I am tempted to say about metaphysicians what Scalinger would say about the Basques: they are said to understand one another, but I don’t believe it at all.

—Nicolas Chamfort, French writer, 1741-94

SOON AFTER THE CARLIST defeat, disillusioned peasants in farmhouses on the green slopes above Bilbao looked down and saw an eerie red glow tinting the night sky along the Nervión River. That strange man-made volcano told them the world was changing— all the more reason to fight for the old ways.

A revolution was taking place in the cities and even some towns of Guipúzcoa and Vizcaya. Aside from these urban Basque regions and parts of Catalonia, the great changes of England, Germany, eastern France, and the northern United States—the industrial revolution—were not reaching Iberia.

The defeat of the Carlists and dismantling of the Fueros had presented Basque industrialists with an opportunity. When the Basque economy was focused on trading between Latin America and Europe, being outside the Spanish customs zone had been a great advantage. But while Basqueland was mired in the First Carlist War, Britain had revolutionized metal making by fusing coke and iron to produce steel, which destroyed the iron industry of Vizcaya that had once been a world leader. As the British eroded the Basque competitive edge for industrial products in Europe, and Latin American colonies became increasingly rebellious, the Basques were beginning to find the internal Spanish market attractive, especially since the population of Spain almost doubled during the nineteenth century. Once Vizcaya was inside the Spanish customs zone, the Basques were in a position to dominate the Spanish market against foreign competition.

In 1841, the same year that Basque autonomy was dismantled, the first blast furnace was built in Basqueland at a steel plant called Santa Ana de Bolueta. This one plant produced as much steel as 100 of the small mills that had been operating in Vizcaya. In 1846, Ibarra Hermanos, a leading Basque iron mining company, built the first completely modern Basque steel mill, Fábrica de Nuestra Señora de la Merced, down the Nervión River from Bilbao. In 1855, the Fábrica de Nuestra Señora del Carmen was built on the left bank of the Nervión.

In 1856, Henry Bessemer, working in Britain on an improved artillery shell, found that by blowing air through molten iron, he could speed up the process of converting iron to steel. No longer requiring tremendous time and energy, the new Bessemer converter process made steel cheap enough to be a practical metal for common use.

Ninteenth-century steelworkers in Vizcaya. The fact that they are wearing canvas espadrilles on their feet while working with molten metal is an indication of the safety standards for workers at the time. (Kutxa Fototeka, San Sebastián)

Bessemer had by chance used for ore a low phosphorus iron called hematite, and it was later discovered that this was a requirement for the Bessemer process to function well. There was only one place in Europe that had known deposits of this type of ore in easily exploitable fields near a coastline for efficient transport: Vizcaya.

A rail line was built from the mines to the coast, and the port of Bilbao was modernized. Confident that iron exports could generate enough capital to build Basque industry, the new infrastructure was financed with public money. The smaller mills merged into Altos Homos de Vizcaya, Vizcaya Blast Furnaces, which by the end of the nineteenth century was the largest steelmaker in Spain and one of the largest in the world. By exporting iron to England, Basque mills were able to get advantageous arrangements for British coal, which was the return freight From 1885 until the early twentieth century, Vizcaya produced 77 percent of Spain’s cast iron and 87 percent of its steel. With the ability to manufacture the cheapest steel in Europe, the banks of the Nervión from Bilbao to the sea, once a world capital of shipbuilding, became one of the world’s great steel centers, creating enormous wealth and thousands of jobs. Basques also invested in chemical factories, and in 1878 one of the first oil refineries in Spain was built on the Nervión.

There have always been two kinds of Basques. While some were fighting for the Basque way, the Basque tradition, other Basques, naming their steel mills after saints, just as they used to name the ships in their commercial fleets, fought for a place in the forefront of modern industry and became very wealthy.

These industrial Basques did not want serene isolation in their mountain lairs. They wanted rail connections to move raw materials, manufactured products, and people. These Basques wanted to be physically connected to Spain, which to them was nothing more or less than a market. In 1845, a rail link was completed between Irún, Guipúzcoa, on the French border, and Madrid. In 1863, a line from Bilbao to Tudela connected Vizcaya, Guipúzcoa, and Navarra. Both the railroads and the industries were financed by investments attracted from England, France, and Belgium. Basqueland was no longer to be a rugged enclave of isolated valleys.

