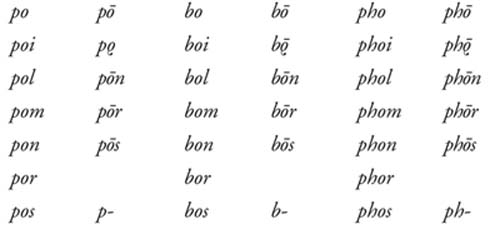

(remember

(remember  , polo, on page 36) can represent at least 15 different Greek syllables:

, polo, on page 36) can represent at least 15 different Greek syllables:‘Not quite the Greek you taught me, I’m afraid!’

Inscription by Michael Ventris on his first post-decipherment publication sent to his former classics master, autumn 1953

‘I’m spending most of my time scrubbing floors at the new house at the moment’, Ventris told Chadwick at the end of August 1953. Three weeks later he, Lois and their two young children Nikki and Tessa, taking their Breuer furniture with them, moved into 19 North End, the modest but well-built house he had designed in the spring and summer of 1952 in a leafy private corner of Hampstead, just off the Heath. The long years at Highpoint – with their mixed memories of school holidays, his late mother Dorothea, the war, marriage, student years as an architect, and endless poring over Linear B until he finally ‘cracked’ it – were over. A fresh phase was beginning in his life, both personally and with regard to the decipherment.

‘Evidence for Greek dialect in the Mycenaean archives’, written with Chadwick in late 1952, had just been published by the Journal of Hellenic Studies. Of course, a lot had happened in the nine months since the joint article was submitted in November, but this was the first solid scholarly exposition of the decipherment to appear in print and there was a rush for it among classicists and others – so much so that the paper was reprinted as a separate pamphlet and sold more than a thousand copies. Also, the hundreds of new tablets excavated by Blegen at Pylos in 1952, and a rather smaller number discovered by Wace at Mycenae, were about to become available for scrutiny (until now Ventris had seen only the celebrated ‘tripods’ tablet sent by Blegen in May). These tablets were virgin material, quite unknown pre-decipherment. Therefore they ought to provide an excellent check on the validity of Ventris’s phonetic values. Now the third and last phase of the decipherment, following the analysis phase (up to June 1952) and the substitution phase (June 1952 to mid-1953), could begin in earnest.

In the intellectual world, the ultimate test of an idea’s worth and the measure of one’s success in proposing it, is that professionals respond and begin to include the idea in their work – whether by incorporating it, rejecting it, or, more usually, by modifying it through sympathy mixed with scepticism. (Naturally credit is not always given to the original source!) From the middle of 1953 onwards, this was indeed the case with the Ventris decipherment. Scholars interested in the early Aegean scripts from across Europe and the United States quickly started to read Linear B. The overwhelming majority agreed that the script wrote a form of early Greek; but there was serious disagreement about how to interpret particular inscriptions. There were also various cranks and, as ever in archaeological decipherment, it was not always simple to discern who the cranks were. ‘After the Times article I had a letter from a crank, enclosed’, Ventris told Chadwick in July. ‘I thought the only way to see what he was up to was to try him out on the TRIPODS. And a pretty good hash it is; I’ve now broken off the engagement. The trouble is that, ridiculous as his ideas are, one always has the uneasy feeling of “there, but for the grace of God…”; and one’s worst nightmare is that one has oneself been a victim of a similar delusion.’ Being an ‘amateur’, Ventris was quite sensitive on the point.

He was wryly amused by the nationalist slant of some reactions. A well-known Greek scholar wrote (in Ventris’s translation): ‘We Greeks owe many thanks to the foreign scholars who have applied themselves with remarkable devotion to the laborious work of solving the riddle of the script and language, in which are written the age-old records of our ancestors found in the sacred soil of our Fatherland.’ While a Russian (again translated by Ventris) commented: ‘The data from the Pylos and Knossos tablets completely support the interpretation followed by Soviet science of the slave-based character of Cretan and Mycenaean society…and once again refute the modernizing prejudices still present in the works of many bourgeois historians.’

