Food is always, more or less, in demand.

—Adam Smith, THE WEALTH OF NATIONS, 1776

FOR THE REST of the world, the little-remembered Carlist Wars were to have only two lasting consequences: the invention of the political term liberal and the popularizing of the beret. These two brutal and complicated nineteenth-century civil wars were to shape the destiny of at least six generations of both Basques and Spaniards. Their enduring impact is most easily seen in features of daily life such as food and clothing. Carlism resulted not only in the famous Basque hat but in the creation of their most mysterious, and therefore some might argue, most Basque sauce.

According to popular and unverified legend, in 1836 a Bilbao salt cod merchant named Gurtubay placed an order by telegram saying, “Send me by the first ship that lands in Bilbao, 100 or 120 top quality salt cods,” which in Spanish was written “100 o 120 bacaladas.” The telegraph code was misinterpreted as “1,000,120 bacaladas.”

In any event, Gurtubay got a lot more salt cod than he had expected, and had no possibility of returning it, because by then the First Carlist War had begun and Bilbao was under siege. The mistake might have been ruinous had not the city started running out of supplies. As the food shortage became more severe, Bilbaínos became an eager market for Gurtubay’s million dried fish, and Gurtubay became a rich man, which is the way Basques like their stories to end.

It is often said that this is why the people of Bilbao eat so much salt cod, which is probably not true. The Basques, including Bilbaínos, had been eating salt cod since they developed the product many centuries earlier. But a typical salt cod dish of the day was a stew with many ingredients. During the siege, no fresh food could get in to the city, which in time left its inhabitants with little more than three nonperishable staples: olive oil, garlic, and dried pepper.

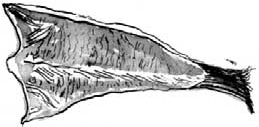

The First Carlist War, drawn by M. Miranda, Panarama Español, Madrid, 1842.

Salt cod cooked in olive oil with slices of dried guindilla pepper and garlic became a popular dish called pil pil, though the origin of this name is not clear. The tendency is to assume that this odd-looking term means something in Euskera. Disappointingly, it has no more meaning in that ancient language than it does in Spanish or English. As with the origins of the Basques themselves, explanations abound, ranging from a reference to pelota to the sound of sizzling olive oil. As with many Basque words, the orthography became almost a question of personal preference. Pil-pil with a hyphen was often used, and a 1912 book called it pirpir, one in 1919 said pin pin, and one in 1930 wrote of pirpil. The 1892 General Dictionary of Cuisine published in Madrid defined “pil pill” as “the name of a new red sauce the Bilbaíno gastronomes have invented now to eat with their famous chipirones, or squid:” The only explanation for this definition is that it was neither the first nor the last time a Madrid publication got its Basque facts wrong.

All of these variations on the name lend credence to the theory that the word is an onomatopoeia attempting to capture the sound of sizzling olive oil. An 1896 book, Lexicón Bilbaíno by Emiliano Arriaga, stated that the dish while cooking made the sound “bil-bil” but that, since there is a tendency to transpose ps and bs, which he also stated is the origin of the name Bilbao, the sauce became known as “pil-pil.” The only problem then is that pil pil doesn’t go “pil pil” anymore.

At some point later in the century, it was discovered that if the cooked salt cod was placed in an earthen casserole with warm but not at all sizzling oil and garlic, and the casserole was moved in a circular motion over a very low heat, the oil would thicken into a creamy, opaque, ivory-colored sauce.

The people of Bilbao like to say that the chefs of San Sebastián are French influenced, and though this may sound appealing to the outside world, especially the French, it is not intended to be a compliment. But the unpleasant truth is that in the late nineteenth century, Bilbao chefs were developing a number of sauces for their salt cod, because sauces were the fashion in French cuisine.

Nevertheless, this particular sauce was brilliant. Called ligado, meaning “bound” or “thickened” in Spanish, it had more craft and more originality—and more mystery—than the older, sizzling, clear-oil pil pil. Today almost no one makes the original pil pil, whereas ligado is considered the litmus test of a Basque chef. But apparently everyone still liked to say “pil pil,” and it has become the name for the thickened, ligado sauce.

There is a sense of alchemy to the emulsification of a good pil pil. It happens slowly as the casserole is being moved, the low temperature perfectly maintained, a little—not too much—of the water the fish was cooked in added to make more liquid. This is not a mayonnaise; there is no solid suspended in the oil. It is a sauce made purely of liquids, some of which somehow become solidified and suspended in the remaining liquid. There is not even a change in temperature. In fact, most cooks agree that all parts of the pil pil should be maintained at the same constant tepid state.

That is one of the few things agreed on. As with all Basque salt cod dishes, almost no one agrees as to how and for how long to soak the dried fish. Then, some insist it must be made in an earthen casserole or the emulsification will not take place. Many claim the secret is “in the wrist,” that is, in the correct circular motion of the cook’s arms while holding the casserole. Most recipes make a point of insisting on only the best-quality virgin, cold-pressed olive oil, but some cooks whisper that a few drops of corn oil helps the emulsion. But no Basque chefs would ever go on the record with corn oil in their pil pil.

The gelatin in the cod skin may be what creates the emulsion. In any event, pil pil would not be made without skin because to a Basque, a skinless salt cod is a deep offense. It has been discovered, some accounts say it was at the Restaurant Bermeo in Bilbao, that a sauce made with leftover skin and bones and then poured over the fish has a stronger bind.

The sauce is often described as a “triumph” of Basque gastronomy, but it is a triumph that was born of defeat. Bilbao put up a determined resistance and the siege was a disaster from which the Carlist cause never recovered. Bitter sentiments endured for more than a century, but both sides recognized that the siege of Bilbao gave the Basques a great sauce.

JENARO PILDAIN of the Restaurant Guria in Bilbao is considered one of the masters of pil pil. His technique is unusual in that he cooks the fish directly in the oil and not in water beforehand. Pildain learned pil pil from his mother, who had a country inn in the 1930s, and her technique may date back to the original pil pil sauce, since the recipe begins that way and then develops into the ligado sauce.

PIL PIL

(for six)

12 pieces of top-quality salt cod

4 cloves garlic

2 red guindilla peppers

Soak the salt cod for between 36 and 44 hours. During this time, change the water every 8 hours. Taste to see if this period of time has been long enough for the fish to be perfectly desalinated. Remove the desalinated salt cod from the water and let it drain. Scale it well and remove the bones. Then place it skin side up in an earthenware casserole with abundant olive oil and garlic over a low flame, removing the garlic when it has been browned. If the salt cod is top qualiy, 5 minutes cooking will be sufficient. When done, remove the olive oil and begin to move the salt cod against the casserole in a circular rolling movement and add, little by little, the oil that was removed until the sauce is thick, ready to be served.

Decorate with garlic that has been fried in oil and with sliced rounds of guindilla.