants.

Dian did not enter Cambridge with the same flourish as Jane had, for her initial discoveries were not nearly as stunning. When the termites had first begun to swarm at Karisoke, Dian had hoped that she would see, as Jane had, the apes using grass stems and twigs to get at the juicy insects inside; she was disappointed to find no evidence that gorillas use tools. Neither had she any evidence that they hunted; they ate mainly leaves, stems, bark, fungus, earth, snails, and grubs that they dug from rotting bark with their great hands.

Yet Robert Hinde, who had supervised Jane, told Dian he was impressed with her data—hundreds of pages of longhand descriptions of her days, trail signs, vocalizations and, when the gorillas were visible, the actions of every member of the group, the time they spent eating and resting, maps of their range. She had developed a novel way of recognizing individuals: each animal’s nose had a different configuration of ridges, as individual as a fingerprint.

Like Jane, Dian named her study subjects; but this was 1970, and even the venerable Schaller named the gorillas he studied. The idea was less outrageous by then, if still not totally acceptable. (As late as 1981 the anthropologist Colin Turnbull refused to reward the galleys of Gorillas in the Mist with a favorable blurb; the reason he gave was that he didn’t like the fact that the animals were named.)

In this second of Louis Leakey’s protégées, Robert Hinde may have hoped for a more malleable convert to the “new ethology” of statistics, measurement, and maps. He got on well with Dian and often visited her at her flat. She called him Robert and listened carefully to what he said. At one point, she wrote her friends the Schwartzels that she had learned to enjoy searching through her data and writing up scientifically. With jealous pride she added, obviously echoing the words of her adviser: “This is something that Jane Goodall never learned to do.”

But Dian failed to learn the most important rule of male-dominated empirical science: the rule of separation, of distance from her study subjects, of the wall thrown up between observer and observed.

“If she ever planned to be solely a detached, dispassionate academic observer,” National Geographic’s William Grosvenor said of Dian, “that plan was soon abandoned.”

Digit from Group 4 would come forward to play with her hair, hang on her head, and playfully whack her with foliage. Puck, a youngster in Group 5 who especially enjoyed playing with Dian’s camera gear, would come over “to sit down and ‘chat.’ ” Dian wrote the Schwartzels:

He comes right up to my side, plops down and, looking me directly in the eyes, begins very seriously a long tirade of relating past events, (?), injustices by his family, (?) how the weather has been treating them (?), and on it goes. All done in soft drones and hums, sometimes with mouth opening and closing as though he were trying to imitate human conversation.

Once an adult female in Group 4, Macho—KiSwahili for “eyes”—split off from her group, which had moved away to feed, to return to Dian and gaze into her eyes. “On perceiving the softness, tranquility and trust conveyed by Macho’s eyes,” Dian wrote, “I was overwhelmed by the extraordinary depth of our rapport. The poignancy of her gift will never diminish.”

Dian wrote to her mentor, “It really is something, Louis, after all these years, and I just about burst open with happiness every time I get within 1 or 2 feet of them.”

———

At Cambridge, as at other academic institutions, ethology students have a term that encapsulates their most dreaded enemy: the “dirty data stealer.” These are people, other students, competitors, who steal your data and use it in their own thesis or paper without giving credit. For this reason many academic researchers keep their file cabinets locked. The fear of theft fosters a paranoia, a possessiveness, unlike that found in almost any other setting.

The ivory towers of academia are rife with petty rivalries, snubs, jealousies, and gossip. Jane Goodall, even after she earned her Ph.D., was still a subject of constant comment at Cambridge: one student who had attended a symposium at which Jane was scheduled to speak wrote that the participants positively dripped with sympathy and concern when they learned that Jane’s appearance was canceled by an attack of malaria, “but later privately wondered why she always conveniently suffered these malaria attacks before important speaking engagements abroad.” Dian’s friend and Cambridge colleague, Richard Wrangham, once wrote her in dismay that no one was speaking to him because his new ideas about social organization in monkeys were unpopular.

For Dian the world “outside,” away from her gorilla families, loomed monstrous with inflated egos. At the Leakey Foundation, which along with National Geographic was supporting her work, organizers worried endlessly over the seating arrangements for their functions—for as cofounder Tita Caldwell explained, “People would get really ugly about where they would be seated. They would actually say to me, if I don’t get to sit next to Jane Goodall, I’m not going to give you any more money.” Often people who gave money to foundations like these were fickle, fawning, false, petty, and power-hungry: many of the trustees used the foundation as a social ladder. “I’d never encountered such tremendous jealousy and resentment,” Tita remembers.

When Dian went to the gorillas of Karisoke, she would sometimes sing to them. Not in the human sense of singing; she would sing a gorilla song.

