As the healthcare system may be unable to provide adequate routine patient care options, the ED becomes overburdened. The lack of bed availability in some areas is indeed critical. The average ED should have one ED bedspace for approximately every 2000 patients of the visits evaluated.1 In some facilities, there is no ability to increase the available treatment area. This leaves maximizing efficiency as the only viable option to evaluate additional patients.

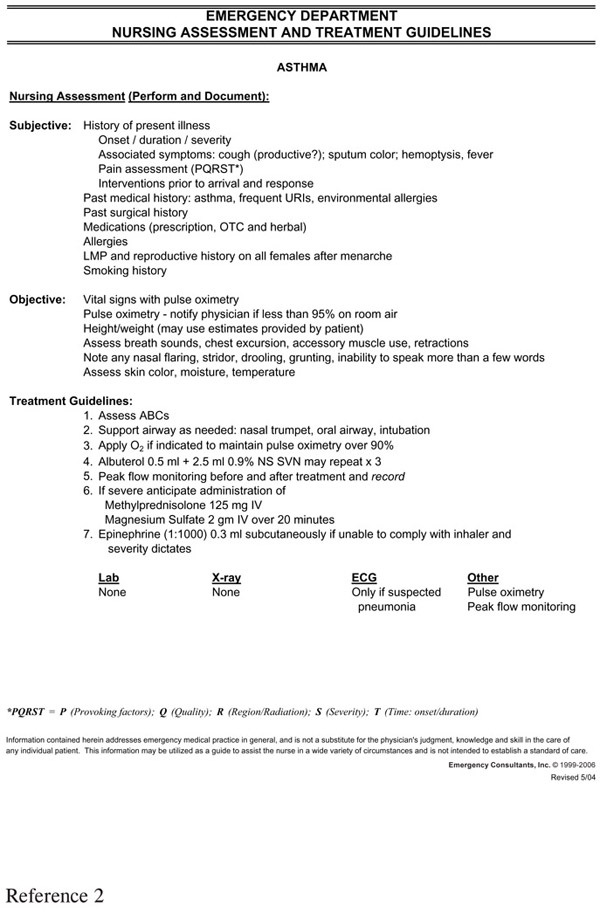

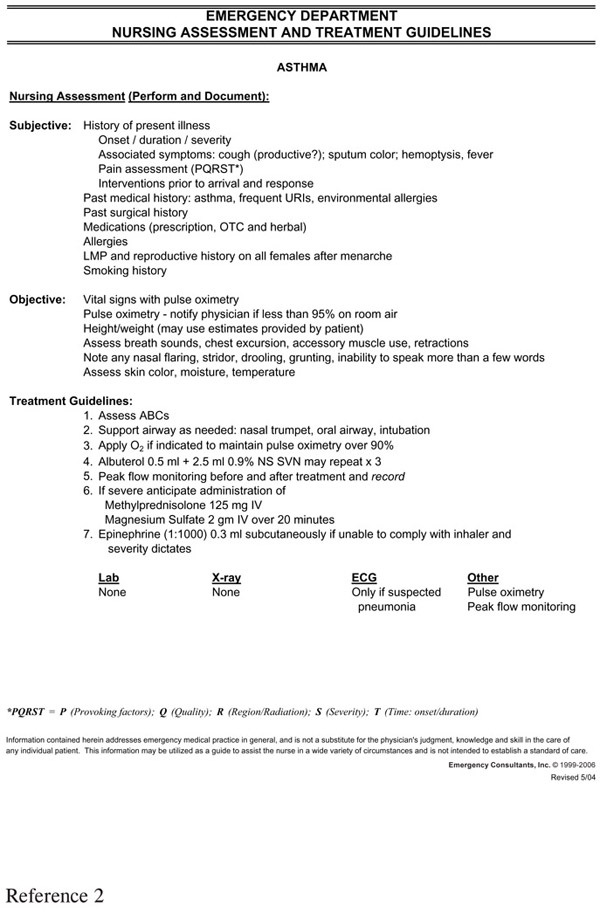

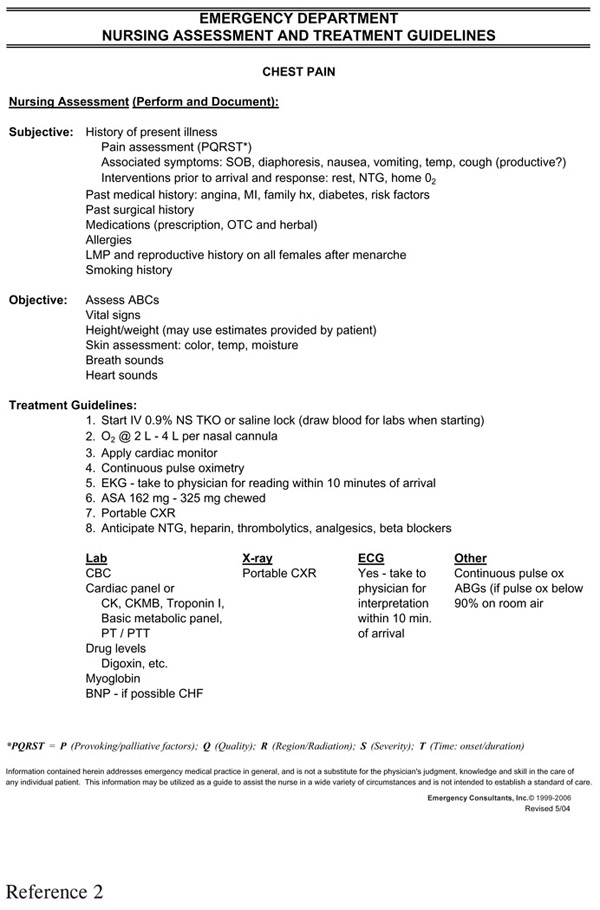

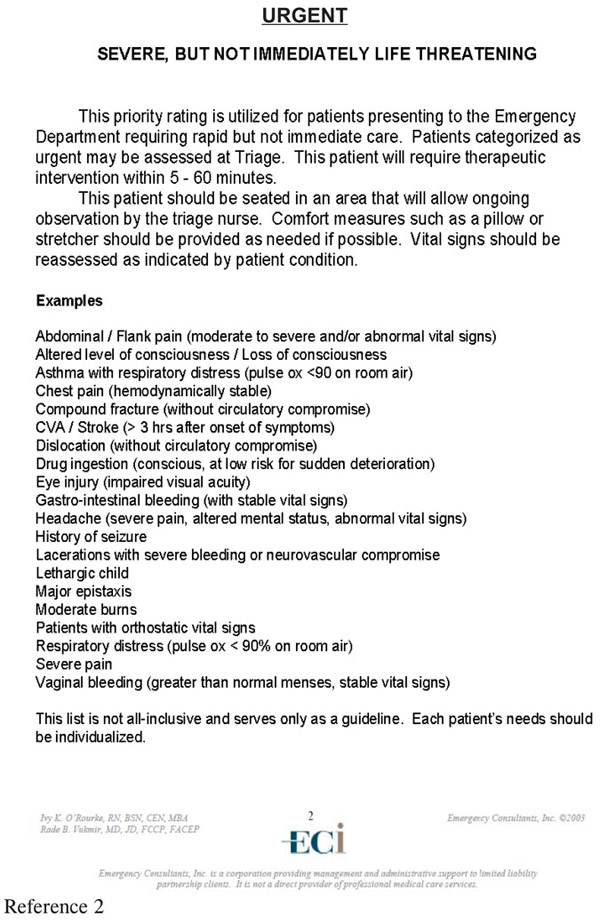

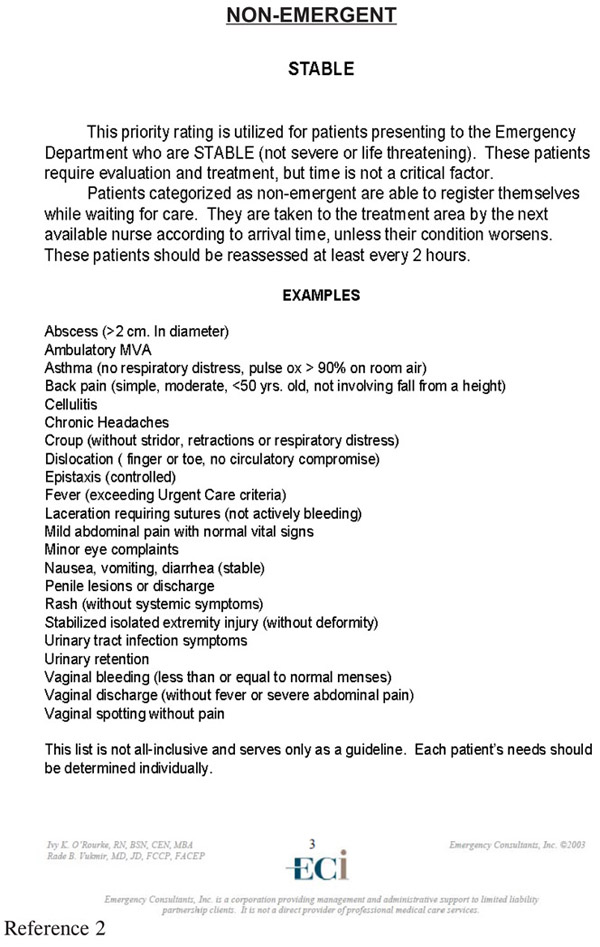

The basis of this approach calls for standardization of patient care protocols. These protocols begin with the ability of triage and bedside nurses to start the test-ordering process at the outset of the care event. Here, we feature the asthma and chest pain nursing assessment protocols (Figures 25 and 26). These protocols focus on the time-consuming parts of the care chain such as urine, pregnancy test, or radiology testing procedures.

Lastly, this same standardization requirement extends to the physicians. They should adopt a panel testing approach to avoid unnecessary individual variation in the testing process, as well to avoid sequential