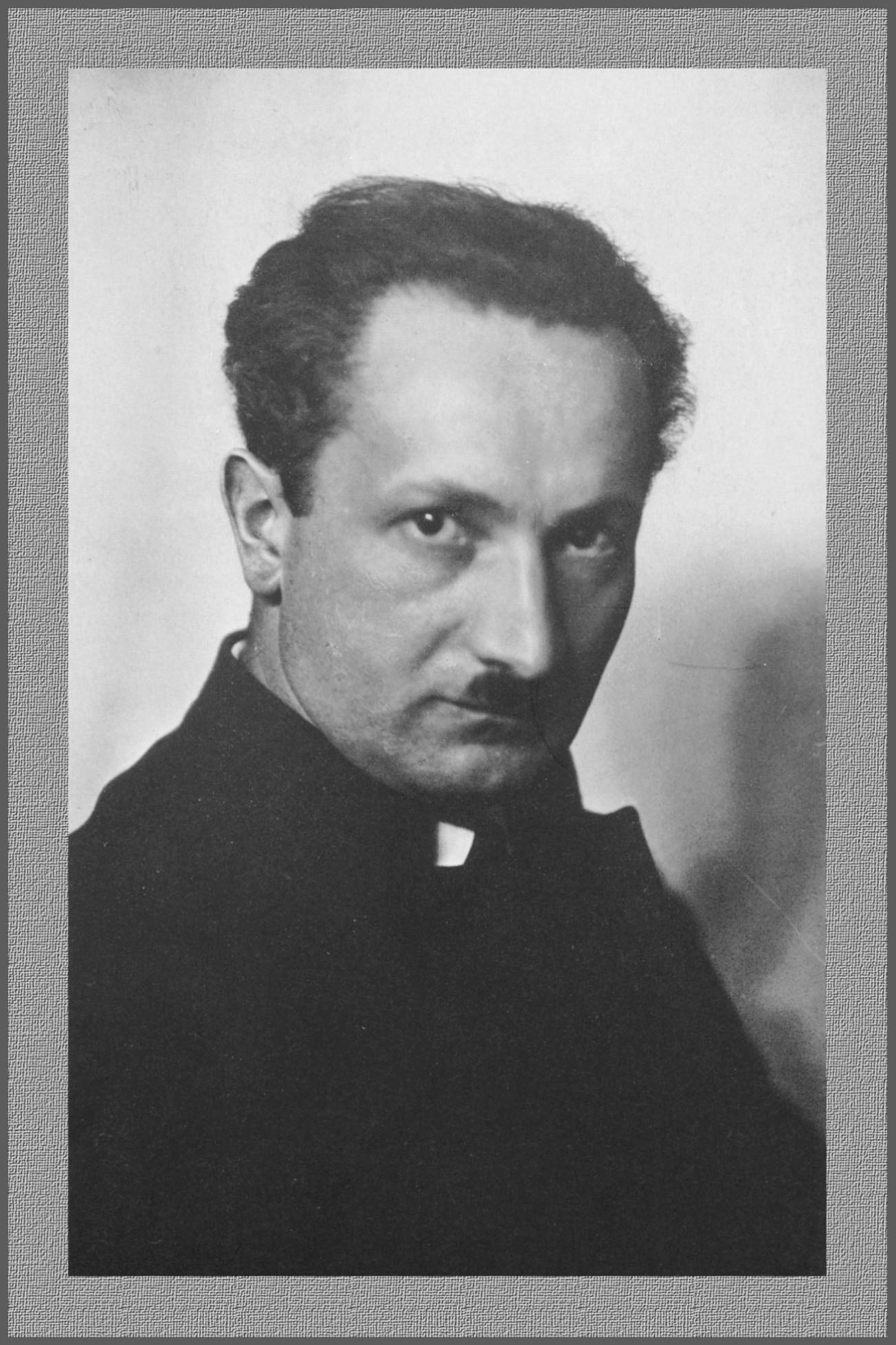

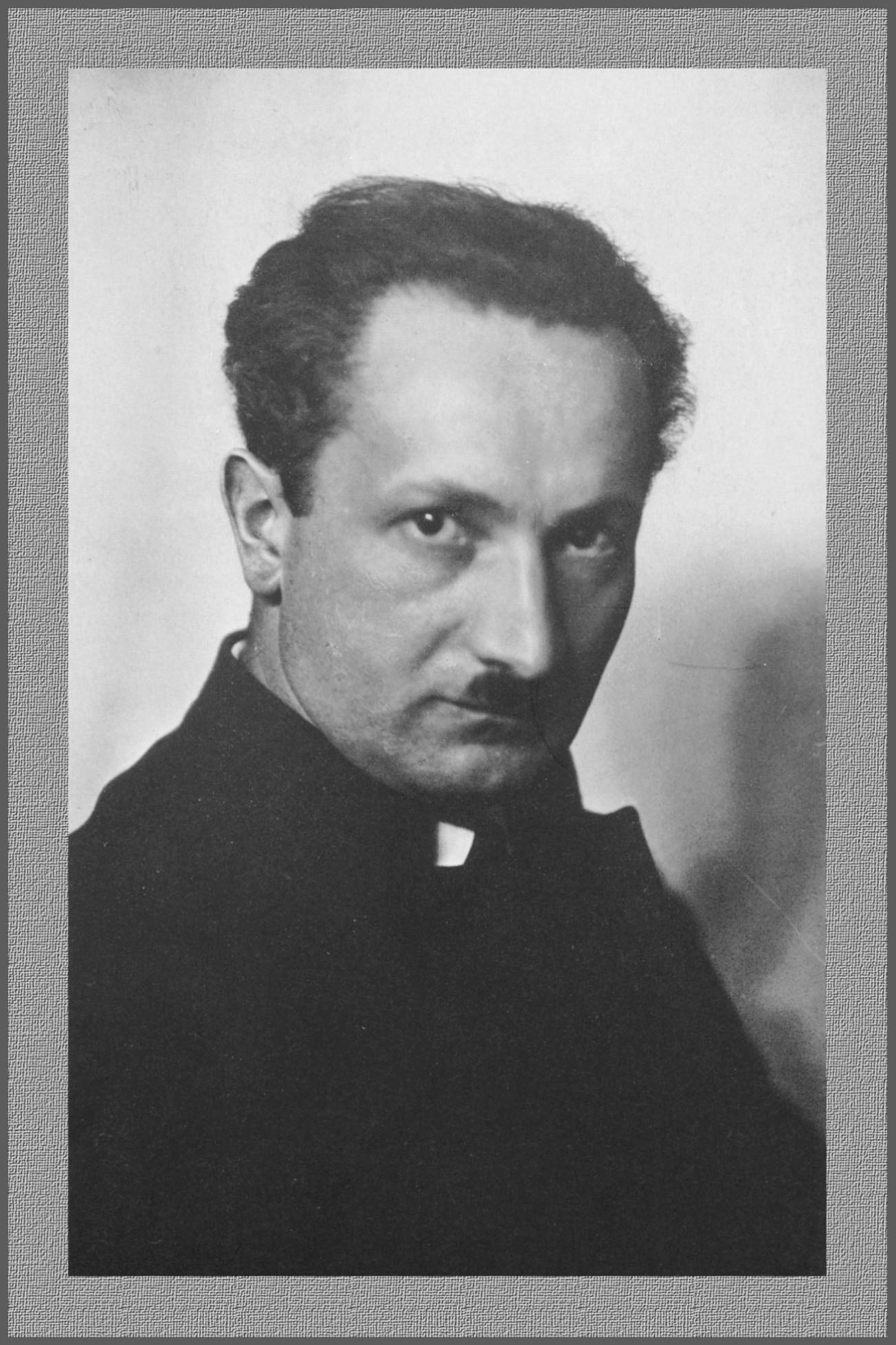

FIG. 5. Martin Heidegger, 1933. Photo courtesy of J. B. Metzlersche Verlagsbuchhandlung and Carl Ernst Poeschel Verlag, Stuttgart, 1986.

