The plan was almost certainly Thistlewood’s and it went like this. All the king’s ministers were to be targeted and murdered in their town houses. The Duke of Wellington, as Master-General of the Ordnance, had his famous house at Hyde Park Corner with its grandiose address of 1 London. Lord Liverpool, the Prime Minister, of course resided at 10 Downing Street. Lord Castlereagh, the Foreign Secretary, lived in St James’s Square, not a stone’s throw from the haunt of prostitutes and gambling ‘hells’. Lord Harrowby, President of the Privy Council, had his house at 39 Grosvenor Square. And so on. In fact, the only prominent address not whispered about in the half-darkness of some radical tavern in the early weeks of 1820 was Carlton House, the private residence of the Prince Regent. Perhaps he was considered such a nonentity that he was not worth killing. Or perhaps, taking a leaf out of the French revolutionaries’ book, they intended to make the heir to the throne some sort of citizen-king.

The next decision to be made was – when? William Harrison, as an ex-Life Guards man, had been talking to one of his old comrades still in the service and gleaned some useful information. For such multiple assassinations to work, there would have to be minimal strike capability from the authorities – the police and the army. The death of George III provided the solution. On the evening of 29 January, the ‘old, mad, blind, despised and dying king’1 as Shelley called him, finally succumbed after years of mental and physical pain. On 31 January, the Prince Regent was proclaimed George IV and troops outside Carlton House cheered dutifully. It was a month of mixed emotions for George. On the one hand, he was king in name as well as deed after effectively ruling the country for nine years. On the other hand, his father had died only six days after his younger brother, the Duke of Kent. And the new king’s mind was already bent to his first royal problem – what to do about his ghastly, estranged wife, Caroline of Brunswick.

The old king’s funeral was scheduled for 15 February and Harrison’s old comrade had assured him, in the course of an innocent conversation, that every London soldier would be at Windsor. Thistlewood reasoned, perhaps bizarrely, that they would be too exhausted to get back to London to handle a revolutionary mob on the rampage.

The killing of the ministers was to be decided by lot. The conspirators would be divided into units, each one led by an assassin. During these discussions, duly debated and voted on, in true democratic fashion, James Brunt seemed to be keener on total, unswerving loyalty than anyone else. ‘Whatever man the lot fall upon’, a witness quoted him at his trial, ‘and fails, I swear by all that is good, that man shall be run through on the spot.’2

While all this slaughter was going on, John Palin’s task would be to disable various army barracks by throwing grenades into the straw. In the case of cavalry barracks, like that of the Life Guards in Knightsbridge, the stables were built below the men’s sleeping quarters so that the rising flames would be easily lit in the first place and would engulf the first storey. Men and horses would die, either from their burns or from choking on the acrid fumes. Whatever the outcome, the troopers would be too busy fighting fires and saving lives to worry about little things like insurrection.

Conspirator Cook’s job was to secure artillery. There were a number of mini-arsenals in London, apart from the Tower and Cook’s remit was to grab them before the authorities did. There were two field pieces at the Artillery Ground and more at the London Light Horse Volunteer barracks, both off Holborn. Thus armed, the revolutionaries and their by now growing cohorts would move east, placing their cannon in the Cornhill and next to the Royal Exchange and would call upon the residents of the Mansion House to surrender. This would become the headquarters of the new provisional government which would be set up under Thistlewood. The next target was the Bank of England and the decision was made to preserve the huge account books so that proof of the government’s financial mismanagement and plain embezzlement could be shown.

Other members of the team were to patrol the routes out of London and still others to disable the telegraph so that the capital was essentially sealed off. Communication during the night would be by the call sign ‘button’. One conspirator would whisper ‘b-u-t’ to another, who would reply ‘t-o-n’ and messages could be sent in this way from street to street.

Part of this plan was lifted directly from the mish-mash of Spa Fields. Part of it smacked of Despard. None of it made any real sense. Unlike Spa Fields, Thistlewood does not seem to have worked on soldiers’ loyalties, so the only reliance was on most troops being out of town for the king’s funeral. In the days before the event, a number of conspirators were buying up weapons – the odd carbine, blunderbuss and sword. The money seemed to come mostly from Edwards who, oddly, went from the poverty of a model-maker with little work, to a man well dressed, able to buy weapons and stand drinks. The equipment obtained, powder and ball shot as well as the makings of hand-grenades, was stored at Brunt’s house in Fox Court and Tidd’s in Hole-in-the-Wall. There had to be a base for operations and this is where Harrison came in. He acquired a hay-loft over a cowshed or stable in Cato Street, off the Edgware Road, and everything seemed ready.