The Basques were not only the leading industrialists but also the first modern bankers in Spain, providing the capital for growing industry. First came insurance companies in Bilbao, which underwrote shipping. In the 1850s, new laws allowed joint stock companies to finance banking and railroads. In 1857, the Banco de Bilbao was founded by the leading industrial and commercial families of the city to finance industry and infrastructure. Though hailed as a great success when it opened in 1863, the Bilbao-Tudela train line was bankrupt three years later, and the intervention by the newly formed Banco de Bilbao averted a severe economic crisis. In 1868, the Banco de San Sebastián was created. The Banco de Vizcaya invested in hydroelectric companies that controlled rights to the Ebro and not only provided for Bilbao’s energy but that of Barcelona, Santander, and Valencia.

The reason Marx admired Carlists and not Liberals is that Carlists were profoundly anticapitalist, the sworn enemies of the new banking and industry. Rural Basques could see the new capitalist class profiting on the loss of Basque privileges. The moving of the customs zone to the French border had gready profited Basque banking and spurred the creation of Basque industry. Carlists were appalled by bank and industry efforts to attract foreign investment. They saw foreign banks such as Crédit Lyonnais opening branches in San Sebastián and British engineers taking over mines. Vizcaya’s huge iron deposits were noted as long ago as Roman times, when Pliny wrote of a mountain “composed entirely of iron.” But this source of wealth was not inexhaustible, and only 10 percent of Vizcayan ore was going to Basque steel mills. The rest was being shipped abroad, 65 or 75 percent to British steel mills, which was contrary to Foral tradition. For centuries the Fueros had regulated iron mining as Basqueland’s most valuable resource, forbidding the exploitation of Vizcayan iron by non-Basques.

The Carlists were vehement anti-Communists, but they were among the first to speak out against the mistreatment of industrial workers. V. Manterola wrote in his Carlist newspaper, La Reconquista, “The factory worker is a virtual slave, turned into a machine by Liberalism, good only to produce, but without regard for his morale.”

IN 1869, THE Spanish government instituted secular marriage. In giving the state, rather than the Church, the right to create families, the government was shifting the fundamental control over Basque society. The family was the primary Basque institution, not only socially but economically, since most farms, stores, and businesses were family run. Even today, a high percentage of Basque businesses are family operations.

That same year, freedom of religion became law. No longer would Catholicism be the only legal religion in Spain. During debate in the legislature, the Cortes, it was pointed out that “the Jews descending from Spanish families, in London, Lisbon, Amsterdam, Bordeaux, and other parts of Europe, will want to return to Spain where their ancestors are buried, in the expectation that the elected Cortes has given them the freedom to practice their religion.” The Carlists warned that there could soon be mosques, synagogues, Buddhist shrines, and protestant churches in Spain and that the Jews and Muslims would take control of business and Spain would lose “not only its religion but its money.”

In 1872, a Basque Carlist rebellion financed by provincial Foral governing bodies grew into the Second Carlist War. The Banco de Bilbao funded Liberal forces to fight the Carlists. It was to be yet another war of Basque against Basque.

The two sides battered each other from 1872 to 1876, each side losing 2,000 men over Bilbao alone. The Liberal troops fighting for a secular state burned churches and monasteries, while Carlist forces torched town halls and civil records.

The Carlists established their own state in territory they held, crowning Carlos “king of the Basques” and establishing schools and other institutions, even issuing their own money and postage stamps. But in the end, once more, the Carlists lost. Their grandchildren would be the next Basques to have a taste of self-government.

The law of July 21, 1876, ended the remaining Foral rights. Now the Basques would not even have the right to manage their financial affairs. They would pay taxes to the Spanish government and be required to serve in the Spanish military.

TO THE BASQUES, culture has always been a political act, the primary demonstration of national identity. One of the keys to Basque survival is that political repression produces cultural revival. The loss of independence in two Carlist wars produced a conscious effort at a cultural rebirth known as the Basque Renaissance. Arturo Campión (1854-1937), a Navarrese writer on the myths and culture of Navarra, in 1884 produced a landmark work on Euskera, Grammar of the Four Dialects. Campión wrote that Euskera “is the living witness which guarantees that our national independence will never be enslaved.”