Arbeit Macht Frei: Heidegger as Philosopher of the German “Way”

An Aversion to Universal Concepts

HEIDEGGER resigned from the position of university rector in May 1934. His brief, though concerted, foray into politics was a cause for considerable disillusionment. Heidegger was done in not only by philosophical hubris and his lack of prior political experience, but also by a basic incapacity for political judgment. As Karl Jaspers, paraphrasing Max Weber, remarked concerning Heidegger’s case: children who play with the wheel of world history are smashed to bits. In many respects, Heidegger’s political maladroitness was an outgrowth of the “factical worldview” he had cultivated since his early break with Catholicism (1919). At that time, Heidegger began to embrace a pseudoheroic, post-Nietzschean standpoint determined partly by Nietzsche’s insight concerning the “death of God.” According to Nietzsche, the death of God was symptomatic of the delegitimation of the highest Western values and ideals. What remained was a devil’s choice between the abyss of nihilism and Nietzsche’s own alternative: the superman who was “beyond good and evil.”

Such were the “ontic” or historical origins of Heidegger’s Existenzphilosophie. In a world whose highest ideals had been discredited, what was there left to trust but the “facticity” of one’s own brute Being-in-the-world? This was Heidegger’s rejoinder to Descartes’ ego cogito sum. In Heidegger’s view, even this Cartesian ontological minimum assumed too much. Moreover, by defining human nature in terms of “thinking substance” (res cogitans), Descartes and modern philosophy established a series of pernicious rationalist prejudices: they assumed that what was distinctive about humanity was its capacity for theoretical reason, a predisposition with which Heidegger strove concertedly to break. Thus, in Being and Time, Heidegger went to great lengths to demonstrate that even more primordial (ülrsprünglich) than humanity’s intellectual capacities were a series of pre-rational habitudes and dispositions: moods, tools, language (which always “speaks man”), practical involvements and situations, Being-with-others, and so forth.

FIG. 5. Martin Heidegger, 1933. Photo courtesy of J. B. Metzlersche Verlagsbuchhandlung and Carl Ernst Poeschel Verlag, Stuttgart, 1986.

Heidegger’s philosophy betrays a fateful distrust of universal concepts, which are emblematic of a Western metaphysical tradition with which he hoped to break. Such concepts—“truth,” “morality,” “the good”—were representative of the theoretical tyranny of “representation” over “Being,” a characteristically Platonic intellectual falsification. According to Heidegger’s critique of metaphysics, the downfall of Western philosophy began when Plato shifted the locus of truth from the notion of “unconcealment” (aletheia) of things themselves to the notion of truth as “idea” or “representation.” As Heidegger remarks, with Plato, “Truth becomes orthotos, correctness of the ability to perceive and to declare something.”1 Thus, whereas originally truth was something proper to the Being of beings, with Platonism (and in this respect, the entire tradition of Western metaphysics merely follows Plato’s mistaken lead) its locus is transferred to the faculty of human judgment. Heidegger is merely being consistent, therefore, when in Being and Time he announces the need for a radical “destruction” of the history of Western philosophy.2

Needless to say, a rejection of universal concepts by no means entails a commitment to Nazism. Yet, with this radical philosophical maneuver, Heidegger left himself vulnerable to political movements whose major selling point—in opposition to the presumed decrepitude of Western liberalism—was an unabashed celebration of volkish particularism. Heidegger used the same normative criticisms he had brought to bear against Western rationalism as arguments against their corresponding political forms: cosmopolitanism, rights of man, constitutionalism. Search as one may through Heidegger’s voluminous philosophical corpus, one is extremely hard pressed to find a positive word concerning the virtues of political liberalism. His philosophical and political predilections were related to one another necessarily rather than contingently.

In a book written shortly before his death in 1945, Ernst Cassirer offered some perspicuous reflections on the relationship between Heidegger’s philosophy and the antidemocratic thought that was so much in vogue during the waning years of the Weimar Republic. Cassirer began by contrasting Heidegger’s “existential” point of departure with Husserl’s characterization of philosophy as “rigorous science”—an aim that, according to Cassirer, was “entirely alien to Heidegger.” Heidegger, Cassirer continues,

does not admit there is something like “eternal truth,” a Platonic “realm of ideas,” or a strictly logical method of philosophic thought. All this is declared to be elusive. In vain we try to build up a logical philosophy; we can only give an Existenzialphilosophie. Such an existential philosophy does not claim to give us an objective and universal truth. No thinker can give more truth than his own existence; and this existence has a historical character. It is bound up with the conditions under which the individual lives…. In order to express his thought Heidegger had to coin a new term. He spoke of the Geworfenheit of man (being-thrown).3

Cassirer is quick to avow that Heidegger’s ideas had little direct or immediate bearing on German political thought during the pre-Nazi period. But he also insists that the antirationalist animus that pervaded Heidegger’s doctrines was by no means ineffectual or without influence. Instead, as Cassirer observes, such approaches “did enfeeble and slowly undermine the forces that could have resisted the modern political myths…. A theory that sees in the Geworfenheit of man one of his principal characters [has] given up all hope of an active share in the construction and reconstruction of man’s cultural life. Such philosophy renounces its own fundamental theoretical and ethical ideals. It can be used, then, as a pliable instrument in the hands of political leaders.”4

The epistemological emphasis on “facticity,” which celebrates the particularism of one’s own immediate heritage/life/milieu, is a logical corollary of a perspective that esteems the concrete over the abstract. In this regard, the central position that Heidegger in Being and Time accords to “mineness” (Jemeinigkeit) is also indicative and revealing. When in 1933 Heidegger turned down an offer for a position at the University of Berlin, he justified his decision by glorifying the provincial values of locality and region, which he contrasted to the corrupting influences of modern city life:

The world of the city runs the risk of falling into a destructive error. A very loud and very active and very fashionable obstrusiveness often passes itself off as concern for the world and existence of the peasant. But this goes exactly contrary to the one and only thing that now needs to be done, namely, to keep one’s distance from the life of the peasant, to leave their existence more than ever to its own law, to keep hands off lest it be dragged into the literati’s dishonest chatter about “folk character” and “rootedness in the soil.”5

According to intimate Heinrich Petztet, the Freiburg philosopher felt ill at ease with big-city life, “and this was especially true of that mundane spirit of Jewish circles, which is at home in the metropolitan centers of the West.”6 In the late 1920s, Heidegger vigorously protested the growing “Jewification” (Verjudung) of German spiritual life.7 Thus, in Heidegger’s corpus, the boundaries between philosophy and weltanschauung are fluid and not impenetrable.8 To date, the predominant formal-philosophical interpretations of his work have systematically neglected its ideological dimensions, to their own detriment. By proceeding from a philosophical standpoint that consistently valued the particular over the universal, Heidegger’s thought was exposed from the outset to grave ethical and political deficits. This conclusion suggests that in seeking to account for Heidegger’s 1933 political lapsus, the existential standpoint he cultivated in the early 1920s is as important as the historical-biographical contingencies stressed by his defenders.