Ian Redmond has heard gorillas singing among themselves. It sounds, he says, “like a cross between a dog whining and someone singing in the bath.” The animals will do this when they are exceptionally happy, usually on sunny days when they are feeding on something particularly delicious like juicy bamboo shoots or rotting wood. Ian tasted the wood the gorillas eat; it tasted “like old wood.” But to the gorillas, old wood seemed to have the effect that chocolate does on some human beings. It was a food of good feelings. Feeding in a family group, basking in the sunshine, enjoying a feast of this favorite food, “they are so filled with good feeling that they just have to communicate this,” Ian said. Sometimes they throw their arms around each other while they are singing and chomping: a celebration of eating, of the rare warm sun on black fur, of belonging. And sitting among them, Dian would be engulfed by their happiness, and she, too, would begin to sing—a choir of voices, the gorilla song of good feeling, of togetherness, of inclusion.

When Dian was with the gorillas, she was as one of them. But when she returned to her cabin alone at night, she was once again Nyiramachabelli: the old woman who lives alone in the forest without a man.

Dian refused to use check sheets, a standard tool in ethology, to record the behavior of the gorilla groups. A typical check sheet will have column headings for behaviors—grooming, feeding, playing, traveling, resting, for instance—that can be ticked off when observed, as a manager would check off merchandise in a warehouse.

Nor did Dian take her notes on a “sampling schedule,” which is usually used in conjunction with check sheets. With a sampling schedule behavior is recorded only at precise intervals—once a minute, clocked by the stopwatch, for example—to assure that the researcher is getting a true “sample” of what the animals are doing.

These methods are useful for organizing percentages—for instance, you can infer from these data that an animal spends, say, 40 percent of its time feeding. But Dian felt that the character and depth of the gorillas’ lives could not be accurately portrayed with such mechanistic methods. She did not want to merely “sample” their lives; she wanted to experience them, with all of the associations, feelings, sounds, and images that entails. The normal group life of a gorilla family, except for raids from rival silver-backs or voluntary transfers of females to new groups, is a seamless continuum of attachments; Dian refused to separate them into columns on a check sheet or seconds on a stopwatch. She would portray their lives like a story, whole.

Bob Campbell remembers the conflict that arose between Dian and her thesis adviser: “She told me Hinde was a bit hard on her. He wanted her to take her data in a rigid and scientific manner, and she wanted it to be free-flowing. He wanted numbers. She wanted words.”

Dian knew this was not the sort of information revered by science. “Ah, [Sandy] Harcourt—now there’s a good scientist. He knows how to do thus-and-so,” Amy Vedder remembers Dian saying to her, “not like me.”

Amy, an American student who went to Karisoke to work with Dian in 1978, had been schooled in sampling and recording technique while earning her B.A. in biology with honors at Swarthmore College. She remembers that working with Dian was frustrating: Dian did not play by the scientific rules. “We were supposed to record behavior of all individuals—but you can’t write down or see all of what happens to all animals all the time. It’s simply impossible. We were supposed to note vocalization, but she never edited tapes to use as learning tools to standardize the names of the vocalizations. We were supposed to note nursing, but not the number of seconds, or right or left breast. What she was looking for was not clear.”

It was an assessment with which Robert Hinde apparently agreed. Dian’s relationship with her supervisor deteriorated so far that in December 1975 she threatened, in two angry cables, to resign from her thesis. And in 1976 she described to Richard Wrangham, whose office in Cambridge was next to hers, how her furious supervisor had harangued her for hours the night before her oral examination:

In comes the professor screaming his head off about my lack of gratitude. . . . He talked and raved for about 3 hours. . . . On and on it went until I asked him to leave. I couldn’t count the number of times he said “after all I’ve done for you . . .” and that I was exactly like Jane and would fail just like he knew she would. . . . It was as though he had had all of this stored up in him against Jane and was using me for an outlet since he would never dare rant and rave in such a manner to her.

Dian felt she was forever living in Jane’s shadow. When she began to write her popular book, she joked with friends that she would title it “In the Shadow of In the Shadow of Man.”

She was jealous of Jane from the start. When she first met her at Gombe, she wrote to friends in the States about the visit. She chose to highlight an incident in which she had predicted chimpanzee behavior that Jane had not foreseen. Dian worried that the chimps would be frightened by a leopard-print travel bag she had brought. Jane told her the chimps would not notice it. But, true to Dian’s prediction, a canny female chimp spotted the bag, screamed, and fled.