It was now, almost at the last moment, that the plan changed. The king’s funeral idea was dropped, exactly why is unclear and on Tuesday morning, 22 February, Edwards brought news to the committee at Brunt’s that the Cabinet dinners, cancelled in respect of the king’s death, were to be resumed the following night at Lord Harrowby’s in Grosvenor Square. Thistlewood sent out for a paper and sure enough, there it was, listed in the New Times. Brunt was delighted

Now I will be damned if I do not believe there is a God. I have often prayed that those thieves [the Cabinet] may be collected all together, in order to give us a good opportunity to destroy them and now God has answered my prayer.

The new plan was now as follows. The conspirators had the time and place – Grosvenor Square shortly after 7. Everyone would be in the square by then, taking advantage of the buildings and trees as hiding places and Thistlewood would knock on Harrowby’s door with the pretext of an urgent note. The servants would be eliminated first, threatened with pistols. If they refused to obey or showed any signs of fight, hand-grenades were to be lobbed in amongst them while the leaders went for the Cabinet. Ings in particular saw it all very clearly:

I will enter the room first, I will go in with a brace of pistols, a cutlass and a knife in my pocket and after the two swordsmen [the ex-cavalrymen Harrison and Adams] have despatched them, I will cut every head off that is in the room and Lord Castlereagh’s head and Lord Sidmouth’s I will bring away in a bag . . . As soon as I get into the room I shall say ‘Well, my Lords, I have as good men here as the Manchester Yeomanry. Enter citizens and do your duty.’3

By Wednesday morning, Thistlewood was drawing up last-minute paperwork. Again in Brunt’s house in Fox Court, he was drafting a manifesto when Adams arrived. He had written:

Your tyrants are destroyed. The friends of liberty are called upon to come forward. The provisional government is now sitting.

It had that day’s date, 23 February, and was signed by James Ings, Secretary. And that, as far as anyone knows, is as far as plans for the revolution ever got.

‘Cato Street is rather an obscure street,’ wrote George Wilkinson in his preface to the trial transcripts, ‘and inhabited by persons in an humble class of life.’ It runs parallel with Newnham Street, joining John and Queen Street. It was virtually a cul-de-sac in 1820, open at one end for carriages and almost closed at the other by posts. The conspirators’ headquarters was a dilapidated stable near the open end, belonging to a General Watson, who was away in Europe. Drawings made at the time show a two-storey, flat-roofed building with a set of double doors (for carriages) and a side door on the ground floor with one window covered with a shutter. There were two windows and a door on the first floor, the door presumably to allow hay to be lifted in and out from a wagon in the street below.

A single set of stairs led up to the loft which was divided into three rooms, one large, two small. Only one of the smaller rooms had a fireplace and on the night in question, as well as conspirators and their weaponry in residence for what Thistlewood called ‘the West End job’, there was a hammock, a carpenter’s bench, a chaff cutter, a tool chest, a tub and a corn measure.

On the afternoon of 23 February, various people were seen coming and going into the stable, each time locking the door behind them. Sacking was nailed across the upstairs windows to minimize nosiness, but the conspirators had reckoned without the curiosity of their neighbours. George Kaylock at 22 Cato Street saw Harrison and somebody else going in about 5 o’clock. Kaylock spoke to him, to be told that Harrison had taken two rooms in the building and was going to ‘do them up’. Between 5 and 7 at least twenty ‘decorators’ were seen arriving. Richard Monday, living next door at number 23 saw Davidson standing under an archway at 20 past four. He knew the man, having seen him in company with Firth the cow-keeper, from whom Harrison had hired the premises. Monday had just come home from work. He had his tea and went to the pub (almost certainly the Horse and Groom across the road). On his return, he saw Davidson carrying a bundle into the stable and noticed he now had a pair of pistols and a sword at his belt. Elizabeth Westall, from number 1 (next door to the stable), had already seen a man carrying a sack entering the premises at about 3 o’clock. She was somewhat unnerved when Davidson knocked on her door to ask for a light. We cannot know now whether the woman was alarmed by Davidson’s colour (which she mentions) or his brazen cheek. Nor can we know why Davidson seemed determined to draw attention to himself. The light was to light the candles in the hay-loft, but surely the conspirators could have brought their own.

