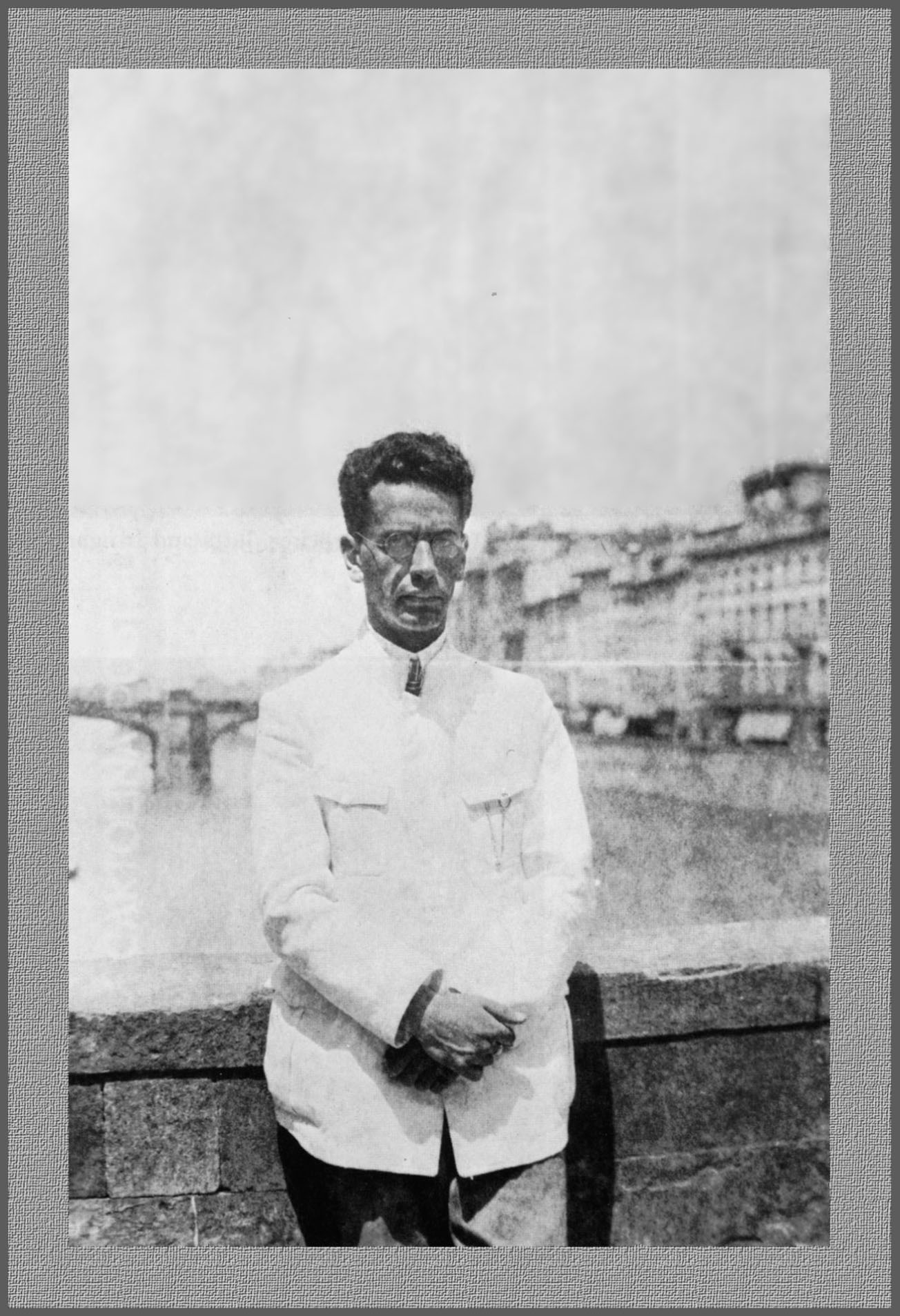

FIG. 2. Karl Löwith, Florence, 1925. Photo courtesy of J. B. Metzlersche Verlagsbuchhandlung and Carl Ernst Poeschel Verlag, Stuttgart 1986.

Hannah Arendt: Kultur, “Thoughtlessness,” and Polis Envy

Explaining Totalitarianism

IN 1945, Thomas Mann gave a memorable speech at the Library of Congress entitled “Germany and the Germans.” Attempting to come to grips with the so-called German catastrophe—which, had it been confined to the Germans alone, might not have been nearly so catastrophic—he observed: “There are not two Germanys, an evil and a good, but only one, which through devil’s cunning, transformed its best into evil.”1 Mann realized that the horrors of Nazism could not be attributed to an arbitrary instance of mass hypnosis. The problem was not just Hitler or “Hitlerism,” but the fact that a vast majority of Germans had consciously and willingly met their infamous Führer halfway. Hitler’s seizure of power was not some kind of unforeseeable “industrial accident” or Betriebsunfall, as postwar Germans were fond of claiming, that befell the nation from outside and that left German traditions unscathed. Instead, the genocidal imperialism that the Nazis unleashed upon Europe represented the consummation of certain long-term trends of German history itself. It was in this spirit that Mann, in “On Germany and the Germans,” implored his countrymen not to go too easy on themselves. Instead they needed to plumb the depths of their national patrimony, from Herder to Heidegger, in order to ferret out and confront those specifically German delusions that facilitated disaster.

Both Hannah Arendt and Martin Heidegger set forth accounts of the German calamity. Both were adamant about interpreting Nazism primarily as a European phenomenon rather than as typically German, an approach that has certain merit. After all, Germany was far from alone in opting for a fascist-authoritarian solution to the political ills of the interwar period. At the same time, this position’s interpretive weakness lies in the fact that it systematically underestimates the Germanic specificity of the Third Reich.

To say that Arendt’s explanation was the more successful, despite its flaws, is hardly controversial. In many respects, Heidegger’s own narrative was simply delusory, a retrospectively contrived psychological prophylaxis against his own enthusiastic support for the regime. In Heidegger’s view, everything that came to pass—the war, the extermination camps, the German dictatorship (which he never renounced per se)—was merely a monumental instance of the “forgetting of Being,” for which the Germans bore no special responsibility. After the war, he went so far as to insist that German fascism was unique among Western political movements in that, for one shining moment, it had come close to mastering the vexatious “relationship between planetary technology and modern man.” In Heidegger’s estimation, therein lay the “inner truth and greatness of National Socialism.” But ultimately “these people [the Nazis] were far too limited in their thinking,” he claimed.2 Pathetically, Heidegger was left to replay in his own mind the way things might have been had Hitler (instead of party hacks) heeded the call of Being as relayed by Heidegger himself. Nazism might thereby have realized its genuine historical potential. Fortunately, the world was spared the outcome of this particular thought experiment.

Arendt set forth her account in The Origins of Totalitarianism, a work that deservedly earned her an international reputation. In Origins, Arendt identified the most important phenomenon of twentieth-century politics. As a form of political rule, totalitarianism was a novum whose structures and practices were unprecedented. The regimes of Stalin and Hitler differed qualitatively from traditional tyrannies, which, as a rule, left a compliant civil population in domestic peace. Not so these modern dictatorships, which, in keeping with a spirit of total mobilization, demanded the active complicity of their subjects. The images of these regimes most likely to endure are the choreographed mass rallies staged by Hitler and Mussolini, immortalized in films like Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will. In these spectacles, pliable human material was to be sculpted (to employ one of Mussolini’s pet metaphors) into a form suitable for totalitarian rule.

Arendt captured the predominant features of the totalitarian experience as no one had before. But her analysis contained glaring weaknesses that left subsequent generations of scholars confused. Her account was divided into three main headings: anti-Semitism, imperialism, and totalitarianism. She scorned the traditional method of causal historical explanation—the idea that certain historical circumstances were produced by determinant antecedent variables—as deterministic. Instead, in the tradition of the Geisteswissenschaften, she held that whereas the natural sciences “explain,” in the writing of history we seek to “understand.” She thus characterized anti-Semitism and imperialism as “elements” that, at a certain point, “crystallized” into modern totalitarian practice.

Yet what it was that catalyzed this mysterious process of crystallization remained murky in her account. To wit: there have been numerous historical formations in which the elements of anti-Semitism and imperialism had been prominent, though nothing resembling totalitarianism emerged. Historically speaking, there have been only two genuinely totalitarian societies: Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union under Stalin.3 In both cases, concentration camps were emblematic. Origins, however, suffered from a massive imbalance. Part III on totalitarianism dealt almost exclusively with National Socialism. The discussion of Stalinism was appended as though it were an afterthought. Moreover, whereas National Socialism and its horrendous crimes would be inconceivable without anti-Semitism, which was the linchpin of Nazi ideology, in the worldview of Bolshevism it played a negligible role. If, then, one of the essential elements is entirely absent in one of the main instances of totalitarian rule, what kind of explanatory power might the model as a whole retain?

