In ancient times and during the Middle Ages, Basques were famous for their skills in the practice of fortune telling; today it can be stated, at the risk of sounding prejudiced, that no one in France is more superstitious than the Basques, except maybe the Bretons.

—Francisque Michel, LE PAYS BASQUE, 1857

AS A SYMBOL OF their new order, the Jesuits chose not a cross but a sun with its rays stretching toward a circular border. The symbol is ubiquitous in Basqueland, although in modern times the number of curved spokes filling the circle has been reduced to four, giving the appearance of a cross—a concession Ignatius de Loyola did not find necessary. This “Basque cross,” as it is frequently called, predates Christianity and is not a cross at all.

The Basque cross appears to be related to sun worship. The original Basque religion was directly associated with nature— sun gods, moon gods, rock gods, tree gods, mountain gods. Such spirits were often animal-like but sometimes took human form and often were a combination. Residents of different valleys worshiped different spirits. In many valleys, the sun, eguzki, was the eye of God, jainkoaren begi.

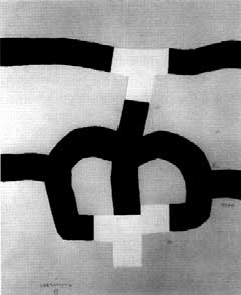

Grave markers that pay homage to the sun have been found in Basqueland dating from the first century B.C. well into medieval times. These rough, thick stones tell the story of Basque conversion, displaying every conceivable variation on the sun from concentric circles to starlike bursts. In time, they more and more resembled crosses, and some stones even have a sun on one side and a cross on the other. Traditional rural Basque houses are still built with the doorway facing east, the direction of the rising sun. This is especially true in Labourd, where the winds and rains are westerly, making the east the sheltered part of the house. Even in contemporary abstract art, the two leading Basque sculptors, Eduardo Chillida and Jorge de Oteiza, both use the circle as a central motif. Oteiza, who first came to international prominence in 1958 by winning a sculpture prize in São Paulo for a steel ring with a strip curving through it, explains, “In the circle we have a tie to the sacred form, the solar circle and especially full moons, and such a primitive religious frame-of-mind, which is realized in these little circles, serves to regenerate our moral conscience.”

The image in the lower right-hand corner is a fresco of the Jesuit seal, circa 1600, from Ignatius Loyola’s room in Rome. The remaining five images are ancient Basque gravestones, the dates of which range from 100 B.C. to A.D. 200 (top row) to after A.D. 833 (lower left-hand corner). The center images are opposite sides of the same stone. (Stones used by permission of Euskal Arkeologia, Etnografia eta Kondaira Museoa, Bilbao)

But for centuries before contemporary abstract Basque art, these circular sun images, Basque crosses, were carved over the doorways of homes. Carvings of roosters were sometimes added to further greet the rising sun. “Sun, sacred and blessed, rejoin your mother” are the ancient words still repeated in modern times as a bedtime prayer.

Once the Basques turned to Christianity, they became, and have remained, the most devout Catholics in Europe. But because Basques keep their traditions, these devout Catholics have many strange practices, symbols, and beliefs. Basques have had a persistent belief in the existence of jentillak, gentiles, non-Christians who wander the woods and remote rural areas with terrifying pre-Christian magical powers. Some rural Basques still believe that an ax stored in the house with the blade up protects the house from lightning. Bread blessed on Saint Agatha Day is believed to protect against fire, and bread from Saint Blaise Day guards against floods. If this bread or blessed salt is fed to animals, these creatures will protect the house.

IN THE EARLY YEARS of Christianity, hermitism was a common phenomenon, not only in the Basque region but throughout northern Iberia. Devout men lived harsh, ascetic existences alone in mountain huts. In the year 800, one such hermit in the northwestern Galicia region of Iberia saw a shaft of brilliant light. Following this beam, he came upon a Roman cemetery. Under the shaft of light he found a small mausoleum concealed by overgrown vines, weeds, and shrubs. Since beams of celestial light don’t lead to just anyone’s grave, he concluded that this must have been the burial place of Saint James, Santiago, brother of John the Divine. The cemetery became known as Campus Stellae, the star field, and later Compostela.