In 1891, Resurrección María Azkue, son of a noted poet, wrote a major book on Euskera, Basque Grammar, and went on to write an Euskera-French-Spanish dictionary and numerous other pivotal works on the Basque language. He also gathered folk songs and myths, village by village, to use as subjects for huge choral works. He was returning to a tradition started in the fifteenth century by a Guipúzcoan choral master, Johanes Antxieta, who arranged ancient Basque songs for choral works. The Basques are noted for their love of singing. On chant comme un Basque, You sing like a Basque, is a French expression for someone who sings loudly, well, and often. By the turn of the century the Basques were again singing like Basques, asserting their Basqueness in choruses that were larger than ever before, performing booming choral works in Euskera for soaring sopranos and chocolaty basses. Choral groups were established in Pamplona, Vitoria, Bilbao, and San Sebastián. The Orfeon Donastiarra, the San Sebastián Lay Choir, founded in 1897, and the Bilbao Choral Society, started the following year, are still performing.

Choral group in St.-Jean-de-Luz. (Collection of Charles-Paul Gaudin, St-Jean-de-Luz)

To the Carlists, and to many other Basques, preserving Basqueness was the first step toward regaining the Fueros. It was this concern about the Basque past that led to exploring prehistoric caves—such as Santimamiña cave, found in Vizcaya in 1917—for drawings and artifacts from the Paleolithic Age. Prehistoric discoveries led to assertions about the ancient Basque people in numerous tracts and books written by both French and Spanish Basques. In French Basqueland, that underdeveloped corner of France, ignored by the industrial revolution, where sons whom the farms could not support immigrated to America in large numbers, this cultural reawakening, especially a fascination with the ancient Basque past, was embraced. The invention of Aïtor, the father of the Basques, by Augustin Chaho, who was born in Soule in 1810, was typical of the kind of creative mythologizing of the period.

But of even greater interest on the Spanish side was the recent past The Fueros became the great martyr of Basque Carlism, and their restoration, a sacred cause. The hymn of a new Basque militancy, “Gernikako Arbola,” The Tree of Guernica, became to the Basques what the “International” was to Communism, or the “Marseillaise” to the French Revolution. From the Middle Ages until 1876, Basque leaders had met in front of the oak tree at the edge of Guernica. Once the Basques agreed to live under the monarchs of Castile, each king had been obliged to come to Guernica to stand under the tree and pledge continuing support for the Fueros.

Until the nineteenth century when the Fueros were threatened, the meeting spot was a simple place consisting of the tree and an old church. In 1826, a new pillared, neoclassical Batzarretxea, or meeting house, was built. In 1860, the then-300-year-old oak tree died and was immediately replaced with an offspring that still stands there. José María Iparraguirre, a Carlist volunteer in the first war at the age of thirteen, wrote “Gernikako Arbola” in 1853. He would sing it in unrestrained Euskera with his guitar in cafés. It begins:

The oak of Guernica. (Sabino Arana Foundation, Bilbao)

| Gernikako arbola | O tree of our Guernica |

| de bedeincatuba, | O symbol blessed by God |

| euskaldunen artean | Held dear by all euskaldunak |

| guztiz maitatuba. | By them revered and loved. |

| Eman ta zabalzazu | Ancient and holy symbol |

| munduban frutuba, | Let fall thy fruit worldwide |

| adoratzen zaitugu | While we in adoration gaze |

| arbola santuba. | on thee our blessed tree. |

Spanish authorities responded to the growing popularity of the song by arresting Iparraguirre in Tolosa and expelling him from Spanish Basqueland.

IN 1872, DURING the Second Carlist War, modern Basque nationalism may have accidentally begun when Santiago Arana, a passionate Carlist from Vizcaya, hid a wounded Carlist general, Francisco de Ullíbarri, in his shipyard. Arana was a wealthy industrialist who had purchased arms for the Carlists. When the Liberals learned of the general and the arms, Arana was forced into hiding, abandoning his wife and eight children. Then, fearing capture and interrogation, the family also went into hiding, eventually fleeing to French Basqueland. Sabino, the youngest child, was only seven years old.

Though the family was reunited at the end of the war, life was never the same for the Aranas. Sabino grew up with the weight of the Carlist defeat, a disintegration of family life that had only begun with separation and exile. Santiago’s bitterness over the defeat and the abolition of the Fueros made him seem physically and spiritually diminished. Even the family business, shipbuilding, was declining. Basque shipbuilding had reached new heights after the First Carlist War. With the new steel mills along the Nervión, the industry adapted to steel. Huge new shipyards such as La Naval were established along the riverfront. But the Arana family was still building wooden ships.

