If you do not teach your children the language of your parents, they will teach you.

—Sabino Arana, BASSERITARRA, June 20, 1897

THE MOST IMPORTANT word in Euskera is gure. It means “our”— our people, our home, our village. Cookbooks talk of our soups, our sauces. “Reptiles are not typically included in our meals,” wrote the great Guipúzcoan chef José María Busca Isusi. That four-letter word, gure, is at the center of Basqueness, the feeling of belonging inalienably to a group. It is what the Basques mean by a nation, why they have remained a nation without a country, even stripped of their laws.

Few Basques have made better use of the new nation than Bernardo Atxaga. Starting in the emerging Euskera publishing industry, and then having his works translated into Spanish and eventually, other languages including English, he has become the most widely read author in the history of the Basque language. His 1988 novel, Obabakoak, meaning “Things from Obaba,” is a cycle of stories centered on a fictitious Guipúzcoan village. As of 1998, it had sold 45,000 copies in Euskera, a considerable accomplishment in a language with less than 1 million speakers. The Spanish translation sold 70,000 copies, and it has also been translated into fourteen other languages.

Before Atxaga, it was rare for a writer in Euskera to be translated and almost unheard of for them to be translated into languages other than French or Spanish.

Between the first book published in 1545 and 1974, 4,000 books were published in Euskera. In the next twenty years another 12,500 were published. Atxaga said that he started in Euskera by reading Aresti, and three years later he had read every book in Euskera available to him. That would no longer be possible. About 1,000 titles are now published in Euskera every year, including novels, poetry, nonfiction, academic books, children’s books, and translations of classics and best-sellers.

For a very long time, publishing a book in Euskera was a purely political act. The first book entirely in Basque was a collection of both religious and secular poems published in Bordeaux in 1545, written by a priest, Bernard Dechepare, who made his intentions clear in the opening paragraph: “Since the Basques are smart, valiant and generous, and since among them are men well educated in all the sciences, I am amazed that no one has attempted in the interest of his own language, to show the entire world, by writing, that this language is as good a written language as any other.”

Modern Basque publishing began while Franco was in power. Elkar was created in 1972, established as a French nonprofit company based in Bayonne, with twenty small investors, including some Spanish Basque refugees. The little company produced records of popular music in Euskera that earned money to help finance book publishing. After the death of Franco, some of the refugees returned to Spain and established a second base in San Sebastián. With its twin bases, Elkar became the largest publisher of Euskera, but soon many others appeared. Some were financed by Vizcayan banks, the Basque Nationalist Party, or the governments of the three provinces or of Navarra.

A daily newspaper in Euskera was established, along with several weeklies, magazines, and children’s publications. Basque radio and television stations broadcast on both sides of the Pyrenees. The Basque government also supported a young film industry in Euskera.

In addition to the education of Basque youth, 100,000 adult Basques have learned Euskera since Atxaga began his career. The total market is still small. Atxaga recognized that as a great opportunity. “We have the advantage and disadvantage of scale,” he said. “We can do a lot of different things.” Not yet fifty, he had published more than eight novels, twenty children’s books, poetry, essays, and lyrics for his favorite rock band—all in his once forbidden native language. It is the enviable position of a leading artist in a very small country. The ubiquitous Eduardo Chillida is in a similar position, designing monuments in such defining spaces as the oak tree in Guernica, but also designing the logo for the amnesty movement and the trademark for Guipúzcoa’s provincial savings and pension bank.

Jorge de Oteiza, a generation older than the aging Chillida and a founding father of modern Basque abstract sculpture, has not seized these opportunities. The most important collection of his work is stacked on the floor of his studio in the Guipúzcoan coastal town of Zarautz, while he, the five foot tall, white-bearded, nonagenarian enfant terrible of Basque art, shakes his cane and rails against selling art for money. As he sits in his favorite Zarautz restaurant denouncing “the other sculptor’s” productivity, a metal plaque shines on the wall from the Kutxo bank, bearing their familiar logo, designed by Chillida.

Atxaga is an elfin man whose work always displays a mischievous humor. His popularity may come from being that old-fashioned kind of Basque who, although rooted in his little country, is an internationalist at heart. His writing makes references to American popular culture, to German politics, to the world at large.

On chance encounters with old friends and former schoolmates from his San Sebastián high school, they often greet him in Euskera, good mother-tongue Guipúzcoan, and for the first time he realizes that they had that language in common all along, though they had never dared to speak it to each other.

Many things have changed since those times. The young woman at Sarriko who invited him to “a cultural meeting” for Maoist indoctrination had left long ago and, in the late 1990s, was still a guerrilla in El Salvador. Another classmate was killed in El Salvador. One of the head Maoists at the university became an important technocrat in the Basque government working on tax policy.