Moreover, in Origins Arendt’s “Jewish problem”—that is, her problem with her own Jewish identity—was apparent in a way that foreshadowed the terms of the Eichmann controversy some twelve years hence. Already the lines between perpetrators and victims had been blurred. The Jews were faulted for being an apolitical people—as if that were a lot they had chosen. Arendt concluded that, in many instances, the Jews had foolishly brought historical persecution upon themselves.4 Jewish arrogance, in the form of the myth of the chosen people and the “in-group–out-group” mentality in which it found historical expression, played a prominent role in her narrative. From this perspective, it would not require too large a logical leap to arrive at the rather perverse judgment that, in certain respects, the Jews deserved their fate, just as the protagonists of Greek tragedies can be said to have deserved their fate. Although Arendt had not yet explored the complex interrelationship between the Jewish Councils, collaboration, and (non-) resistance, in many respects the theoretical groundwork for some of the more controversial features of the Eichmann book had been established.

A Dangerous Liaison

Not only did Arendt have a Jewish problem, she also had a “Heidegger problem.” In many respects, the two were integrally related. The amorous liaison during the 1920s between Heidegger and Arendt has been public knowledge for years. The contours of their affair, however, have remained an object of speculation. The recently published Heidegger-Arendt correspondence offers important insight into the dynamics of their libidinal entanglement—and an “entanglement” it was.

At the time their affair began in 1925, Heidegger was a thirty-five-year-old father of two who had already acquired the reputation, despite a scanty publication record, as a philosophical wunderkind. He was known colloquially as the “magician of Messkirch” (Heidegger’s birthplace), and students from all over Germany flocked to his courses in droves. To avoid the crunch, he scheduled his lectures at the crack of dawn. Karl Löwith once described Heidegger’s seductive podium persona as follows:

We gave Heidegger the nickname “the little magician from Messkirch.” … He was a small dark man who knew how to cast a spell insofar as he could make disappear what he had a moment before presented. His lecture technique consisted in building up an edifice of ideas which he then proceeded to tear down, presenting the spellbound listeners with a riddle and then leaving them empty-handed. This ability to cast a spell at times had very considerable consequences: it attracted more or less pathological personality types, and, after three years of guessing at riddles, one student took her own life.5

At the time, Arendt was a far cry from the proud New York intellectual warrior she would become later in life. She was a frail eighteen-year-old from the East Prussian city of Königsberg. Though she hailed from a well-to-do, assimilated Jewish family, Hannah experienced her share of hard knocks at an early age. Her father died a prolonged, horrible death from syphilis in 1913, his agonies extending from Arendt’s second to seventh year. Several months before her father’s death, her beloved maternal grandfather also died. A few years later, her mother remarried. Overnight, the precocious young Hannah acquired two half-sisters with whom she had precious little in common. Her sense of displacement was no doubt acute. In an impassioned, youthful autobiographical tract portentously titled “The Shadows,” she lamented her “helpless, betrayed youth.”6

The liaison between Arendt and Heidegger was dangerous because, in the idyllic university town of Marburg, Heidegger could have been dismissed from his teaching position had the lovers been found out. Heidegger had already acquired a considerable reputation, in the Socratic tradition, as a seducer of youth. His wife, Elfride, was notoriously jealous, especially of the train of female students who were mesmerized by Heidegger’s spell. She was also a notorious anti-Semite. In the 1920s, she once suggested to Günther Stern—soon to become Arendt’s first husband—that he enlist in a local Nazi youth group. When Stern replied that he was Jewish, Frau Heidegger merely turned away in disgust.

Heidegger and Arendt were an unlikely couple: she, the fetching young Jewish woman from a Baltic-cosmopolitan milieu; he, the Schwarzwalder, a lapsed Catholic and convinced provincial. According to Elzbieta Ettinger, Arendt’s exotic Eastern features “stood in stark contrast to the Teutonic Brunhildas he was close to: his mother and his wife.”7 In one of his more fatuous texts of the 1930s, “Why We Remain in the Provinces,” Heidegger delivered a humorless encomium to the joys of provincial life. Today, the essay reads like a parody: “Let us stop all this condescending familiarity and sham concern for Volk-character and let us learn to take seriously that simple, rough existence up there.”8 As a rule, this völkisch mentality went hand in hand with a broadly shared anti-Semitism. Unfortunately, Heidegger remained true to the stereotype. In his infamous 1933 Freiburg University rectoral address, he was at pains to eulogize the “forces that are rooted in the soil and blood of the [German] Volk.”9 A letter of reference from 1929 shows him lamenting the rampant “Jewification” (“Verjudung”) of the German spirit—some four years prior to the advent of Nazi rule. And in a recently unearthed letter from 1933, Heidegger proffers a crude ideological denunciation of the Jewish philosopher Richard Hönigswald:

Hönigswald comes from the neo-Kantian school which stands for a philosophy that is tailor-made for liberalism. The essence of man is dissolved into a free-floating consciousness and this, in the end, is thinned down to a general, logical world-reason. On this path, on an apparently rigorous scientific basis, the path turns away from man in his historical rootedness and his national [volkhaft] belonging to his origin in earth and blood [Boden und Blut]. Together with this goes a conscious forcing back of all metaphysical questioning, and man is counted as nothing more than a functionary of an indifferent, general world-culture. This is the fundamental stance from which Hönigswald’s writings stem.10

This letter portrays a worldview that, if not quite Nazi, was capable of reconciling itself seamlessly with National Socialist aims and goals.

Some commentators have pointed to Heidegger’s dalliance with Arendt, combined with his cordial relationships with other Jewish students, as evidence of a philo-Semitic streak. Yet Heidegger had no compunction about serving on the board of the Academy for German Law with the likes of Julius Streicher, chief purveyor of Nazi anti-Semitic pornography and editor of Der Stürmer. The board’s president, Hans Frank, was the future German governor of Poland. Later, both Streicher and Frank were convicted at Nuremberg of “crimes against humanity.” The Academy’s avowed credo was to reestablish the basis of German law in accordance with the principles of “Race, State, Führer, Blood, [and] Authority.” Heidegger labored in the company of such men until 1936, a good two years after he had resigned his Freiburg rectorship. By then he had severed ties with all of his former Jewish students.11

It seems that Heidegger’s relationship with Arendt, while not without tenderness, was profoundly exploitative. Given their discrepancies in age, social standing, and background, it could hardly have been otherwise. It was Heidegger who initiated the affair. Arendt, an impressionable eighteen-year-old, was clearly awestruck by this formidable embodiment of Geist, a man nearly twice her age. Ettinger reconstructs the prehistory of their acquaintanceship as follows:

That Hannah Arendt was drawn to [Heidegger] is not surprising. Given the powerful influence he exerted on his students it was almost inevitable. Neither her past—that of a fatherless, searching youngster—nor her vulnerable, melancholic nature prepared her to withstand Heidegger’s determined effort to win her heart. She shared the insecurity of many assimilated Jews who were still uncertain about their place, still harboring doubts about themselves. By choosing her as his beloved, Heidegger fulfilled for Hannah the dream of generations of German Jews, going back to such pioneers of assimilation as Rahel Varnhagen.12

The two met clandestinely (usually in Arendt’s Marburg student garret), at Heidegger’s urging, in accordance with the demands of his schedule. Inevitably, the demands of secrecy became confusing and burdensome to both. Approximately a year after the affair began, Arendt decided to transfer to another university. She viewed the move as an act of self-sacrifice on Heidegger’s behalf. As she explained in a letter, she reached this decision, “because of my love for you, to make nothing more difficult than it already was.”13 But it seems that Heidegger was also pressuring her to leave, while hoping that they could continue their surreptitious rendezvous under circumstances in which the likelihood of their being discovered would be diminished. To facilitate this end, Heidegger arranged for Arendt to study with his friend Karl Jaspers in Heidelberg.

Though Arendt’s departure from Marburg was nominally voluntary, she was clearly wounded by Heidegger’s callous treatment. It was as though he had repaid her intimacy and trust by summarily banishing her. Upon moving to Heidelberg, she retaliated by refusing to provide him with her new address. At this point, Heidegger seized the initiative and sent one of his students, Hans Jonas, to seek her out. Arendt’s trysts with Heidegger continued for another two years at forlorn whistle-stops along the Marburg-Heidelberg railway line. Shortly after Heidegger received his permanent appointment at Freiburg in 1928, he abruptly broke off the affair. In response to the bitter news, Arendt ended her letter with a melodramatic premonition: “‘And with God’s will / I will love you more after death.’”14 But her threat, if it actually was one, was never carried out. The following year, she married Günther Stern (soon to become Günther Anders).