Silkscreen with relief by Eduardo Chillida for Amnesty International. Note the use of a circle with a line through it, a reference to the ancient Basque symbol.

According to legend, James, one of the first disciples chosen by Jesus, after the crucifixion went off to a distant land, sometimes specified as Iberia, to find converts. Having failed, he returned to Jerusalem, where he was beheaded by Herod, who refused to allow his burial. Christians gathered up his remains at night, placing them in a marble sepulchre, which they sent to sea aboard an unmanned boat. According to early Christian legend, the ship was guided by an angel to the kingdom of the Asturians, which is an area between Basqueland and Galicia.

The Church confirmed the hermit’s finding in Galicia and had a church built over the spot. As the legend grew, an outbreak of miracles and visions was reported from Compostela. Sometimes Saint James was portrayed as a pilgrim and sometimes as a Moor-slaying knight. It was the age of Moor slaying, and many of the miracles and legends had to do with the triumph of Christianity over Islam. Much evidence even suggests that the French had fabricated the legends about Santiago, or his body, going off to Galicia, because they wanted to rally Christendom to defend northern Spain. One legend from the time claimed that Charlemagne himself, the great anti-Moorish warrior who died in 814, had found the body of Santiago in Galicia.

Just as it had become a fashion to demonstrate faith by making the journey to Jerusalem, thereby asserting that it was a Christian and not a Muslim place, it became a fashion to make a pilgrimage to Christian-held Galicia in Moorish Iberia and to pray at the tomb of Saint James. After the Muslims seized the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem in the late eleventh century and pilgrims stopped going to the Middle East, Santiago de Compostela became the leading Christian pilgrimage.

Pilgrims came from throughout Europe, especially from France. Some did not go by choice but were ordered as penance for some blasphemy or crime. Affluent criminals would hire impoverished people to make the pilgrimage on their behalf.

All of the European routes to Santiago passed through Basqueland. Some pilgrims crossed into Aragón and then traveled across Navarra, resting at the eighth-century monastery of Leyre, which means “eagerness to overcome” in Euskera. Today, seventh-century Gregorian chants are sung there seven times a day, before God alone or the occasional visitors, by exquisite voices selected from among the resident Benedictines. Other pilgrims took the coastal route from Labourd, crossing the mouth of the Bidasoa at Hendaye, to the cathedral town of Fuenterrabia across the bay and continuing along the coastlines of Guipúzcoa and Vizcaya. Still others crossed into Basse Navarre, resting at St.-Jean-Pied-de-Port before climbing through the narrow pass to Roncesvalles.

Because scallops are abundant in Santiago, the scallop shell became their symbol, which is why scallops are known in French as coquilles Saint Jacques, Saint James shells. Even today, pilgrims are seen in St-Jean-Pied-de-Port with scallop shells on their backpacks, buying supplies before continuing into the mountains.

Basse Navarre is very different from the pretty farmland of neighboring Labourd. It has a wild look with reddish ferns on the slopes and, on the crests, rough rock outcroppings like huge, gray jagged teeth. The last refuge, where pilgrims arrived to prepare for the crossing, was the walled town of St.-Jean-Pied-de-Port. In early morning light the pilgrims would leave the red stone gate traveling toward the steep green pastures that looked soft as chenille against the Pyrenees. The mountains in the morning seemed to form a colossal wall with gauzelike fog draped over the peaks. But there is a path through the wall from the little village of Arnéguy, up to Valcarlos where Charlemagne had waited for Roland, down again past little waterfalls and streams and up again to the heights of Ibañeta and then down once more to the pines of Roncesvalles, where in 1127 a resting home for pilgrims was built, a home which still stands today.

Centuries of passing pilgrims brought Romanesque architecture to Basqueland with its huge scale and carvings and ornaments, depicting biblical lessons to instruct travelers. The pilgrimage also spread French ideas. Many French pilgrims settled in the region, and monasteries in the Spanish Basque provinces came to have more in common with those of France than those of the rest of Iberia. When the monastery of Leyre decided to build a new church, the design was taken from Limousin. Perhaps the ultimate expression of the growing French influence was in the thirteenth century, when the royal house of Navarra, devoid of heirs, turned to French families to continue the monarchy.

Arnéguy in the early twentieth century. The small stone bridge is the border between France and Spain.

