The truth is that the Basque distrusts a stranger much too much to invite someone into his home who doesn’t speak his language.

—LES GUIDES BLEUS PAYS BASQUE FRANÇAIS ET

ESPAGNOL, 1954

THE GAME THE rest of the world knows as jai alai was invented in the French Basque town of St.-Pée-sur-Nivelle. St. Pée, like most of the towns in the area, holds little more than one curving street against a steep-pastured slope. The houses are whitewashed, with either red or green shutters and trim. Originally the whitewash was made of chalk. The traditional dark red color, known in French as rouge Basque, Basque red, was originally made from cattle blood. Espelette, Ascain, and other towns in the valley look almost identical. A fronton court—a single wall with bleachers to the left—is always in the center of town.

While the French were developing tennis, the Basques, as they often did, went in a completely different direction. The French ball was called a pelote, a French word derived from a verb for winding string. These pelotes were made of wool or cotton string wrapped into a ball and covered with leather. The Basques were the first Europeans to use a rubber ball, a discovery from the Americas, and the added bounce of wrapping rubber rather than string—the pelote Basque, as it was originally called—led them to play the ball off walls, a game which became known also as pelote or, in Spanish and English, pelota. A number of configurations of walls as well as a range of racquets, paddles, and barehanded variations began to develop. Jai alai, an Euskera phrase meaning “happy game,” originally referred to a pelota game with an additional long left-hand wall. Then in 1857, a young farm worker in St. Pée named Gantxiki Harotcha, scooping up potatoes into a basket, got the idea of propelling the ball even faster with a long, scoop-shaped basket strapped to one hand. The idea quickly spread throughout the Nivelle Valley and in the twentieth century, throughout the Americas, back to where the rubber ball had begun.

St. Pée seems to be a quiet town. But it hasn’t always been so. During World War II the Basques, working with the French underground, moved British and American fliers and fleeing Jews on the route up the valley from St.-Jean-de-Luz to Sare and across the mountain pass to Spain.

The Gestapo was based in the big house next to the fronton, the pelota court. Jeanine Pereuil, working in her family’s pastry shop across the street, remembers refugees whisked past the gaze of the Germans. The Basques are said to be a secretive people. It is largely a myth—one of many. But in 1943, the Basques of the Nivelle Valley kept secrets very well. Jeanine Pereuil has many stories about the Germans and the refugees. She married a refugee from Paris.

The only change Jeanine made in the shop in her generation was to add a few figurines on a shelf. Before the Basques embraced Christianity with a legendary passion, they had other beliefs, and many of these have survived. Jeanine goes to her shelf and lovingly picks out the small figurine of a joaldun, a man clad in sheepskin with bells on his back. “Can you imagine”, she says, “at my age buying such things. This is my favorite,” she says, picking out a figure from the ezpata dantza, the sword dance performed on the Spanish side especially for the Catholic holiday of Corpus Christi. The dancer is wearing white with a red sash, one leg kicked out straight and high and the arms stretched out palms open.

Born in 1926, Jeanine is the fourth generation to make gâteau Basque and sell it in this shop. Her daughter is the fifth generation. The Pereuils all speak Basque as their first language and make the exact same cake. She is not sure when her great grandfather, Jacques Pereuil, started the shop, but she knows her grandfather, Jacques’s son, was born in the shop in 1871.

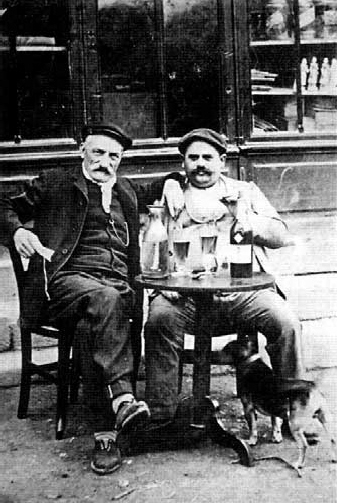

Jacques Pereuil and his son in front of their pastry shop at the turn of the century. (Courtesy of Jeanine Pereuil)

Gâteau Basque, like the Basques themselves, has an uncertain origin. It appears to date from the eighteenth century and may have originally been called bistochak. While today’s gâteau Basque is a cake filled with either cherry jam or pastry cream, the original bistochak was not a gâteau but a bread. The cherry filling predates the cream one. The cake appears to have originated in the valley of the winding Nivelle River, which includes the town of Itxassou, famous for its black cherries, a Basque variety called xapata.

Basques invented their own language and their own shoes, espadrilles. They also created numerous sports including not only pelota but wagon-lifting contests called orgo joko, and sheep fighting known as aharitalka. They developed their own farm tools such as the two-pronged hoe called a laia, their own breed of cow known as the blond cow, their own sheep called the whitehead sheep, and their own breed of pig, which was only recently rescued from extinction.

And so they also have their own black cherry, the xapata from Itxassou, which only bears fruit for a few weeks in June but is so productive during those weeks that a large surplus is saved in the form of preserves. The cherry preserve-filled cakes were sold in the market in Bayonne, a city celebrated for its chocolate makers, who eventually started buying Itxassou black cherries to dip in chocolate.

Today in most of France and Spain a gâteau Basque is cream filled, but the closer to the valley of the Nivelle, the more likely it is to be cherry filled.

Jeanine, whose shop makes nothing besides one kind of bread, the two varieties of gâteau Basque, and a cookie based on the gâteau Basque dough, finds it hard to believe that her specialty originated as cherry bread. Just as the shop’s furniture has never been changed, the recipe has never changed. The Pereuils have always made it as cake, not bread, and, she insists, have always made both the cream and cherry fillings. Cream is overwhelmingly the favorite. The mailman, given a little two-inch cake every morning when he brings the mail, always chooses cream.

Maison Pereuil may not be old enough for the earlier bistochak cherry bread recipe, but the Pereuil cake is not like the modern buttery gâteau Basque either. Jeanine’s tawny, elastic confection is a softer, more floury version of the sugar-and-eggwhite macaroon offered to Louis XIV and his young bride, the Spanish princess María Theresa, on their wedding day, May 8, 1660, in St.-Jean-de-Luz. Ever since, the macaroon has been a specialty of that Basque port at the mouth of the Nivelle.

When asked for the antique recipe for her family’s gâteau Basque, Jeanine Pereuil smiled bashfully and said, “You know, people keep offering me a lot of money for this recipe.”

How much do they offer?

“I don’t know. I’m not going to bargain. I will never give out the recipe. If I sold the recipe, the house would vanish. And this is the house of my father and his father. I am keeping their house. And I hope my daughter will do the same for me.”

Itxassou cherries