To the very end, however, Arendt remained in Heidegger’s thrall. In 1974, the year before her death, she wrote to him, in barely sublimated code: “No one can deliver a lecture the way you do, nor did anyone before you.”15 And when they reconciled following the war, Heidegger confided to Arendt that she had been “the passion of his life.”16

Negative Symbiosis

Inevitably, in the late 1920s, Arendt’s Jewish problem came to the fore, as it would for so many other assimilated German Jews. For many, the realization that, in the eyes of their German acquaintances, they were more Jewish than German—despite their ardent attempts at acculturation—came as a shock. It must have been especially painful to discover their own Jewishness for the first time via the acid bath of anti-Semitism. To express this dilemma in Sartrian terms, their Jewishness had been “constituted” by the gaze of anti-Semites.17 Suddenly, they were forced to confront the fact that the lives they were leading had been predicated on a series of illusions—above all, the illusion that they were as German as any of their non-Jewish fellow citizens. The process of disillusionment was particularly bitter for well-educated Jews, who labored under the delusion that German culture or Bildung was the great equalizer, their “entry ticket” to the privileges of German society.

Arendt’s biography fit squarely within this mold. She, too, had be lieved that, if one only tried hard enough to internalize the virtues of Geist, the doors to German society would magically open: “Jews who wanted ‘culture’ left Judaism at once, and completely, even though most of them remained conscious of their Jewish origins,” she once remarked.18 As she told an interviewer in 1964: “As a child I did not know that I was Jewish…. The word ‘Jew’ was never mentioned at home when I was a child. I first met up with it through anti-Semitic remarks … from children on the street. After that I was, so to speak, ‘enlightened.’” When in the course of the same interview she was asked what remained of her German upbringing, she responded: “What remains? The language remains.”19 Thirty years prior to Auschwitz, Kafka, with preternatural foresight, arrived at a considerably more ambiguous verdict concerning the virtues his native tongue: “Yesterday it occurred to me that I did not always love my mother as she deserved and as I could, only because the German language prevented it. The Jewish mother is no ‘Mutter,’ to call her ‘Mutter’ makes her a little comic…. ‘Mutter’ is peculiarly German for the Jew, it unconsciously contains, together with the Christian splendor, Christian coldness.”20

Arendt characterized problems of Jewish identity as “perplexing, troubling, and evasive.”21 She described her Jewishness as an indubitable fact. As she put it: “I belong to [the Jewish people] as a matter of course, beyond dispute or argument.”22 But whether Jewishness had much significance for her beyond this ontological “being-so-and-not-otherwise” is doubtful. As Richard Bernstein has pointed out, the preceding declaration “is not to answer to the question of Jewish identity, but to evade it.”23 Indeed, beyond such perfunctory declarations of a shared existential fate—a Jewish counterpart to the German idea of Schicksalgemeinschaft (a “community of fate”)—her reflections on matters of Jewish identity are notably lacking in substance. As a rule, Arendt adhered to a problematic separation between “Jewishness” qua brute ontological datum and “Judaism” qua religion—an idea that, she admits frankly, never held much of an attraction for her. What it is that remains of “Jewishness” when one has jettisoned “Judaism” was a matter she never addressed.

In the eyes of their fellow Germans, those Jews who avidly pursued Bildung never shed their taint as social climbers or parvenus. The more successfully Jews integrated themselves within the framework of German society, the more strident—and politically well-organized—grew their anti-Semitic detractors. Whereas an earlier generation of anti-Semites had decreed that the criterion for admission to German society was that Jews relinquish their “national peculiarities”—essentially, that they become Germans instead of Jews24—for a later generation, that demand no longer sufficed. Instead, according to the new doctrine of racial anti-Semitism, try as they might, Jews as a nation or race could never become German. Illustrative of this trend was the fact that Wilhelm Marr’s inflammatory 1879 tract, The Triumph of Judaism over Germanism, went through twelve editions in six years. As Marr declared, giving voice to the new racialist credo: “There must be no question of parading religious prejudices when it is a question of race and when the differences lie in blood.”25 Ironically, whereas previously Jews had been criticized for remaining too attached to their medieval rites and ghetto mores, during the Second Empire they were scorned for having abandoned their traditional Jewish backgrounds and trying to “pass for German”—in essence, for being a people without an identity.

The leading representatives of German classicism—Kant, Herder, Goethe, and Wilhelm von Humboldt—viewed Bildung as a sublime cosmopolitan-democratic ideal; its substance was, in principle, accessible to everyone who persevered, Germans and Jews alike. Jewish intellectuals and religious leaders revered the classical period as a golden age of German spiritual life; they gave themselves body and soul to its precepts and promises. German Jews were allegedly “Jewish by the grace of Goethe,” an edition of whose collected works had, for liberal Jews, become a standard bar mitzvah gift. As late as 1915, the philosopher Hermann Cohen expressed this trust as follows: “Every German must know his Schiller and his Goethe and carry them in his heart with the intimacy of love. But this intimacy presupposes that he has won a rudimentary understanding of Kant.”26

Yet a later generation of Germans emphatically turned their backs on the universal designs of Bildung, shamelessly glorifying instead the virtues of German particularism. The historian Heinrich von Treitschke, who coined the infamous slogan, “The Jews are our misfortune,” vigorously lent his energies and reputation to the anti-Semitic campaigns of the Gründerzeit. For von Treitschke, the attacks against the Jews were merely a “brutal but natural reaction of German national feeling against a foreign element.”27

Many Jews believed—in retrospect, naively—that World War I presented a golden opportunity to prove their loyalty as German citizens. Instead, they met with recriminations, the infamous wartime census, and the “stab-in-the-back” myth—all of which were a sad harbinger of trends to come.

With the economic collapse of 1929 and the Nazis’ stunning electoral success of the following year, the demise of the fragile Weimar Republic became imminent. A turning point in the course of German history had occurred. The rationalizations of earlier years abruptly ceased to hold and, for Jews, a wholesale reorientation was required. During the 1920s, anti-Semitism had become an article of faith among Germany’s so-called “national revolutionaries.” Ernst Jünger gave voice to a belief that was widely shared when, doing von Treitschke one better, he remarked circa 1930 that, “To the same extent that the German will gains in sharpness and shape, it becomes increasingly impossible for the Jews to entertain even the slightest delusion that they can be Germans in Germany; they are faced with their final alternatives, which are, in Germany, either to be Jewish or not to be.”28

How, then, might one evaluate this momentous transformation from traditional, religion-based anti-Semitism to its modern, mass-political variant? The historian Peter Pulzer aptly summarizes these developments as follows: “The audience’s vague and irrational image of the Jew as the enemy probably did not change much when the orators stopped talking about ‘Christ-slayers’ and began talking about the laws of blood. The difference lay in the effect achieved. It enabled anti-Semitism to be more elemental and uncompromising. Its logical conclusion was to substitute the gas chamber for the pogrom.”29

Caritas and Existenz

In 1928, Arendt wrote a dissertation, under Jaspers’ supervision, on Saint Augustine’s concept of love. The essay represented an orthodox phenomenological reconsideration of Augustine’s doctrines. Faithful to the training she had received from Heidegger and Jaspers, the demigods of German Existenzphilosophie, she gave existential questions pride of place in her study. Arendt addressed the quandary of how one might reconcile a theory of this-worldly, neighborly love with Augustine’s conviction that an authentic relation to the world must be thoroughly mediated by one’s relationship to God. With this focus, Arendt attempted to work through the problem of “Being-with-others”—a key category in Being and Time—as it pertained to Augustine’s doctrines.30 The pathos of Augustine’s conversion experience bore marked affinities with the concerns of existentialism. It resonated in Heidegger’s notion of “authentic resolve” as well as in Jaspers’ concept of the “limit-situation.” In a post-Nietzschean, atheological spirit, however, both thinkers tried to translate such religious sentiment into secular terms. For Heidegger, it pertained, above all, to the isolated individual’s authenticity in confronting his or her own existential nothingness or death.