Yet in spite of this seemingly considerable openness to the French, Aimeric de Picaud warned pilgrims that they would be poorly received by the Basques. This twelfth-century French monk—the same man who concluded that Basques were of Scottish descent because they wore skirts—wrote a five-volume work, probably with the backing of the influential Cluny monastery in Burgundy, collecting all the stories, legends, and miracles connected with Saint James and including practical information for traveling pilgrims. This work, the Liber Sancti Jacobi, which is still kept at the cathedral of Compostela, became widely known in medieval Europe as the Codex of Calixtus. The latter title comes from a story circulated by Aimeric de Picaud, which is today dismissed as a complete fabrication, that Pope Calixtus II sent the text for editorial comment to the patriarch of Jerusalem and the archbishop of Santiago. Approval of the text, according to Aimeric de Picaud, arrived in the form of a vision.

Included in this divine text is a section on “the crimes of the bad innkeepers along the way of my apostle.” According to Aimeric, the Basques, and especially the Navarrese, were crude, spoke primitively, and were given to crime. The Codex describes them as “enemies of our French people. A Basque or Navarrese would do in a French man for a copper coin.” He recounted how pilgrims would find themselves surrounded by Basques demanding payment. If they refused, they would be stripped and robbed and sometimes, he claimed, killed.

Aimeric made numerous references to wanton sexuality. “When the Navarrese get excited, the man shows the woman and the woman shows the man, that which they should keep concealed. The Navarrese fornicate shamelessly with animals. They say that a Navarrese keeps his mule and his mare chained up to keep others from enjoying them.”

Aimeric de Picaud came from the Poitiers region and lived during the time of the Crusades, the Chanson de Roland, and considerable anti-Muslim frenzy. As pilgrims climbed through the pass to the heights of Ibañeta, now the famous site of Roland’s death, and down to the hospice at Roncesvalles, taking time to contemplate in the pine woods where the Basque ambushers once hid, an understandable confusion about Basques and Muslims may have translated into anti-Basque sentiment.

In any event, no other record of the nature of Basque relationships with mules is to be found, and while a few stories of occasional unscrupulous innkeepers have been written, clearly the Codex exaggerated. Aimeric de Picaud himself may have had some bad experiences while traveling. Whatever the reason, no people have ever paid so dearly for negative coverage in a travel book. The Codex was widely circulated, and in 1179 the French Church called for the excommunication of “Basques and Navarrese, who practice such cruelties to Christians, laying waste like infidels, sparing neither elderly, orphans, widows, or children.” In that epoch, a comparison to infidels was the harshest condemnation.

The Basques ever since have been chained to an enduring image as brutal, unfriendly, mercenary, and untrustworthy. The habit of distinguishing between “Christians” and Basques also endured.

WHEN A PEOPLE of strange practices and bad reputation collides with an age of intolerance, disaster seems inevitable. The time of the Protestant Reformation, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, was such a period.

The Inquisition had been created in medieval Aragón to guard the purity of the Church. Less than twenty years before the final defeat of the Muslims, it was reorganized and brought to Castile. After the victory of the Reconquista, Isabella extended its authority to the Spanish Empire from Sicily through Latin America. Other countries also had inquisitions, papal courts of inquiry. But the Spanish Inquisition was different because it was not controlled by Rome. The inquisitor general was appointed by the king of Spain, confirmed by the pope, and left to act however he saw fit. He had his own secret police, his own ministry, La Suprema, and his own prisons, ominously known as las cárceles secretas, secret prison cells.

All Inquisition officials and employees were sworn to secrecy, and all witnesses and accused were ordered to remain silent. The archives were closed. Not even the king could make inquiries about Inquisition proceedings except for financial matters, since the crown was owed a share of confiscated property. The accused, held incommunicado, vanished from sight for years with no explanation. Agents of the Inquisition were unpaid, but the coveted positions offered prestige, power, and privilege, including complete immunity from secular authority.