An unpretentious man of simple origins, Atxaga is nevertheless aware of the absurd fact that he may be the Shakespeare of his language. What he does with Batua could well affect generations, possibly even centuries, of writers. Euskera literature is new enough to offer a creative freedom that few other languages could. With that freedom comes difficult choices. There are words in Euskera that are not in common usage, and he worries that they interfere with the narrative flow. Yet he does not want to limit the richness of the vocabulary. “I would say that the first duty of literary language is to be unobtrusive. And that is our weak point, because we lack antecedents.”

Ramón Saizarbitoria, though of the same generation with the same early influences, is almost the opposite of Atxaga. Born in 1944 in San Sebastián, he is seven years older. Atxaga’s stocky physique, friendly manner, and rumpled appearance suggest his upbringing in rural Guipúzcoa. Saizarbitoria, an urbane native of the most sophisticated Basque city, is tall, thin, impeccably dressed, with a carefully trimmed only slightly graying beard, a slow, careful manner, and a quiet, reflective way of speaking. While Atxaga lives in a village in Alava, Saizarbitoria lives in the heart of San Sebastián, with an office along a wide downtown boulevard that has long been favored for political demonstrations because its many escape routes make it impossible for the police to seal off.

While Atxaga struggled with the local authorities in his village for speaking his native Euskera, Saizarbitoria seldom had occasion to speak it outside of his home. In the San Sebastián of Saizarbitoria’s childhood, Euskera was the language of rural people who had immigrated to the big city, people like his parents. Nobody in his school spoke Euskera. “There were not even songs in Euskera. There was no need to prohibit it,” said Saizarbitoria. “People who spoke Euskera were suspected of being nationalists. But also there was a sense of shame in speaking the language of farmers and peasants and poor people.”

For years, nationalists struggled with this class image of Euskera as the language of peasants. The lower-class status of the language was often more image than reality. Many educated people spoke Euskera, and in some towns, notably the metalworking center of Eibar, Euskera was the language of both workers and management, a prerequisite for working in a factory even for an inmigrante from Andalusia.

Like Atxaga, Saizarbitoria found his inspiration in the invention of Batua and the works of Gabriel Aresti. Published in 1969, Saizarbitoria’s first novel, Egunero hasten delako (Because It Begins Every Day), was about abortion, which was legal in the rest of Europe but banned in Spain. The book’s subject and lean, carefully crafted prose launched a new genre in Euskera literature— the modern social novel.

His second novel was published after Franco’s death, in 1976. Titled 100 metro, 100 Meter, it relates the thoughts of an ETA suspect in the last moments of his life, chased a final 100 meters, before being shot to death.

Saizarbitoria was never an ETA activist, but he was a sympathizer he said, “like almost everyone.” He has remained resolutely political. “I want to defend my culture and my identity, and sometimes nationalism is the only possibility. When I am with nationalists I am against them, but when I am with others I am a nationalist.

JOSÉ LUIS ALVAREZ ENPARANTZA, known to most Basques as Txillardegi, is a professor of Basque philology, the sociology and linguistics of Euskera, at the San Sebastián campus of the Universidad de País Vasco, University of Basqueland. His baggy corduroys and akimbo hair display stereotypical professorial disorder. On his office wall is a 1914 “ethnographic map of Europe” showing areas where Basque, Irish, and Breton were spoken, Greek-speaking enclaves in Turkey, all the rebellious niches of European language. By the late 1990s, he had authored some twenty books, including essays on linguistics, a mathematical analysis of linguistics, five respected novels, and lyrical poetry.

Where now stands the icily white, contemporary campus of this disheveled professor, in 1929 was the rural neighborhood where he was born. The rebel is still there. Until 1998, he taught only in Euskera, and when the university insisted that it wanted to offer a course taught in Spanish, he refused, until it threatened to hire a second professor of Basque philology.

The promotion of the Basque language remains the first goal of most nationalists, and although huge strides have been made, there is still much to do. Most of the business of the Basque government is still done in Spanish. Although Euskera is a requirement for nonpolitical government jobs, many elected politicians, even from the Basque Nationalist Party, do not speak it. In 1998, many Basque politicians were angered because the proposed candidate for lehendakari, Juan José Ibarretxe, could not speak Euskera well.

The most visible language fight is over signs on the highway. Slowly, names are changing back to the Basque spelling. Many are easy to understand. Guernica in Euskera is Gernika. Bilbao is Bilbo. But San Sebastián is Donostia, Vitoria is Gasteiz, Pamplona is Iruña, Fuenterrabía is Hondarribia. The only solution that would not lead to thousands of outsiders getting lost on the highway is to do what any small country with an obscure language might do, print names in two languages. But for twenty years, vigilante nationalists have been spray-painting away the Spanish names. The result is exactly what was intended: Anybody who spends any time in Basqueland knows the towns by their Basque names.