Jane, it seemed to Dian, had it all: marriage, a child, fame, and funding. Although Louis had arranged for the same institutions to fund Dian’s work that had supported Jane—the Wilkie Brothers Foundation, the National Geographic Society, the Leakey Foundation, and others—the money never seemed to stretch far enough for Dian. At one point she was financing boots and raingear for her staff by charging them on a K-Mart credit card borrowed from a friend. Dian was able to pay for much of her medical and dental care only by going to friends, or friends of friends, who would charge her less.

Neither Dian nor her gorillas seemed able to compete successfully with Jane and her chimps for the limelight. Dian made important discoveries about gorilla life: how females transfer, either voluntarily or via raids from rival silverbacks, out of their natal groups; how a raiding silverback will sometimes kill the infants of a mother he is kidnapping to bring her into heat so he can mate with her; how gorillas will sometimes eat their own dung to recycle nutrients. But these discoveries were outshone by Jane’s findings about chimpanzee hunting and tool use, cannibalism and warfare—behavioral aspects that made the chimps seem more like people.

On at least one occasion Jane and Dian were nominated for the same conservation prize; Jane won it. Once Dian complained to an editor at National Geographic, Mary Smith, “If I had blond hair”— (“meaning Jane of course,” Smith adds)—“things would be a lot easier for me.”

Years later, though, Dian accepted her place in the hierarchy of Louis Leakey’s “three primates.” After Biruté Galdikas became the third “ape woman,” completing the trio, Dian vigorously defended her place as second.

The three were scheduled to speak at a symposium at UCLA. Joan Travis, one of the founders of the sponsoring Leakey Foundation, gave a party and made the mistake of asking Biruté to introduce Jane at the next day’s symposium. When Dian discovered that Biruté—number three—had been given that honor, “Dian went into a tantrum,” remembers Tita Caldwell, who watched the scene in dismay. “It was a nightmare, like a bad movie, like a high school drama. [Biruté and Dian] were shouting in each other’s faces, a real gutter fight.

“Dian stalked out and came back with a phone book in her hand. People were drifting into the living room, unaware of what was going on, and people asked, ‘Dian, what are you doing?’ From her great height—she was six feet tall and she was standing about three steps up the stairs—she announce ‘I’m looking for a taxi. I won’t stay in this house another minute.’ ”

Biruté remembers: “People had been telling me all kinds of things about Dian, but I didn’t see them—she’d always been so kind to me. And then one day she just became hysterical. She just went insane. I’d never seen a human being like that—she just blew up! And poor Jane was caught in the middle, and Jane tried to sort of intercede. It was like sibling rivalry or something—it made absolutely no sense.

“Dian took it most seriously of all—she was number two so she deferred to Jane, and she expected that kind of deferment from me. I didn’t understand the depth to which she expected this. [She was] hurt by the lack of deferment on even the smallest issue.”

For the solitary orangutans Biruté was studying, hierarchy has little meaning. For the large community of chimpanzees of Gombe, who travel in constantly changing smaller groups, social rank is of limited importance. But for a close-knit family of gorillas, one’s place in the group is all-important. And so it was for Dian. “I didn’t realize at that time,” said Biruté, “that Dian was a gorilla.”

Dian’s thesis, “The Behavior of the Mountain Gorilla,” is a very technical, dry document, full of maps and charts and graphs. But it is clear that to Dian the gorillas are not numbers to be calculated, their lives not data to be manipulated; they are thinking, feeling individuals, deserving consideration in man’s as well as God’s moral realm. She begins her thesis with an admonition for the scientists to whom the thesis is addresse “Love the animals,” Dian quotes from Dostoevsky. “God has given them the rudiments of thought and joy untroubled. Don’t trouble it, don’t harass them, don’t deprive them of their happiness, don’t work against God’s intent.”

The thesis was accepted, and her Ph.D. awarded in 1976. But for Dian it was a somewhat hollow victory. Her careful mapping of vegetation zones and gorilla ranges, her catalogues of food plants and dung parasites, her careful analysis of age classes and maternal behavior and female transfer—all this did nothing to protect the gorillas. She began to dismiss such data with a sniff as “theoretical conservation.” Science, she was convinced, would not save the mountain gorilla. The animals were disappearing, not for lack of data but because they were being murdered. Increasingly, she forsook data collection for what she called “active conservation.”

In the spring of 1977 the poaching situation at Karisoke reached a crisis point. In March Ian Redmond and a tracker, Nemeye, found the naked footprints of Batwa poachers on the trail of Group 5; the area was infested with recently set traps. In one day they found and destroyed twenty-one snares and three poachers’ shelters. A month later they searched the remote northwestern portion of the study area, where Group 5 was then roaming: the men found and destroyed thirty-five traps in two days.