Arendt’s work also contains an implicit critique of Heidegger, both as a philosopher and as a person. In a footnote, Arendt faults her mentor (and former paramour) for his impoverished phenomenological understanding of the concept of “world.” For Heidegger, she suggests, “world” has become an utterly impersonal and loveless notion. As such, his description of it threatens to backslide into the “objectivating” discourse that Being and Time sought to surmount. Thus Arendt declares that, for Heidegger, “world” has become “ens in toto, the decisive How, according to which human existence relates to, and acts toward, the ens”—a characterization that, in her view, barely transcends what it means to be “ready-to-hand.” Conversely, her stated aim in the dissertation is to develop a dimension of “world” that Heidegger has neglected: “the world conceived as the lovers of the world [view it],”31 adumbrations of which she claims to find in the early Christian ideal of caritas, which figures prominently in the Confessions. Given the intensity of their affair and the trauma of their parting, the autobiographical implications of Arendt’s focus are not hard to discern.

Arendt published the dissertation in 1929 to mixed reviews. Theologians were put off by her unwillingness to take the existing literature into account. All in all, it is a strikingly un-Arendtian document; the inflections of her mature philosophical voice are barely audible. It is the work of a disciple, narrowly textual in orientation and focus, devoid of the originality that would characterize her subsequent work. In certain respects, the work stands out as an embarrassing testimonial to the delusions of assimilationism. It was written at a point in Arendt’s life when she still entertained hopes of a university career amid the woefully conservative milieu of German academic mandarins.32

Some commentators have claimed that the Augustine study fore-shadows Arendt’s mature philosophical concerns. It contains, for example, hints of her concept of “natality”—the uniquely human capacity to establish new beginnings. Yet, on closer inspection, the argument for intellectual continuity proves difficult to sustain; for whereas the later Arendt is known primarily as a philosopher of “worldliness,” such concerns are hard to reconcile with an orientation as manifestly other-worldly as Augustine’s. Moreover, Augustine’s commitment to the values of transcendence undermines Arendt’s attempt to interpret his doctrine in terms that are meaningful from the standpoint of human intersubjectivity or community. In Love and Saint Augustine, Arendt seeks to develop a notion of neighborly love in conjunction with a doctrine for which “worldliness” is the equivalent of “temptation.” For Augustine, love of one’s neighbor must never be intrinsic or for its own sake. Such love would merely be sinful. Instead, neighborly love, the virtues of human community, must always be mediated by our all-encompassing relationship to God. As Arendt herself recognizes: “This very faith will thrust the individual in isolation from his fellow individuals in the divine presence…. Faith takes man out of the world, that is, out of a certain community of men, the civitas terrena.”33 The notion of community that Arendt discovers in Augustine is morbid and oblique, drenched in a veil of theological tears: it is that mournful community of the fallen or sinful who can trace their lineage back to the first sinner, Adam. As Arendt expresses it: “Humanity’s common descent is its common share in original sin. This sinfulness, conferred with birth, necessarily attaches to everyone. There is no escape from it. It is the same in all people. The equality of the situation means that all are sinful.”34

The conceptual divide separating this Jugendschrift from Arendt’s later concerns has been best articulated by the philosopher herself. In The Human Condition (1958), she openly polemicizes against the “worldlessness” of the early Christian civitas dei—as exemplified by the work of Augustine—in contrast with the genuine human achievements of “plurality” and “publicness”:

To find a bond between people strong enough to replace the world was the main political task of early Christian philosophy and it was Augustine who proposed to found not only Christian brotherhood but all human relationships on charity…. The bond of charity between people, while it is incapable of founding a public realm of its own, is quite adequate to the main Christian principle of worldlessness and admirably fit to carry a group of essentially worldless people through the world.35

Moreover, in Arendt’s subsequent study of Rahel Varnhagen, a Berlin Jew, she developed withering critiques of both the delusions of “introspection”—the psychological corollary to “worldlessness”—and the false consciousness of Jewish assimilationism. There can be no doubt about the fact that such criticisms were meant as a harsh rejection of Arendt’s own youthful Germanophilia. Thus, for compelling biographical reasons, her polemical repudiation of the Augustine study could hardly have been more explicit. After all, in Augustine it is only via introspection—“the turn to the inner voice of conscience,” as he puts it—that we begin to abandon the temptations of worldliness in favor of the eternal life of salvation. Conversely, in the Varnhagen study, Arendt associated introspection with a meretricious and self-deluded worldlessness. As a psychic mechanism of denial, introspection preserves a semblance of inner autonomy while endorsing a fatal indifference to worldly concerns. Ultimately, it represents a form of narcissistic self-deception: “Lying can obliterate the outside event which introspection has already converted into a purely psychic factor. Lying takes up the heritage of introspection, sums it up, and makes a reality of the freedom that introspection has won.”36

Rahel Varnhagen: From Parvenu to Pariah

Following the traumatic breakup with Heidegger, Arendt bid an unsentimental farewell to German philosophy. Heidegger’s brusque rejection undoubtedly enhanced her sense of Jewish inferiority. In her own mind, she must have wondered what role her Jewishness had played in their parting. As the Weimar Republic tottered toward the brink of collapse, many issues must have been confused in her mind. German philosophy, which she had once assumed to be her calling, now seemed fully implicated in the deteriorating political situation. On a personal level, Arendt was shocked at the remarkable ease with which the leading representatives of German Kultur had, overnight, metamorphosed into convinced Nazis and anti-Semites. In 1933, after Heidegger had become Nazi rector of Freiburg University and assumed responsibility for instituting anti-Jewish decrees, Arendt sent him an accusatory letter. In a later interview, she expressed her profound disillusionment with her fellow German intellectuals in unequivocal terms:

The problem … was not what our enemies did but what our friends did. In the wave of Gleichschaltung [the Nazification of German society], which was relatively voluntary—in any case, not yet under the pressure of terror—it was as if an empty space formed around one. I lived in an intellectual milieu, but I also knew other people. And among intellectuals Gleichschaltung was the rule, so to speak. But not among the others. And I never forgot that. I left Germany dominated by the idea—of course somewhat exaggerated: Never again! I shall never again get involved in any kind of intellectual business. I want nothing to do with that lot.37

In retrospect, it would seem that she conceived this indictment with Heidegger’s case foremost in mind.

Arendt’s circumstantially compelled confrontation with her own heretofore repressed Jewish identity led to a dramatic shift in her intellectual interests. As soon as she had finished the Augustine dissertation, she began research on a biographical study of the Enlightenment maitresse de salon, Rahel Varnhagen. The book’s subtitle, “The Life of a Jewess,” was indicative of Arendt’s new area of concern. Only in hindsight, and in light of what we now know about her star-crossed romance with Heidegger, does the profoundly autobiographical tenor of the Varnhagen book become clear.

Varnhagen’s story was that of a woman who, like Arendt, had for a long time struggled to keep her Jewish identity at a distance through the rationalizations and delusions of Innerlichkeit or “inwardness.” In the end, however, she learned—like her biographer—to reconcile herself to her pariah status as a Jewish woman in the midst of an unaccepting and at times actively hostile Gentile society. Rahel’s dying words, as recounted by Arendt, were: “The thing which all my life seemed to me the greatest shame, which was the misery and misfortune of my life—having been born a Jewess—this I should on no account now wish to have missed.”38

A widely accepted Enlightenment precept held that the Jews, a backward and uncultured people, could only gain acceptance once they shed their Jewishness, an ungainly medieval atavism. According to Arendt, Prussian Jews of Rahel’s day suffered from a type of collective false consciousness: “Jews did not even want to be emancipated as a whole; all they wanted was to escape from Jewishness, as individuals if possible.”39

The turning point in Rahel’s life came early—just as it had for Arendt by virtue of her encounter with Heidegger. In her struggle to gain acceptance in a semi-enlightened Prussian society, Rahel decided on a solution that was fairly common among Jewish parvenus of the day: baptism and intermarriage.

With her assimilationist dreams rapidly fading, Rahel found herself an eminently suitable beau in the person of Count Karl von Finckenstein, an occasional visitor to her salon. Soon, the two were betrothed. Varnhagen’s expectations for a new life as Countess von Finckenstein—a life of unblemished social acceptance—were high. Suddenly and unexpectedly, however, their engagement fell through. It seems that his immediate family disapproved of the prospective bride. More importantly, von Finckenstein felt ill at ease in the overtly bourgeois salon ambience, where titles counted for naught, and where what one was mattered more than who one was. In this latter respect, the Count—Rahel’s ticket to social respectability—had precious little to show for himself.

Little interpretive genius is required to appreciate how profoundly Arendt must have identified with her literary protagonist and co-religionist. Rahel, a self-described Shlemihl—neither rich, nor beautiful, and a Jew—was the archetype of the Jewish “pariah,” a Weberian characterization that would become the leitmotif for Arendt’s understanding of the diaspora experience.40 Nor does it require much of an imaginative leap to appreciate the painfully autobiographical terms in which Arendt viewed the von Finckenstein episode. The parallel with Heidegger’s courtship of her, which also ended in an excruciatingly abrupt parting of the ways, must have struck her as uncanny. In all of these respects, Varnhagen must have appeared to Arendt as an eerily perfect doppelgänger. Even their responses to the dilemmas of pariahhood—quiescent acceptance followed by vigorous self-affirmation of Jewishness—mesh to a tee.

