In the popular mind, the history of Hong Kong, long the point of entry to China for Westerners, begins in 1841 with the British occupation of the territory. However, it would be wrong to dismiss the long history of the region itself. Archaeologists today are working to uncover Hong Kong’s past, which stretches back thousands of years. You can get a glimpse into that past at Lei Cheng Uk Han Museum’s 1,600-year-old burial vault on the mainland just north of Kowloon (for more information, click here). In 1992, when construction of the airport on Chek Lap Kok began, a 2,000-year-old village, Pak Mong, was discovered, complete with artefacts that indicated a sophisticated rural society. An even older Stone Age site was discovered on Lamma Island in 1996.

Time travel

The Hong Kong Story at the Hong Kong Museum of History is the best way for a visitor to experience the territory’s past. You can enter the museum free of charge and travel from a point 400 million years ago to the 1997 handover. Exhibits are richly displayed and include replicas of an 18th-century fishing junk and a 1960s cinema.

While Hong Kong remained a relative backwater in its early days, nearby Guangzhou (Canton) was developing into a great trading city with connections in India and the Middle East. By AD900, the Hong Kong islands had become a lair for pirates preying on the shipping in the Pearl River Delta and causing a major headache for burgeoning Guangzhou; small bands of pirates were still operating into the early years of the 20th century.

In the meantime, the mainland area was being settled by incomers, the ‘Five Great Clans’: Tang, Hau, Pang, Liu and Man. First to arrive was the Tang clan, which established a number of walled villages in the New Territories that still exist today. You can visit Kat Hing Wai and Lo Wai, where the old village walls are still intact. Adjacent to Lo Wai is the Tang Chung Ling Ancestral Hall, built in the 16th century, which is still the centre of clan activities to this day.

The first Europeans to arrive in the Pearl River Delta were the Portuguese, who settled in Macau in 1557 and had a monopoly on trade between Asia, Europe and South America for several centuries. As Macau developed into the greatest port in the East, it also became a base for Jesuit missionaries; it was later a haven for persecuted Japanese Christians. While Christianity was not a great success in China, it made local headway, as can be seen today in the numerous Catholic churches in Macau’s historic centre.

The British arrive

The British established their presence in the area after Emperor Kangxi of the Qing Dynasty opened trade on a limited basis in Guangzhou (Canton) at the end of the 17th century. Trading began smoothly enough, but soon became subject to increasing restrictions, and all foreigners were faced with the attitude expressed by Emperor Qianlong at Britain’s first attempt to open direct trade with China in 1793: ‘We possess all things,’ said the emperor, ‘I set no value on objects strange or ingenious, and have no use for your country’s manufactures.’

Moreover, China would accept nothing but silver bullion in exchange for its goods, so Britain had to look for a more abundant commodity to square its accounts. Around the end of the 18th century the traders found a solution: opium was the wonder drug that would solve the problem. Grown in India, it was delivered to Canton, and while China outlawed the trade in 1799, local Cantonese officials were always willing to look the other way for ‘squeeze money’ (a term still used in Hong Kong).

In 1839, the emperor appointed the incorruptible Commissioner Lin Tse-hsu to stamp out the smuggling of ‘foreign mud’. Lin’s crackdown was severe. He demanded that the British merchants in Canton surrender their opium stores, and to back up his ultimatum he laid siege to the traders, who, after six tense weeks, surrendered over 20,000 chests of opium. To Queen Victoria, Lin addressed a famous letter, pointing out the harm the ‘poisonous drug’ did to China, and asking for an end to the opium trade; his arguments are unanswerable but the lofty, though heartfelt, tone of the letter shows how unprepared the Chinese were to negotiate with the West in realistic terms.