In My Life in Germany Before and After 1933, Löwith recounts a 1936 controversy in a Swiss newspaper over whether Heidegger’s political allegiances were consistent with his philosophy. A Swiss commentator had “regretted” the fact that Heidegger had “compromised” his philosophy by bringing it into contact with the “everyday”—that is, with contemporary German politics. Löwith, however, saw the matter quite differently. He realized that Heideggerianism, as a philosophy of existence, demanded contact with the everyday in order to satisfy its own categorial requirements. Thus, for Löwith, it was instead quite natural that “a philosophy that explains Being from the standpoint of time and the everyday would stand in relation to daily historical realities.”9 In Löwith’s view, the radicalism of Heidegger’s point of departure—naked “factical-historical life”—which devalued all traditional standpoints and received ideas, predisposed him to seek out radical political solutions. When later that same year Löwith had occasion to discuss the matter with Heidegger himself, Heidegger did not hesitate to avow that “his partisanship for National Socialism lay in the essence of his philosophy.” It was, Heidegger explained, his theory of “historicity”—one of the central categories of Division II of Being and Time—that constituted the “basis of his political engagement.”10

Historicity

In the massive secondary literature on Being and Time, the concept of historicity has suffered from relative neglect. Perhaps this is because it represents the aspect of Heidegger’s treatise where the philosopher stands in the greatest proximity to contemporary politics—and, hence, the moment at which the ideological aspects of his thought are most exposed. The reasons for this neglect are, in part, comprehensible. To date, Being and Time has been interpreted primarily in a Kierkegaardian/existential vein. It portrays a highly individualized Dasein wrestling with a series of basic ontological questions: the struggle for authenticity, the meaning of death, the nature of “care.” Yet the discussion of historicity, which in many respects represents a culmination of the book’s narrative, emphasizes a set of concerns—“destiny,” “fate,” the nature of authentic historical community (Gemeinschaft)—that are difficult to reconcile with the Kierkegaardian interpretation of the work as basically concerned with Dasein as an isolated individual “Self.” To be sure, were this Heidegger’s standpoint, it would be very difficult to reconcile the idea of historical political commitment with his intentions, and one would have to view Heidegger’s later political engagement as standing in contradiction with Being and Time’s basic ideals. It has often been argued in the philosopher’s defense that since Heidegger’s actions on behalf of Nazism demanded a surrender of individuality to the ends of the historical community, his political choice stood at cross-purposes with his philosophy. According to this reading, therefore, Heidegger’s political involvement represented an instance of inauthenticity. However, this interpretation forfeits its cogency once the concept of historicity—via which Heidegger unambiguously declares the centrality of collective historical commitment—is taken seriously.

As Löwith understood, it is but a short step from the facticity and particularism of individual Existenz to a celebration of volkish parochialism in collective-historical terms. For Heidegger, the mediating link between these two aspects of Dasein—the individual and the collective—was the conservative revolutionary critique of modernity. This strident lament concerning the world-historical decadence of bourgeois existence was first articulated in the work of Nietzsche, Spengler, and countless lesser Zivilisationskritiker. In Thomas Mann’s Confessions of an Unpolitical Man, for example, the antinomy between Kultur and Zivilisation occurs more than one hundred times.

That the standpoint of Being and Time is informed by the conservative revolutionary worldview suggests that Heidegger’s existential analytic, far from a purely “formal” undertaking, is in fact laden with ontic content—content derived from the Zeitgeist of the interwar years. The critique of “everydayness” in Division I—of “publicness,” “falling,” “curiosity,” and the “they”—emerges precisely therefrom. Inattention to this dimension of Heidegger’s work suggests the pitfalls of a purely text-immanent reading, in which the filiations between politics and philosophy are a priori extruded.

The intimate relationship between “fundamental ontology” and the “German ideology” should come as no surprise. Heidegger always insisted that ontological questioning can never be atemporal and never comes to pass in a historical void. Instead, it is unavoidably saturated with historicity. As he observes in Being and Time, “every ontology presupposes a determinate ontic point of view.”

Outfitted with a measure of historical perspective, we are now aware of the extent to which the early Heidegger made this critique his own.12 As Löwith comments:

Whoever … reflects on Heidegger’s later partisanship for Hitler, will find in this first formulation of the idea of historical “existence” the constituents of his political decision of several years hence. One need only abandon the still quasi-religious isolation and apply [the concept of] authentic existence—“always particular to each individual”—and the “duty” that follows therefrom to “specifically German existence” and its historical destiny in order thereby to introduce into the general course of German existence the energetic but empty movement of existential categories (“to decide for oneself”; “to take stock of oneself in the face of nothingness”; “wanting one’s ownmost destiny”; “to take responsibility for oneself”) and to proceed from there to “destruction” now on the terrain of politics. It is not by chance if one finds in Carl Schmitt a political “decisionism”—in which the “potentiality-for-Being-a-whole” of individual existence is transposed to the “totality” of the authentic state, which is itself always particular—that corresponds to Heidegger’s existentialist philosophy.13

Germanic Being-in-the-World

Heidegger’s rectorship was an ill-fated affair, and he resigned from office after a year. In his official account of his term in office, which was prepared for a university denazification commission in 1945, Heidegger made himself out to be an intrepid foe of the politicization of scholarship. We now know that this explanation is largely a fabrication on his part and that in fact the opposite was the case: as rector, Heidegger proceeded too swiftly in the direction of the politicization of university life. Many members of the faculty were unwilling to follow him in this direction, and controversy ensued. Only when it became clear that Heidegger had failed to gain faculty support for an entire series of radical measures and reforms did he decide to step down.14

Heidegger was never a dyed-in-the-wool Nazi. Instead, he was convinced that Germany’s “National Revolution” needed to be placed on an ontological rather than a biological footing. While he freely embraced arguments for German exceptionalism (that is, for Germany’s singular, world-historical contribution to the history of the West), he never believed that this exceptionalism could be justified in racial or biological terms. For Heidegger, such justifications constituted a regression to the logic of nineteenth-century scientism or biologism. In his view, all questions of human Existenz ultimately stood or fell with the Seinsfrage—the question of Being—and, hence, could only be answered ontologically, never scientifically. Heidegger’s fundamental ontology, in which a rediscovery of the “Greek beginning” played a central role, sought to combat and surmount the previous century’s Darwinian revolution. The “ontological potential” of National Socialism could not, therefore, be explained in evolutionary or Social Darwinist terms. In Heidegger’s view, the racial-biological interpretation of Nazism had succumbed to a self-misunderstanding. Ever the hermeneuticist, Heidegger believed that he understood Nazism better than the Nazis understood themselves. After all, if the ultimate questions of human existence, insofar as they pertained to the manner in which humanity allowed beings to manifest or show themselves, were ontological questions, who would be better placed to pass judgment on a political movement—or at least its standing in relationship to the “history of Being”—than a philosopher? It is in this vein that Heidegger’s “arrogant” remark to Ernst Jünger—that Hitler had let him (Heidegger) down and, hence, owed him an apology—must be understood.15 By this claim, Heidegger meant that it was not he who had erred by entrusting the Nazis with his support; it was Nazism itself that had gone astray by failing to live up to its true philosophical potential.