But there is another aspect of the Varnhagen volume that merits scrutiny in light of Arendt’s aggrieved relations with Heidegger. The study opens with a heavy-handed and sustained polemic against the delusions of German romanticism: against the perils of a sensibility for which the values of “inwardness” have been transformed into the highest aim of life. Expressed in the idiom of Arendt’s later philosophy, the romantic cult of interiority suffered acutely from a lack of “worldliness.” Her unsparing critique of the aberrations of the German intelligentsia—the delusions of Geist—contains some of the most impassioned writing of her entire oeuvre:

Sentimental remembering is the best method for completely forgetting one’s own destiny. It presupposes that the present itself is instantly converted into a “sentimental” past…. The present always first rises up out of memory, and it is immediately drawn into the inner self, where everything is eternally present, and converted back into potentiality. Thus the power and autonomy of the soul are secured. Secured at the price of truth, it must be recognized, for without reality shared with other human beings, truth loses all meaning. Introspection and its hybrids engender mendacity.

Introspection accomplishes two feats: it annihilates the actual existing situation by dissolving it in mood, and at the same time it lends everything subjective an aura of objectivity, publicity, extreme interest. In mood the boundaries between what is intimate and what is public become blurred; intimacies are made public, and public matters can be experienced and expressed only in the realm of the intimate—of gossip.41

Rahel Varnhagen: The Life of a Jewess thus embodies an uncompromising rejection of the false hopes of Arendt’s youth. She zealously dismisses her girlhood delusion—one shared by Rahel—concerning the egalitarian nature German Kultur: a sphere in which people were purportedly judged on the basis of merit rather than rank or ethnicity. These were the illusions that had collapsed for Varnhagen in the aftermath of her breakup with von Finckenstein. They came to grief for Arendt following her rejection by Heidegger amid a rising tide of German anti-Semitism. Inevitably, these two circumstances—one highly personal, the other political—must have been maddeningly conflated in Arendt’s mind.

The passionate tenor of Arendt’s Varnhagen critique helps us make sense of her embittered renunciation, in the aforementioned interview, of German intellectuals and intellectual life—“Never again! I shall never again get involved in any kind of intellectual business.” For it was the intellectuals who had betrayed her, turning against her almost overnight, in solidarity with the new regime. The Nazis were her declared enemies. Her philosophical intimates—Germany’s spiritual elite, those steeped in the virtues of inwardness, the cultured heirs to Goethe, Hölderlin, and Rilke—were the ones from whom she least expected betrayal.

All of these dilemmas must have crystallized for Arendt in May 1933. It was then that she learned of Heidegger’s sensational entry into the Nazi Party, as well as of his pro-Nazi rectoral address, which concluded with a blusterous ode—in good romantic tradition—to the “Glory and Greatness of the New [German] Awakening.” But the worst was still to come. Later that same year, Freiburg’s new “Rector-Führer,” stumping on behalf of the new regime, would end his speeches with rhetorical flourishes such as: “Let not doctrines and ideas be the rules of your Being. The Führer alone is the present and future German reality and its law,” punctuated by a “threefold Sieg Heil!” Some thirteen years later, when Arendt first tried to assess Heidegger’s Nazism in the pages of Partisan Review, she tellingly observed that Heidegger’s “whole mode of behavior has exact parallels in German Romanticism”; he was “the last (we hope) romantic—as it were, a tremendously gifted Friedrich Schlegel or Adam Mueller.”42 In other words, Heidegger’s case epitomized the risks of romantic “worldlessness,” along with the concomitant megalomania and delusions of grandeur. Following the war, Thomas Mann also looked to the debilities of romanticism to account for Germany’s descent into barbarism: above all, romanticism’s fascination with “a certain dark richness of soul that feels very close to the chthonian, irrational, and demonic forces of life”; a fascination that led to “hysterical barbarism, to a spree and a paroxysm of national arrogance and crime, which now finds its horrible end in national catastrophe, a physical and psychical collapse without parallel.”43 But, needless to say, there are profound limits to explanations of Nazism that remain confined to the parameters of Geistesgeschichte.

“A Confirmation of an Entire Life”

Arendt and Heidegger reconciled upon her return to Germany in 1950. The reunion transformed her from one of his harshest critics into one of his most staunch defenders. At the time, Heidegger remained banned from German university life. His reputation irreparably damaged as a result of his status as a Nazi collaborator, he stood in desperate need of a reliable publicist and goodwill ambassador. Arendt fit the bill. As a Jewish intellectual with an international reputation and a leading critic of totalitarianism, her support could help parry the persistent accusations concerning Heidegger’s Nazism. Arendt was ecstatic about their reunion. She believed that she had recovered the dreams of her youth, the worse for wear, perhaps, but recovered nevertheless. “That evening and that [next] morning,” she wrote, “are a confirmation of an entire life. In fact, a never-expected confirmation.”44

Arendt became Heidegger’s de facto American literary agent, diligently overseeing contracts and translations of his books. In a moment of desperation, Heidegger, elderly and cash-poor, contemplated auctioning off the original manuscript of Being and Time. Unworldly in matters of Geld, where was he to turn for advice? To a Jew, of course. Arendt dutifully complied, consulting a Library of Congress expert and offering detailed counsel.

In her correspondence with Jaspers immediately following the war, Arendt’s characterizations of the Freiburg sage had been relentlessly critical. She derogated Heidegger’s lectures on Nietzsche as “absolutely horrible [and] chatty.” And further: “That life in Todtnauberg [in Germany’s Black Forest], this railing against civilization, and writing Sein with a ‘y’ is in reality a kind of mouse hole into which he withdrew, assuming with good reason that the only people he will have to see are pilgrims filled with admiration for him; no one is likely to climb 1200 meters just to make a scene.”45 In the aforementioned Partisan Review essay, she lambasted Heidegger’s philosophy, faulting his “fundamental ontology” for having regressed behind Kant’s notion of human autonomy. “Heidegger’s ontological approach,” charged Arendt, “hides a rigid functionalism in which Man appears only as a conglomerate of modes of Being, which is in principle arbitrary, since no concept of Man determines his modes of Being.”46

Following their reconciliation, however, her tone changed abruptly. Thereafter, she systematically downplayed the gravity and extent of Heidegger’s Nazi past. In her contribution to a Festschrift commemorating Heidegger’s 80th birthday, Arendt went out of her way to dispute the relationship between Heidegger’s philosophy and his enlistment for Hitler. Gone were the earlier impassioned inculpations of romantic inwardness—that quintessentially German spiritual mania, for which the world could remain a hovel, so long as the thinker’s palace of ideas remained intact. Absent, too, was any trace of her earlier critical portrayal of Heidegger as “the last (we hope) romantic.” Arendt instead meekly copped a plea on behalf of her embattled mentor. In an abrupt and contradictory turnabout, she claimed that Nazism was a “gutterborn” phenomenon and, as such, had nothing to do with the life of the mind. She readily bought into the myth that Heidegger had practiced “spiritual resistance” against the regime during his lecture courses of the 1930s—a myth that has been effectively refuted by Heidegger biographer Hugo Ott. And, in a poorly veiled rejoinder to Adorno’s powerful critique of Heidegger in The Jargon of Authenticity (in a 1963 article, Adorno had claimed that Heidegger’s philosophy was “fascist to its innermost core”), she added that, whereas Heidegger had taken certain “risks” in defiance of the regime, “The same cannot be said of the numerous intellectuals and so-called scholars … who rather than speaking of Hitler, Auschwitz, and genocide … have recourse to Plato, Luther, Hegel, Nietzsche or even Heidegger, Jünger, or Stefan George, in order to remove the dreadful phenomenon from the gutter and adorn it with the [rhetoric of] the human sciences or intellectual history.”47 According to this new interpretive tack, the realm of German Kultur, on whose mantle Arendt had hung the hopes of her youth, bore no responsibility for the German catastrophe. To her, of course, Heidegger was the living embodiment of both that realm and her youthful hopes. In her correspondence, Arendt proffered an even more spirited defense of her embattled mentor, one that at times bordered on blind loyalty. She characterized Heidegger’s 1933 rectoral address as a text that, “though in spots unpleasantly nationalistic” was “by no means an expression of Nazism.” “I doubt,” she continued, “that Heidegger at that time had any clear notion of what Nazism was all about. But he learned comparatively quickly, and after about 8 or 10 months, his whole ‘political past’ was over.”48