It is never easy to define the point at which a script can be said to be ‘deciphered’. Even with Egyptian hieroglyphic, there are words and passages which are almost totally obscure. When Linda Schele, a key figure in the Maya decipherment, was asked how much of the Mayan glyphs had been deciphered, she would always answer that it depended what you meant by ‘deciphered’. In 1993, a few years before her early death, she wrote: ‘Some glyphs can be translated exactly; we know the original word or its syllabic value. For other glyphs, we have the meaning (for example, we have evidence that a glyph means “to hold or grasp”), but we do not yet know the Mayan words. There are other glyphs for which we know the general meaning, but we haven’t found the original word; for example, we may know it involves war, marriage, or perhaps that the event always occurs before age 13, but we cannot associate the glyph with a precise action. For others, we can only recover their syntactical function; for example, we may know a glyph occurs in the position of a verb, but we have no other information. To me the most frustrating state is to have a glyph with known phonetic signs, so that we can pronounce the glyph, but we cannot find the word in any of the Mayan languages. If a glyph is unique or occurs in only a few texts, we have little chance of translating it.’

Linear B suffers from similar difficulties, although it is definitely more fully deciphered than the Mayan script. Right from the start, there have been accusations that the spelling rules are so loose that Linear B sign groups can be manipulated to produce Greek words that in reality are not present in the tablets. As Ventris told Patrick Hunter, his former classics teacher at Stowe, when sending him a copy of his joint paper with Chadwick: ‘Not quite the Greek you taught me, I’m afraid!’ – a fine example of his exquisite, gentle irony.

To Bennett, at the same time he pointed out that in the Cypriot script the sign  (remember

(remember  , polo, on page 36) can represent at least 15 different Greek syllables:

, polo, on page 36) can represent at least 15 different Greek syllables:

| po | bo | pho |

| pon- | bon- | phon- |

| pom- | bom- | phom- |

| pō | bō | phō |

| p- | b- | ph- |

Whereas in Linear B, he said, we might be faced with at least 39 alternatives ( is the Greek iota):

is the Greek iota):

– each of which might be prefixed with an initial -s.

To explain the situation to outsiders – and at the many lectures he was now being asked to give – Ventris made a ‘toy’ out of cardboard (rather reminiscent of his simple model of a ‘grid’ which hung on the wall at Highpoint). It consisted of a box with little windows through which one could slide paper strips. Each movable strip corresponded to one Linear B syllabic sign and listed all its possible transliterations (written in Greek letters, rather than in roman script as above). The strips could then be slid up and down or inserted in the windows in a different order so as to create all possible spelling permutations of a given set of syllabic signs. Ventris added a sketch for Bennett’s benefit, showing the four signs  thought to spell the Greek word ‘tiripod(e)’, as featured in the famous ‘tripods’ tablet P641:

thought to spell the Greek word ‘tiripod(e)’, as featured in the famous ‘tripods’ tablet P641:

(Bennett, as a former wartime cryptographer, replied: ‘I may try to make one of your toys. They are just the sort of thing I used to play with for the army so I will feel right at home.’)

Soon, Bennett went to Greece in order to make drawings of the Pylos tablets discovered in 1952. From Athens he wrote ruefully, and perhaps a shade mischievously, to Ventris: ‘I don’t seem to invent inserted letters very easily or notice parallels in Greek, so that I will gladly let you do that end in time.’ Back in England, Ventris and Chadwick waited anxiously. In December, Bennett generously mailed a partial set of drawings to Ventris, adding: ‘I hope these will be of some use to you, and even more that you can enlighten me on them.… Once one starts putting values in the texts and looking up etymologies it is very hard to know when to stop. I have probably stayed too long on the other end of the job, but it also has to be done.’

The two collaborators decided on an experiment to test the validity of the decipherment. They would each, independently of the other, write detailed interpretations of the virgin Pylos tablets and mail them separately to Bennett in Athens. Only after doing so would they compare notes. Something similar had been attempted in 1857 (though neither Ventris nor Chadwick seems to have been conscious of the comparison), when four ‘rival’ scholars of cuneiform were asked by the Royal Asiatic Society to submit independent translations of a newly discovered inscription; this produced useful results at the early stage of the decipherment of Babylonian cuneiform.