Despite these philosophical reservations, Heidegger’s identification with the possibilities embodied in the new regime remained profound, as one can see by his May 1933 Rectoral Address, which concludes with an inspired paean to the “Glory and Greatness of the [National] Awakening.”16 However deluded his actions may seem in retrospect, it is clear that Heidegger thought of himself as Plato to Hitler’s Dionysos (the tyrant of Syracuse), and that it was his intention, as a colleague would later remark, to provide the Nazi movement with the proper philosophical direction, and thus “to lead the leader” (den Führer führen).17

Along with the rectoral address, the 1934 lectures on “Logik” are philosophically significant insofar as they reveal how Heidegger understood the essential commonalities between fundamental ontology and the Third Reich. Instead of the biological National Socialism favored by the Nazi party hierarchy, Heidegger became an advocate of what one might call an “ontological National Socialism” or “ontological fascism.” He was convinced that the Nazis’ abrogation of liberal democracy and Germany’s turn toward a one-party dictatorship were positive developments. Like his intellectual compagnons de route, Carl Schmitt and Ernst Jünger, the example of Mussolini’s Italy had convinced him that fascism embodied the historically meaningful alternative to liberalism; it was merely a question of adapting fascist methods and goals to Germany’s unique historical circumstances. That fascism, or a variant thereof, represented the best prospect for overcoming the abyss of European nihilism was a conviction Heidegger retained until the end of his days, despite his apparent postwar apoliticism.18 Even in his later apologias and self-justifications, he never tried to conceal the fact that the Nazi seizure of power was a fundamentally constructive step that, regrettably, failed to live up to its ultimate metaphysical potential. In his view, National Socialism’s empirical shortcomings left its historical “essence” unaffected. It was merely that, as he put it, the Nazis “were far too limited in their thinking” to provide their political revolution with the necessary ontological grounding.19 The “ontological moment,” or Kairos, had been there for the taking; yet, owing to human weakness (a weakness grounded in an inferior, “scientific” ideological perspective), the moment was never seized. As Heidegger remarked in a lecture course during the mid-1930s: “Hitler and Mussolini—who have, each in essentially different ways, introduced a countermovement to nihilism—have both learned from Nietzsche. The authentic metaphysical realm of Nietzsche has not yet, however, been realized.”20 The “countermovement to nihilism” that had been introduced by Hitler and Mussolini—fascism—was one that Heidegger wholeheartedly endorsed. That the two fascist dictators had not yet entered into the “authentic metaphysical realm of Nietzsche” indicated the space that still separated European fascism from the ontological goals that, in Heidegger’s view, should have constituted its raison d’être.

In Heidegger’s “Logik” lecture course, the names of Mussolini and Hitler also figure prominently. Heidegger invoked their achievements in order to illustrate the meaning of “historicity.” For Heidegger, historicity signified authentic historical existence, as opposed to a merely passive and inessential historical Being-at-hand. As such, the concept of historicity bears affinities with Hegel’s conception of “world historical” as well as Nietzsche’s notion of “monumental history,” which the author of The Use and Abuse of History defines as “history in the service of life,” or history as written and lived by the “experienced and superior man.”21

The examples Heidegger employs to illustrate his thesis are telling. Just as in Being and Time the contrast with inauthentic Dasein serves to accentuate the uniqueness of authenticity, in the “Logik” he begins with an analysis of pseudohistorical life.

In the nineteenth century, dominated intellectually by Darwin and Spencer, the concept of natural history gained currency, and misguided attempts arose to subsume human history under this fashionable social evolutionary rubric. But according to Heidegger, though nature evolves, it is devoid of history properly so-called or historicity, which entails a sense of a “mission” and “destiny” (Auftrag and Geschick) to which a people (Volk) must measure up.

For Heidegger, one essential manifestation of the spiritual decline of the West was that the concept of history, in the sense of historicity, had become meaningless. As Heidegger observed, nowadays one recounts the history of capitalism and of the peasant wars; one even discusses the history of the ice age and of mammals. But none of these conceptions allows room for history in the sense of historical Existenz. His argument culminated in the following provocative claim:

[It is said:] Nature, too, has its history. But then Negroes may be said to have history. Or then does nature not have history? It can indeed enter into the past as something passes away, but not everything that passes away enters into history. If an airplane propeller turns, then nothing actually “occurs” [geschieht]. Yet, when the same airplane brings the Führer to Mussolini, then history [Geschichte] occurs. The flight becomes history…. The airplane’s historical character is not determined by the turning of the propeller, but instead by what in the future arises out of this circumstance.22

Despite their sensational side, certain of Heidegger’s positions must be given their due. That there are important differences between natural and human history is self-evident, for in recent years, sociobiology has sought to efface the difference between them. However, the next set of distinctions he proposes—his condescension toward the history of capitalism and peasant wars—is more troubling. The topics themselves cannot be a priori condemned as inauthentic. Instead, the philosopher has prematurely accorded them short shrift.

The fact that Heidegger’s judgments are often presumptuous—e.g., his supercilious contention that “Negroes,” like nature, do not have a history—should not absolve one of the need to hazard judgments about the relative significance of historical events. A slack postmodernist relativism is not the proper antidote to Heidegger’s Eurocentric arrogance. What is troubling about Heidegger’s standpoint is not that he judges but the basis on which he distinguishes. His lock-step identification with the “German ideology” risks settling in advance all questions of relative historical merit. “Capitalism,” “peasant wars,” “Negroes”—once the world has been neatly divided into “historical” and “unhistorical” peoples and events, history’s gray zones fade from view. That the “Volk” that, in Heidegger’s view, possessed “historicity” in the greatest abundance—the Germans—had as of 1934 abolished political pluralism, civil liberties, and the rule of law and was in the process of consolidating one of the most brutal dictatorships of all time, cannot help but raise additional doubts about the “existential” grounds of Heidegger’s discernment. Here, one could reverse the terms and claim that Germany of the 1930s suffered from an excess of historicity. Conversely, the historical events and peoples that Heidegger slights could readily be incorporated into progressive historical narratives.23 That he fails to perceive these prospects is attributable to his renunciation of “cosmopolitan history” and his concomitant embrace of a philosophically embellished version of German particularism or so-called Sonderweg. From an epistemological standpoint, Heidegger’s difficulties derive from his decision to base ethical and political judgments on factical rather than normative terms; that is, from the Jemeinigkeit or concrete particularity of German Existenz.

The more one reconsiders Heidegger’s philosophy of the 1930s, the more one sees that one of its guiding leitmotifs is a refashioning of Western metaphysics in keeping with the demands of the Germanic Dasein.24 He consistently rejects the “universals” that in the Western tradition occupied a position of preeminence in favor of ethnocentric notions derived from the annals of Germanic Being-in-the-world. The example of the airplane that “brings the Führer to Mussolini” is merely a paradigmatic instance of a more general trend.

Logic and Volk

Heidegger’s lectures on “Logic” were held in the aftermath of his failed rectorship. In consequence, they express a political wisdom born of his disillusionment with the Nazi regime. Yet, upon reading them, it is apparent that Heidegger, far from having abandoned his belief in Nazism, is merely interested in propagating an “essentialized” interpretation of the movement’s significance—an interpretation derived from the standpoint of the “history of Being” and the precepts of the philosopher’s own “essential thinking.”

Although the nominal topic of the 1934 lecture course is “logic,” the traditional concerns of formal logic could not be more foreign to Heidegger’s approach: “We want to shake logic to its very foundations,” Heidegger declares. “The power of traditional logic must be broken. That means struggle [Kampf].”25 Thereby, Heidegger signals a concern that had been characteristic of his lectures and writings throughout the 1920s and 1930s: a wish to break with the strictures of academic philosophy and a concomitant desire to rediscover philosophy’s rootedness in human existence, whose ultimate expression, in keeping with the strictures of “historicity,” is the life of the Volk. As he observes at one point: “We do not want a ‘disinterested philosophy’ [Standpunktsfreiheit der Philosophie]; instead, what is at issue is a decision based on a determinate point of view [Standpunktsentscheidung].”26