How did Heidegger repay such blind devotion? Sadly, but true to form, he remained psychologically incapable of acknowledging the fact that his former student mistress had blossomed into an intellectual of world stature. When the German translation of The Origins of Totalitarianism appeared in the early 1950s, Heidegger responded with months of icy silence—a resounding non-response. And several years later, when Arendt proudly sent him the German edition of The Human Condition, which she had wanted to dedicate to Heidegger (“it owes you just about everything in every regard”), she commented ruefully in a letter to Jaspers:

I know that he finds unbearable that my name appears in public, that I write books, etc. Always, I have been virtually lying to him about myself, pretending the books, the name, did not exist, and I couldn’t, so to speak, count to three, unless it concerned the interpretations of his works. Then, he would be quite pleased if it turned out that I can count to three and sometimes to four. But suddenly I became bored with the cheating and got a punch in the nose.49

After they reestablished contact after the war, Arendt tried to engage Heidegger in a dialogue about the European catastrophe—in particular, about the tragic fate of European Jewry. In response, Heidegger, true to form, served up his usual array of specious metaphysical ob-fuscations. Imploring Arendt to comprehend “Being” without reducing it to the terms of conventional secular “history,” he continued by observing: “the fate of Jews and Germans has its own truth that cannot be reached by our historical reckoning. When evil has happened and happens, then Being ascends from this point on for human thought and action into mystery; for the fact that something is does not mean that it is good and just.”50 As Seyla Benhabib has observed with reference to Arendt’s failure to respond to such blatant mystifications: “In [this] episode of their correspondence Arendt’s readiness to indulge Heidegger’s cultivated sense of his own political naïveté takes a toll on her forthrightness.”51

Hitler’s Banal Executioners

In 1963, Arendt published Eichmann in Jerusalem. She never fully recovered from the scandal that ensued as a result of a brief discussion in which she implied that the behavior of Jewish Council officials was on a par with that of the Nazi executioners. She claimed that, had the Jewish leaders refused to cooperate with the Nazis, more Jews would have survived; we now know that claim to be untenable. In certain cases, collaboration bought precious time. However, her argument represented a tasteless equation of victims and executioners. Moreover, her account neglected to convey the unspeakable duress under which the Jewish leaders were required to function—by any standard, a grave omission.

Steering clear of historical complexities, Arendt contended that, for a Jew, “this role of the Jewish leaders in the destruction of their own people is undoubtedly the darkest chapter of the whole dark story.” She went on to discuss “the totality of the moral collapse the Nazis caused in respectable European society—not only in Germany but in almost all countries, not only among the persecutors but also among the victims.”52

In Eichmann in Jerusalem, Arendt relied extensively on Raul Hilberg’s magisterial work, The Destruction of the European Jews. Though Hilberg’s work was pathbreaking in many respects, it was far from flawless. The treatment of the role of the Jewish Councils was one of its major deficiencies. Hilberg relied primarily on non-Jewish sources that often portrayed Jews according to the basest of anti-Semitic stereotypes: Jews were pliable and servile, easily compromised by appeals to self-interest. Thus, according to Hilberg, Judenrat (Jewish Council) collaboration was a fairly simple affair, the consummation of an ingrained Jewish predisposition to acquiesce in the face of persecution. However, this simplistic portrayal of the Jewish response has become increasingly difficult to maintain in view of mounting evidence compiled by more recent research.

The strategy of the Jewish Councils was to exchange goods and labor in the hope of saving Jewish lives. Under the circumstances, it seemed a reasonable approach. It was a course that proved effective until the final deportations, when, without warning, all other options disappeared. Moreover, such negotiations sought to take advantage of tensions among the German high command over whether the exploitation of Jewish labor for war aims or the anti-utilitarian logic of the “Final Solution” should prevail.

Like Hilberg, Arendt failed to distinguish the various stages of Jewish cooperation with their Nazi persecutors. These gradations, however, are crucial to evaluating Jewish culpability. During the initial mass deportations, many Judenrat leaders refused to hand over Jewish lives when commanded to do so by the Nazis. When confronted with Jewish intransigence, the SS either arrested the Jewish leaders or executed them on the spot. Often, the Nazis then proceeded to hand-pick a second generation of Jewish leaders, about whose willingness to cooperate there could be no doubt. It was largely under this Nazi-selected second regime of Judenrat officials that the deportations proceeded. As Yehuda Bauer observes in A History of the Holocaust: “The histories of most ghettoes can be divided … into two periods: before and after the first mass murders.”53 In the eastern Galician town of Stanislawow, for example, three successive Judenrat leaders were executed because of their refusal to hand over Jews.

In Judenrat: The Jewish Councils in Eastern Europe under Nazi Occupation (1972), Isaiah Trunk demonstrated conclusively how Jewish “collaboration,” far from being voluntary, was predominantly a product of German coercion. On almost all occasions, the Nazis forced the Jews to establish the councils, coerced Jews to serve on them, and compelled their cooperation, often upon pain of the most brutal reprisals. Moreover, circumstances permitting, many of the councils supported Jewish resistance activities. Some, such as the Warsaw ghetto council, were democratically organized. In Arendt’s unsympathetic portrayal, however, such crucial distinctions were flattened out.

Few would deny that corruption existed among segments of the Jewish leadership. As Gershom Scholem observed: “Some among them were swine, others were saints. There were among them also many people in no way different than ourselves, who were compelled to make terrible decisions in circumstances that we cannot even begin to reproduce or construct.” What he found troubling in Arendt’s account was what he called “a kind of demagogic will-to-overstatement.” As Scholem comments, “I do not know whether they were right or wrong. Nor do I presume to judge. I was not there.”54

As Michael Marrus has aptly observed, as the Eichmann polemic unfolded, “it became apparent how thin was the factual base on which [Arendt] had made her judgments.” He concludes with the following sober caveat: “The Jewish negotiations with the Nazis … were in retrospect, pathetic efforts to snatch Jews from the ovens of Auschwitz as the Third Reich was beginning its death agony. Yet it should be mentioned that, however pathetic, these efforts seemed sensible to some reasonable men caught in a desperate situation.”55

Generally speaking, Arendt’s broad condemnation of the Jewish leadership displayed little comprehension of—let alone sympathy toward—the contingencies and extremes of a set of dire historical circumstances. Concerning Rumkowski’s corrupt reign in the Lodz ghetto, it has often been pointed out that, had Soviet troops arrived a few months sooner, he would have gone down in history as a hero instead of a traitor.56

At times, Arendt’s insensitivity to the dimensions of the Jewish tragedy was striking. In a spirit of German-Jewish arrogance, she described Eichmann’s Israeli prosecutor, Gideon Hausner, as “a Galician Jew [who] … speaks without periods or commas … like a diligent schoolboy who wants to show off everything he knows … ghetto mentality”—the ultimate slight from a high-born Jew. She imprudently referred to the Berlin Jewish leader Leo Baeck (the head of the Reichsvereinigung der deutschen Juden) as the “Jewish Führer,” characterized Eichmann as a “convert to Judaism,” claimed that Jewish cooperation “was of course the cornerstone of everything he [Eichmann] did,” and, on countless occasions, stooped to compare the nationalist aspirations of Zionism and National Socialism—thereby suggesting a macabre equation of victims and perpetrators.57 Her suggestion that, in the 1930s, the Zionists and Nazis shared a common vision and worked hand in hand—at one point, she went so far as to describe the 1930s as Nazism’s “pro-Zionist period”—seemed spiteful and insensitive.58 Finally, in a letter to Jaspers, she expressed the tasteless opinion that, “Ben Gurion kidnapped Eichmann only because the reparation payments to Israel were coming to an end and Israel wanted to put pressure on Germany for more payments.”59

She supplemented this lack of empathy for the victims with the contention that the man on the witness stand, Adolf Eichmann—second only to Himmler and Heydrich in responsibility for the Final Solution—was “banal.” Accepting Eichmann’s own calculated denials at face value, she argued that he possessed little awareness of his own culpability. She came to the conclusion that Eichmann’s crimes were devoid of “intentionality.” Instead, Eichmann was merely a cog in a massive bureaucratic machine in which wrongdoing had become the norm—hence, his “banality.” Hilberg, whose study in many respects pioneered the “functionalist” account of the Holocaust, took offense at the suggestion that Eichmann’s character could be adequately described in such terms:

[The “banality of evil”] is certainly a description of her thesis about Adolf Eichmann and, by implication, many other Eichmanns, but is it correct? In Adolf Eichmann, a lieutenant colonel in the SS who headed the Gestapo’s section on Jews, she saw a man who was “déclassé,” who had led a “humdrum” life before he rose in the SS hierarchy, and who had “flaws” of character. She referred to his “self-importance,” expounded on his “bragging,” and spoke of his “grotesque silliness” in the hour when he was hanged, when—having drunken a half-bottle of wine—he said his last words. She did not recognize the magnitude of what this man had done with a small staff, overseeing and manipulating Jewish councils in various parts of Europe … preparing anti-Jewish laws in satellite states and arranging for the transportation of Jews to shooting sites and death camps. She did not discern the pathways that Eichmann had found in the thicket of the German administrative machine for his unprecedented actions. She did not grasp the dimensions of his deed. There was no “banality” in this “evil.”60

The most forceful accusation Arendt could mobilize against Eichmann and his fellow perpetrators was the charge of “thoughtlessness”—a characterization that seriously misapprehended the nature of Nazi ideology, its power as an all-encompassing worldview. In Arendt’s view, the Nazis were less guilty of “crimes against humanity” than they were of “an inability to think”—a charge which, if taken at face value, risks equating their misdeeds with those of a dim-witted child. Moreover, Arendt’s reliance on “banality” and “thoughtlessness” as central explanatory concepts signified a remarkable change of heart in relation to The Origins of Totalitarianism, where she had pointedly characterized National Socialism as an incarnation of “radical evil”—that is, as far from banal. Ironically, it was Arendt herself who had convincingly shown in Origins that one of the hallmarks of totalitarian regimes was that they made resistance all but impossible.61

Perhaps Arendt’s greatest failing as an analyst of the Jewish response to Nazism was that, regarding the most tragic hour of modern Jewish history, she came off seeming hard-hearted and uncaring. Even a stalwart supporter such as the historian Hans Mommsen was forced to avow, in the Preface to the German edition of Eichmann in Jerusalem, that “The severity of her criticism and the unsparing way in which she argued seemed inappropriate given the deeply tragic nature of the subject with which she was dealing.” Moreover, concludes Mommsen, the Eichmann book “contains many statements which are obviously not sufficiently thought through. Some of its conclusions betray an inadequate knowledge of the material available in the early 1960s.”62

Arendt never seemed to understand what all the fuss was about. She complained that the “Jewish Establishment” was orchestrating a conspiracy against her. She attributed the bad press she was receiving in Israel to the fact that the same Ashkenazi types who had manned the Jewish Councils were pulling the strings behind the scenes. Arendt viewed herself as superior to those Eastern Jewish ghetto-dwellers who in her account had acquiesced in their own destruction. She identified herself with European intellectual traditions that were more refined and sublime—the tradition of Geist. She had studied—and fallen in love—with Martin Heidegger, one of its leading representatives. Could it have been those allegiances—uncanny and subterranean—that in some way led her to purvey such calumnies about the Jews in the Eichmann book? Could such remarks have been meant to absolve the Messkirch magician of his crimes on behalf of a regime that sought to wipe out the Jews, by insinuating that, in certain respects, they were no better than the Nazis?

Functionalism Revisited

The idiosyncrasies of Arendt’s relationship to Judaism would remain a matter of limited biographical interest were she not one of the leading interpreters of totalitarianism and the Holocaust. However, her “banality of evil” thesis, as articulated in the Eichmann book, has been become the cornerstone of the so-called “functionalist” interpretation of Auschwitz. For this reason alone, the historiographical and political stakes involved in reassessing her legacy are immense.

According to the functionalist approach, the Holocaust was primarily a product of “modern society.” In his analysis of revolutionary France, Tocqueville had already shown how the democratic leveling characteristic of modernity was conducive to despotism.63 Social leveling produced a dangerous asymmetry between atomized individuals, who had suddenly been deprived of their traditional social standing (the estates), and the centralized power of the democratic leader. In Origins, Arendt built on Tocqueville’s approach to explain the system of organized terror—and the corresponding inability of atomized masses to resist—that was one of the predominant features of totalitarian society.

The functionalist approach emphasizes the role of bureaucracy in producing a qualitatively new, impersonal form of industrialized mass death. Thus, at a certain point, the “machinery of destruction” (Hilberg) begins to take on a life of its own. Since the bureaucratic perpetrators operate at a remove from the actual killing sites, they are impervious to the horror unleashed by their actions. From Arendt’s perspective, the Nazis’ misdeeds were “crimes without conscience.” The nature of the killing process, which had been organized in accordance with modern principles of bureaucratic specialization and the division of labor, meant that the executioners were unaware that they had done anything wrong. As Arendt explains:

Just as there is no political solution within the human capacity for the crime of administrative mass murder, so the human need for justice can find no satisfactory reply to the total mobilization of a people for that purpose. Where all are guilty, nobody in the last analysis can be judged. For that guilt is not accompanied by even the mere appearance, the mere pretense of responsibility. So long as punishment is the right of the criminal—and this paradigm has for more than two thousand years been the basis of the sense of justice and right of Occidental man—guilt implies the consciousness of guilt, and punishment evidence that the criminal is a responsible person.64

According to Arendt, the Nazi perpetrators displayed neither “consciousness of guilt” nor a sense of personal responsibility for the crimes they had committed. She described the Nazi henchmen as “co-responsible irresponsibles” insofar as they were simply cogs in a “vast machine of administrative mass murder.”65 The uniqueness of the Holocaust lay in the creation of a new, peculiarly modern type of mass murderer: the Schreibtischtäter or desk murderer.

Consequently, for Arendt, Auschwitz had few implications for German history or German national character: “In trying to understand what were the real motives which caused people to act as cogs in the mass-murder machine, we shall not be aided by speculations about German history and the so-called German national character,” she confidently remarked.66 “The mob man, the end-result of the ‘bourgeois,’ is an international phenomenon; and we would do well not to submit him to too many temptations in the blind faith that only the German mob-man is capable of such frightful deeds.”67 Therefore, to punish the Germans collectively as a people, as some were inclined to do, would be misguided and senseless. Rather than being a specifically German crime, Nazi misdeeds were symptomatic of the ills of political modernity in general. They were of universal significance and, as such, could have happened anywhere. In fact, one of their distinguishing features was that they had been perpetrated neither by fanatics nor by sadists, but by normal “bourgeois.” In this connection, Arendt invoked Heidegger’s notion of “inauthenticity” to account for the perpetrators’ mediocrity cum bureaucratic conformism. The malefactors, she argued, were typical representatives of mass society. They were neither Bohemians, nor adventurers, nor heroes. Instead, they were family men in search of job security and career advancement. As Arendt affirms in “Organized Guilt and Universal Responsibility,” the average SS member is:

a “bourgeois” with all the outer aspect of respectability, all the habits of a good paterfamilias who does not betray his wife and anxiously seeks to secure a decent future for his children; and he has consciously built up his newest terror organization … on the assumption that most people are not Bohemians nor fanatics, nor adventurers, nor sex maniacs, nor sadists, but, first and foremost jobholders and good family-men…. Himmler’s over-all organization relies not on fanatics, nor on congenital murderers, nor on sadists; it relies entirely upon the normality of jobholders and family-men.68

“Organized Guilt and Universal Responsibility,” which Arendt wrote in 1945, contains the germ of her controversial “banality of evil” thesis. Nevertheless, in The Origins of Totalitarianism, Arendt described Nazism—its bureaucratic-administrative underpinnings notwithstanding—as a form of “radical evil.” The unspeakable horror of the events in question was still fresh. However, when she reformulated her thesis in the context of her report on the Eichmann trial—an event that became the occasion for a major reassessment of Nazism’s criminal essence—Arendt’s “functionalist” approach provoked shock and indignation.

There is certainly much that one can learn about the Final Solution by focusing on the bureaucratic nature of the killing process. Of course, there are scholars who would be quick to mention that the mobilized killing units in the East, the so-called Einstazgruppen, were found by the Nuremberg Military Tribunal to be responsible for the deaths of nearly two million Jews—and these deaths were anything but bureaucratic.

However, the functionalist thesis, as articulated by Arendt and others, tells only part of the story. What it fails to explain is the specificity of this particular genocide. Why was it that the Nazis explicitly targeted European Jews for extermination?69 To be sure, other groups had been victims of persecution and even annihilation. But concerning the centrality of anti-Semitism to the Nazi worldview there can be no doubt. Inevitably, an explanatory framework pitched at such a level of generality risks losing touch with the specificity of the phenomenon it seeks to comprehend. According to the functionalist approach, the extermination of the Jews could have happened anywhere. But the fact remains that it did not. It was not only the result of a brutal and impersonal “machinery of destruction”; it was also the product of the proverbial “peculiarities of German history.”