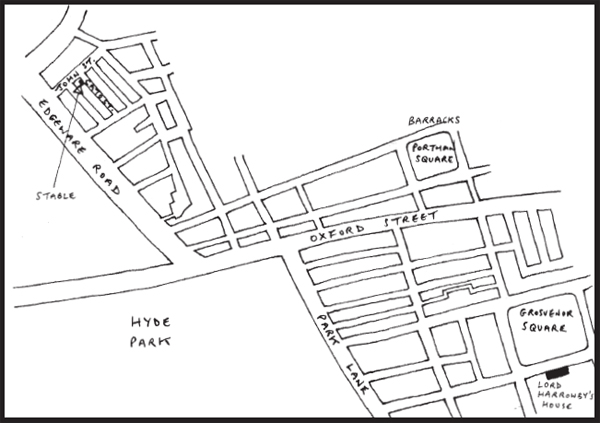

Tha Cato Street Night – a simplified map showing the stable in relation to Lord Harrowby’s house, fifteen minutes walk away.

Such was the level of secrecy – or perhaps the lack of planning – that not all the conspirators knew the stable rendezvous. Some were told to meet at the Horse and Groom, others to go to John Street and from there, they were taken to the hay-loft. Thistlewood, Ings and Wilson were already there and everybody was told to help themselves to the pistols, swords, grenades and home-made pikes littering the place.

Tidd was late, but Thistlewood calmed everybody down by pointing out that various key people were elsewhere and that not everybody was going to Grosvenor Square. About 7 o’clock the Lincolnshire man turned up with a relative newcomer, John Monument, and by this time there were twenty-five men crammed into that small loft, making their final preparations.

On the ground, Ings and Davidson were on sentry duty, the butcher armed with his knife. He had tied twine around the hilt so that the weapon would not slip as he went about his gruesome business at Harrowby’s.

Across London, in Grosvenor Square, whoever was detailed to keep watch there noticed nothing amiss. Servants and deliverymen came and went as if in preparation for a dinner. A dinner that was never to happen. A dinner that only existed as part of an elaborate trap. It would have taken the Cato Street conspirators between ten and fifteen minutes to reach Grosvenor Square – ‘at that hour when suspicion must be lulled asleep and when no apprehensions could be entertained of personal danger’ – but other feet were on the move before theirs. They belonged to George Ruthven and eleven men of the Bow Street patrol.

This forerunner of the Metropolitan Police was set up in the house of a former magistrate, Sir Thomas de Veil, in 1739 but was effectively created in its best known form by the Fielding brothers, Henry and John, both magistrates, in 1751. The six original Runners had no uniform and no pay, but they were allowed the reward given to thief-takers and this was incentive enough. There were always two officers on duty, day and night, and, rather like the detective branch of Scotland Yard which replaced them, had a brief to investigate crime anywhere in the country. By the 1770s their reputation had grown enormously. These were not the lame and ancient ‘Charlies’, parish constables who patrolled the streets and called the hour, but fit, active men who could be relied upon to stop criminals in their tracks. They were now paid 1 guinea a week out of a Secret Service Fund. Any whiff of a paid police force would have outraged liberal society and riff-raff alike; there was something so European about it. From the abortive attempt on the life of George III in 1786 (when a woman had tried to stab him with a blunt fruit knife) two officers were permanently assigned to protect him. Doubtless they were in the royal box in May 1800 when James Hadfield tried to shoot the king.

Seven other police offices were opened in London in 1792, each one with six Runners attached. It was the very plain-clothes-ness of the Runners that made them so useful. Although they occasionally wore scarlet waistcoats, which earned them the nickname of ‘Robins’, Cruikshank’s sketch of the arrest of the Cato Street men shows the officers in long top coats, double-breasted jackets, tan-topped hunting boots and breeches. The only things that mark them out of the ordinary are their pistols and cutlasses. Interestingly, Cruikshank’s depiction of the moment of the murder of ‘Smithers the Police Officer’ sees him dropping his brass tipstaff. These were issued to every Runner and magistrate in London – some of them are still preserved at the London Museum and the Police College in Bramshill. It goes without saying, of course, that Cruikshank cannot resist propaganda. The police officers are clean-cut, well dressed (and, by definition, outnumbered) whereas the conspirators, even a gentleman like Thistlewood, are shown as scruffy, uncouth ruffians with desperate eyes.4 Some of the less committed are already climbing up through the roof to make good their escape.