In late January, Ventris fired off his interpretations: 29 closely typed pages minutely inscribed with Linear B in his trademark handwriting. Chadwick did the same, telling Bennett: ‘I expect you will have some good laughs when you come to compare the different versions.’ But the American scholar seems to have been stunned into silence by these two linguistic salvoes from England, contenting himself with a heartfelt thank you to Ventris for clarifying one particular sign group at long distance: ‘I’d not have seen it otherwise.’ The surface of the tablet in question was too damaged to identify the signs with any certainty, but Ventris’s suggested reading, based on the meaning of the surrounding signs as read using his phonetic values, had led Bennett to ‘see’ what his eyes would otherwise have missed. In a way, it was an apt response from this ace epigrapher who was no great linguist. Observation had been suggested by theory, rather than the other way around, as happens quite often in science; for example in astronomy, the planet Pluto was first observed after its existence had been deduced from an analysis of perturbations in the orbit of Uranus and Neptune.

When Ventris and Chadwick eventually got together at North End for the weekend, they too were fairly satisfied. Their twin analyses of the new Pylos tablets shared much common ground. But they were also uneasily aware that there were considerable differences between their two interpretations. Plainly the decipherment still had a long way to go.

At this point, in early 1954, a sizeable group of British classicists clambered on board the Linear B bandwagon, with varying degrees of confidence. Leonard Palmer, the professor of classical philology at Oxford, was perhaps the cleverest of them; and he made sure that everyone knew it. He and Chadwick enjoyed a prickly relationship, in which Professor Palmer liked to refer ostentatiously to Mr Chadwick. There seems little doubt that in Palmer’s view, ‘Ventris and Palmer’ would have been the appropriate combination for the history books, rather than Ventris and Chadwick. While there is no question that Palmer accepted the fundamental correctness of the decipherment and hugely admired Ventris personally, despite the architect’s un-Oxonian diffidence, he would nevertheless be severely critical of some of his interpretations (while implying that the blame for these probably lay with Chadwick!).

A pioneering ‘Minoan Linear B Seminar’ was established at the newly founded Institute of Classical Studies in London, with the enthusiastic advocacy of a professor of Greek at University College, Tom Webster. Ventris agreed to lead the discussion at the first meeting in January and later gave a lecture which was attended by the king of Sweden; in fact he attended the regular seminars many times until the end of 1955. The finest classical scholars of the day came and lectured, and debated matters such as whether the Linear B sign group read as po-ni-ke referred to the fabulous phoenix bird or to the palm tree (both of which share the same spelling in classical Greek), and whether Homer had actually seen a ‘depas’ (cup) of the kind that only King Nestor could lift when it was full, or merely imagined it. Some of the arguments became very heated, but as a student participant, Ian Martin, recalled: ‘Amidst the clash of conflicting egos, the one man without whose vision, insight, and determination not one single one of us would have been there, remained for the most part firmly silent.’

Ventris’s reticence at the London seminars was generally construed as modesty, which was true enough. But he was also sensible to the need to keep his mouth shut. Before the seminar got going, he wrote to Chadwick: ‘I feel these chaps may not realize what comparatively sterile and limited documents we’ve got; and I don’t want our…book on the subject to be written by a dirty great committee! So I will tread cautiously.’ A few months later, he told Bennett: ‘Chadwick and I have not sold our souls to the Institute of Classical Studies in any way, or shown them any unpublished tablets.’

He and his idea were becoming public property, whether he liked it or not. Before the beginning of the seminar, Ventris had been made an honorary research associate at University College; now the University of Uppsala (the oldest university in northern Europe) conferred an honorary doctorate on him at the age of 31; the following year, he would receive an OBE from the Queen. There were also articles about him and Linear B in Scientific American, Time magazine, the New York Times, and many other lesser magazines and newspapers. The Time interview went well, Ventris told Chadwick, but there was less comprehension from the science correspondent of the New York Times: ‘as his own field was wasps, some of the talk about ideograms etc. was a bit difficult. “Was Mycenia a big country” etc…’. Another New York Times article published at this time alleged, rather ludicrously, a link between certain signs at Stonehenge and ‘the recently decoded Minoan syllabary’. It reported that ‘At a working height of four feet from the ground, the architect left behind his mark, the axes and the dagger sign.’ Someone – maybe Ventris himself – has written wittily in the margin of the copy of the article preserved in Ventris’s papers: ‘How clever of Tessa to reach that high!’ (Tessa Ventris was then an eight-year-old.)