“HOPE RISES FROM their hearts to their lips like a song from heaven,” wrote José Antonio Aguirre. “That is why the Basques are always singing.” Song is the oldest art form in Euskera and the most profitable one. Some of the large choruses founded in nineteenth-century nationalism are in fashion again. Benito Lertxundi’s acoustic guitar and protest songs have never fallen out of fashion. Trains, shops, and public buildings pipe in his music, including the old underground songs that teenagers used to whistle at Guardia Civil—daring to think in Euskera in front of them.

As in the 1930s, anything Basque is prospering, and that includes Basque sports. Basques are again attending the goat races and wood-chopping contests, the ports are again hosting ardently contested regattas, and the always popular pelota has more fans than ever before. They are not as drawn to the long-basket jai alai from St. Pée that Basques had popularized in the Americas, but to bare-handed pelota. Appealing to the same old-fashioned machismo as the wood chopping and other tests of strength, this sport uses two or four players, armed with nothing but their bare hands with which to smack a ball somewhat smaller than and just as hard as a baseball. Bare-handed matches have a quality of theater to the way they are played on three walls with the imaginary fourth wall opened to an audience. Since there is no racquet, it is an ambidextrous two-handed game. No athlete ever looked more naked than the bare-handed pelota player with no equipment but carefully placed bandages to protect the two bare hands. It seems the entire body goes into the hand as it slaps the hard little ball.

The many other variations of pelota with baskets and paddles of different sizes were designed to make the ball go faster, making it harder to return, but in a bare-handed match the point is scored by carefully setting up the opponent through the placement of the ball over a series of volleys.

The players used to come from families of players, and many still do. Retegi II, born in 1954, won championships almost every year in the 1980s and 1990s. Tintin III was another leading player. The numbers after their names indicate the number of generations of champions. Panpi LaDouche, the greatest champion from the French provinces, was trained by his father in the family court in the village of Ascain in the Nivelle Valley. His legal name is Jean-Pierre, because until recently, parents were not allowed to register their children’s birth certificates in France with a non-French first name.

Pelota ticket, 1928. (Euskal Arkeologia, Etnografia eta Kondaira Museoa, Bilbao)

One thing Basques in the 1970s could all agree on was that Panpi LaDouche was beautiful. His surprisingly agile, muscular body played the forward court with merciless precision. Though he was right-handed, his left hand could scoop the ball off the left wall, whip it across his body to the far corner of the front wall and up into the spectators’ section before his opponent could touch it. The move is called the gantxo. Panpi spent four or five hours a day at home with his father, a former professional, developing the left-handed gantxo. In 1970 he became the first man born on the French side to win both the French and Spanish championship.

The sport has become more popular and more profitable than ever because of television. The game is organized into clubs, empresas. Typically, an empresa will control fifty players and arrange matches between them. The empresa earns a percentage of the ticket sales and the betting. But in the 1990s, the empresas, like the players, were earning most of their money from selling broadcast rights to television. With television bringing much more money into the sport, professional bare-handed pelota players are no longer trained by their fathers but hire personal trainers, and, as in other professionals sports, the players are becoming stronger and faster.

But Basques work in families, and one aspect of this sport has remained that way: the balls. When an empresa arranges a match, it also chooses the balls. Down the river from Bilbao, past the shipyards and steel mills and the soot-blackened, crowded apartment buildings where a worker can stand on his cramped balcony and stare out at the smokestacks and grime belching from his factory, is Sestao. Like many blue-collar towns in Vizcaya, the center is marked by three things: a soccer stadium, a fronton, and a cemetery.

At the far end of the fronton, up a set of metal steps, is a six-by-twelve-foot room. This is Cipri, the “factory” where the world’s best pelotas, most of the balls chosen for professional matches, are made. Cipri is short for Cipriano. The first Cipriano Ruiz started making the balls in the nineteenth century. His son, also Cipriano Ruiz, began in the 1930s. In the 1990s they were made by the second Cipriano’s two sons, Cipriano and Roberto. Cipri never had employees, because the business depends on keeping secrets. When a manager orders balls, he tells them which fronton the match will be in. Each court has different walls and a different floor, and the Ruizes know all of them. The manager might have other requests. Make it fast, make it slow, have it bounce high, keep it low. The managers tell Cipri what kind of a match they want.

When the discovery of America was still new, the first balls were made of rubber. Today they are made of thin, clear, very stretchy latex tape. The tape is wound into hard little balls, which sit in old egg cartons awaiting the next step. Then they are wrapped in pure wool yarn, then in cotton string. When the ball is finished, a goat skin is stitched on in the same way as a horsehide on a baseball. The ball always weighs between 104 and 107 grams. Yet somehow each ball is built for a different performance. This is all the Ruizes will say. Explaining the secretiveness of Cipri, Panpi LaDouche, a native of the Nivelle Valley, said, “It’s like a good gâteau Basque.”

THE OLD BRITISH freight docks, a huge riverfront operation in the heart of Bilbao that had serviced British industry for more than a century, was closed down in the post-Franco economic restructuring, but soon farmers on the slopes above the city saw a strange new sight below. The metal was whiter and fresher than anything else on the riverfront. And it had the name Guggenheim.