The two youngest children, Sabino and Luis, were sent off for a Jesuit education. Sabino would later write, “When I was ten years old I felt intense patriotic feelings, only I didn’t know what my country was.” He questioned why his father had so spent himself on Carlos, a would-be king of Spain. In 1882, according to Sabino, the two brothers were passing the morning talking in the garden, and they slid into a debate. Sabino championed the Carlist point of view, but Luis, echoing the forgotten argument of the slain Carlist Jose Antonio Muñagorri, thought the cause of Don Carlos had nothing to offer Basques. “Vizcaya is not Spain,” Luis argued to his brother. This was a deep revelation to Sabino.

The following year, their father as well as an older brother died, and Sabino drifted into a deep depression from which he emerged with an intense interest in the study of Euskera. He wanted to write a book on Euskera grammar, Elemental Grammar for Vizcayan Euskera, which could be used to teach the language. He also became convinced that Basques needed to study “the glory of their past in order to understand their current degradation.”

But, to please his mother, he studied law in Barcelona. As soon as she died, in 1888, he left law school and returned to the family estate in Vizcaya. That year a professorship of Euskera was created at the Instituto Vizcaíno, and Sabino applied. The winning candidate was Resurrección María Azkue. In second place, was Miguel de Unamuno. Sabino Arana had not attracted a single vote.

FOR TWO MEN who are almost perfect opposites, Sabino Arana y Goiri and Miguel de Unamuno y Jugo had a great deal in common. Both were deeply religious, and both saw the loss of the Fueros, the cataclysm that darkened their childhood, as the great tragedy of their times. Like Arana, Unamuno was devoted to issues of the Basque language and identity. His first book, his university thesis, was Critique on the Issue of the Origin and Prehistory of the Basque Race. His early dream, never realized, was to write a twenty-volume history of the Basque people. Both men were born in Vizcaya, Unamuno in Bilbao in 1864 and Arana the following year in a nearby town. The town and the city, Carlism and Liberalism. But in the beginning they did not seem so different. Perhaps their clash was heightened by the fact that neither man was much given to humility.

When older, Unamuno said that in his youth he had been a “staunch nationalist.” He used the Euskera word, bizkaitarra, that Arana had given to his journal, the first Basque nationalist publication. But it was clear even in his university thesis at age twenty that Unamuno was not a bizkaitarra. He was too honest an intellectual to be a true crusader. He was a contrapelo, someone who liked to comb his hair against the natural flow. In his Critique, he attempted to expose the romantic half-truths, the preposterous myths about Basque origin. Later he would write an essay titled Ideocracia about the tyranny of ideas. He declared himself an “ideophobe” who never wanted to see his thoughts turned into a movement.

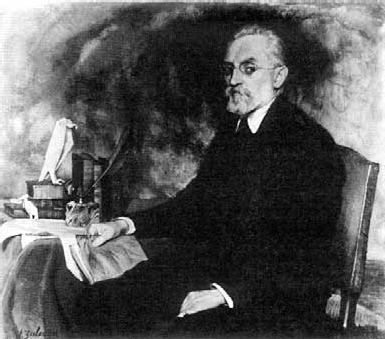

Sabino Arana did not suffer from this fear of ideas. The tyranny of ideas was to be his kingdom. He did not want to expose myths; he wanted to create them. While Miguel de Unamuno is remembered as one of the greatest intellectuals Spain has ever produced, Sabino Arana was a fanatic, perhaps a lunatic, certainly a racist, and a man who spent his life in a hotheaded fury, dying young and absurdly. During a half century Unamuno produced a large body of work, including novels, poetry, and essays; Arana’s few writings are seldom read, and he is rarely spoken of with fondness even by his supporters. Yet it is Arana, not Unamuno, who has had the great impact on history. That is partly because Arana, unlike Unamuno, did want to start a movement.

Sabino Arana. (Sabino Arana Foundation, Bilbao)

The more Unamuno reflected, the more he turned against Basque nationalism, which he called, in his first novel, Paz en La Guerra, “exclusivist regionalism, blind to all broader visions.” Typical of middle-class Bilbao, he became a Liberal, and remained one even after that movement had become, by his own admission, irrelevant. He was always proud of his Basqueness, but he concluded that Basques were simply an interesting and valuable element in the greater quilt that was Spain. He regarded Euskera as an inferior language to Spanish, an oral language of peasants, unsuitable for literature, and claimed that agglutinating languages were not capable of articulating sophisticated ideas.