How is it that Heidegger is able to turn a lecture course on logic into a discourse about the virtues of völkisch Dasein? He is at pains to demonstrate that modern “logic” is a perversion of the Greek “logos.” According to Heidegger, the Greek ideal had very little to do with the notion of propositional truth or the cogency of formal judgments. Such concerns represent Aristotelian accretions and misunderstandings that have been consecrated by the error-ridden Western metaphysical tradition. Heidegger claims that the original meaning of logic concerned language as a “site” for the emergence of Being. Yet Being never reveals itself arbitrarily. Thus, those to whom it exposes itself must be attuned to its “sendings” (Schickungen). In this respect, it goes without saying (at least for Heidegger) that certain peoples are linguistically and historically privileged. Ultimately, therefore, all linguistic questions turn out to be questions of human existence. As Heidegger remarks: “The question concerning the essence of language is not a question of philology or the philosophy of language; instead, it is a need of man insofar as man takes himself seriously.”27 Thus, when posed “essentially,” existential questions also concern the historical self-understanding of a people or Volk. In this way, Heidegger is able to make the transition from logic and language to the hidden potentials of Germany’s National Revolution. By “choosing themselves,” as Heidegger puts it, the Germans are also opting for a new understanding of Being: an understanding that would be free of the divisiveness and debilities of the liberal era and that would finally prove adequate to the fateful “encounter between planetary technology and modern man.”28 Germany’s momentous political transformation of 1933—historicity in the consummate sense—has gone far toward the necessary goal of establishing a unified political will among the German people. As Heidegger comments in the “Logik”: “Insofar as we have become adapted to the demands of the university, and the university adapted to the demands of the state, we [at the university] also want the will of the state. However, the will of the state is the will-to-domination of a Volk over itself. We stand in the Being of the Volk. Our Being-a-Self [Selbstsein] is the Volk.”29

Heidegger thereby advocates a type of intellectual Gleichschaltung. As a long-standing critic of academic freedom and the separation of science from broader existential concerns, in the Nazi revolution Heidegger saw an unprecedented opportunity to reintegrate knowledge with Volk and “state,” thereby compelling it to serve a set of higher ontological goals. Only in this way would knowledge cease to be autonomous and “free-floating” as it was during the liberal era. By standing in the service of a higher “spiritual mission” (geistigen Auftrag) it would, Heidegger believed, regain a dignity and meaning it had not possessed since the Greeks. As Heidegger encourages his student listeners: “The small and narrow ‘we’ of the moment of this lecture has suddenly been transformed into the we of the Volk.”30

A devotion to the precepts of intellectual Gleichschaltung already characterized Heidegger’s radicalism as rector. “The defining principle of my rectorship,” he once declared, “has been the fundamental transformation of scholarly education on the basis of the forces and demands of the National Socialist state.”31 In the “Logik” he complained bitterly that to date university reforms had proved insufficiently radical, that the “dissolution” of the old university structure had not proceeded far enough.32

Heidegger believed that in contemporary Germany, few concepts were more widespread yet poorly understood than the “Volk” idea. He believed that it was his prerogative and calling to undertake a “phenomenological” clarification of its meaning and import. Correspondingly, much of the “Logik” is devoted to this task. According to Heidegger, one of the linguistic and existential confusions of the early days of the Nazi revolution derived from the fact that people invoked the Volk concept in a wide variety of contexts and settings—Volksgemeinschaft, Volkshochschule, Volksgericht, and Volksentscheidung were just a few of its many usages—without a deeper understanding of its essence. It was fundamental ontology’s task to bring clarity and precision to this idea.

In a manner reminiscent of Aristotle, Heidegger proceeds by examining a variety of popular, yet misguided approaches to the question. Frederick the Great, for example, referred to the Volk as “The beast with many tongues and few eyes.” Currently, observes Heidegger, there are those who define the Volk as an “association of men” and others who describe it as an “organism.” Will such definitions suffice for our contemporary historical needs, he inquires with mock seriousness? “Perhaps for reading newspapers,” he skeptically rejoins.33

The nature of the Volk, he continues, can be defined neither sociologically nor scientifically. Echoing his characterization of Dasein in Being and Time, he observes that in interrogating the concept of the Volk, we are concerned not with “what” questions, which would characterize the being of things, but with “who” or “we” questions: that is, with existential questions—questions that address the historical identity of the Germans. “The question: are we the Volk that we are? is far from stupid,” remarks Heidegger.34 As it pertains to the historicity of German Dasein, the question cannot be answered in advance. Its future determination will depend on a “decision” (Entscheidung) of the German people as to whether they can measure up to their vaunted historical mission.

The Estate of Labor

Not all aspects of Heidegger’s discussion of historicity are contaminated by the German ideology. At issue was a “crisis of historical existence” whose reality was widely acknowledged during the interwar period. Heidegger’s 1929 lecture course, The Fundamental Concepts of Metaphysics, is preoccupied with the question of the present age as an age of “affliction” or “destitution.”35 One manifestation of this all-encompassing destitution was a mood of generalized “boredom” (Langweile): a sense of disorientation and inertia, combined with a corresponding lack of will. In Heidegger’s existential idiom, “moods” (Stimmungen), rather than concepts or ideas, are often the defining feature of an age.36 Boredom, and the existential paralysis it entails, is a manifestation of inauthenticity: it breeds a lack of “decisiveness” (Entschlossenheit) and culminates in the conformity of the “they” (das Man).

Yet time and again the conservative revolutionary idiom Heidegger favors slips into a mode of proto-fascist yearning—in part because Heidegger rules out nonradical alternatives as inferior “half-measures” (Halbheiten).37 Moreover, the more closely one examines the idea of historicity, the more apparent is the degree to which philosophical and historical dimensions are fused. A concept that, on first view, seems largely formal, and thus potentially applicable to a variety of historical circumstances, turns out to be inordinately content-laden. Ultimately, Heidegger’s formulation of historicity is irreconcilable with—and formulated explicitly in opposition to—political liberalism as a figure for freedom of conscience, rule of law, and individual rights. Liberalism is the paradigm that Heidegger wishes to surmount insofar as it is the source of our current “destitution.” This is true to the point that it becomes very difficult to separate Heidegger’s critique of “subjectivity” (Descartes and his heirs) from his dubious political conclusions.38

As in Being and Time, the notion of Stimmung or “mood” plays a key role in the “Logik.” Heidegger observes that “the man who acts greatly is defined by moods—by great moods—whereas small men are defined only by temperaments.” “Every great deed of a people [Volk] comes from its foundational mood [Grundstimmung].”39 The rapid slippage between “ontological” and “ontic” levels of analysis is palpable: “The three-fold character of mandate, mission, and labor [Auftrag, Sendung, und Arbeit] is unified through mood,” claims Heidegger. “To experience time by way of our appointed mission [Bestimmung] is the great and unique orientation of our Being qua historical Being. The fundamental nature of occurrence is our appointed mission in its three-fold sense: mandate, mission, and labor.”40

But it is Heidegger’s emphasis on the importance of “labor” (Arbeit) that is the defining feature of his political worldview. During his time as rector, Heidegger ran afoul of his fellow faculty members due his attempt to make participation in “labor camps”—National Socialist sponsored public work projects that included obligatory ideological training—a requirement of university life. To Heidegger’s colleagues, his vigorous endorsement of the camps seemed a lamentable concession to a regime that was both repressive and anti-intellectual. To Heidegger, conversely, their reaction was only a further instance of his colleagues’ insufficient radicalism.41

Both Heidegger’s 1933 rectoral address and his political speeches are fraught with references to the virtues of “labor” and of “labor service.” “The Self-Assertion of the German University,” for example, stresses the paramount importance of three types of service: knowledgeservice, military service, and labor service. During this period, moreover, the notion of the “setting-to-work” (“in-Werk-setzen”) of truth figures prominently in his philosophy. His political addresses of 1933–34 are preoccupied with the question of “labor camps”—the aforementioned Nazi-sponsored public work projects—that were meant to serve as a vehicle for the leveling of class differences as well as National Socialist ideological indoctrination.42 Thus in “Labor Service and the University” Heidegger glorifies the virtues of “labor” in an existential idiom that is only a step removed from the Storm Trooper ethos convulsing Germany: “A new institution for the direct revelation of the Volksgemeinschaft is being realized in the work camp,” declares Heidegger. “In the future, young Germans will be governed by the knowledge of labor, in which the Volk concentrates its strength in order to experience the hardness of its existence, to preserve the momentum of its will, and to learn anew the value of its manifold abilities.” And in his 1934 speech, “National Socialist Education,” he seeks to differentiate National Socialism’s “spiritual” conception of labor from the outmoded and vulgar Marxist understanding of the term:

Like these words “knowledge” and “Wissenschaft,” the words “worker” and “work,” too, have a transformed meaning and a new sound. The “worker” is not, as Marxism claimed, a mere object of exploitation. Workers [Arbeiterstand] are not the class of the disinherited who are rallying for the general class struggle…. For us, “work” is the title of every well-ordered action that is borne by the responsibility of the individual, the group, and the State and which is thus of service to the Volk.43

The labor camps praised by Heidegger, which were administered by the Reichsarbeitfront, were a linchpin in the Nazi plan for a homogeneous Volksgemeinschaft. In November 1933, under the direction of Albert Speer, the Nazis established an office for the “Beautification of Labor” as an offshoot of the “Strength Through Joy” leisure bureau—a fact that helps one appreciate the centrality of labor in the National Socialist worldview. Of course, one of the distinguishing features of Nazi rule was its grandiose efforts to secure aesthetic self-legitimation, the likes of which had not been seen since the age of absolutism, and the “Beautification of Labor” program represented an essential component of these efforts. Often, these beautification efforts were related to matters of efficiency, as in the slogan, “Good light, good work.” As Anson Rabinbach has noted, “By combining industrial psychology with a technocratic aesthetic that glorified machinery and the efficiency of the modern plant, Beauty of Labor signified a new dimension of Nazi ideology.”44 But like so many other aspects of Nazism that targeted the working class, the program was long on form and short on substance. Thus, although lip service was paid to the “estate of labor,” the traditional capitalist hierarchy between management and labor was rigidly maintained. German workers may, in certain instances, have enjoyed slightly improved working conditions. But in almost every substantive respect (wages, benefits, living conditions, and so forth), their lot under the Nazis failed to improve. Instead, the mostly cosmetic improvements were intended to facilitate their ideological integration within the Nazi behemoth. Although the “Beautification of Labor” program claimed that it sought to restore the “spiritual dignity” of work that was lacking under capitalism and communism, it entailed few real benefits for labor itself.

One historian has summarized the pivotal ideological function of “labor” in the early years of the Third Reich in the following terms:

As a supplement, almost as a substitute for a labor policy, the Third Reich offered a labor ideology, combining simultaneous and roughly equal appeals to the pride, patriotism, idealism, enlightened self-interest, and, finally, urge to self-aggrandizement of those exposed to it. The centerpiece was the labor ethos, focusing not so much on the worker as on work itself. “Work ennobles” was a characteristic slogan… Large factories even erected chapels whose main aisle led to a Hitler bust beneath the symbol of the Labor Front, flanked by heroic-sized worker figures; in effect, little temples to the National Socialist god of work.45

Heidegger’s concern with the importance of labor in the new Reich was a matter of philosophical as well as political conviction. A longtime critic of the senescence and disorientation of German university life, he was of the opinion that the labor camps would serve to reintegrate knowledge with the life of the German Volk, whose simplicity and lack of sophistication he revered.46 As Löwith remarked, Heidegger “failed to notice the destructive radicalism of the whole [Nazi] movement and the petty bourgeois character of all its ‘strength-through-joy’ institutions, because he was a radical petty bourgeois himself.”47 Heidegger, who hailed from the provincial lower classes, and who, despite his manifest brilliance, was denied a university chair until the age of thirty-nine, found much he could agree with in Nazism’s dismantling of the old estates and commitment to upward social mobility.48 In his view, the value of labor camps as a vehicle of ideological reeducation for politically reticent scholars could hardly be overestimated.

Heidegger’s commitment to the goals of labor service may also be traced to the influences of conservative revolutionary ideology. Since Germany’s defeat in World War I, which was abetted by class divisions as well as revolutionary upheaval during the war’s final months, it had become a commonplace among radical conservatives that, in the future, the working classes must be integrated within the “national community.” One of the classical expressions of this new orientation was Oswald Spengler’s 1919 tract, Prussianism and Socialism. With the war effort’s nationalization of the economy fresh in mind, Spengler argued that the virtues of Prussian nationalism must be combined with the economic advantages of “socialism,” which he understood in terms of the étatiste ideal of a state-directed or planned economy. Only in this way could Germany secure the internal unity necessary for success in the next European war. As Spengler observes:

We need a class of socialist supermen…. Socialism means: power, power and ever more power…. The way to power is foreordained: to combine the valuable part of German workers with the best representatives of the old Prussian devotion to state—both resolved to found a rigorously socialist state … both forged into unity through a sense of duty, through the consciousness of a great task, through the will to belong, in order to dominate, to die, and to triumph.49

During the early 1930s Heidegger had also fallen under the political influence of Ernst Jünger, whose 1932 study, The Worker (Der Arbeiter), had been an immense success in right-radical circles. In The Worker, Jünger outlined a theory of a future totalitarian state. In it, the debilitating divisions of political liberalism would be surmounted. For Jünger, too, the “total mobilization” that marked the final stages of the German war effort during World War I—the fact that all aspects of economic, cultural, and domestic life were placed on common footing for the sake of a shared military goal—had set a significant precedent. Under conditions of the total state, argued Jünger, where geopolitical conflicts determined domestic political ends, the distinction between “soldiers” and “workers” would be effaced. Both groups would merely represent different aspects of a wholly militarized society. Jünger’s dronelike “soldier-workers” represented an ideological antithesis to the timorous “bourgeois,” concerned only with effete pursuits such as personal security and well-being. His idealized portrait of militarized “work-world” left a profound impression on Heidegger, who offered two seminars on Jünger during the 1930s, and who later avowed that during this period his understanding of politics had been predominantly shaped by Jünger’s 1932 treatise.50

Germany’s difficulties in adapting to the challenges of modern industrial society—which represented the antithesis of everything that it, qua Kulturnation, had stood for historically—are legendary. Following the traumas of war, defeat, and revolution, the mandarin intellegentsia, convinced of industrialism’s inevitability, sought a way to reconcile traditional German values (Spengler’s “Prussianism”) with the imperatives of twentieth-century economic life. Heidegger alluded to this dilemma when he characterized National Socialism’s “inner truth and greatness” as a solution to the fateful “encounter between planetary technology and modern man.”51 In The Will to Power—a radical conservative Bible—Nietzsche had already posed the problem of how one could maintain the values of heroism and cultural greatness in an era where qualitative differences were increasingly leveled by the dictates and rhythms of the machine. “In opposition to this dwarfing and adaptation of man to a specialized utility, a reverse movement is needed—the production of a synthetic, summarizing, justifying man for whose existence this transformation of mankind into a machine is a precondition, as a base on which he can invent his higher form of being.”52 For Nietzsche, the attainment of “great politics” did not mean a return to an idyllic, premodern past; it required reconciling the needs of the superman with the realities of modern technology. A few paragraphs later, Nietzsche issued his call for the “barbarians of the twentieth century”: “A dominant race can grow up only out of violent and terrible beginnings. Problem: where are the barbarians of the twentieth century?” In National Socialism, his prophetic summons found an adequate response.53

From 1936 to 1940, Heidegger offered four lecture courses on Nietzsche’s philosophy in which he demonstrated that he had internalized the lessons of conservative revolutionary theory of technology (Technikgedanke). As he observes in his 1940 course “European Nihilism”:

What Nietzsche already knew metaphysically now becomes clear: that in its absolute form the modern “machine economy,” the machine-based reckoning of all activity and planning, demands a new kind of man who surpasses man as he has been hitherto…. What is needed is a form of mankind that is from top to bottom equal to the unique fundamental essence of modern technology and its metaphysical truth; that is to say, that lets itself be entirely dominated by the essence of technology precisely in order to steer and deploy individual technological processes and possibilities. The superman alone is adequate to an absolute “machine economy,” and vice versa: he needs it for the institution of absolute domination over the earth.54

Toward the end of the same course, and with Germany’s stunning Blitzkrieg victories fresh in mind, Heidegger provided further evidence that the Nazi war machine embodied the “form of mankind equal to modern technology and its metaphysical truth.” It would be a fateful misunderstanding of Germany’s glorious battlefield triumphs, notes Heidegger, to construe the Blitzkrieg strategy (“the total ‘motorization’ of the Wehrmacht”) as an instance of “unlimited ‘technicism’ and ‘materialism’”—that is, as developments on a par with the West’s employment of technology. “In reality,” insists Heidegger, “this is a metaphysical act.”55 The Wehrmacht’s stunning success proved that Germany alone had mastered the challenge posed by “planetary technology to modern man.” Whatever Heidegger’s philosophical differences with regime ideologues may have been at this point, he was convinced that Nazi Germany had gone far toward realizing the “dominion and form” (Herrschaft and Gestalt) of “the worker” as forecast by Jünger’s prophetic 1932 essay.