The Inquisition began hunting for hidden Jews following a 1391 order to convert to Christianity. In 1492, Jews were given four months to leave lands that had been family homes for almost a millennium in some cases. “We order them by the end of July to leave all the kingdoms and fiefdoms and never return,” said the decree. After the mass expulsion, the primary preoccupation of the Inquisition was uncovering clandestine Jews and Muslims. The Muslims, hidden Moors, were called Convertis, Moriscos, or Moriscotes. The hidden Jews were called Tornidoros or Marranos—pigs.

Some 300,000 people were expelled from Castile and Aragón. If they lived in western Castile, they fled to Portugal; from the south they went to Morocco; and from Aragón to Basque country. Basques on both sides of the border, being by then exemplary Catholics, cooperated, often with enthusiasm, in the hunt for Moriscos and Marranos.

Unlike Spain, France allowed Jews, though their activities and living areas were severely restricted. But Convertis and Marranos, hidden Muslims and Jews from Spain, were illegal. Nevertheless, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, a considerable population of Marranos from Portugal settled in French Basqueland, and the persistent accusation was that they engaged in contraband with Spain. In the late sixteenth century, French authorities were expressing great alarm over this discovery, even though smuggling had long been the stock-in-trade of the Basques without ever alarming anyone.

A Portuguese named Farcian Vaez was arrested in Labourd for Judaism, and it was reported that two bags of counterfeit money were found on him. According to his confession, probably forced, not only was he Jewish, but “all the Portuguese who pass through St-Jean-de-Luz practice Judaism and buy merchandise to sell in Spain.” He said the merchandise was purchased with counterfeit money made in Flanders.

In St.-Jean-de-Luz, the local clergy even suspected other priests, such as the Portuguese Father Antonio Leguel. Leguel was the only priest from whom his Portuguese community would receive the sacraments. He seemed an odd priest in that he never worked on Saturdays, and he was later exposed as a clandestine Jew. Local clergy knew to look for people who did not work on Saturdays or who made unleavened bread. Many Marranos made unleavened bread all year to avoid arousing suspicion at Passover time.

The Tribunal of Logroño, the regional tribunal of the Inquisition responsible for Spanish Basqueland, expressed the same frustration as have most institutions that have tried to control Spanish Basqueland: They could not control the French side. The Inquisition harbored a particular suspicion of Basques because they straddled the border. In 1567, an inquisitor reported from San Sebastián that the Basques were too close to the French and even spoke their language. In 1609, Léon de Araníbar, the abbot of Urdax, near the Dancharia pass that leads from the mountains of Navarra across the border to the woods of St. Pée, complained that mule caravans from Bayonne and St.-Jean-de-Luz could pass right under monastery walls and travel as far as Pamplona without anyone stopping them to search for heretical books.

The tribunal agreed that there was a problem with the area that was “under the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Bayonne.” The tribunal explained, “The majority of the priests are French; and we cannot entrust the affairs of the Holy Office to them.”

The Inquisition decided to plant its own spy in the St.-Jean-de-Luz Jewish community. Ironically, the French frequently and illogically complained that Marranos in their midst were spying for Spain. Now the Inquisition hired Marcos de Llumbre, a St.-Jean-de-Luz resident from San Sebastián, to pose as a Marrano and spy for Spain. But posing as a Jew posing as a Christian proved difficult, and the Jews of St.-Jean-de-Luz quickly saw through de Llumbre’s attempts to infiltrate their community.

In 1602, yielding to popular pressure, the French king Henri IV ordered all Portuguese Jews out of Labourd in a month. A process of expulsion, town by town, began with Bayonne but was never effective since the Jews would just move to the next town. But Jews from Bayonne and St.-Jean-de-Luz began immigrating to Baltic cities with more open and accepting societies. Others resettled in other parts of France, including St Esprit, a neighborhood of Bayonne designated as a Jewish ghetto because, being on the opposite bank of the Adour, it was out of Basqueland and in the region of Landes.

THE COUNTER-REFORMATION, so staunchly backed by the Jesuits, had ushered in the great age of persecution. The Council of Trent met in the Italian Alps between 1545 and 1563 and, recognizing that the Protestants were not going to come back to the Church without military force, defined the Catholic position. The council was supposed to usher in a reform of the Church, but only the most orthodox elements won the debates. Once the Church had redefined itself and irrevocably drawn the lines between Catholic and Protestant, the Christian world was found to be in an epidemic of heresy.