Contemporary writers have proven Unamuno wrong about Euskera. He failed to see how the Basque Renaissance could change the language. Until then, Euskera had not been used as a literary language. But in 1898, a priest named Domingo de Aguirre wrote the first novel in Euskera, Aunamendiko Lorea (The Flower of the Pyrenees), a romantic historical story set in the seventh century.

Arana was that dogmatic nationalist, “blind to all broader visions,” that Unamuno had described. He had a single idea: that the Basques were a nation and should have a country. In fact, so narrow was his focus that originally he spoke only of his native Vizcaya. But Arana instinctively understood nation building. He reflected on why his nation was not a country and resolved to give it the missing elements. He gave it a name, inventing the word Euzkadi from Euskal, meaning “Euskera speaking,” and the suffix di, meaning “together.” Before this, Euskera had only the phrase Euskal Herria “the land of Euskera speakers.” Euskal Herria was the name of a place, but Euzkadi was intended to be the name of a country. Arana invented other important words in Euskera: aberri, meaning “fatherland,” from aba, meaning “father,” and erri, meaning “country”; abertzale, meaning “patriot”; and azkatasuna, meaning “liberty.” He not only invented new words but changed the spelling of existing ones, to make them look more Basque. The Castilian c was replaced with the Basque k and the s with z. He gave Euzkadi a mythology of national origin in works such as Bizkaya por su Independencia (For Vizcayan Independence), which mythologizes the medieval struggle for independence of the Basques.

Bizkaya por su Independencia, originally published in 1890 as Cuatro Glorias Patrias (Four Glorious Acts of Patriotism), is considered the founding act of modern Basque nationalism. Critics argue that it was founded on a lie; supporters would call it simply an embellishment.

Compared with other Basque writing of the nineteenth century, such as Chaho’s invention of Aïtor, these four stories of great battles in Vizcaya between the Basques and León and Castile were not outrageous. Arana was not as interested in historical facts as he was in turning these events—the battles of Arrigorriaga in 888, Gordexola in 1355, Otxandiano in 1355, and Munguia in 1470— into epic struggles for the founding of the Basque nation. Complications such as those other Basques, including the Loyolas, who were ready to fight to the death for Castilian privileges, were not to be part of the founding myth. Arana was a propagandist, not a historian, and he understood the importance of simplicity. This was a Basque declaration of independence.

The book ends by asserting that “Yesterday,” each of the four places:

fought against Spain, which tried to conquer it, and remained free. Today—Vizcaya is a province of Spain Tomorrow— . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ?

Heed these words, Vizcayans of the nineteenth century, the future depends on what you do.

ON JUNE 3, 1893, Arana organized the first public demonstration openly declaring Basque nationalism. His early supporters were mostly young men under twenty-five years old, but his following grew at a rate that sometimes alarmed his adversaries. On July 31, 1895, Ignatius Loyola’s Saint’s Day, Arana officially founded the Basque Nationalist Party, his underground independence movement.

Arana wrote the Basque national anthem, “Gora ta Gora,” though it was set to music only after his death. He worked with his brother Luis on designing the flag, the ikurriña, originally for Vizcaya and later as the flag of Euzkadi. The flag established the Basque national colors: red, green, and white. Typical of Arana, the reasoning behind the flag’s design was arcane and alienating, but the reality of it is appealing. According to Arana, the red background symbolized the people, the green x stood for the ancient laws, and the white cross, superimposed over it, symbolized the purity of Christ But what makes the ikurriña work is that it echoes the colors of Basqueland, recalling a red-trimmed, whitewashed Basque house set against a lush green mountain.

ACCORDING TO ARANA, ninth-century Basqueland was “a confederation of republics . . . free and independent, harmoniously and fraternally united.” But, like many sons and daughters of old Carlist families, Arana exaggerated the democratic quality of the Fueros.

In some ways, the Fueros were remarkably progressive for medieval law. The revision written in 1526 under Guernica’s oak tree was one of the first legal codes to outlaw the use of torture. It was also one of the first European codes to ban debtors’ prison. It protected citizens from arbitrary arrest and unwarranted house searches. But contrary to what is often asserted, traditional Basque government was not a representative democracy. It favored rural people and did not give proportional representation to urban dwellers. The code did not give full rights to women but gave women more consideration than most medieval law. For example, inheritance law emphasized keeping an estate intact and favored surviving widows. An older sister had priority over a younger brother. The Fueros were sympathetic to family-owned business and small holdings. When Socialist-led democracy came to power in Spain in 1982, wanting to rewrite property laws to break up large holdings, it looked to the Basque Fueros for a model of property law.