The main weakness of the functionalist approach is that it tends to underplay one of the most salient features of Nazi rule: ideology—specifically, the ideology of anti-Semitism. It would be difficult to imagine a regime more focused on total ideological control than was Nazism during its twelve-year reign. The horrors of Auschwitz are not explicable in strictly functionalist terms. Not all societies characterized by the predominance of “instrumental reason” are predisposed toward genocide. The distinctive feature of Auschwitz was not bureaucratic administration. Instead, it was the fact that modern bureaucratic methods were placed in the service of a fanatical and totalizing racist ideology. Unfortunately, Arendt ruled out such considerations a priori as a result of her idiosyncratic focus on the bourgeois paterfamilias, which, some eighteen years later, would reemerge as the linchpin of her “banality of evil” thesis.

Ultimately, Arendt’s methodological decision to concentrate on the bureaucratic aspects of Nazism, not to mention her astounding (though hardly unique) claim that “the crimes that had been committed at Auschwitz said nothing about German history or German national character,” itself needs explaining. Although in her response to Scholem concerning the Eichmann book, she denied having hailed from the milieu of the German left, she was not being entirely honest. It was clear that the influence of Heinrich Blücher—an ex-communist, autodidact, and non-Jew—on her thinking about totalitarianism and the course of European history was enormous, perhaps to such an extent that Arendt herself could barely recognize it.70 A December 1963 letter from Jaspers indicates that the banality of evil concept was originally Blücher’s: “Heinrich suggested the phrase ‘the banality of evil’ and is cursing himself for it now because you’ve had to take the heat for what he thought of.”71 An excessive emphasis on the “structural” features of the Nazi dictatorship has been a distinguishing feature of left-wing fascism analysis, from Franz Neumann to Raul Hilberg to Hans Mommsen. Conversely, the blind spot of this approach has been the ideological elements that derive from the “superstructure” instead of the sociological “base.”

But perhaps there is another biographical reason why Arendt opted for a functionalist approach. By emphasizing the “universal” constituents of the Final Solution at the expense of their specifically German qualities, she also managed to avoid implicating her country of origin—and thereby, narcissistically, herself. Perhaps it would have been psychologically difficult for Arendt to admit that Auschwitz was in fact a German invention, for such an avowal would have implicated her own early intellectual attachments as an assimilated German Jew, not to mention those of friends, professors, and so forth. Margaret Canovan puts her finger on the problem when she observes: “By understanding Nazism in terms not of its specifically German context but of modern developments linked to Stalinism as well, Arendt was putting herself in the ranks of the many intellectuals of German culture who sought to connect Nazism with Western modernity, thereby deflecting blame from specifically German traditions.”72 In a similar vein, Steven Aschheim points out that, “Arendt appears almost as a philosophical counterpart to the analyses of the more staid conservative German historians such as Gerhard Ritter and Friedrich Meinecke, who argued that the rise of Nazism had less to do with internal, ‘organic’ German development than with the importation of essentially alien and corrupting modern mass practices and ideologies.”73

Arendt’s supporters have long sought to make her “banality of evil” thesis plausible by pointing out that, though Eichmann himself may have been banal, the evil for which he was responsible certainly was not.74 The problem is that such helpful corrections remain at odds with the dominant tenor of Arendt’s narrative. By choosing “A Report on the Banality of Evil” as the subtitle of her book, she opened the floodgates of misunderstanding. Arendt certainly did not consider the Nazis’ crimes to be banal. But by relying on a generalizing narrative emphasizing the centrality of Schreibtischtäter, she confused the issue. Time and again she insisted that Eichmann was not a monster, that he was “terribly and terrifyingly normal”; yet one suspects that she had been duped by his unassuming courtroom demeanor. Moreover, while rewriting her story, she came across some fairly damning countervailing evidence: prosecutor Gideon Hausner’s revelation that Israeli psychiatrists had found Eichmann to be “a man obsessed with a dangerous and insatiable urge to kill,” “a perverted, sadistic personality.”75 Yet she decided to discount these claims and her thesis remained unaltered.

Thus Arendt selected a narrative framework for understanding the Holocaust that was consistent with her own profound cultural-biographical ambivalences as an assimilated German Jew. In her efforts to fathom the Jewish catastrophe—from Origins to Eichmann—one detects a profound unwillingness to face up to questions of German responsibility. It is as though Arendt looked everywhere except the place that was most obvious: the deformations of German historical development that facilitated Hitler’s rise to power. In her mind, all hypotheses other than this one were worth exploring: Jewish political immaturity, the excrescences of political modernity, the rise of mass society, bureaucracy, even “thoughtlessness.” That the Final Solution to the Jewish question was conceived, planned, and executed by fellow Germans was a fact that remained psychologically insupportable. Hence, nowhere was it accorded its due in her reflections and analyses. Dan Diner suggests provocatively that, in the last analysis, “her line of argument seems to have more in common with the self-exonerating perspective of the perpetrators, than with the anguish of the victims.”

Arendt tends towards a kind of universal extremism, which derealizes historical actuality. In her mind, Auschwitz becomes possible everywhere, although it turned out to have been executed by Nazi Germany. This tendency in juxtaposing the historical reality and the universal possibility of Auschwitz at reality’s expense, is a pervading undercurrent in Hannah Arendt’s argumentation. Such universalization tends to deconstruct the event—and to offend the victims.76

Action and Intimacy

Arendt’s “action-oriented” framework, as suggested by The Human Condition, has of late been uncritically celebrated as a type of panacea for the ills of political modernity: the instrumentalization of politics by “interests” and the colonization of the political by “society.” But such interpretations, decontextualized to a fault, underestimate the significant extent to which her political thought is rooted in the visceral antimodernism of Germany’s Zivilisationskritiker of the 1920s.77 This indebtedness, one might say, constitutes the “political unconscious” of Arendt’s mature thought; and it is in these terms that her intellectual affinities with Heidegger’s philosophical framework remain profound. Although this “critique of modernity” had adherents on both left and right sides of the political spectrum (the “romantic anti-capitalists” identified by Lukacs in The Theory of the Novel were its left-wing corollaries), there is no doubt that its most vocal proponents, such as Heidegger, decisively cast their lot with the political right.

The starting point for these critics of civilization was a rejection of “mass society” in all its forms. Heidegger’s condemnation of “everydayness” in Being and Time was merely a philosophically outfitted expression of this standpoint.78 But ultimately the concept of “mass society” remains too undifferentiated to do justice to the plurality of forms assumed by modern democracies. In those societies in which civil libertarian and parliamentary traditions remained strong, the values of “individualism” (in Durkheim’s sense) and civic consciousness predominated. Thus, it would be unjust to equate democratic rule with “mass society” tout court. The ideology of German exceptionalism (the proverbial Sonderweg) frequently subtended the “critique of civilization” as elaborated by right-wing luminaries such as Spengler, Moeller van den Bruck, Carl Schmitt, and others. Although this critique certainly contained an element of truth in the case of nations such as Germany, where the transition to modern political and economic forms tended to be violent and abrupt, in other cases such characterizations were merely polemical and erroneous.

Arendt’s filiations with this intellectual guild—filiations that are largely mediated through the work of Heidegger—echo clearly in her pejorative characterizations of “society,” which in her later philosophy becomes a figure for the ills of modern civilization simpliciter. As she remarks tellingly in The Human Condition: “the unconscious substitution of the social for the political betrays the extent to which the original Greek understanding of politics has been lost.”79 Today, Arendt continues,

We see the body of peoples and political communities in the image of a family whose everyday affairs have to be taken care of by a gigantic, nation-wide administration of housekeeping. The scientific thought that corresponds to this development is no longer political science but “national economy” or “social economy” or Volkswirtschaft, all of which indicate a kind of “collective housekeeping”; the collective of families economically organized into the facsimile of one super-human family is what we call “society,” and its political form is the “nation.”

Missing in this dismissive portrayal of “the social” is Marx’s brilliant, youthful description of the creative dimension of labor qua praxis in his Paris Manuscripts: labor as an essential form of human self-fulfillment, a manifestation of “species-being”; labor qua practical-critical “human sensuous activity.”80 Whereas the antidemocratic ontological tradition denies that self-fulfillment through praxis can ever be achieved by “the many,” the Hegelian Marxist tradition refuses to rest content with a situation in which happiness was accessible only to the privileged few. Thus, as another one of Heidegger’s children, Herbert Marcuse, glossed the relationship between labor and human self-realization: “Labor is man’s ‘act of self-creation’, i.e. the activity through and in which man really first becomes what he is by his nature as man. He does this in such a way that this becoming and being are there for himself, so that he can know and regard himself as what he is (man’s ‘becoming-for-himself’)…. Labor understood in this way, is the specifically human ‘affirmation of being’ in which human existence is realized and confirmed.”81