Now there were not only the Jews and the Muslims to flush out, but the Protestants, who in turn were having their own heresy hunts in the north. And there were the Bohemians (Gypsies) and Cagots.

Cagots were descendants of the Visigoths. The original Cagots may have been lepers, or perhaps just had a psoriasis-like skin disease. Outcasts in France, they were driven to the southwest, into Basqueland, and Cagot ghettos emerged in St.-Jean-Pied-de-Port, by the nearby deep green valley of the Aldudes, and in the port of Ciboure, which was on the wrong side of the river in St.-Jean-de-Luz. Water touched by Cagots was considered contaminated, and they were barred from all trades involving food, including agriculture. They became noted for their carpentry.

Until the early seventeenth century, despite their pariah status, Cagots were considered good Christians and were protected by the Church. But in 1609, Judge Pierre De Lancre, French Basqueland’s most rabid witch hunter, said at his infamous St.-Jean-de-Luz witch trial that Cagots and Bohemians, both residing across the river in Ciboure, were consorting with the devil.

“Wandering Bohemians are part-devils,” De Lancre said of Gypsies. “I say these nationless long-hairs are not Egyptian, nor from the Kingdom of Bohemia, and are born everywhere while passing through countries, in the fields and under a tree, and dance and juggle like at a witches’ sabbath.”

No one who could be identified as distinct and different was safe in this age. It is inevitable that in such an era, the Church would also grow concerned about Basque heresy. In past times of intolerance, Basques had been lumped with other undesirable groups. In fourteenth-century Huesca, an area east of Navarra, an ordinance forbade the speaking of “Alavan, Basque, or Hebrew” in the market place. The Basques had accepted the persecution of Jews, Muslims, Lutherans, Gypsies, and Cagots. They should have been able to see that they would be next.

BY THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY, witchcraft should have seemed a ridiculously old-fashioned accusation. In 787, Charlemagne had outlawed the execution of witches and made it a capital crime to burn a witch. A tenth-century Church law, Canon Episcopi, demanded that priests preach against belief in witchcraft as superstition. By the fourteenth century, stories of witchcraft were widely dismissed among educated circles as a primitive belief of peasants.

But by the late sixteenth century, the Canon Episcopi, which had been universal Church law, was being circumvented by the claim that society was faced with a new and more virulent form of witchcraft and therefore the old laws did not apply. Witches, poor rural women, were consorting with the devil just like the Protestants, Jews, Muslims, Gypsies, Lutherans, and Cagots.

Neither De Lancre’s trials in St.-Jean-de-Luz nor the Tribunal of Logroño betray even a hint of cynicism. All evidence indicates that even some of the most fantastic tales told by witnesses and in confessions were believed at face value.

The Canon Episcopi had cautioned that women who claimed to be flying through the air on the backs of wild animals were in reality remaining on the ground and simply having hallucinations induced by the devil. Yet somehow, seven centuries later, men of the Church, of law, of learning, appeared to believe that women in the mountains of northern Navarra were rubbing an ointment on their bodies in order to fly through the sky to witches’ sabbaths.

Doubts lingered. Interrogators earnestly tried to make a distinction between true events and the sort of delusions referred to in the Canon. Among the questions prepared by the tribunal was whether rubbing ointment and then flying was the only way to get to the sabbath.

In spite of the improbability of many of the accusations, it is striking how widely accepted they were. Even in modern times, this history is often treated as incidents of witchcraft, rather than incidents of mass hysteria. It seems likely that a frightened peasantry, attacked for being different, was coerced into absurd confessions. But rather than asking why this persecution took place, the question frequently asked is why the practice of witchcraft occurred. Pío Baroja, son of a distinguished journalist and himself a doctor and prominent twentieth-century novelist, rather than try to explain seventeenth-century witch hunting, attempted to explain why there were so many witches. He suggested that perhaps pre-Christian Basque beliefs had combined with a movement rebelling against the Church.

Baroja’s nephew, Julio Caro Baroja, a leading ethnologist, set off a witch craze in Basqueland in the 1970s with the publication of scholarly studies. Despite Caro Baroja’s reasoned books exploring the nature of the hysteria, it became fashionable once again to talk about Basque witchcraft not as a persecution by the authorities but as an exotic folk practice.