How Bilbao ended up with a Guggenheim museum, paid for by Basque taxpayers, was a demonstration of the inner workings of the Basque Nationalist Party, the PNV. The project was a party dream, with nationalist motives that involved almost every imaginable calculation other than art. Josu Ortuando, mayor of Bilbao, said, “We were able to win out over Salzburg and other cities because city hall, parliament, and the Basque government could act as one.” Though it is not clear that the other cities wanted to win, what the mayor was referring to was the fact that all three levels of government were controlled by the PNV.

The Guggenheim Foundation, in financial difficulty, was shopping for a site to build a new Guggenheim, one that would not cost the foundation anything and in fact would generate revenue for it. Tokyo, Osaka, Moscow, Vienna, Graz, and Salzburg were among the cities that had already turned down this financially dubious proposition when the foundation director, Thomas Krens, heard of this curious thing—a Basque government. In the end, the Basque parliament, led by the Basque Nationalist Party, but in coalition with Socialists, approved the project. It was not so much the Basque government or the Basque legislature that was drawn to it as the Basque Nationalist Party. The key figure behind the scenes in the negotiations, the man whose thumb up or down was critical but who held no elected office, was Xabier Arzalluz, the Basque Nationalist Party boss.

The choice of Bilbao was in itself significant. Vitoria, the capital of Euskadi, was too provincial and geographically too removed from the Euskera-speaking heartlands to be considered. The cultural center of the three provinces is San Sebastián. But the headquarters of the Basque Nationalist Party is in Bilbao.

The Basque Nationalist Party, now a century-old institution, is the central and anchoring power in Euskadi. The largest political party, it likes to operate as though it were synonymous with government itself. The ikurriña, the official flag of the Autonomous Basque Community of Euskadi, is also the official flag of the party. Often, the sight of the flag means nothing more than a local party headquarters.

The main headquarters in Bilbao, with its especially large ikurriña, is a modern structure of Stalinist grandeur with two thick, dark, black pillars supporting nothing on either side of a metal detector. It was built in 1993 on the site of Sabino Arana’s house, literally Sabin Etxea, and it is where Arzalluz’s office is located.

Once you are past the security guards, the metal detectors, and the two pillars—once you are standing on the marble floor of the mausoleumlike lobby, it seems certain that the embalmed corpse of Sabino must be on display nearby. But not even his house is there. Franco, who, like Sabino, understood the importance of symbols, had it destroyed. One of the workers on the demolition seemed to have had nationalist leanings, and he saved a balcony railing, which he kept in his own house during decades of silence. The ornate nineteenth-century ironwork piece now rests above the lobby of the party building, an intentional anachronism.

The Sabino Arana Foundation, also based in this building, gives annual awards, like a nation bestowing its Medal of Freedom. In 1997, the recipient was the Tibetan government-in-exile. The PNV remembers exile. The 1998 recipient was the Saharan Polisario Front, which has been fighting for decades for independence from Morocco.

If the PNV had wanted to improve the museums of Bilbao, the city had another museum, the handsome old Bellas Artes, considered one of the better museums in Spain, which could have been expanded.

But the party leadership had something else in mind. It is what has always been on their minds: nation building. The leadership is well aware that if Euskadi is a nation, it is a tiny nation, and while half the struggle is building the nation, the other half is getting it recognized in the world. The size of their land and their population never seems to moderate Basque ambitions.

TO CALCULATE the exact cost to Euskadi taxpayers of the Bilbao Guggenheim is complicated, or perhaps the leadership wants it to be complicated. The figure usually mentioned is $100 million, which is equal to $56 for each citizen. After paying for the building, the Basques also agreed to pay the Guggenheim for using the Guggenheim name on the building. Furthermore, the Guggenheim Foundation chooses the art for the Bilbao museum. The survey of twentieth-century art that made up the initial exhibit seemed like leftovers from the Guggenheim warehouse. The museum, with the exception of a few Chillida pieces, pays no homage to Basque art. Even Picasso’s great tribute to Basque suffering, Guernica, was not made available for the opening. Officials at the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid, where it hangs, said that it could not be moved because it was too delicate for the journey. But many speculated that the Madrileños feared the Basques would never give the painting back—a fear rooted in the almost self-evident fact that it belongs in a major museum of twentieth-century art only a few miles from Guernica.

And yet the Basque Nationalist Party got what it wanted out of the project. Arzalluz said, “It was expensive, but it was cheap for what we got. When we decided to do it, everyone was against it. But then, it was argued that in the center of Bilbao would be a center of modern art for Europe. Then we saw the light. It is a great thing for the future. More than we ever thought, it is an important building. Everyone recognizes that it is a great building, greater than what is in it.”

Ramón Labayen, who was the Basque government’s minister of culture at the time the project was first proposed, said, “It is a great opening up to the world.” To bring the world to them was seen as far more important to the Basques than promoting themselves to the world. An internationally prestigious American building would do more to make them a nation than a brilliant display of Basque art.