In Being and Time, the instances of labor cited by Heidegger all pertained to the traditional work-world of artisans and handicraft. His diagnosis of the times had been resolutely anti-modern. By 1933, however, under the twin influences of Jünger and Germany’s National Awakening, Heidegger’s attitude toward technology underwent a decisive shift. In his view, the Germans—the most metaphysical of peoples since the Greeks—by allowing themselves to be entirely dominated by the “machine-economy,” were well on their way to establishing their “absolute domination over the earth.”

Labor and Authenticity

For decades, the themes of technology and labor had been scorned by Germany’s intellectual mandarins. They were, at best, socialist concerns, beneath the dignity of sophisticated Kulturmenschen. Along with his fellow conservative revolutionaries, however, Heidegger was convinced that, to paraphrase Walther Rathenau, “economics had become destiny.” Those who ignored this ultimatum of twentieth-century life did so at their own peril.

This insight helps account for Heidegger’s abiding preoccupation with the concept of “work” during this period. Heidegger’s focus on the importance of work led him to flirt with themes and concerns that had previously been the province of socialist thinkers. Ultimately, of course, his perspective remained rigorously völkisch, and it is in this sense that his attraction to Nazism as a form of national socialism must be understood.56

Heidegger’s discussion of the ontological vocation of work is of considerable philosophical import. Significantly, he treats it in relationship to the problem of “temporality,” one of fundamental ontology’s central themes. In Being and Time, Heidegger criticized the modern concept of time, derived from the natural sciences and subsequently canonized by Descartes, as radically deficient. According to this conception, even human existence was understood on the model of “things,” that is, as an inanimate “entity” that was merely “present-at-hand” (vorhanden).

In the “Logik” Heidegger polemicizes against modernity’s inferior understanding of temporality, which is governed by an “empty” concept of time. Time “has become an empty form, a continuum that is alienated from the Being of man,” Heidegger protests.57 Whereas in 1927 the idea of authentic temporality was linked to the notion of Being-toward-death, in the “Logic,” authentic temporality is tied to the concept of work. Along with “mandate” and “mission,” work is an essential component of the “foundational mood” (Grundstimmung) of the German Volk. In the context at hand, what stands out is his quasi-Marxist characterization of work as an indispensable manifestation of authentic selfhood. “Time belongs characteristically and solely to man,” observes Heidegger:

According to the vital conception of time as our ownmost event, natural processes merely “expire” within the framework of time; but, stones, animals, and plants are not temporal in the sense that we are. They do not dispose over a concept of mission, they accept no mandate, and they do not work. Not for lack of concern, but instead because they are incapable of work. The horse is only engaged in a human work-event. Machines, too, do not work. Work, understood in the physicalist sense, is a misunderstanding of the nineteenth century.58

In Being and Time, Heidegger’s discussion of authenticity culminates in the concept of historicity. At issue is the idea of an authentic collectivity: a Volk or community that is capable of measuring up to its appointed historical destiny (Geschick).59 It is by “historicizing” its existence that a Volk acts according to the strictures of authentic temporality. Here, we are reminded of Heidegger’s contention in the “Logik” that not all peoples are capable of having “history”—that is, “history” conceived according to the requirements of authentic historicity.

What is new in the “Logik” is that for the first time Heidegger systematically ties both temporality and historicity to the concept of work. Work is thereby treated as an essential modality whereby humanity realizes itself historically. By considering work as an expression of authenticity, Heidegger approximates the early Marx’s expressivist concept of labor in the Paris Manuscripts. Under the influence of Hegel and Schiller, Marx regarded labor as the highest expression of man’s “species being.” In this regard, it is hardly coincidental that a critique of “alienated labor” became the basis for his youthful critique of capitalism’s degradation of everyday life.

Heidegger approximates the same expressivist concept of labor when he characterizes modern temporality, whose foremost expression is “work,” as “alienated from the Being of man.” Nevertheless, the Hegelian-Marxist, utopian ideal of a “reconciliation” between man and nature—in the Paris Manuscripts, Marx fantasizes about the eventual “humanization of nature and the naturalization of man”—is foreign to Heidegger’s neo-Kierkegaardian, existential sensibility. Such utopian dreams, moreover, are fundamentally alien to the post-Spenglerian, apocalyptical “mood” that Existenzphilosophie consciously cultivates.

In an apologia written after the war for Freiburg University denazification proceedings, Heidegger explained that he became disillusioned with Nazism following the June 30, 1934, purge of the Röhm faction.60 For Heidegger, the Röhm purge symbolized (as it did for many “old fighters”) a “right turn” on the part of the new regime. It signaled an abandonment of the älte Kämpfer—many of whom upheld the “socialist” ideals of National Socialism—and an accommodation with traditional German elites: Hindenburg, the Wehrmacht, big industry. As such, Heidegger’s avowal is a further indication of the depth of his commitment to the ouvrièriste wing of National Socialism in its early phase.

Since the “Logik” is a lecture course, rather than a public political statement (which might necessitate certain compromises with the regime), it presumably reflects Heidegger’s genuine views. That is why it is so disturbing to find him, at least in one instance, flirting with the regime’s racial-biological doctrines. Equally disturbing is the fact that Heidegger suggests that one might reconcile Nazism’s racial precepts (the concepts of “blood” and “racial descent”) with his own pet existential themes and ideals of “mood,” “work,” and “historicity”:

Blood, racial descent (das Geblüt) can only be [reconciled] with the foundational mood of man when it is determined by temperament and mood [das Gemüt]. The contribution of blood comes from the foundational mood of man and belongs to the determination of our Dasein through work. Work = the historical present. The present (die Gegenwart) is not merely the now; instead it is the present insofar as it transposes our Being in the emancipation of existence that is accomplished through work. As someone who works man is transported into the publicness of existence. Such being-transported belongs to the essence of our Being: that is, to our being-transported amid things in the world…. As something original, existence never reveals itself to us via the scientific cognition of objects, but instead in the essential moods that flourish in work and in the historical vocation of a Volk that predetermines all else.61

One of the Nazis’ major domestic political concerns in the regime’s initial years was whether they would be successful in integrating the German working classes—traditionally, staunch supporters of the political left—within the National Socialist Volksgemeinschaft. To that end, they established the German Labor Front to assure German workers that their role in the new state was an indispensable one. Both the “Strength through Joy” and “Beautification of Labor” programs discussed earlier were an offshoot of the same effort.62 In his celebration of the “joy of work” (Arbeitsfreudigkeit), Heidegger once again demonstrates the elective affinities between Existenzphilosophie and the National Socialist worldview:

The question of the joy of work is important. As a foundational mood, joy is the basis of the possibility of authentic work. In work as something present, the making present of Being occurs. Work is presencing in the original sense to the extent that we insert ourselves in the preponderance of Being; through work we attain the whole of Being in all its greatness, on the basis of the great moods of wonder and reverence, and thereby enhance it in its greatness.63

However, Heidegger’s encomium to the “joys of work” contains a hidden political agenda. Critics had frequently argued that the world-view expressed in Being and Time was excessively lachrymose. As evidence of the work’s overriding mournfulness, detractors frequently invoked Heidegger’s preoccupation with categories such as “Angst,” “Being-toward-death,” “Guilt,” and “Falling.” Indeed, much of Heidegger’s existential ontology was indebted to a secularized Protestant sensibility that stressed the insurmountability of original sin and the irremediable forlornness of the human condition. In place of the Counter-Reformation deus absconditus, Heidegger substituted Nietzsche’s declaration concerning the “death of God.” But in the last analysis, the predominant view of the human condition was the same. Herbert Marcuse alluded to this problem when, in a 1971 interview, he remarked:

If you look at [Heidegger’s] view of human existence, of Being-in-the-world, you will find a highly repressive, highly oppressive interpretation. I have just gone through the table of contents of Being and Time and had a look at the main categories in which he sees the essential characteristics of existence or Dasein. I can just read them to you and you will see what I mean: Idle talk, curiosity, ambiguity, falling and Being-thrown, concern, Being-toward-Death, anxiety, dread, boredom, and so on. Now this gives a picture which plays well on the fears and frustrations of men and women in a repressive society—a joyless existence: overshadowed by death and anxiety; human material for the authoritarian personality.64

The disconsolate worldview presented in Being and Time proved difficult to reconcile with the groundswell of enthusiasm that had been unleashed by Germany’s National Awakening. By celebrating the “joy of work,” Heidegger took steps to ensure the essential compatibility between fundamental ontology and the National Revolution.

Labor As Unconcealment

The “Logik” lectures contain many aspects that are frankly ideological; but it would be misleading to erect a firewall between Heidegger’s ideological writings (the rectoral address and more narrowly political texts) and his more philosophical works. Such rigid distinctions between philosophy and ideology prove untenable. Although it may be tempting to downplay the significance of the “Logik” owing to the prominence of political references and elements, a close examination of other contemporary texts reveal merely differences in degree rather than differences in kind.

Moreover, the philosophically significant dimensions of the “Logik” build organically on the ontological foundations established in Being and Time. There is no absolute break between the two texts. Instead, Heidegger attempts, as he always did, to elaborate fundamental concepts in light of new developments that are both historical and conceptual in nature. The National Awakening of 1933 is certainly one such development of whose “epochal” nature Heidegger was convinced. At the same time, in the “Logik,” he was engaged in a process of redefining the basic terms of his philosophy, as was the case throughout his productive life.

For this reason, his discussion of the concept of labor in the “Logik” lectures is of genuine philosophical significance. Although the concept appears nowhere in Being and Time, it figures prominently in “The Self-Assertion of the German University.” There, under the guise of “labor service,” it appears (along with “military service” and “service in knowledge”) as one of the three essential modes of comportment required by the new Reich.

In Being and Time, Heidegger is at pains to identify the fundamental existential structures (Existenzialien) through which Being is revealed to human experience. He considers the history of Western thought to be largely unserviceable in this regard, due to its intellectualist and rationalistic biases. Already Aristotle had defined the vocation of man as animal rationale. Subsequently, via the latinization of Greek thought and culture, this standpoint was disseminated throughout the European world, reaching a culmination of sorts with Descartes’ definition of the distinctively human as res cogitans: the “subject” qua disembodied mind. In opposition to this rationalistic strain, Heidegger sought to redefine human existence as “Dasein” (there-being): a mode of Being-in-the-world that is not in the first instance characterized by intellectual characteristics and habitudes, but by a series of more “primordial” capacities—moods, dealings with tools, Being-with-others, and so forth.

In Being and Time, the discussion of “tools” as a mode of Being “ready-to-hand” (Zuhandenheit) anticipates the status of “labor” in the “Logik.” Heidegger’s point is to show that our experience with useful objects, such as tools, is prior to our conceptualization of objects as mere things toward which we might assume a scientific or objectivating attitude (along the lines of Descartes’ physicalist characterization of objects—including the human body—as res extensa or extended substance). Instead, in our dealings with tools, at issue is a context of relationships that remains implicit and unthematized unless something is amiss: if the head falls off the hammer we are using, its unique and explicit nature as an individual object becomes apparent to us in a way it never was when we were preoccupied with the hammer as an object of use. More generally, our relationship to the hammer and the whole context of relationships it entails (other tools, co-workers, questions of building and dwelling, and so forth) is an essential mode via which Dasein’s Being-in-the-world is constituted and disclosed. This context of relationships tells us something essential about the ontological nature of Dasein—why, for example, Dasein’s Being-in-the-world is different from the Being of things, tools, etc. Without the word ever being explicitly mentioned, the entire discussion, which is a significant one, concerns the status of work in relationship to the Being-in-the-world of Dasein.

Something similar may be said about the status of labor in the “Logik” lectures. Yet, whereas in Being and Time “work” stands for a type of implicit knowledge or phenomenological precondition of human experience, in the “Logik” Heidegger elevates labor to an autonomous and central role in the uncovering of Being. In the “Logik,” Heidegger exalts labor as a type of heroic ontological engagement that, in Being and Time, seemed reserved for “resolve” (Entschlossenheit) and Being-toward-death. His panegyrics to the ontological mission of labor aim to kill two birds with one stone: he seeks to surmount the customary dualism of intellectual and manual labor (another weighty bit of Cartesian detritus) and to demonstrate that the project of fundamental ontology is compatible with the worldview of the new regime—it is the philosophical or serious side of the National Revolution. During the 1930s, Heidegger often praised the essential role played by philosophers, statesmen, and poets in unveiling the truth of Being.65 In the “Logik” lectures, he throws labor into the mix as a way of offsetting the sterile rationalism of traditional philosophy. Thus, just as he had shown in Being and Time how everyday Being-in-the-world is fraught with ontological implications, he seeks to demonstrate in the “Logik” that labor, far from representing an inferior mode of human Being-in-the-world, is an essential modality via which Being is revealed. In fact, in many respects the interventions of labor prove superior to the barren intellectualism characteristic of university scholarship, whose deficiencies Heidegger parodies in his Rectoral Address and elsewhere. As a modality of Being-in-the-world and as a creative approach to nonhuman being, labor transcends the objectivating standpoint of the natural sciences, according to which beings are merely objects of technical mastery cum exploitation. In unreflectively adopting the standpoint of the Cartesian “subject,” modern philosophy has merely perpetuated ad nauseum this Cartesian original sin, resulting in the horrors of modern technology (das Gestell). For Heidegger, conversely, labor is ontologically significant insofar as, unlike “technology” qua “enframing,” it is capable of elevating rather than degrading the otherwise inert “Being of beings.” As he expresses this thought in the “Logik”:

The Being of beings is not exhausted in the Being of objects. Such an erroneous view could only prosper—indeed, it must—where things are from the outset approached as “objects,” a standpoint that presupposes the concept of man as “subject.” Beings however never reveal themselves primordially via the scientific cognition of objects, but in the labor that flourishes in essential moods and in the historical mission of a Volk that determines them.66

To this end, the concept of “socialism” must be taken seriously, claims Heidegger. Not, however, in the customary senses of transforming economic relations or a diffuse interest in collective well-being. Instead, in Heidegger’s view, socialism, when properly conceived, mandates the principle of “hierarchy according to career and achievement, and the inviolable honor of every [type of] labor.”67 At issue is not a Marxian socialism, but a national socialism.