Dian feared for the gorillas’ lives as never before. “We can’t find all the traps,” she wrote in her diary. “Sooner or later one of them is going to get caught.”

So she made a decision that sickened her: the gorillas of Group 5, animals she had spent years shyly approaching, animals she had dared not even follow until she had known them for two years, would have to be forced to leave the trap-laden portion of the study area. They would have to be herded to a new area, like cattle.

Dian directed her men to do the job. She knew she couldn’t bear it: the gorillas’ terror before the din of her staff ringing poachers’ dog bells, the air rank with the stench of their fear, their trail covered with watery dung. “I stay in and make sure I won’t hear anything,” she wrote in her diary. “It is HORRID but it must be done.”

But only days after this drastic effort, six poachers set their dogs on a different group of gorillas—a fringe group known to Dian from previous censuses. Enraged, Dian and her camp staff set out the following morning to try to capture the poachers. In the hail and bitter cold, Dian’s lungs and legs could not keep pace with her fury; her heart pounded; she fell repeatedly. She turned back. The men, continuing on, found only a handful of traps.

Word went out to the park guards: Dian would reward them for any poachers they captured. One bright morning five park guards appeared at her camp with Munyarukiko, the leading Batwa poacher in the Virungas. They paraded him in front of her. He stood, eyes downcast, as she glared at him. Ian remembers: “It was not a pretty sight. I can honestly say that the look in Dian’s eyes was hatred, and I hadn’t seen hatred like that before.”

Dian opened bottles of Primus beer for all the men to celebrate. She gently dressed a graze on a guard’s shin. Joyfully she paid the guards the equivalent of $120. They assured her that they would turn Munyarukiko in to the park conservator in Ruhengeri.

Minutes later her woodman asked her why she let them leave. Didn’t she know that the guards had met the poacher by prearrangement at a village bar? Didn’t she know they were now splitting her reward money with him?

The next day she drove to the Batwa village where Munyarukiko lived to capture him herself. He had fled, leaving his five wives and children behind. In a rage she searched his hut, trying to find his gun. It was gone. She tore down the matting from the walls inside the hut, dragged it outside, and set it afire. She demanded that the wives give her the gun and grabbed one of his children, a four-year-old boy, threatening to hurt him if they didn’t obey. The women fled, leaving the boy with Dian.

“I know the details of this because I was the boy’s baby sitter for a couple of days,” said Ian. “The kid was living happily in my cabin, eating and playing with toys he was given, becoming completely at home.”

The boy cried when he learned he had to leave the next day. Munyarukiko had obtained a legal judgment against Dian. While her men’s boots rotted from the wet, while her camp lanterns sputtered and died, while her patrols lacked raingear and meat, while she subsisted mainly on potatoes, Dian was assessed a fine of $600.

“Dian,” remembers Bill Weber, “was an incredible, incurable romantic. What we saw was what was left of this person who had believed, ‘This is great, this person is incredible, this is true love’—and had been disappointed every time.”

Dian approached almost every new human friendship with great enthusiasm. Bob Campbell remembers how at first she trusted her African staff so completely that once, when she had just cashed a grant check, she proudly showed the men a huge handful of franc notes and exclaimed, “Look at all this money!” Within a week the money had been stolen. Dian would write enthusiastically to friends about many of the new students who arrived in camp: “This is a person of integrity,” she would write confidently and would shower her new helper with extravagant evidence of her affection; Craig Scholley, an American, remembers that while he was a student at Karisoke, Dian threw a birthday party for him in her cabin, a beautiful meal laid out on an ornate African cloth. “I said, ‘That’s a beautiful tablecloth. Where did you get that?’ And she immediately took it off the table and handed it to me and said, ‘This is yours.’ ”

But one by one each student slipped from her favor. Dian trusted too much, expected too much: like the women asked to write stories about trapeze artists in psychologists Pollock and Gilligan’s study, she imagined a safety net that wasn’t there.

Dian’s love affairs always ended sadly. Bob Campbell went back to his wife in 1973. Her subsequent love affairs—almost always with other women’s husbands or men otherwise attached—always left her lonely. She subsisted for months on great crates of pornography she had friends ship to her, and she kept a vibrator to satisfy her large appetite for sex. Dian was like a silverback who raided other families for mates. But she could not hold on to them; these affairs, born of deception of another woman, always ended when the men began to lie to Dian instead.

“Dian had been shat upon by a lot of people,” Ian Redmond says. “Therefore she was very wary about entering into a relationship. She had been hurt.