In June, Ventris decided that the time was ripe to get started on the big joint book for scholars that he had been discussing with Chadwick since the previous year. ‘I don’t much want to write the “popular decipherment” kind of book, though a section of it must deal with methods’, he told him in a letter from Athens. Several publishers were interested; Ventris and Chadwick soon settled on Cambridge University Press, as recommended by Chadwick.

Documents in Mycenaean Greek, as the book was finally titled, is something of a bible of Linear B studies, consisting of five introductory chapters on the decipherment itself and what it has revealed about the Mycenaean writing system, language, personal names and society, followed by the detailed interpretation of 300 Linear B tablets grouped into chapters such as ‘Livestock and agricultural produce’ and ‘Textiles, vessels and furniture’, and an extensive glossary of Mycenaean words. There is also a long foreword by Wace, the excavator of Mycenae and professor of classical archaeology at Cambridge who had been the chief victim in the 1920s of Sir Arthur Evans’s Minoan ‘imperialism’ and was therefore delighted by the evidence of the tablets.

Ventris decided on the original scheme of the book, then he and Chadwick divided between them the writing of particular chapters. Drafts of these were exchanged and criticized by each other. Sometimes this led to material being completely scrapped, but on the whole the drafts became the framework onto which bits were then fitted by the other writer. ‘It’s impossible to read the book now and say “That is Ventris and that is Chadwick”,’ remarked Chadwick in the 1980s in Michael Ventris Remembered, after producing his second edition of Documents in 1973. ‘There are certain people’ – he was thinking of Palmer among others – ‘who have since said that everything that’s right in the book is Ventris’s and everything that’s wrong is mine, but I’m afraid that isn’t quite true!’ He and Ventris did have some friendly disagreements, and very occasionally these survive in printed form in the footnotes of Documents – but the vast majority of the interpretations were jointly agreed, even if more of the book was written by Ventris than by Chadwick.

For most of that summer of 1954 Ventris was in Greece, and he returned there again the following summer. In the one-year interval between his visits, Documents in Mycenaean Greek was swiftly written, incorporating the very latest tablets from Crete, Pylos and Mycenae, which Ventris translated almost as they came out of the ground, to the excitement of the Greek workmen in the trenches. The Mycenae tablets were especially interesting because they included a list of spices such as cumin, fennel, sesame, coriander and mint, and real seeds were also found (though unfortunately they did not live up to hopes that the botanists would match plants and Linear B names). Bennett and Wace offered all possible assistance, but there was some attempt at secrecy from Blegen, which crumbled in the face of Ventris’s charm and by now unavoidable fame.

Officially, during both those summers he had gone to Greece as an architect, i.e. a draughtsman-surveyor, for a new British excavation directed by a friend, Sinclair Hood, at the rather remote little harbour of Emborio near the southern tip of Chios, one of the Greek islands off the coast of Turkey. The site had been settled during Minoan times in the early Bronze Age, abandoned at the end of the Bronze Age, and then reoccupied by Greeks in early classical times despite the rugged mountain terrain around the harbour. It was Ventris’s task, helped by his wife some of the time, to map the structures from various periods that the excavators and he discovered. Although there were no tablet finds, here was a nearly ideal, not to say idyllic way to combine his two key interests: architecture and decipherment.

It is revealing to compare two verbal snapshots of Ventris at Emborio. Dilys Powell, the writer and Hellenophile, was there as a relatively casual visitor. She saw ‘a reserved young man with dark hair and serious refined features’, who with his wife formed an ‘industrious pair’ regularly to be seen ‘setting off with their notebooks in the long shadows of early morning or the stunning heat of afternoon towards the foundations of an archaic temple high in a hollow of the hills’, as she wrote in The Villa Ariadne in the 1970s.