Because Ruthven’s Runners could blend so well, the conspirators seemed unaware that their movements were being watched the whole day. Once Richard Birnie, the Bow Street magistrate, was sure that the Cato Street hay-loft was the focus of activity, he swore out a warrant for the arrest of Thistlewood, Brunt, Hall, Ings, Potter, Palin, Edwards, Shaw, Adams, Tidd, Wilson, Davidson, Harrison and Cook. There is some confusion over whether Ruthven actually took the paper with these names on it to the stable. His brief was to arrest anyone there and he was told to expect support from the Coldstream Guards from the Portman Street Barracks nearby.

It was probably half past 8 by the time Ruthven reached Cato Street and already something had gone wrong. There were no soldiers in place that Ruthven could see and from the conspirators’ point of view, they themselves should have moved off at least forty-five minutes earlier. The first person Ruthven saw, armed with a sword and with a blunderbuss resting on his shoulder, was William Davidson. He saw someone else too, almost certainly Ings, but couldn’t make him out in the shadows. He yelled at his men to grab these two and made for the stairs.

This was little better than a ladder and would only permit one person through the open trapdoor at a time. Putting his head over the rim, in the candle-light he saw twenty-four or twenty-five people squeezed into a room 15 feet long. He clambered up, followed by his colleagues Ellis and Smithers. The only man he recognized was Thistlewood, standing to the right of the carpenter’s bench.

‘We are officers,’ Ruthven shouted. ‘Seize their arms.’

Thistlewood retreated slightly into the doorway of one of the rooms behind him. He had a long, drawn sword in his hand (probably cavalry pattern although great play was made at his trial that this was of foreign manufacture) and, as Smithers crossed to him, Thistlewood lunged, driving the blade through the Runner’s body. The man fell back, blood trickling over his waistcoat and fell against Ellis, gasping, ‘Oh, my God! I’m done!’

Someone yelled, ‘Put out the lights – kill the buggers and throw them down the stairs.’ Thistlewood slashed several of the candles with his sword and in pitch blackness, all hell broke loose, everybody making for the stairs. With great presence of mind, Ruthven joined in the cry to ‘kill them’ and bolted down the steps in the guise of a conspirator.

The murder of Smithers happened in seconds and, in the confusion, men had different memories of it. James Ellis who had been right behind Ruthven on the stairs was sure there were three men at ground level. Davidson, ‘a man of colour’, wore cross belts and was carrying a carbine, not a blunderbuss.5 On the stairs, Ellis heard the scraping of feet and ‘a noise like fencing with swords’. Had Smithers drawn his cutlass and did he attempt to outfence Thistlewood? Once on a level with the others, Ellis brandished his tipstaff. This was not only a symbol of office, but with its metal crown head, quite a nasty weapon. He called on Thistlewood to surrender or he would fire and pointed his pistol at him. As Thistlewood stabbed Smithers and the officer fell, Ellis fired, but missed. He did not record, at the trial, how he got to the ground floor, but presumably joined in the headlong rush to freedom with the others.

Other than the dead man, then, only Ruthven and Ellis were witness to the murder itself, but that was enough and at ground level, there was chaos. At last the soldiers had arrived, a detachment of the Coldstream Guards under Captain6 Fitzclarence, an illegitimate son of the Duke of Clarence. Although he did not mention it at the trials, he had been incorrectly briefed and not only thought that the piquet was to fight fires but he had gone to the wrong end of John Street, 70 yards away. The sound of gunfire had brought him and his men to the right spot.

Here, Fitzclarence met Ruthven and by this time the conspirators were shooting their way out. It was of course pitch black in that cul-de-sac and most of the streets around would have been in darkness. Apart from the Coldstreamers, whose buttons and musket locks would presumably have reflected any available light, it was not easy to tell Runner from conspirator. Runner William Westcott had stayed on the ground the whole time and heard firing in the loft. Ings made a bolt for it and Westcott tussled with him. He obviously broke free because, the next thing Westcott remembered, Thistlewood was hurtling down the stairs firing at him. Instinctively, the Runner dropped to the ground, later to find three bullet holes in his hat7 and a wound to the back of his hand where a ball had grazed him. Thistlewood hacked at Westcott with his sword before vanishing into the West End night.

Ruthven saw a man who turned out to be Richard Tidd making a dash for the door.