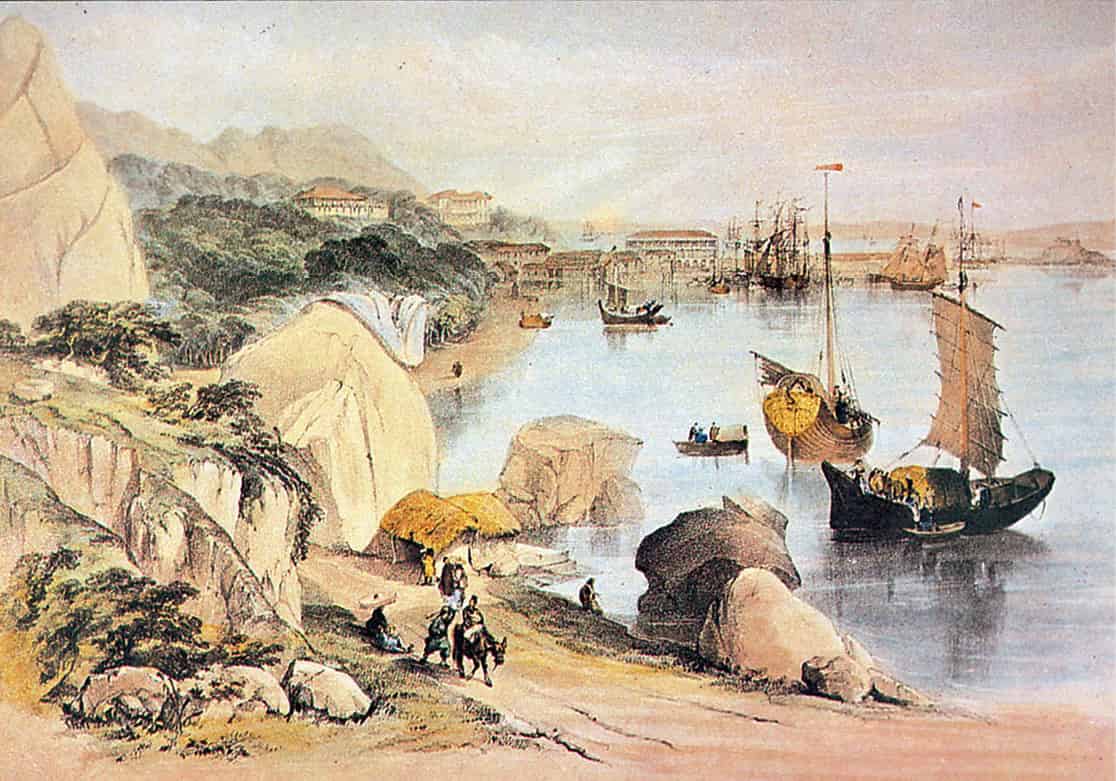

Emperor Kangxi opened trade in Guangzhou on a limited basis

Public domain

The Opium Wars

A year later, in June 1840, came the British retaliation, beginning the first of the so-called Opium Wars. After a few skirmishes and much negotiation, a peace agreement was reached. Under the Convention of Chuenpi, Britain was given the island of Hong Kong (where it had been anchoring its ships for decades), and on 26 January 1841, Hong Kong was proclaimed a British colony.

The peace plan achieved at Chuenpi was short-lived. Both Peking and London repudiated the agreement and fighting resumed. This time the British forces, less than 3,000 strong but in possession of superior weapons and tactics, outfought the Chinese. Shanghai fell and Nangking was threatened. In the Treaty of Nanking (1842) China was compelled to open five of its ports to foreign economic and political penetration, and even to compensate the opium smugglers for their losses. Hong Kong’s status as a British colony and a free port was confirmed.

In the aftermath of the Opium Wars, trade in ‘foreign mud’ was resumed at a level even higher than before, although it ceased in 1907. Opium-smoking continued openly in Hong Kong until 1946; it was abolished by the Communist government in mainland China in 1949.

An amusing isle

‘Albert is so amused,’ wrote Queen Victoria, ‘at my having got the island of Hong Kong.’ Her foreign secretary, Lord Palmerston, was not so amused; he dismissed Hong Kong as ‘a barren island with hardly a house upon it’.