“But the gorillas were straight. They were honest in their feelings toward her. If they were angry, you could see they were angry; if they liked you, they showed it. It was very up front. Dian appreciated the honesty of the relationship you have with gorillas, and you don’t owe them anything and they don’t owe you anything, other than trust. With the gorillas she didn’t have to hide her feelings from them. She had a very honest relationship with them.”

————

On the last day of 1977, Digit was killed. Serving as the sentry of Group 4, he sustained five spear wounds, held off six poachers and their dogs, and even managed to kill one of the poachers’ dogs before dying. Ian found his handless, decapitated body on January 2.

“I cannot allow myself to think of his anguish, his pain, and the total comprehension he suffered of knowing what humans were doing to him,” Dian wrote in “His Name Was Digit,” a tribute to her friend.

She photographed the body and had a doctor from Ruhengeri come up to perform an autopsy. On the day of the autopsy her woodman, working only fifty feet from her cabin, began to yell, “Poacher!”

“When they brought him out of the forest onto the meadow, I could see he was one of the Twa from what is basically a poacher village near the park boundary,” Dian wrote. “I saw something else as well which froze my blood and nearly caused me to lose all sense of reason. Both the front and the back of his tattered yellow shirt were sprayed with fountains of dried blood, far more than could result from an antelope killing.”

“I can’t tell you,” she wrote in many letters, to friends, colleagues, and lawyers, “how difficult it was for me not to kill him.”

The captive admitted to having been one of Digit’s killers. He also provided the names of the other five, one of whom was Munyarukiko. It was his dog that Digit had killed.

Dian debated whether to publicize Digit’s death. She knew that a public outcry could bring large sums of conservation money to Rwanda, but she feared the money would only line officials’ pockets. Finally, however, keeping Digit’s death quiet seemed too horrible: “I did not want Digit to have died in vain,” she said. A few days later Walter Cronkite reported Digit’s death on the CBS Evening News.

Later Dian resumed her contacts with Group 4. But, she wrote in her book, “for countless weeks unable to accept the finality of Digit’s death, I found myself looking toward the periphery of the group for the courageous young silverback. The gorillas allowed me to share their proximity as before. This was a privilege that I felt I no longer deserved.”

In many ways Karisoke Research Center belied its name. By the time Dian began to host students regularly, as her study neared its second decade, research was clearly secondary on her agenda. She did not accept the notion that humans were by rights more important than gorillas; she did not obey the hierarchy of rules that placed science above love. “She was prepared to put all the [research] money into antipoaching and forget about her research work, as long as the gorillas survived,” remembers Bob Campbell.

Students were allowed to gather data, but if they were to work with her, at her home, they would also have to take on antipoaching patrols. These were being paid for by the Digit Fund, which Dian had incorporated in June 1978. Peace Corps volunteers assigned to her camp were asked to carry guns—a request that many refused. They were asked to track down poachers and bring them back to Dian as captives. Karisoke Research Center had become an armed camp.

Unlike Jane’s research center at Gombe, with its spacious communal dining hall where students gathered for dinner each night, Karisoke students remember no feeling of community. There was no central gathering place at this center. Dian provided no dining hall, lecture area, or library; there was no place where researchers, students, and Peace Corps volunteers could regularly congregate, not even a common campfire.

The students and volunteers who worked at the camp—at most half a dozen at a time—ate separately, cooking their own meals in the little tin cabins. Dian communicated with them mainly on slips of typewritten scrap paper, delivered cabin to cabin by her African staff. To save typewriter ribbon, Dian would use both the red and the black portions. Among some students the idea arose that her “red notes” were the angry ones, but it turned out that her tone was not predictable from the color.

Dian organized her camp in this manner purposely. When, nearly two years into her study, in 1968, she had resigned herself to the need for student help on a census of the gorilla population, she had written to Louis Leakey asking that the volunteers he chose be willing to pitch their tents a ten-minute walk from her camp; she did not want to spend her evenings talking with people or cooking for them.

She had always been ambivalent about sharing Karisoke and the gorillas with other researchers. Though she was ravenous for human company, she demanded a silverback’s control. To work with animals she loved like family, to protect them from unwanted intrusion, to defend them against poachers, Dian expected from her students absolute loyalty, absolute respect, absolute integrity. No human could fulfill all her requirements.

Dian’s unpredictable temper was legendary. “If things were generally going badly, anyone could get in the line of fire and be the brunt of her outbursts,” said Ian Redmond. Although Ian was one of the few students Dian lauded in her book, she threatened on numerous occasions to throw him out of camp, primarily for sleeping late and for turning in his weekly reports late. “She could be talking to you and then turn and just glare, and then put on this great display, and then turn back to you and talk normally. And I think,” Ian muses, “that this was something she developed, possibly, from the gorillas putting on a bluff display, not unlike a silverback.”