I met Tidd grappling with one of the military. I secured him. I caught hold of his right arm, pulled him round and fell with him on a dung heap.8

He was taken, along with others, across the road to the Horse and Groom. Ellis heard a cry in the midst of the shooting and saw Davidson running along Queen Street, still armed with his sword and carbine. He grabbed him and helped with the arrest of four others during the night. William Brookes was not from the Bow Street patrol, but was pressed into service by Magistrate Birnie who was by now at the scene himself, directing operations in the middle of the fight. Immediately Brookes came face to face with Ings and someone else armed with a cutlass. Ings fired and wounded Brookes in the shoulder before running off in the direction of the Edgware Road. Although in pain and shock, Brookes gave chase and was probably relieved to see Ings throw away his pistol. In the event another policeman, Giles Moy, collared Ings and a disbelieving Brookes asked why he had fired at him. ‘I wish I had killed you,’ Ings grunted.

While Fitzclarence was confronting a swordsman at the bottom of the stairs – ‘Don’t kill me,’ the conspirator blurted, ‘and I will tell you all’ – his men were doing stalwart service all around him. As another conspirator tried to escape, he was grabbed by a guardsman who slipped and the conspirator

presented a pistol at [Fitzclarence’s] breast; but as he was in the act of pulling the trigger, Sergeant Legge rushed forward and, whilst attempting to put aside the destructive weapon, received the fire upon his arm.

The ball scraped along his sleeve from wrist to elbow, but did minimal damage.

Davidson in particular put up a fight. He slashed at Fitzclarence with his cutlass but missed, and Private James Basey hauled him down, suffering only a cut finger. ‘Fight on while you have a drop of blood in you,’ Davidson shouted to the others still milling at the stable entrance, ‘You may as well die now as at another time.’

Fitzclarence seems to have been the first up into the loft. There was gunsmoke all around him and the first thing the officer saw was the bloody body of Smithers and one of the conspirators kneeling beside him. Whoever it was was also soaked in blood, which turned out to be the dead man’s. ‘I hope they will make a difference,’ he pleaded, hands in the air, ‘between the innocent and the guilty.’ Three men cowering in a corner were hauled out, one jabbering, ‘I resign myself. There is no harm. I was brought here innocent this afternoon.’

With these four and three more the Runners had captured below, there were now seven men in effective custody. Perhaps the luckiest in the whole incident was Private Muddock of the Guards. Stumbling in the darkness of the hay-loft, he tripped over a conspirator who fired at him at point blank range. Fortunately, the gun misfired and the conspirator threw it away, shouting, ‘Use me honourably’. The pistol was loaded nearly to the muzzle.

No one was asked or commented on how long the hand-to-hand fighting in Cato Street went on, but it cannot have been more than ten or fifteen minutes. While the police herded the prisoners into the Horse and Groom, the soldiery were employed collecting the weaponry from the loft – ‘a great quantity of pistols, blunderbusses, swords and pikes, about sixteen inches long, made to screw into a handle’. There were also ball cartridges, powder flasks and a sack full of hand-grenades. The conspirator prisoners and their weapons were marched off to Bow Street, while the body of Smithers was taken down from the loft and laid out in a back room of the Horse and Groom. Magistrate Birnie interviewed four of Fitzclarence’s men – John Revel, James Basey, William Curtis and John Muddock – before allowing them, with their captain (whose uniform was in shreds) to return to their barracks. For safekeeping, the ammunition and weapons went with them and were locked in Fitzclarence’s quarters.

Now Birnie went to work on the Bench. Before him were: James Ings, Richard Bradburn, James Gilchrist, Charles Cooper, Richard Tidd, John Monument, John Shaw and William Davidson. Some of these men were already known dissidents. Inevitably, Davidson stood out. He sang ‘Scots wha ha’e wi’ Wallace bled’9 while Runner Ellis clapped the cuffs on him and snarled, ‘Blast and damn the eyes of all those who would not die for liberty.’ Ellis recognized the man at once as one of the principal speakers at Finsbury Market a few months earlier and a black-flag carrying rabble-rouser in Covent Garden.

Wilkinson wrote:

Ings was a fearful ruffian, a rather stout man, apparently between 30 and 40, but of a most determined aspect. His hands were covered with blood and as he stood at the bar, manacled to one of his wretched confederates, his large fiery eyes glared round upon the spectators with an expression truly horrible.

If only half the description of the appearance and behaviour of Ings is acceptable, the man was the most deranged of the lot.

Each man in turn was asked if he had anything to say. Only Cooper and Davidson spoke, reminding the authorities present that they had instantly surrendered (which in the case of Davidson, was patently untrue).