John Boardman, one of the expedition’s archaeologists (later professor of classical archaeology at Oxford), remembered vividly almost fifty years later someone who was ‘quiet, witty, generous, not at all “imposing” despite his achievement with Linear B, nor at all scholarly in the usual way’. But it was Ventris’s ability to improvise that struck Boardman most. ‘Drawing walls in the excavation trenches he would rely, in the drawing of stones, more on what he knew to be the length of his own foot than on tedious measuring with a tape; he threatened to paint his wife in 50 cm stripes so that she could serve as a mobile sighting pole; he devised various impromptu aids for the excavator such as a simple way of determining circumference from sherds. There seemed a sort of instinctive method in everything that he did which went beyond the commonplace – he found a bracelet dropped by my wife in a grassy field which we had given up for lost – and he deduced areas to search and what to observe. He was intrepid too: while scuba-diving he speared an eel which we ate. It seemed not at all surprising that such a man could have both the patience and the vision to achieve the decipherment, since it required both, to a high degree. He seemed interested in everything and challenged to understand everything.… He was really not a humanities intellectual at all.’

A site map of Emporio (or Emborio), Chios, drawn by Ventris, 1954.

(Published in Excavations in Chios – see Further Reading for publication details)

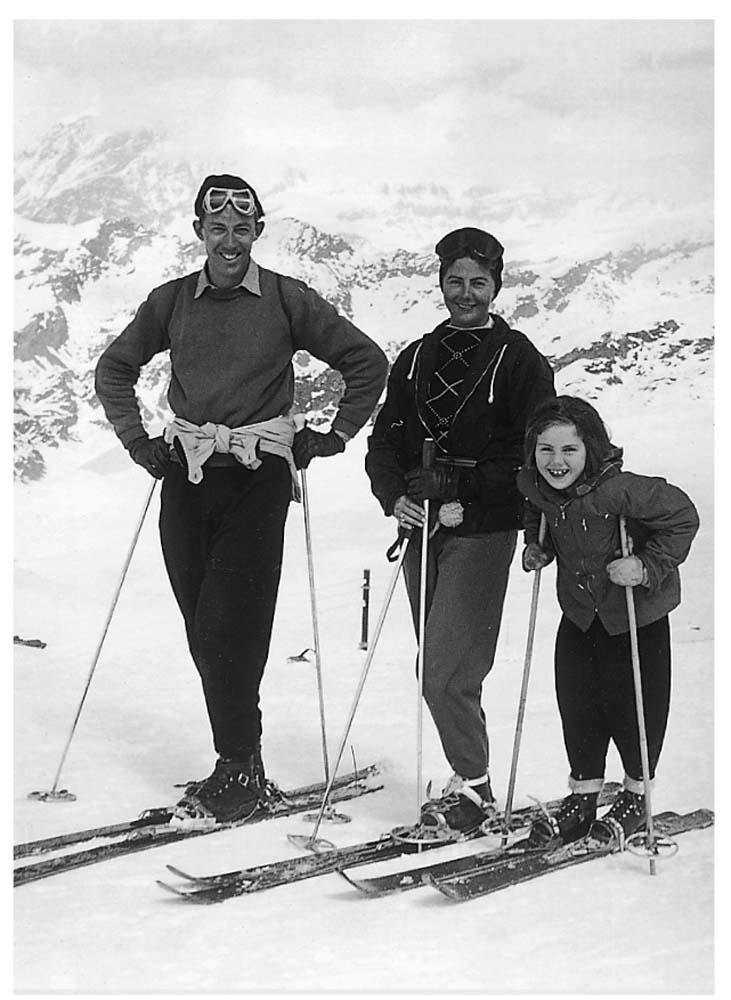

Michael, Lois and Tessa Ventris on holiday.

(Ventris papers)

In fact diving became quite a passion with Ventris. It took him a week of tracking the eel to its lair off the coast before he finally got it. (Sadly it tasted like fishy ‘cotton wool’, according to Sinclair Hood’s future wife Rachel.) A letter written to his wife in early August, after she left for home to look after the children, is decorated with a charming sketch of himself in goggles, snorkel and flippers, swimming backwards and playing ‘follow my leader’ with some small fish. And he wrote to Chadwick: ‘I have a daily encounter with a really large green fish in a hole under the rocks, but he’s outwitted me so far and is getting warier every day.’