By the time the museum opened in October 1997, Bilbao was a city with a lot of plans. But they rarely included the word culture, except in the phrase industrial culture. “From the beginning we wanted something more than culture. It is an investment,” said Mayor Ortuando. “It will be easier to attract investments because of the Guggenheim.”

This is a city of industry. The hotels here have always offered reduced rates for weekends, because most visitors are Monday-through-Friday business travelers.

The mayor reasoned, “This was an industrial city that was based on iron mines. At the end of the 1980s we started recovering and planning the future. The iron mines were exhausted. Where was the future? How do we use our industrial culture, our traditional work ethic, our human capital? What we could do is use new technology. But this would not be enough. We had a deep harbor, a port with a future, and we could be a service center. We started to develop a postindustrial concept with five points.”

Included in the five-point plan were cleaning up the pollution from the old industry, cleaning the river, separating industry from the center city, expanding the subway system and the airport, building more bridges, enhancing technology and managerial programs in the universities, building new industries . . . After looking at the city plans, the $100 million for the museum does not seem as shocking. But only number five of the city’s five-point plan mentions anything about cultural attractions.

From the PNV point of view, Frank Gehry was the perfect architect for the project. In his sixties, he had become the international architect of the moment based on several major projects in the U.S. Midwest, the American Center in Paris, and an office building in Prague. He also was smitten with Basque country and expressed a personal affection for things Basque, though this was not necessarily reflected in his work. The last thing the PNV wanted was something uniquely Basque. The party wanted something international. The other appealing thing about Gehry was that he had garnered a reputation as a sculptor. His buildings were said to be works of art in themselves. He told the Basques that if he did a museum, he would regard the building itself as more important than the work in it.

That was what the Basques wanted: an important building. What they got was a fanciful-looking structure of curves and tilts, at the base of the mountains, seen at the end of Iparraguirre Street, the long straight avenue of blackening nineteenth-century architecture named to honor the author of “Tree of Guernica.”

The structure has neither the grace nor the originality of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim in New York but seems to almost subconsciously pay homage to that famous softly tapered spiral. As promised, it is more a sculpture than a building. Though interesting to look at from the outside, it offers no new ideas about museum architecture. Inside, the exhibition space may have the boldness but not the fluidity of the Wright building. As in a French airport, you are never exactly sure where to go. It does not have the sense of humor of the Pompidou Center. Nor does it have the traffic. Contrary to the publicity, it did not seem crowded its first year. About 50 percent of the visitors, according to museum figures, were Basques. Basque families, the men in floppy, dark blue berets, wandered through.

But while the foreign press had predicted huge crowds of international tourists, this had never been the stated goal of the PNV, nor is tourism a priority in the plans for the city. The Basque Nationalist Party got what it wanted when the New York Times architecture critic, Herbert Muschamp, called the museum “the most important building yet completed” by Gehry.

The most intriguing side of the Bilbao Guggenheim is the back. Set against a man-made pond, the shiny titanium structures look like a cartoon port, the sort of place where tugboats with big smiles might dock. The traffic speeding over the high, green La Salve Bridge, across the Nervión, appears to be getting swallowed by this titanium monster. Below on the other side is the infamous Cuartel de la Salve, a Guardia Civil station conspicuous for its Spanish flag, a rare sight in Basqueland. Two heavily armed guards stand in front with bulky bulletproof protection, looking unhappy to be there.

When asked for her opinion, a woman who lived in the neighborhood near the Guggenheim said, “I don’t know anything about modern art,” which is what Arzalluz also said. A law professor at Deusto, the university that is also just across the river from the museum, Arzalluz passes by twice a day and looks at the Guggenheim. “I like it more each time,” he said.

Did that mean he did not like it at first?

“No, no, I liked it. But it’s not that I wanted a Gehry building. We are not modern architecture experts.”

Most of the non-nationalist parties were strongly against the project but lacked the votes to stop it. Once it was built, most criticism ended. One of the building’s accomplishments was that it produced newspaper and magazine articles around the world about Basqueland, many of which did not mention terrorism.

But in spite of the publicity, it was still the same old Bilbao, with its ornate, slightly blackened, nineteenth-century architecture, the green Basque mountains showing up surprisingly at the end of streets, and the lentil-brown Nervión River with weirdly colored suds suddenly drifting in the current The government said the river was being cleaned up and it was smelling better. But hotels still lived off of businessmen, not tourists, and continued to give a discount on weekends.

THE GUGGENHEIM is just the most noticeable part of the plan to change Bilbao. As befitting a Bilbao museum, it has an industrial setting on the Nervión. But the container-loading rail yard next door is slated to be moved elsewhere. The city’s problems and the solutions that are being found are very much like those of other nineteenth-century industrial cities, such as Cleveland and Pittsburgh. Except that Clevelanders are not trying to build a country.