Dian, by the time students began to arrive, was in nearly constant pain: she suffered from emphysema, sciatica, a bad hip, calcium deficiency, and insomnia. She drank often. Though she directed the antipoaching patrols, she seldom accompanied them. She spent most of her time in her cabin and seemed to resent the intrusion of a student knocking at her door. After Digit’s death, students remember that if they knocked, Dian would fling open the door and demand, “Who’s dead now?”

Students constantly heard the clatter of her typewriter. She was writing letters. She wrote long, loving letters to the Schwartzels, brimming with concern for and interest in every aspect of the family’s life; she answered, personally and promptly, every letter ever written to her by a schoolchild; she kept in touch with Ian Redmond’s mother, a widow whose isolation she thought mirrored her own. Even though holed up in her cabin, cutting herself off from her students and staff, Dian was desperately seeking connection.

Few of the volunteers and students who came to Karisoke lasted more than a few months; several left after only days. Before they left the States to work at Karisoke, Amy Vedder and Bill Weber talked to former students who had worked with Dian: “We were warned twice. They said, she drives away everyone who works with her,” the couple remembers. And in spite of herself Dian knew she did this. Ann Pierce, an American primatology student who had worked at Gombe, did some work at Karisoke while Dian was overseas. Ann remembers Dian saying to her, “I’d love it if you could come and work with me at Karisoke. But you’d end up hating me.”

“Oh God,” Dian would write in her diary, on nights when her camp was full of people, “I feel so alone, it hurts like physical pain.”

On July 24, 1978, student David Watts encountered wet dung (a nervous reaction) on the trail left by Group 4. Minutes later he found the still-warm body, decapitated, of Uncle Bert, the silverback leader of the group, whom Dian had named for her uncle. A bullet had pierced his heart, and a panga wound stretched fifteen inches along the left side of his chest.

Two days later Bill Weber found Macho’s body, face down. A single bullet had pierced the left side of her chest. Her three-year-old son, Kweli, was wounded in the right upper arm. He died that October of gangrenous infection. Soon the growing graveyard of poachers’ victims would also receive the body of another baby. Lee, a four-year-old female of Nunkie’s Group, which Dian had first met in 1972, had broken free from a poacher’s trap, but the snare remained around her left foot. For three months the wire worked deeper and deeper into her flesh. She, too, died a lingering death from gangrene.

On Christmas Day, 1978, Amy Vedder knocked on Dian’s cabin door. Amy knew Dian was suffering, and she knew how physic ally difficult it was for her to hike out to see the gorillas she loved. But Amy had just spent the morning with Group 5, and they were unusually near camp. The weather was sparkling clear and fine. “Group 5 has a Christmas present for you,” Amy told her. Dian looked at the student quizzically. “They’re only ten minutes away,” Amy said.

But Dian’s heart had slammed shut. “No,” she told Amy. “No.” And she closed her cabin door.

News of open warfare at Karisoke began to reach the American and European conservation community. Dian, it was said, was running a police state, not a research camp. Her antipoaching patrols were invading Batwa villages and taking captives. Ian was speared in the wrist, a nerve permanently severed. One of Dian’s trackers, Semitoa, suffered a broken nose and brain concussion when he leaped a chasm to escape from an ambush by poachers.

Conservation money earmarked for gorilla protection was now pouring in from various agencies, but the money did not go to Dian. The bylaws of organizations such as the British Fauna Preservation Society and the African Wildlife Leadership Foundation dictated that funds must be channeled through the governments of the countries involved. Much of the money generated by the publicity about gorilla deaths ended up financing new park vehicles, new roads, and a new gorilla tourism program. Dian called these funds “Digit’s blood money.”

Stories and rumors flew: Dian shooting at tourists, Dian torturing poachers, Dian wandering about drunk with a gun. Dian, it was said, was clinically insane.

Beryl Kendall, a primatologist studying pottos in the remote rain forest of Uganda, remembers that the rumors reached her even there. “They were unbelievable, incredibly vicious rumors,” she said. “The international research community totally cut Dian off.”

With Louis Leakey dead, the foundation bearing his name now cut itself off from his second protégée’s project. Dian was too great a threat to public relations: even while giving a lecture she was often rude to the audience, cutting off questions by telling people to shut up and sit down.

And in February 1979 Dian received this cable from her most important funding source, National Geographic: RECEIVED SERIOUSLY DISTURBING REPORTS CONCERNING EVENTS YOUR CAMP STOP SUCH ENCOUNTERS CREATE CONCERN AND EMBARRASSMENT NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC.