At 9 o’clock on the morning of 24 February, Ruthven, Lavender, Bishop, Salmon and six other Runners were sent to pick up Thistlewood. There was of course a warrant out for the others, like John Palin and George Edwards. Most of these conspirators were never seen again. Wisely, Thistlewood had not gone straight home to Stanhope Street, but had holed up at 8 White Street, Little Moorfields.

The Runners divided their number, half at the front, half at the back, and Daniel Bishop got the key from the landlady, a Mrs Harris. He opened the door as quietly as he could and let his eyes become accustomed to the darkness. A head popped up from the covers and Bishop’s pistol was already aimed at it. ‘Mr Thistlewood, I am a Bow Street officer. You are my prisoner,’ and he launched himself at the conspirator, pinning him to the bed. With the other Runners holding him, Thistlewood was handcuffed. He was still fully clothed and had ball cartridges and flints in his pockets.

By this time, news of Cato Street had spread throughout London and a mob had gathered at Bow Street, jostling Thistlewood as he was taken in to see Birnie. ‘Hang the villain! Hang the assassin!’ was the general cry. While waiting in an anteroom, Thistlewood admitted he knew he had killed one man and hoped it was Stafford, the chief magistrate. Birnie interviewed Thistlewood briefly and then the conspirator was sent to the Home Office, under close guard to be interrogated by the very men he had planned to kill.

Large numbers of eminent people came to gawp at him and his reaction was hardly surprising. ‘His appearance’, wrote Wilkinson, ‘was most forbidding. His countenance, at all times unfavourable, seemed now to have acquired an additional degree of malignity.’ He calmly drank some porter (beer) and asked the names of those who had come to see him. He asked what gaol he was to be sent to and hoped it was not Horsham.

At 2 o’clock, Thistlewood was placed, still handcuffed, before the Privy Council. Wellington was there, along with Harrowby, Liverpool, Westmoreland, Sidmouth, Eldon, Vansittart, Canning, Castlereagh, Wellesley Pole, Scott, Sir S Shepherd (ex-Attorney-General), Bragge Bathurst and others. It must have been a surreal moment. Thistlewood, shabby and emaciated in comparison with his appearance at the Spa Fields trial, looking one by one at the men who, but for fortune, would now be dead. The heads of Castlereagh and Sidmouth were not on poles on London Bridge, but still on the shoulders of their owners. The Lord Chancellor told him that he would be charged with murder and treason. Asked if he had anything to say, Thistlewood declined at that stage. He was committed to Coldbath Fields in the custody of six officers, while the Privy Council looked in horror at the weapons of their own destruction which were now placed before them.

Large numbers of people flocked to the stable at Cato Street when an enterprising local, with no authority, started to demand a shilling entry. This was all part and parcel of the obsession with violence that would dog the rest of the century. When William Corder killed Maria Marten seven years later, virtually the whole of the Red Barn where her body was hidden was dismantled and taken away by souvenir hunters.

Earlier that day, Sidmouth had issued a statement to the Press. The London Gazette wrote:

Whereas Arthur Thistlewood stands charged with high treason and also with the wilful murder of Richard Smithers, a reward of One Thousand Pounds is hereby offered to any person or persons who shall discover and apprehend . . . the said Arthur Thistlewood . . . upon his being apprehended and lodged in any of His Majesty’s gaols. And all persons are hereby cautioned upon their allegiance not to receive or harbour the said Arthur Thistlewood, as any person offending herein will be thereby guilty of high treason.

‘Gentlemen,’ said Mr Bolland, junior counsel for the prosecution at the trial of Thistlewood. ‘Thank Heaven that Providence which kindly watches over the acts and thoughts of men, mercifully interposed between the conception of this abominable plot and its completion.’

But Providence and Heaven had nothing to do with it. The Privy Council were up all night on 23 February and none of them – not even Lord Harrowby – was at Grosvenor Square. Even though Thistlewood was under arrest by the time the Gazette appeared, he was not when Sidmouth sent them his note. And when exactly did Sidmouth find out that it was Thistlewood who had killed Smithers? And whatever happened to that word ‘alleged’ which is enshrined in English law? In other words, Thistlewood’s neck was in the noose before any legal decision had been made and twelve police officers and a piquet of the 2nd Coldstream Guards were despatched to a run-down cowshed in an obscure street . . . on the off-chance of preventing a revolution? And how was the Bow Street magistrate Richard Birnie able to swear out a warrant for precisely those men found in the hayloft?

The real conspirators in the Cato Street story were their lordships of the Privy Council.