In any event, Arana, who touted the Fueros as the perfection of democracy, did not have a notably high standard of democracy. His ideal was closer to a Catholic theocracy, a notion which traces back at least to 1881, when he was fifteen and had fallen so ill that he was given last rites. Miraculously, he recovered, and ever after he credited the Virgin Mary with this unexpected reversal. His slogan for the Basque Nationalist Party, a motto which is still used, was Jaungoikua eta Lagizarra, God and the Old Laws, today frequently abbreviated on official Basque Nationalist Party messages as JeL.

Arana wrote that if the Basques were ever to abandon the Church, he would abandon the Basques. He called for Euzkadi to be “an essentially Catholic state” and added, “It will not admit in its midst any individuals affiliated with a false religion, sect, schism, masonic or liberal.” In 1888, when he was twenty-three, he learned that a London-based Bible society had obtained permission to sell Protestant books in Bilbao. He applied for permission to distribute Catholic literature next to them, giving his away without charge, until he drove the Protestants out of Bilbao. As for Jews, on the occasion of the death of French writer Emile Zola, Arana wrote a profile describing the hero of the infamous Dreyfus case as “el nuevo Judas who got filthy-rich by using his pen to help Jews fight Christ.”

ARANA WAS ONE of the first Basques to address a question destined to plague Basque nationalists forever: Who is a Basque? This was an especially contested issue in his epoch because, for the first time in history, a large percentage of the population of Basque country did not come from Basque families. Vizcaya had a labor shortage soon filled by the poor of Spain.

This new and different kind of invasion was one that history had not prepared Basques to face. From 1857 to 1900, the population of Alava grew by only 2.5 percent, which was about the same growth as Navarra. But during the same period, Guipúzcoa’s population grew by 25 percent and Vizcaya’s by almost 94 percent. For the first time in history, more people were moving to Vizcaya than leaving it.

This immigration to industrial areas tended to further exacerbate the differences between rural and urban life. The countryside was remaining Basque, while the cities were becoming cosmopolitan. In 1850, the population of Bilbao was 20,000. By the end of the century, the population had grown to almost 100,000, more than half of the residents born outside Vizcaya. Some of these outsiders—British, Germans, and other northern Europeans— were entrepreneurs, managers, and supervisors who came with foreign capital. They had a huge impact on the cultural life of Bilbao, especially the British. The Athletic Club of Bilbao, Vizcaya’s now-much-loved soccer team, was founded and trained by the British in 1898. Even Arana’s ikurriña was modeled on the British Union Jack.

But the great majority of the new residents were workers from Andalusia and other poor regions of Spain. The new wealthy Basque industries were creating jobs that drew desperately poor people. They lived near the mills in dark, crowded housing, often provided by the companies, worked long hours, earned little money, and spent it at company stores. They had no better choice, coming from places that had no work and nothing to eat. Working twelve hour days, breathing black smog, they died young of lung disease or alcoholism.

An underclass was being created in Basqueland, and Basques sneered at it the way societies usually do at poor immigrants. Basques emphasized the foreignness of these workers by referring to them as Chinese, Manchurians, or Koreans. Another popular expression was maqueto, later translated into Euskera as maketo. This was one of Sabino Arana’s favorite words, and, having a Basque explanation for most everything and a creative approach to linguistics, he theorized that it came from makutuak, which he said was an Euskera word meaning “those with bundles on their back.” However, magüeto is a pre-Roman word from northern Spain meaning “outsider,” and the Greeks used the word meteco to mean “outsider.” In 1904, Unamuno wrote, “With mines and industry facilitating the accumulation of great wealth, now is when a change in spirit can be noted. Enterprising and active, yes, but it has made the Bilbaíno unbearable, with his wealth convincing him that he is of a special superior race. He gazes with a certain petulance at other Spaniards, those who are not Basque, if they are poor, calling them contemptuously, maquetos.”