19th century commerce and prosperity

The first governor of Hong Kong, Sir Henry Pottinger, predicted it would become ‘a vast emporium of commerce and wealth’. Under his direction, Hong Kong began its march towards prosperity. It was soon flourishing; with its natural harbour that attracted ships, Hong Kong leaped to the forefront as a base for trade. Both the population and the economy began to grow steadily. A surprise was the sizable number of Chinese who chose to move to the colony.

Causeway Bay in the mid-1800s

Public domain

In the meantime, the opening of Hong Kong was the last blow to Macau’s prosperity. Inroads had already been made by the arrival of the Dutch, and Macau’s loss to them of the profitable Japanese trade. From then on, up until its 21st-century comeback as Asia’s gambling capital, Macau sank into relative obscurity.

Despite the differences between the Chinese majority and the European minority, relations were generally cordial. Sir John Francis Davis, an early governor, disgusted with the squabbling of the English residents, declared: ‘It is a much easier task to govern the 20,000 Chinese inhabitants of the colony than the few hundreds of English.’

There were a few incidents: On 15 January 1857, somebody added an extra ingredient to the dough at the colony’s main bakery – arsenic. While the Chinese continued to enjoy their daily rice, the British, eating their daily bread, were dropping like flies. At the height of the panic, thousands of Chinese were deported from Hong Kong. No one ever discovered the identity or the motive of the culprits.

Conditions in the colony in the 19th century, however, did not favour the Chinese population. The British lived along the waterfront in Victoria (now Central) and on the cooler slopes of Victoria Peak. The Chinese were barred from these areas, and from any European neighbourhood. They settled in what is now known as the Western District. It was not uncommon for several families and their animals to share one room in crowded shanty towns. So it is not surprising that when bubonic plague struck in 1894, it took nearly 30 years to fully eradicate it. Today in parts of the Western District, you can still wander narrow streets lined with small traditional shops selling ginseng, medicinal herbs, incense, tea and funeral objects.

In 1860, a treaty gave Britain a permanent beach-head on the Chinese mainland – the Kowloon peninsula, directly across Victoria harbour. In 1898, under the Convention of Peking, China leased the New Territories and 235 more islands to Britain for what then seemed an eternity – 99 years.

Trading Houses

The Hong Kong of today owes its origins to the big trading houses or hongs of the 19th century. It was their top bosses or taipans who pressured the British government to secure a base to freely trade their opium and, once acquired, they were the driving force behind shaping the ‘barren rock’ into a successful trading port. Even today, places in Hong Kong bear the names of these big taipans as testament to their early power.

Rival hongs such as the Scottish Jardine, Matheson and England’s Dent and Company were constantly squabbling among themselves. They were also at loggerheads with the government, which was chasing taxes and urging better treatment of the local Chinese. To avoid paying taxes many taipans became honorary consuls of foreign powers or sailed their ships under foreign flags.

Many of these hongs still exist today, successful because they diversified as Hong Kong’s economy changed. Their offices are now hidden in the morass of skyscrapers, their interests spread widely through subsidiaries and some bought out by Chinese taipans. Although they no longer rule the roost, they still wield power from behind the scenes.

20th century intrusions

The colony’s population has always fluctuated according to events beyond its borders. In 1911, when the Chinese revolution overthrew the Manchus, refugees flocked to the safety of Hong Kong. Many arrived with nothing but the shirts on their backs, but they brought their philosophy of working hard and seizing opportunity. Hundreds of thousands more arrived in the 1930s when Japan invaded China. By the eve of World War II, the population was more than one and a half million.

Old and new buildings contrast in Hong Kong

Alex Havret/Apa Publications

A few hours after Japan’s attack on the American fleet at Pearl Harbor in December 1941, a dozen Japanese battalions began an assault on Hong Kong; Hong Kong’s minimal air force was destroyed on the airfield at Kai Tak within five minutes. Abandoning the New Territories and Kowloon, the defenders retreated to Hong Kong island, hoping for relief which never came. They finally surrendered on Christmas Day in 1941. Survivors recall three and a half years of hunger and hardship under the occupation forces, who deported many Hong Kong Chinese to the mainland.