One thing about which the PNV has always been extremely clear is the importance of money. Throughout history it was the strength of the Guipúzcoan and Vizcayan economy that guaranteed Basque independence. It is believed that a strong economy will someday win it back again. “Today we have a significant degree of power, and that requires pragmatism,” said Arzalluz. “We are not less pro-independence. It is the same line. But to be a David against Goliath requires intelligence. The economy is the first problem. How to build an economy that works within Europe.”

The death of Franco was an economic disaster for the Basques, though one few regretted. He had used Basque industry as the engine for a false economy, without exports or foreign markets—an economy that was almost completely within Spain and therefore within his control. Basque industry, the oldest in southern Europe, was archaic. This was true of not only steel but shipbuilding and manufacturing. Only a few of the twenty-two paper mills that operated in Tolosa have survived. Eibar on the Guipúzcoa-Vizcaya border has lost its appliance industry.

Like Bilbao, Eibar was built on the nearby iron fields. In the Middle Ages the town made armor, outfitting the soldiers of the Reconquista. Juan San Martin of the Basque Academy of Language descended from an Eibar armor-making family. Eibar is on a river and its manufacturers learned how to harness water power. By the nineteenth century, it had converted its industry to coffeemakers and other appliances. Later came bicycles, which remain a town specialty. But once Franco died and Spain joined the European Economic Community, Eibar products could not compete with those of more efficient French, Italian, and German industry.

The crisis would have come sooner and more gently had Franco not been there. The Basque iron fields that had once exported ore to feed British blast furnaces had become exhausted and could no longer supply even enough for Basque industry. But of even greater consequence, by the late twentieth century it no longer required a huge labor force to produce steel, and a steel mill that operated with a large number of workers could not sell its products at a competitive price in the world market. Until 1975, Vizcayan steel mills were not trying to sell in the world market, but only in Franco’s Spanish market.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Basque industries provided thousands of jobs. In order to carry out his plan of filling Basqueland with non-Basques, Franco had to provide jobs for inmigrantes. But the bloated industries did not die with the Caudillo. In 1975-80, Altos Hornos de Vizcaya was employing 12,000 workers. But for twenty years it had been losing money and the government had been making up the difference. At its height, the steel mill was losing more than $1 billion each year.

Europe made the abandoning of government protection to industry a precondition for Spain’s entry into the European Economic Community. In any event, it would have been impossible to have preserved the system in an open economy. The Spanish market would have been overrun with European goods.

While most so-called rust belt areas have turned to service industries, when the PNV-dominated Basque government took over the management of the Basque economy, it wanted to preserve industry. “The Basque government did not want to lose the industrial spirit of Vizcaya,” said Jon Zabalía, a Vizcayan PNV legislator.

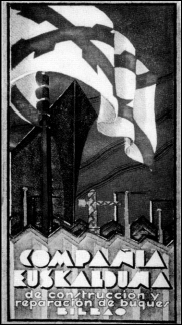

The policy was to identify the industries that could be saved, many of which were owned by PNV families, and to look for new industries. Altos Hornos de Vizcaya was remade into Aceria Compacta de Bizkaia, a company that produces steel by using computers but without blast furnaces. Three hundred and sixty workers now produce 800,000 tons a year—more than Altos Hornos de Vizcaya used to produce with 12,000 workers. Shipbuilding has been reduced but maintained. La Naval, the longtime Spanish government shipbuilder, restructured with 1,800 workers instead of 5,000.

A road runs along one bank of the Nervión and a traveler could look across the river, a particularly dramatic sight against a night sky, and see the fiery red glare of exploding blast furnaces, cranes swinging, tall smokestacks releasing dark clouds. Pío Baroja once wrote of this sight, “The river is one of the most evocative things in Spain. I don’t think there is anything else on the peninsula that gives such an impression of power, of work, and of energy, as this 14 or 15 kilometers of river front.”

Today, it is dark along the Nervión at night. Though there are still a few shipyards and some steelworks, there are no blast furnaces and about 400 industrial buildings have been abandoned. From the death of Franco, for the next fifteen years, Basque jobs were steadily eliminated. Many workers were in their forties and fifties and hard to retrain. They are being permanently supported by Spanish government pensions if they were in the public sector and by the Basque government if they were in private-sector jobs. Thousands from other parts of Spain have gone back to their regions. By 1990, unemployment had reached 26 percent. Since then it has steadily improved. By 1998, it was 20 percent, slightly better than the Spanish average. The per capita income in the Basque provinces is still one of the highest in Spain. But among young people between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five, the ages that Herri Batasuna and ETA are most successful at attracting, unemployment has stayed at 50 percent.

The Basques have remained leaders in banking. In 1988, Banco de Bilbao and Banco de Vizcaya merged into one of Europe’s largest banks. This marked the beginning of a trend in mergers and consolidation of banks all over Spain. Despite these new pan-Iberian giants, the Vizcayan bank created by the 1988 merger, Banco Bilbao Vizcaya, is still the second largest bank in Spain.