Days later, U.S. Secretary of State Cyrus Vance telexed the ambassador to Rwanda, Frank Creigler: NG RESEARCH COMMITTEE BELIEVE IT NECESSARY THAT DR FOSSEY LEAVE RWANDA FOR A WHILE. THIS WOULD HELP DEFUSE LOCAL TENSIONS.

Dian conceded defeat. She wrote, “Have finally realized I can no longer live here. The beauty of the late sun at 5 going down behind the trees that Uncle Bert, Macho, Kweli should be enjoying—what they loved so much. No longer does it hold any beauty for me. It holds only hurt.”

On March 4, 1980, Dian arrived in Ithaca, New York, to begin a teaching stint at Cornell and to finish Gorillas in the Mist. She would attend to her health, including having a major operation on her back. She would give lectures with Jane Goodall and Biruté Galdikas. She would gather her strength: through her book and through her lectures, she vowed, she would appeal to the American public to care about the gorillas, to help.

During this time Dian’s heart began to heal. She wrote warm letters to Kelly Stewart, once a favorite student, from whom she had become estranged. She became good friends with Jane Goodall, and the two exchanged letters. To Tita Caldwell, Dian wrote of Jane’s admirable patience, dignity and graciousness. Dian patched up her argument with Biruté Galdikas, who still keeps the last letter Dian wrote to her, in pencil on looseleaf, dated April 1981:

I remain tremendously proud of you; . . . you are deeply appreciated, respected and even loved. The depth of your integrity, sincerity and feeling not only [for] your animals but humans as well, is manifest in all your interactions with others.

Dian returned to Karisoke in the summer of 1983 after a three-year absence. She went out to contact Group 5. “The females—Effie, Puck, Tuck, Poppy and all their young followed by Pantsy and Muraha—just came to cuddle next to me and all their young followed,” she wrote to a friend in Ithaca. “Stacey, they really did KNOW me immediately after staring into my face, belch vocalizing, coming 12 feet upon initial contact, then to rest all on top of me and around me, building their day nests in the sun while allowing their kids to swarm, chew, smell, whack, pull hair. . . . I could have died right then and wished for nothing more on earth simply because they remembered. ”

Dian was ebullient. After a promotional book tour arranged by her publisher, she returned again to Karisoke, now her permanent home.

All of the time Dian worked in Rwanda, she was forced to renew her tourist visa every two months. She had to hike painfully down the mountain, drive in a waiting van to Ruhengeri, and then ride for two or three hours in the “taxi”—actually an alarmingly overcrowded minibus, similar to the matatu of Nairobi—to the capital, Kigali. Then she would wait for days in the office of the tourism and parks director, who always insisted he was too busy to see her and provide the letter she needed to secure the new visa.

In December 1985, while in Kigali on one such trip, she complained of her problems to a dinner companion. He suggested she see the secretary-general in charge of immigration. She did, and within ten minutes her passport was stamped with a visa good for two years. He told her the next one would be good for ten years if she wanted it.

“She was so ecstatic,” remembers Rosamond Carr. “She went running around Kigali, hugging everyone she saw and telling them, ‘Now I can go up on the mountain in absolute peace, I don’t have to go down again. I’ve got a visa for two years.’ She was literally over the moon.”

Two weeks later Dian was killed in her cabin by a swipe of a panga that split her skull diagonally from her forehead to the opposite corner of her mouth. It was the day after Christmas.

When I visited her camp in 1989, a plastic Santa Claus was still hanging on the wall of her living room; her breath was still in the flaccid balloons she had strung along the ceiling. Her blood was still on the carpet.

Dian’s murder attracted a storm of press attention. Special memorial tributes were held in Washington, New York, and California. Dian’s mother, Kitty, attended the California tribute. To pay her respects to her daughter, who had subsisted largely on potatoes for nearly two decades, who had given her life to the survival of animals, Kitty Price wore a full-length mink coat.

In her will Dian directed that the proceeds from her book and from the movie rights to it should go to the Digit Fund. Her parents wanted the money for themselves. They contested the will and won on the grounds that the document was only a draft.

Dian was buried in the gorilla graveyard in back of her cabin. The name she had asked to have on her wooden marker was Nyiramachabelli.

Rosamond Carr had always wondered about the name. Nyira, she knew, meant woman or girl in Kinyarwanda, but she had never thought Dian’s explanation of the name was quite right. When Rosamond asked her housemen about the name, they told her they didn’t know. An educated Rwandan friend said the name meant “Dian Fossey.”

Finally Rosamond asked a Rwandan physicist working in Gisenyi: “He said it’s hard to describe, but I insisted. He said, ‘Well, in Rwanda, when there’s a family and in the family there is one little girl who is smaller than the others, and does everything quick, quick, quick, we call her Nyiramachabelli.’ But why would anyone call Dian, who was six feet tall, Nyiramachabelli? He said he didn’t know.”