A number of Hong Kong’s monuments were damaged: St John’s Cathedral became a military club, the old governor’s lodge on the Peak was burned down, and the commandant of the occupation forces rebuilt the colonial governor’s mansion in Japanese style. At the end of World War II, Hong Kong’s population was down to half a million; there was no industry, no fishing fleet and few houses and public services remaining.

Post-war Hong Kong

China’s civil war sent distressing echoes to Hong Kong. While the Chinese Communist armies drove towards the south, the flow of refugees into Hong Kong gathered force, and by the time the People’s Republic of China was proclaimed in 1949, the total population of Hong Kong had grown to more than two million people. The fall of Shanghai in 1949 brought another flood of refugees, among them many wealthy people and skilled artisans, including the Shanghai industrialists who became the founders of Hong Kong’s textile industry. Housing was now in desperately short supply. The problem became an outright disaster on Christmas Day in 1953. An uncontrollable fire devoured a whole city of squatters’ shacks in Kowloon; 50,000 refugees were deprived of shelter.

The calamity spurred the government to launch an emergency programme of public-housing construction; spartan new blocks of flats put cheap and fireproof roofs over hundreds of thousands of heads. But this new housing was grimly overcrowded, and even a frenzy of construction couldn’t keep pace with the increasing demand for living space. In 1962, the colonial authorities closed the border with China, but even this did not altogether stem the flow of refugees: the next arrivals were the Vietnamese boat people.

Hong Kong’s economy boomed in the 1970s and 1980s, thanks largely to its role as China’s trading partner, and as a result the standard of living in the colony rapidly improved.

Back to China

As 1997 drew near, it became clear that the Chinese government would not renew the 99-year lease on the New Territories. Negotiations began and in 1984, then British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher signed the Sino-British Joint Declaration. Britain confirmed the transfer of the New Territories and all Hong Kong to China in 1997. China declared Hong Kong a ‘Special Administrative Region’ and guaranteed its civil and social system for at least 50 years.

Housing for the masses

Ming Tang-Evans/Apa Publications

Although China’s Basic Law promised that Hong Kong’s existing laws and civil liberties would be upheld, many in Hong Kong were concerned. The British Nationality Act (1981) in effect prevented Hong Kong citizens from acquiring British citizenship, and thousands of people, anxious about their future, were prompted to apply for citizenship elsewhere, notably Canada and Australia. Some companies moved their headquarters out of Hong Kong.

Ironically, as the handover approached, the British granted the Hong Kong Chinese more political autonomy than they had since the colony was founded, including such democratic reforms as elections to the Legislative Council.

Hong Kong in the 21st century

The transfer of sovereignty occurred smoothly on 1 July 1997, but the Asian economic downturn hit Hong Kong hard in the years that followed. Then, in 2003, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) killed 299 people in the city, but its people showed great resilience. In July 2003 more than half a million protestors marched peacefully to protest against proposed anti-subversion laws. The following year 200,000 marched and established the tradition of annual ‘July 1st marches’, calling for more democracy and voting reforms. In 2013, Benny Tai Yiu-ting, Associate Professor of Law at the University of Hong Kong, launched a civil disobedience campaign and started the Occupy Central with Love and Peace movement to pressure Beijing and the SAR administration to introduce universal suffrage. Protests (Umbrella Revolution) continued in September–December 2014, resulting in the SAR promising to submit a “New Occupancy report” to the Chinese Central Government. In January 2015 a proposal for electoral reform was announced, which in the end was not implemented. In 2017, Beijing-supported Carrie Lam was appointed as the Chief Executive by the Election Committee and not by the public vote.

Despite these political issues, Hong Kong today remains undeniably optimistic. Analysts say that ‘three flows from China’ are now driving Hong Kong’s economy – goods, visitors and capital. In 2010, the move back to Hong Kong from London of HSBC’s CEO was seen as highly symbolic of the shift in the world’s economic centre of gravity to China.