Pío Baroja had reversed the old bigotries, and rather than blame the Arabs and Jews, argued proudly that witchcraft was a uniquely Christian phenomenon. “In Semitic religions,” he wrote, “the woman is always seen banished from the altars, always passive and inferior to men.” In primitive European religions, on the other hand, according to Pío Baroja, “the great and victorious woman appears. Those first Christians—the Jewish race—did not have, could not have a cult of the Virgin Mary.”

But if belief in witchcraft was about empowering women, as Pío Baroja asserted, the witch hunts themselves were clearly an attack on women. Although a few men were also accused of witchcraft, the essential belief was that a woman with power necessarily used it for evil. De Lancre made this clear in the 1600s in his embrace of an old Semitic myth about women. In explaining why the Basques were afflicted with so many witches, he said, “This is apple country: the women eat nothing but apples, they drink nothing but apple juice, and that is what leads them to so often offer a bite of the forbidden apple.” And it is true, though not necessarily suspicious, that the people in Labourd, Guipúzcoa, and Navarra eat a great deal of apples and drink a lot of cider in the winter.

The antiwoman aspect of witch hunting becomes clearer when examining the nature of some of the allegations. The emphasis was on sexual perversion. Pío Baroja even offered lust as one of the possible motivations for practicing witchcraft. Women flew to secret rendezvous, where orgies were conducted with the devil. These clandestine orgies were known in Euskera as akelarre. The word comes from akerr, meaning a “male goat,” and larre, meaning “meadow.” The witches allegedly flew to a secret meadow and had group sex with a billy goat.

The accusation is reminiscent of Aimeric de Picaud’s concern for mares and mules. What stronger denunciation of an agrarian society than the charge of bestiality? Even in modern times, when Basque peasants engage in the duel by insults known as xikito, the accusation of bestiality remains a classic attack. And though to most people, sex with a goat would seem sufficiently perverted, it was not even conceded that they had conventional goat sex. It was group sex, and the goat sometimes used an artificial phallus, with the intercourse sometimes vaginal and sometimes anal. According to some accounts, the goat would lift his tail so the women could kiss his posterior while he broke wind.

The goat was a typical convergence of Basque and Christian imagery. It is horned and therefore associated with the devil. Martin Luther was sometimes depicted as a goat. But a black billy goat was also an important spirit in the pantheon of pre-Christian Basques. In the modern-day carnival of Ituren, which, like witchcraft, is a complex blend of pagan and Christian, a goat appears. Carnival, the last fling before lent, celebrates permitting the impermissible. While the joaldunak, grim-faced men in sheepskin with high cone-shaped hats who ring copper bells strapped to their backs, come and go from the mountains, clanging their huge bells, people appear dressed as monsters spraying hoses or as farmers throwing mud. The most frightening character of all, the one that always scatters the children, is a man dressed head to toe as a huge billy goat.

THOSE ACCUSED OF WITCHCRAFT, being held in secret cells, their whereabouts unknown to the world, torture chambers awaiting, were urged to confess. Confession was rewarded with leniency. Many who confessed to the Inquisition were simply condemned to a few years’ banishment from their native village. A convicted heretic was an outcast for life, forbidden to ride a horse, barred from owning weapons, silk, pearls, or precious metals. If a heretic was burned, the stigma was passed to her family.

The accused was not initially informed of the charges. She was simply told to confess what was in her heart. If the accused waited until being charged, it was too late to avoid torture. The Inquisition, contrary to popular belief, saw torture as a last resort and was suspicious of confessions coerced by violence, though all confessions were made at least under the threat of violence.

Accusations of witchcraft were usually initiated by Basque peasants settling a grudge or explaining a misfortune. In Pío Baroja’s novella La Dama de Urtubi, a young man runs off to America to earn wealth and stature so he can court an aristocratic woman. But when he returns, he finds that she is interested in another man and concludes that the two have been bonded by a witch’s spell.

This is typical. A crop fails, someone falls ill, the apple tree didn’t bear fruit. Someone had clearly cast a spell. And there was often agreement on who the witch was—a woman who seemed to hold a grudge for some perceived wrong.

