Introduction

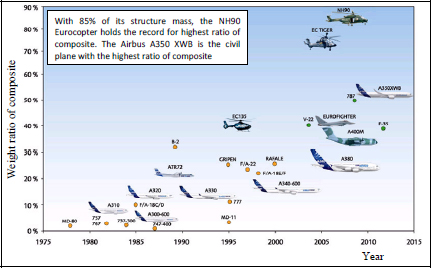

Composite materials are increasingly used within industry, thanks to their high performance to mass ratio. This is, of course, particularly true in aviation and airspace due to the crucial importance of the mass of such structures (Figure I.1). This high performance to mass ratio is due to the use of materials with specific mechanical characteristics such as carbon, glass or Kevlar. This type of material nonetheless presents the major drawback of being brittle, and therefore needs to be used in combination with a less brittle material such as resin. This is the basic concept of composites, which join a brittle resistant material (typically fibers of varying length depending on the application) with a less effective but more resistant matrix (typically resin). Don’t forget that there is then an interface that appears between the two materials which also plays an important role in the behavior of the composite.

Figure I.1. Weight ratio of composite material in aircraft structures from the Airbus group and a few others (http://www.airbus.com/)

The structure of the composite is therefore more complex than a standard homogeneous material such as metal, and requires an entirely new way of designing parts. Composite structure design means designing the structure at the same time as the material; this is the fundamental difference between designing a metallic structure and a composite structure. This composite design also requires classic design iterations on the geometry as well as design iterations on the material itself; these two types of iterations are, of course, inherently linked. In practice, on top of deciding geometry for the structure, the choice of stacking sequence and manufacturing process will have to be taken into account.

The majority of composite materials also present an important anisotropy (meaning its characteristics depend on the direction considered); they are presented in the form of unidirectional fibers, i.e. all facing the same direction. The performance of the composite is, of course, much better in the direction of the fibers, and since in reality a structure is generally under different loadings depending on the direction, a good choice of fiber orientation will make for a bespoke material adapted to real situations. This optimization of the direction of the fibers then allows a mass benefit and therefore a high performance to mass ratio. This benefit will nonetheless require an optimization process in the direction of the fibers to external loadings, which will also depend on the geometry of the structure, which is why the material and structure must be designed together.

Another important point for composite structures is the possibility of obtaining complex forms in one shot, for example, using layer-by-layer production processes along with molds and counter-molds or dry pre-forms. The advantage is that it decreases the mass and complexity of the assembly of the structure by reducing the number of screws or rivets. We can, for instance, cite the tail fin of the Tristar plane (Lockheed-USA) that was composed of 175 elements and 40,000 rivets with a classic construction, and 18 elements and 5,000 rivets with a composite construction [GAY 97]. Once again, this allows mass reductions while decreasing the number of parts and assembly elements, but requires a more complex design process and forces us to integrate the design of the structure and the material.

However, despite the advantages of composites, one of their main drawbacks is the price of the manufacturing process. Examples include the shelf life of the epoxy resins, the prices of laminate ovens (autoclaves), the resin injection devices, shaping using molds and counter-molds, and even the necessity for non-destructive control and assessment to guarantee that the material is healthy. All of these things make the production process more complex and thus increase the price.

Their brittleness under impact is also a negative factor as it leads to structures being oversized thus counteracting the potential mass benefit in order to guarantee their residual strength after impact. This brittleness is also associated with complexity in repairing these impact damages. These repairs can be complex and repair methods are still ill-suited and need to be refined for large-scale structures subject to impact, such as the fuselages of planes like the Boeing 787 or the Airbus A350.

The objective of this lesson is to present the primary sizing principles of composite structures, in particular the ones used in the field of aviation. The objective is to show the sizing of simple composite structures such as plates, and also to provide engineers with the elements required to perform and interpret composite structure calculations made using a finite element code. The complexity of real structures makes it impossible to size these structures by hand, as is presented in this book, but understanding case studies is necessary for the interpretation of results as complex as those obtained by finite elements or even simply from experimental results.

Before beginning this book, it is recommended that readers have prior knowledge of different existing composite materials, of their reinforcements and resins, and of the semi-products used such as pre-pregs and their primary advantages and drawbacks. Indeed, only a few unidirectional composites will be presented in the first chapter, but there are plenty of books out there that have more in-depth presentations in this area [GAY 97, BAT 13, BER 99, CAS 13, DAN 94, DEC 00, SES 04].