Detail from the cover of a 1930 catalogue for the Euskalduna, the now defunct Bilbao shipyard that was founded on the Nervión in 1900 and became a victim of post-Franco economic restructuring. (Untzi Museoa-Maritime Museum, San Sebastian)

Like the nineteenth-century Basques who wanted to use rail links to open up their industry, today’s Basque want to build rail links between Basque cities and Europe. A Basque government-built commuter railroad already runs from Bilbao to Hendaye, linking Vizcaya, Guipúzcoa, and Labourd. It is the first local train to connect France and Spain’s Atlantic coast. Spain, like Russia, had intentionally built its railroad tracks with a nonstandard measurement to protect against invasion by rail.

IN 1867, a group of writers in France, including George Sand, Alexandre Dumas, and Victor Hugo, wrote a guide to Paris in preparation for a world’s fair. Hugo’s introduction to the guide, titled “The Future,” began: “In the 20th century, there will be an extraordinary nation. This nation will be large, but that will not prevent it from being free. It will be illustrious, rich, thoughtful, pacifist and cordial to the rest of humanity. It will have the gentle seriousness of an elder . . . A battle between Italians and Germans, between English and Russians, between Prussians and French, will seem like a battle between Picards and Burgundians would seem to us.”

Only a few years after Hugo wrote these words, the future brought a bitter war with Germany. Two more would follow, leaving Europe all but destroyed. A hundred years after Hugo wrote “The Future,” a broad consensus among European leaders would end borders, end tariffs, and issue a common European passport. The process culminated with the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, which was to change the European Economic Community into the European Union, an entity with one currency and one central bank. The agreement was that all of the members had to ratify the treaty or it would be rejected. But when Danish voters turned it down, Denmark was told that it would be ejected from the community if it did not reverse its decision, which it did by a narrow margin. The voters in other member nations also ratified, in many countries, including France, by the narrowest of margins. Only Spain ratified without consulting its voters, saying that it was unnecessary.

Until recently, one of the central characteristics of Basqueland had been that a border runs through it. The Basques had a border culture. Smugglers and border crossers were folk heroes. Sometimes smugglers would cross the Bidasoa on rafts made of planks. Or a “band of smugglers,” comprising as many as twelve men, would carry goods through the mountains on the darkest nights, undeterred by customs officials who waited in hiding and sometimes shot at them.

SALMÍ DE PALOMA

In the fall, armed men hide in the pine woods by Ibañeta where warriors once waited to pounce on Roland. But they are waiting to shoot the gray-and-white wild pigeons that fly through the pass. The birds are cooked in wine and brandy, which used to be made by monks for the pilgrims. This hunt is at least old enough to be regulated in the 1590 Fuero of Navarra.

The following recipe comes from Julia Perez Subiza of Valcarlos, whose mother-in-law started the Hostal Maitena across from the fronton in Valcarlos in 1920.

Ingredients for one pigeon

1 onion

2 garlic cloves

1 leek

1 carrot

1 sprig of thyme

a little parsley and black pepper

1 glass of brandy

1/2 liter red wine

Cover the bird in flour and sauté it slowly. Chop the vegetables finely and add warm wine to the ingredients, with the exception of the brandy, which is added at the end. Bring the sauce to a boil and then cook gently.

Basques love border stories: In the nineteenth century there was a famous story in Hendaye of French customs officials seizing thirty barrels of wine, but when they triumphantly brought them back to Hendaye, they discovered nothing but water in the barrels. It had been a decoy. In a twentieth-century story, a man crossed the Behobie Bridge over the Bidasoa from Irún, Spain, to Hendaye, France, every day. He would ride his bicycle over the bridge past the Guardia Civil and the gendarmes and would disappear into Hendaye. Later in the day, he would bicycle back with a sack of flour. The Guardia Civil stopped him every day and made him open the sack so they could carefully sift through the flour. But they never found any contraband in it. And they never noticed that he always biked into Hendaye on an old bicycle and rode back to Irún on a new one.

An even greater irritant than the duty on commercial goods was the duty on personal items. Many individual Basques were small-time smugglers, sneaking across items for their own use. In the nineteenth century, well-dressed women would arrive in Hendaye in the morning with flowers in their hair and leave in the evening wearing the latest French bonnet.

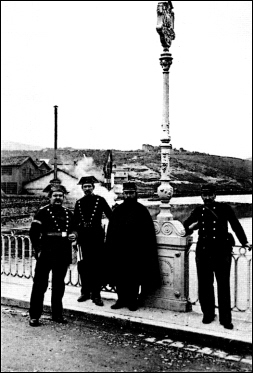

In 1986, Spain joined the European Community, and by the 1990s the border had disappeared. The Pont St. Jacques, or Puente Santiago, where caped gendarmes in cylindrical hats faced caped Guardia Civil in three-cornered patent leather, where young Ramón Labayen and many other Basque prisoners were exchanged, was now largely a truck parking lot A tattered Spanish flag remained. The French one was gone. The shops on the French side, which sold foie gras, chocolates, and champagne, were only open in the summer and had few customers. Without tariffs, French products could be bought for the same price on either side, just as in the days of the Fueros, when the customs began at the Ebro.