Then he returned to the world of classical linguistic scholarship. In late August, no doubt sporting a superb tan, he addressed the 2nd International Classical Congress in Copenhagen, one of his favourite cities. When he showed his best exhibit, the slide of the ‘tripods’ tablet P641, the whole of the large audience burst into applause before he had said a word (as reported to Chadwick – but not by the reticent Ventris). However he cautioned the audience that although many key scholars now agreed that the Linear B language was Greek, ‘ten people can be just as wrong as one’. Chadwick, to his great disappointment, could not attend the conference because his fare was not paid and he did not feel able to accept Ventris’s offer to pay it himself.

Offers to join the academic world (although he had not even attended a university) were now his for the asking. But Ventris spurned them all. In November 1954, for instance, he was invited to give the Waynflete lectures at Oxford in 1955–56, following Lewis Namier, Max Born, Steven Runciman and other very distinguished figures. The hope was that he would bring the significance of the decipherment to a wider audience ‘in a way likely to cut across faculty boundaries’. He replied significantly: ‘Though it is unfashionable to confess it, I am chiefly interested in the more esoteric technicalities of the subject, in the details of writing systems and language structure. There are already ample signs of readiness among archaeologists, historians and Homeric scholars to explore the wider implications of the tenuous clues which Chadwick and I hope to have provided, and I feel they are better qualified to do this than I am.’ His priority, he said, must be to complete Documents in Mycenaean Greek. He also remarked that since he was ‘by profession an architect’, he did not want to commit himself to Mycenaean studies too far into the future.

The writing of the big book was now entering its most intense phase, with Ventris and Chadwick in constant and lengthy communication by letter, and very occasional meetings between them. Their discussion was almost exclusively technical, at a level requiring a deep knowledge of Greek, so it is impenetrable to all but specialists. Many details they debated remain unresolved to this day. However there are a few points that are more generally accessible and that illustrate the problems of decipherment mentioned earlier. We shall look at only two.

The phrase tiripo eme pode owowe in the ‘tripods’ tablet illustrated on page 119 was translated by Ventris and Chadwick as ‘tripod cauldron with a single handle on one foot’. But this does not match the pictogram accompanying the phrase,  , which definitely shows a tripod cauldron with two handles. The meanings in Greek of the three words, eme (‘one’ in the dative case), pode (‘foot’ in the dative case) and owowe (‘one-handled’), are not really in dispute, since they are supported by clear analogies in the rest of the ‘tripods’ tablet and in some other tablets. The difficulty is how to combine the words plausibly. Since, judging from the pictogram, the top of the tripod could not be one-handled, the single handle could only be on the foot of the tripod; Ventris and Chadwick showed a drawing of an excavated Mycenaean ‘incense burner’ in support of their contention:

, which definitely shows a tripod cauldron with two handles. The meanings in Greek of the three words, eme (‘one’ in the dative case), pode (‘foot’ in the dative case) and owowe (‘one-handled’), are not really in dispute, since they are supported by clear analogies in the rest of the ‘tripods’ tablet and in some other tablets. The difficulty is how to combine the words plausibly. Since, judging from the pictogram, the top of the tripod could not be one-handled, the single handle could only be on the foot of the tripod; Ventris and Chadwick showed a drawing of an excavated Mycenaean ‘incense burner’ in support of their contention:

However this interpretation was obviously open to criticism, so in the second edition of Documents published long after Ventris’s death, Chadwick offered a new one: that the tripod cauldron has only one handle and only one foot (the other two must have been broken off or burnt off) – in other words, owowe and eme pode are taken separately, no longer together. So why then does the pictogram show a cauldron with two handles and three feet? In response, Chadwick suggested that ‘the effort of depicting recognizably a tripod cauldron with two of its feet missing would be beyond the artistic powers of the scribe’, and that the sign is actually a ‘stereotype’, which does not show the missing feet (or the missing handle). Supporting this stereotype notion, the American classicist Tom Palaima (a student of Bennett) observed: ‘I was not troubled when I saw a bare-headed man in jeans and a T-shirt come out of a men’s room in a restaurant in south-west Turkey that was identified on its door by a pictogram of a tall thin man in a conservative Cary Grant suit wearing a stetson hat and smoking a pipe. The distinctive feature of a tripod is its three feet, even if two happen to be damaged or missing in a particular instance.’ Agreed, but still the explanation seems a little lame. On the very same tablet, the scribe plainly had no difficulty in representing goblets with four, three and no handles. There seems no compelling reason why a tripod cauldron should be depicted stereotypically, but a goblet should look realistic.