If racism is not clear by the use of this word, another Basque term for foreign workers, belarri motx, stumpy ear, leaves little doubt. One of the peculiar characteristic of Basques is their long earlobes. But stumpy ear was not a term of endearment. In the 1870s there had even been a soldier’s song among the Basque Carlists that included the line:

eta tiro, eta tiro/belarrimotxari

And shoot, and shoot/at the stumpy-eared ones

Arana had several objections to the Stumpy Ears. Until they came, the great majority of the population had spoken Euskera; now, these Spanish workers and their families were turning it into a minority language. This was only the most obvious example of how the Basque culture was being diluted. The Stumpy Ears were also less religious than the Basques, and they were increasingly involved in that anathema antireligious movement—socialism.

Arana’s attempts to define who is a Basque make apparent the racist nature of his vision. He declared that for people to be considered Basque, their four grandparents must all have been born in Euskadi and have Euskera names. If married, true Basques must have spouses of similar purity.

This view was not entirely removed from Basque tradition. Normally, to be eligible for a Spanish title of nobility, a family was required to obtain a certificate of “blood purity,” which proved that the family had no Jewish or Moorish blood. But since Vizcaya had never been controlled by the Moors, the Spanish waived the requirement for Vizcayans. To preserve this status, the Basques had established rules to bar outsiders from settling in Vizcaya. Of course, as with many Basque laws, there was also a commercial angle: It kept outside competitors from setting up shop in the province.

Arana and his Basque nationalism, like Carlism, idealized peasants, though the ideologues themselves were rarely of peasant background. Basque culture is, in many ways, rural. The etxea, facing the sunrise with the Basque solar cross over the doorway, is a rural concept. And so traditional Basques, even if they live in a city, make reference to a rural origin when they introduce themselves by the name of their ancestral house.

In 1900, Arana married a peasant, Nicole Atxika Iturri, who had little education and little chance of understanding her husband. But Sabino pointed out that his bride fulfilled his definition of Basque with her two Euskera family names. To him, this marriage was a perfect symbolic act, and Sabino cared far more about symbolism than reality. Instead of applauding his uncompromising beliefs, some in the movement feared the cause of Basque nationalism would be harmed by this mismatch. But while everyone else saw an uneducated impoverished girl from a farm, Sabino saw that great institution, the Basque peasant. He protested to a friend, “She is an original Vizcayan—all of the original Vizcayans descend from nobility, all Basques descend from villagers, farmhouses.”

Marriage to Sabino, however, was not to be a peasant’s fantasy of marrying into the upper class. He ordered his original Vizcayan to cloister herself in religious contemplation to prepare for the marriage. For a honeymoon, he took her to Lourdes, the Catholic shrine near French Basqueland where thousands of infirm peasants flocked for faith healing.

Soon came an event in the life of Spain and the Basques, of Unamuno and Arana, of singular importance. Americans call it the Spanish-American War, but in Spain it has always been known as El Desastre, the Disaster.

THE SPANISH-AMERICAN WAR, the Disaster, the Cuban War of Independence—it was a different war for different people. But only the United States won. Though the war’s boosters in America had promoted it as the war to rescue poor Cuba in its noble struggle against Spanish tyranny, once the new territories of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines were taken by military force, the United States had little interest in setting any of them free. In fact, the United States granted Puerto Rico and Cuba less self-government than the Spanish had offered. The new territories were, to the Americans, delicious war booty. Books with titles such as Our New Possesions excitedly introduced these prizes to the American public. Meanwhile, the Spanish public had to adapt to suddenly being without these places, the last of the empire that they had known for four centuries. Spain had lost the lands won by Columbus, Magellan, Elcano, and all the other great men reproduced in stone and bronze. The places with which they traded, the places to which a Spaniard went to seek a fortune or adventure, the places to go when things went wrong in Spain, the places that were Spain’s claim to being a world power, were gone.

This disaster produced the greatest flow of literature Spain had seen since the period from the mid-fifteenth century to the late sixteenth century known in Spanish literature as the golden age. The new turn-of-the-century writers and artists were called “the generation of ‘98,” a group who responded to El Desastre by seeking to analyze and redefine the newly diminished Spain. Through paintings, novels, poems, and essays, they searched for the essence of Spain in Castilian landscape, in the history of the golden age, in critical examinations of classic literature such as Cervantes’s Don Quixote de la Mancha. The pivotal question was: How can Spain undergo a regeneration?