At the edge of St Pée, a forest begins which crosses the border at Dancharia, near Urdax, and drops down into a deep valley where villages are built in the dark quiet mountain crevices and farmers work the rugged airy slopes. In 1608, a young woman named María de Ximildegui returned to her native village of Zugarramurdi in this self-contained little world. The village, whose name means “hill of elms,” would never be the same.

An illustration of the Basque billy goat by Jean Paul Tillac (1880-1969) for a book by Arthur Campión. Born in the French southwest, Tillac, whose drawings chronicled Basque life, had one Basque grandparent. (Collection of the Musée Basque, Bayonne)

Young María de Ximildegui had spent several years across the border in Ciboure. Her family had remained there, but she returned to her hometown, where she informed the local authorities that she had been a witch in Labourd, and during that time she had attended a sabbath in Zugarramurdi. She wanted to name names.

She said that while living in Ciboure, she had been an active witch for eighteen months before trying to break away, a struggle with the devil that resulted in weeks of illness. A priest in Hendaye had saved her through confession.

Ximildegui named twenty-two-year-old María de Jureteguía as one of the participants at the Zugarramurdi ceremony. Jureteguía, along with her husband, accused Ximildegui of lying. But in a public confrontation, Ximildegui was so convincing, offering meticulous details, that the townspeople began little by little to believe her and urged María de Jureteguía to confess. Too late, Jureteguía realized that she was now in the position of being a suspected witch. Overtaken with fear and the exasperation of what had turned into a losing shouting match, she fainted.

Later, the panic-stricken Jureteguía realized that since she was believed to be a witch, she could only save herself by the mercy that comes after confession. So she confessed to having been led astray by her fifty-two-year-old aunt, María Chipía Barrenechea. So began a string of denunciations that unraveled the village.

After her confession, Jureteguía said that she was being pursued by witches, whom she would try to fend off with the sign of the cross. She would see them in the yard disguised as cats, dogs, and pigs. The townspeople reacted to this news without a hint of skepticism and began searching houses for toads. They all knew that toads were necessary companions to witches. The toad search lead to Barrenechea’s octogenarian sister Graciana, who would in time confess to being the queen witch of Zugarramurdi.

The first four witches in Zugarramurdi were accused of using an assortment of spells and powders to kill a total of eighteen children and eleven adults, and cause various harm to people, livestock, and crops. Eventually, ten witches confessed to a several-decade crime spree that included killing children and sucking their blood.

Incredibly, in a tribute to local Basque law, the village was able to resolve the entire affair bloodlessly, and the confessed witches were pardoned. The matter would have ended had not someone, the source remains anonymous, gone to the Inquisition.

In 1609, four accused witches and an Euskera translator were taken from the village by the Inquisition. More and more villagers were arrested, and the confessions were spectacular. Jureteguía admitted to a childhood of witchcraft. She had guarded a flock of toads and was punished if she did not treat them with the utmost respect. Her aunt would sometimes reduce her to a minuscule size, enabling her to pass through tiny chinks in walls. Many admitted to passing through small holes. They described elaborate initiations in which they were presented with a well-dressed toad. They had sexual intercourse in a variety of ways with the devil and with each other, both heterosexually and homosexually, including with members of their own family, all supervised by the elderly Graciana Barrenechea. They also confessed to infanticide and vampirism, cannibalism, defiling of tombs, eating of corpses. One admitted poisoning her own grandchild.

They confessed to breaking every taboo of their society. Were they furiously inventing stories based on the gravest cultural prohibitions they could imagine? The confession rate was not high. In the 1610 trial, only nine out of twenty-one witches had confessed. By then, another thirteen had died in prison and six had already been burned. Those who did not confess were certain to be burned alive. The Inquisition handed out sentences at an elaborate public ritual known as an Auto de fe, an Act of Faith. Although the 1610 Auto de fe of Logroño is famous for its witches, eleven of whom were sentenced to burning, an additional twenty-five heretics were also sentenced, including six people found guilty of Judaism, one of Islam, one of Lutheranism, twelve of heretical utterances, and two of impersonating agents of the Inquisition.