One of Rosamond’s housemen, Sembagare, finally admitted that Nyiramachabelli was what people had called Alyette DeMunck, the small, quick, birdlike woman who used to climb the mountain with Dian; when Alyette stopped coming, they applied the name to Dian. Rosamond talked to Alyette about it. She smiled and said, “Yes, I know. But Dian was very proud to be called Nyiramachabelli. She loved it. I’m very happy Dian never knew.”

© 2009 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

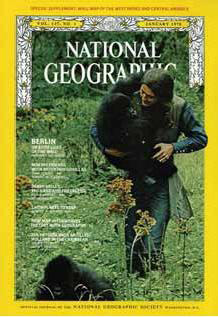

Featured on the January 1970 cover of National Geographic, Dian Fossey became a heroine to millions.

MICHAEL P. TURCO

Jane Goodall, today the best-known scientist in the world, and the first in the scientific sisterhood that would become known as The Trimates.

RODNEY BRINDAMOUR / NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC STOCK

Biruté Galdikas followed Jane and Dian into the field, working in Borneo with the third and least-known of the great apes.

M. NEUGEBAUER / ARDEA.COM

Jane will soon enter a fifth decade of fieldwork with the chimpanzees of Gombe.

JEN AND DES BARTLETT / BRUCE COLEMAN / PHOTOSHOT

Paleoanthropologist Louis Leakey with wife, Mary, and fossil Zinjanthropus, “our dear boy.”

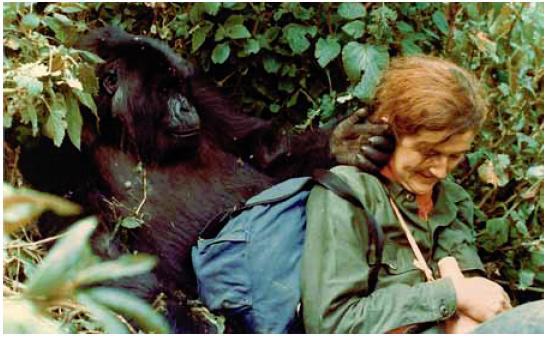

THE DIAN FOSSEY GORILLA FUND INTERNATIONAL

Puck tenderly caresses Dian’s face.

MICHAEL P. TURCO

In the swamps of Borneo, Biruté emulates a mother orangutan to raise the orphans.

JOHN GIUSTINA / BRUCE COLEMAN / PHOTOSHOT

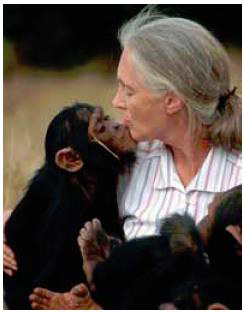

Jane with rescued chimp at Sweetwater Sanctuary in Kenya.

YANN ARTHUS BERTRAND / ARDEA.COM

Dian and her trackers found and destroyed thousands of illegal snares.

SY MONTGOMERY

Flo’s daughter Fifi with baby Faustino; Flo’s legacy lives on at Gombe.

SY MONTGOMERY

Like people coming down a path, chimps often walk in single file.

SY MONTGOMERY

In Fifi’s close-knit family, frequent, tender grooming helps maintain social bonds.

SY MONTGOMERY

When I visited Dian’s cabin shortly after her murder, her breath was still in the balloons hung as Christmas decorations.

SY MONTGOMERY

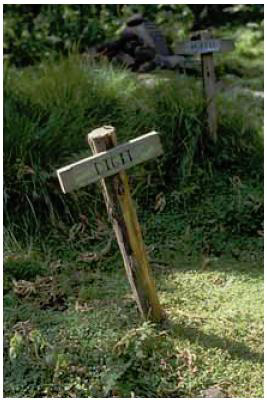

The gorilla graveyard, in which Dian is buried.

SY MONTGOMERY

Dian Fossey’s grave is now a tourist destination.

SY MONTGOMERY

By klotok, the journey up the Sekoyner-Cannon river to Camp Leakey took most of the day.

SY MONTGOMERY

Biruté with her Dayak husband, Pak Bohap, in front of their home in Pasir Panjang during my visit in 1988.

SY MONTGOMERY

Orangutans are the most elusive of the Great Apes.

SY MONTGOMERY

Playful young orangutans enlivened every corner of Camp Leakey.

SY MONTGOMERY

Exploring the world by mouth, orphaned baby orangutans ate our soap and drank our shampoo.

SY MONTGOMERY

Supinah holds her new baby.