French and Spanish customs at Behobie Bridge in the early twentieth century.

What had once been guard stations now were papered over with advertising and a few posters for wanted Basques, torn edges flapping in the breeze. The correct way through, around all the parked trucks, seemed anyone’s guess. Everyone kept more or less to the right of wherever the trucks parked. But if any rules did exist, there were no police or officials of any kind watching anyway.

Behobie offered a similar scene. It was as though the truck drivers, missing their stop with the customs officials, just stopped there anyway.

At the Roncesvalles pass, France becomes Spain at the little stone bridge over the Nive in the village of Arnéguy. Arnéguy is centered on a church and a fronton. A 1920 photograph shows fans from Spain gathered on their side of the bridge to watch a pelote match in the Arnéguy fronton on the other side. There is also a customs house and a shop that sells products from all over France. Until a few years ago, a French flag flew on the little stone bridge, where gendarmes inspected papers and packages. After crossing the bridge and leaving Arnéguy, the traveler climbed along the edge of a mountain to another Basque village, Valcarlos. In Valcarlos was a store selling goods from all over Spain, and a Spanish flag flying, and the Guardia Civil, waiting to inspect papers and packages. Like Arnéguy, Valcarlos has a church and a fronton court. The two villages are much the same except that Arnéguy is at the bottom of a valley and Valcarlos up on the slopes. Both have the same red-trimmed whitewashed architecture. The people of both villages speak Basque.

The customs house in Arnéguy is now closed, the gendarmes and Guardia Civil have left their stations, and the flags are gone. The stores are still there, but without tariffs there is no advantage to buying in one town or the other. A traveler who does not remember from before can drive from Arnéguy, through the pass to the heights of Ibañeta where Roland died, and never know where France has changed into Spain. No one is going to send an army through to fight over the difference anymore.

Jeanine Pereuil said with her customary nostalgia, “You used to hide a little bottle of Pernod in your clothes and nervously smile at the customs official. Now, it’s not any fun at all to go across.”

WHATEVER THE FEELINGS in the rest of Spain, a united Europe is an idea that resonates with the Basques. They are not always happy with the way this new giant Europe is run. To the left, it seems too friendly to corporations and not open to individuals and small business. The dichotomy between large and free, which Hugo promised would not exist, sometimes seems a reality.

But the idea of not having a border through their middle, of Europeans being borderless and tariffless partners, seems to many Basques to be what they call “a natural idea.” “If Europe works, our natural region will be reinforced,” said Daniel Landart. Ramón Labayen said, “The European Union represses artificial barriers.” Asked what was meant by an artificial barrier, he said, “Cultures are not barriers. Borders are barriers.” The borders around Basqueland endure because they are cultural, not political.

When Europeans decolonized Africa, they left it with unnatural borders, lines that did not take into account cultures. This is often stated as the central problem of modern Africa. But they did the same in Europe. The Pyrenees may look like a natural border, but the same people live on both sides.

Arzalluz said, “The concept of a state is changing. They have given up their borders, are giving up their money. We are not fighting for a Basque state but to be a new European state.” A 1998 poll in Spanish Basqueland showed that 88 percent wanted to circumvent Madrid and have direct relations with the European Union.

In the idealized new Europe, economies are merged, citizenship is merged. But those who support the idea deny that countries will be eliminated. There will simply be a new idea of a nation—a nation that maintains its own culture and identity while being economically linked and politically loyal to a larger state. Some 1,800 years ago, the Basques told the Roman Empire that this was what they wanted. Four centuries ago, they told it to Ferdinand of Aragon. They have told it to François Mitterrand and Felipe González and King Juan Carlos.

They watch Europe unfolding and wonder what has happened to their old adversaries. Most of the political leaders endorse the new Europe whether their citizens do or not. Mitterrand, Jacques Chirac, González, and Aznar were all strong backers of this new Europe. The Basques watch the French and Spanish give up their borders and their currency and wonder why it is so easy for them. Why didn’t Mitterrand worry about the “fabric of the nation being torn”? Why does Madrid not worry about losing its sovereignty? And if they do not worry about these things, why do they feel threatened by the Basques?

The Basques are not isolationists. They never wanted to leave Europe. They only wanted to be Basque. Perhaps it is the French and the Spanish, relative newcomers, who will disappear in another 1,000 years. But the Basques will still be there, playing strange sports, speaking a language of ks and xs that no one else understands, naming their houses and facing them toward the eastern sunrise in a land of legends, on steep green mountains by a cobalt sea—still surviving, enduring by the grace of what Juan San Martin called Euskaldun bizi nahia, the will to live like a Basque.