Auto de fe only unleashed more accusations throughout northern Navarra and Guipúzcoa. Rural Basqueland seemed in the throes of a spreading witchcraft epidemic. In some towns, panicking villagers lynched women. By March 1611, the Inquisition had discovered that in little Zugarramurdi, the hill of elms, 158 people out of a total population of 390 were witches and another 124 were under suspicion. One-fifth of the population of the twin villages of Ituren and Zubieta were found to be witches. In all, 1,590 witches were discovered in Navarra, with another 1,300 under suspicion. In Guipúzcoa, 340 witches were found.

AT THE SAME TIME, Pierre De Lancre, the witch hunter of French Basqueland, suspected that the entire population of Labourd might be witches. A reign of terror, based in St.-Jean-de-Luz, began when an official in St. Pée complained to Henri IV of an increase in witches in the area. De Lancre, a fifty-six-year-old lawyer from Bordeaux, was asked to investigate. He said that he found “so many demons and evil spirits and so many witches within Labourd, that this little corner of France is the nursery.”

De Lancre had many theories on why the Basques were so afflicted. Part of their problem stemmed from Ignatius de Loyola and the traveling Jesuit missionaries. All that evangelizing in places like Japan and China had infected them with demons which they had carried back to Labourd.

Another source of difficulty unearthed by De Lancre was the side effects of tobacco. The Basques were the first Europeans to cultivate tobacco, and it seemed that this was rendering them a bit strange. “I feel, and it is certain, that it makes their breath and their bodies so foul smelling that the uninitiated cannot bear it and yet they use it three or four times a day,” De Lancre pointed out. This use of tobacco, he supposed, was affecting their reason.

He also expressed disdain for Basque women and said they produced undersized and cursed children who died. This last accusation may have had some truth, due to the Rh blood factor.

Who was this Basque hater from Bordeaux who wanted to execute Basques by the hundreds? Before his father had earned a title, the family name had been Rostéguy, a Basque name, probably originally Errotegui, meaning “the place with the mill.” His family had migrated to Bordeaux a century earlier and become aristocratic Frenchmen. De Lancre despised what he regarded as the backward superstitions of the Basques, their myths and folk remedies. But he seemed to truly believe in a physically manifest devil, who, he even claimed, visited his apartment one night.

Anyone found engaged in folk healing, divination, or other traditional practices, especially if it was a woman, was a candidate for burning. Like the Tribunal of Logroño, De Lancre believed that the devil marked the body of initiates. All he had to do was find the mark. A blood spot on the eye was the mark of the devil. But most marks were not this visible. Hundreds of men, women, and children were rounded up. The accused could confess and be spared the painful and humiliating inspection before being burned alive. Those who did not confess were completely shaved. The body was then pricked inch by inch until a spot was found that yielded no blood. To make sure, such a spot would be stuck deeper, but if no blood came forth, the mark had been found. Then, they too would be burned alive.

THE OFFICIALS OF the Spanish Inquisition came to understand that they were creating hysteria, that the more witches they burned, the more witches would be denounced. So they became more secretive and eventually even banned the burning of witches. The inquisitors went about their business, flushing out Lutherans, Jews, and Muslims, and even found a witch or two around Spain into the nineteenth century.

On the French side, as often happens with witch hunts, De Lancre’s terror seemed unstoppable until someone had the courage to denounce it, and then it quickly disintegrated. Jesuits and tobacco merchants weren’t the only Basques traveling the world. There were also the fleets that hunted whale and fished cod in Newfoundland.

When the St-Jean-de-Luz cod fleet, one of the largest, heard rumors of their wives, mothers, and daughters stripped, stabbed, and many already executed, the 1609 cod campaign was ended two months early. The fishermen returned, clubs in hand, and liberated a convoy of witches being taken to the burning place.

This one popular resistance was all it took to stop the trials. Some French historians have estimated that 600 accused witches had been burned. A Spanish commission studying the De Lancre trials reported only 80 burned, which may be conservative, but the exact number will probably never be known.

De Lancre retreated to Bayonne, where he began condemning Basque priests. He was soon recalled by the French crown to Bordeaux, where he died of natural causes, his reputation intact, at the age of sixty-eight, in 1631. In 1672, a royal edict banned witch trials in France. But even into the twentieth century some rural Basques continued to believe that a blood spot on the eye is the mark of the devil and that prayer books left open in church will let witches into the community.