Miguel de Unamuno by Ignacio Zuloaga (1870-1945). Born in Eibar, Zuloaga, with his dark vision of Spain, was one of the leading painters in the generation of ‘98. (The Hispanic Society of America, New York)

Curiously, this search for the soul of Spain was led by Basques. Experiencing the Spanish simultaneously as both “us” and “them” is essential to discovering the soul of Spain. Castilians, for whom Spain is only “us,” are the exception. Unamuno was a central figure in the generation of ‘98, as was San Sebastián-born Pío Baroja, the doctor-turned-novelist. Lesser-known members of the group, such as Ramiro de Maeztu, were also Basque. A number of the central figures were non-Basque, notably philosopher José Ortega y Gasset and poet Antonio Machado. But even most of these non-Basque writers were not from the Castilian heart of Iberia. Yet Spain, even Castile, was their focus.

It was not the focus of Sabino Arana, who referred to Spain as Maketania and said, “It doesn’t matter to us if Spain is big or small, strong or weak, rich or poor. They have enslaved our country and this is enough for us to hate them with all our soul, whether we find them at the height of greatness or the edge of ruin.” Arana’s followers sometimes shouted, even on the streets of Madrid, “Down with the army! Die Spain!”

In truth, the defeat of Spain, perhaps the sight of it shedding territory, inflamed both Basque and Catalan nationalism. It was at this moment in history that both the Basque and Catalan yearnings for nationhood, which had been romantic dreams, developed into serious political movements.

To those other nationalists, the Spanish nationalists, this was an affront never to be forgiven. Spain, the great nation, had gone down in humiliating defeat, and in this dark hour, the Basques and Catalans were attacking, hoping to further amputate the already truncated nation.

The defeated military developed a festering resentment of Catalans and Basques. At their urging, in 1900, the penal code was revised to categorize claims of separatism as acts of rebellion against the state. In 1906, such statements became “a crime against the army” and military justice was given jurisdiction over these cases.

Sabino Arana came to an end, absurdly testing this new and furious rift. In May 1902, he attempted to send a telegraph to Washington:

Roosevelt. President of the United States. Washington.

In the name of the Basque Nationalist Party, I congratulate Cuba, which you have liberated from slavery, most noble federation, on its independence. You have shown in your great nation, exemplary generosity, learned justice and liberty, hitherto unknown in history and inimitable by European powers, especially the Latin ones. If Europe were to imitate this, then the Basque nation, the oldest people, who, for the most centuries, enjoyed the kind of liberty under constitutional law for which the United States merits praise, would be free.

Arana y Goiri

The telegraph office, rather than send it, delivered the telegram to the appropriate authorities, who arrested Arana. Never a healthy man, he had often been arrested and survived short prison terms. But now, at thirty-eight, his health seemed to be finally failing. Arana’s supporters circulated a petition asking for his release and got 900 signatures. The response of a government official, Segismundo Moret, was “It would be more gallant to leave him die in prison. The peace of Spain outweighs the life of one man.” After almost a half year, his frail health ruined, he was released. Fearing further legal action, he fled through the Roncesvalles pass to St.-Jean-de-Luz. Finishing the writing of a play titled Libe, he went to Vichy in the hope that the waters would restore his health.

Arana believed that theater was second only to the press as the best vehicle for propaganda. Libe is the story of a woman who chooses to die, rather than be married to a Spaniard.

Only weeks after his release, Arana returned to his home in Vizcaya to die, which he did on November 25, 1903, at the age of thirty-eight. According to legend, his last word was “Jaungoikua,” God. On a rainy day he was buried in Sukarrieta, leaving no descendants. His wife remarried a Spanish policeman.

WHILE BASQUE NATIONALISM has grown, its detractors always find Sabino Arana the easiest of targets. Even most nationalists have few illusions about their founding father. Ramón Labayen, like his father and many other family members, a lifelong activist of the Basque Nationalist Party, said, “Sabino Arana was an unpleasant man with no sense of humor. A wealthy man who never worked a day for money.”

But Sabino gave the Basques their colors, a flag, a vocabulary, the name of their country, and the political party that would produce many of their future leaders. Though he himself remained a seemingly preposterous figure, he gave credibility to his movement by attracting significant numbers of followers. Ramiro de Maeztu, one of the Basque generation of ‘98, said of Arana’s success, “Unfortunately we can no longer say—and here I am on the side of the Madrid press—that separatism is just four nuts.”

It can be argued that it was the times, that between the end of the Fueros and 1898, Basque nationalism would have arrived even without this unpleasant zealot. What is certain, though, is that when Sabino was born, the Basques had a culture and an identity. Thirty-eight years later, when he died, they had the beginnings of a nation. A country was the great unfinished work.