The second problem is in some ways easier to grasp. Another Pylos tablet, very carelessly written and therefore hard to read, nevertheless clearly contains the names of gods and goddesses and mentions the bringing of gold bowls and people to a shrine. For instance, one line reads: ‘To Posidaeia: one gold bowl, one woman’; another: ‘To Zeus: one gold bowl, one man’. The tablet’s introductory line contains the word po-re-na, which appears to define the nature of all this sacrificial activity, but its meaning here is not clear, though other words definitely say that some of the gifts were ‘carried’ to the shrine, while other gifts were ‘led’. The first edition of Documents contained a faint hint that human sacrifice was involved, but by the time of the second edition, human sacrifice was accepted, at least by Chadwick, as a likely explanation – despite the revulsion of many scholars – partly because archaeological evidence had been discovered suggesting that the Mycenaeans may have sacrificed human beings. (More evidence has appeared since 1973.) As he wrote in The Mycenaean World in 1976, ‘though the Greeks of the classical age disapproved of the practice, they were familiar with it from Homer, and it forms an essential element in the plot of many tragedies.’ Possibly the Pylos victims were hastily sacrificed to avert the fall of the city, just before its end, which might account for the scribbled poverty of the signs. But having said this, less lurid interpretations are possible; and the fact remains that there are many disputed meanings in this tablet.

The typing of Documents in Mycenaean Greek was done by Ventris, partly on a Varityper at University College London. It was a complex and demanding job, made harder by this technology – at least in comparison to an electronic word processor. ‘I wish I could pay God to finish it’, Ventris wearily joked to the Greek scholar Eric Handley who occupied the office next door. But by the time he left for Greece in the summer of 1955, the labour was done. In July, Chadwick handed over the complete manuscript to Cambridge University Press, and informed Ventris in Greece with a postcard written in Linear B.

By the time he returned to England, it appears that Ventris was beginning to lose interest in the new subject he had launched. His letters to Chadwick and Bennett tail off. He did continue to attend the meetings of the London seminar, and he did agree to take part in an inaugural International Colloquium of ‘Mycenologists’ (a new word in the scholarly lexicon) scheduled for April 1956, which was to be held near Paris at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), organized by two scholars from a country that had hitherto played remarkably little part in the decipherment. Yet one senses that Ventris’s heart was not in the meeting.

He complained to Chadwick about scholars such as Palmer ‘frittering our whole energy away in discussion’. ‘The whole Paris thing is rather a bore, but evidently we must prepare something for it. I have the feeling that 95% of our time gets used up on administration rather than creative work, but I suppose that’s the penalty for the start we have on the others.’ By early December, while Palmer was ‘showering…rather magisterial missives’ on the organizers of the London seminar, Ventris got back to the Varityper to produce an index of Mycenaean vocabulary for the French meeting. ‘It’s quite a job, as I am having to check through about six lists and books simultaneously’. Finally, in what appears to have been his very last letter to Chadwick, written just before Christmas, he informed his collaborator: ‘I seem to have lined myself up a year’s architectural research job beginning mid-January. This won’t affect Paris, which I shall attend; nor, I hope, will it cut down the speed I can get proof-reading of the book done. But it means I shan’t be able to devote time to any other major commitments. Once the two present pieces of typing are done, there’s not much for me to do anyway except argue with Palmer, and that comes better from you.’

Once again, as in 1948 when he abruptly cut off from Sir John Myres’s publication of Scripta Minoa, Ventris’s inner conflict had surfaced disruptively. In the final year of his life, it would become even more acute.