testing or subsequent contingency testing based on earlier testing results that can significantly decrease the efficiency of the department. Likewise, it is prudent to evaluate the patient’s needs for emergent ED versus outpatient referral testing.

This invokes the age-old “art of medicine” argument where somehow the doctor’s decision-making process is irreparably harmed if individual variation is decreased. This clearly is not the case, as many variations in care can be accomplished. No one is compelled to do anything based on a test result. This process is clearly best suited to a high-risk condition such as chest pain where the medicolegal burden to perform “available” testing is well-established. The perception that a test that was readily available to the ED staff that was performed for the patient raises significant responsibility questions and in some cases even suggestion of punitive withholding associated with alleged aggravated negligence.

Figure 25. Nursing Triage Protocols

Figure 26. Chest Pain Protocol

Likewise, early admission decision-making can rapidly improve turnaround time. This approach is also well-adapted to chest pain where the admission decision is made almost literally from the start of the care event. Here, most patients at moderate or high pre-morbid risk warrant admission independent of subsequent lab testing results.

If you were to ask the average ED practitioner—either the physician or nurse—you would be assured that bed boarding is their greatest problem affecting day-to-day operations. There can be a decrease in departmental efficiency of 30 – 50% on an average bed boarding day. The cost estimate of lost revenue per ED bedspace in 2006 averaged $400 –$500 per hour and was only exceeded by the time for operating room space, at $600 –$1000 per hour or, comparably, ICU bedspace at $5000 –$8000 per day.

The “bed restriction” process begins with the lack of physical bedspace assignments, but actually boils down to “no nurses at all” or “no nurses able” to take additional patients at that point in time. As the medical ward processes its budget of wage costs, this “ED hold status” then converts the ED from a potential direct and indirect profit center into a cost center, causing the hospital to lose its new patient evaluation productivity capacity.

As discussed previously, it is crucial that the ward nurse can be incentivized, or at least not disincentivized to both accept new patients as well as expedite the discharge of current patients. Clearly, current programs may have little incentive to admit new or discharge old patients; in fact, they may disincentivize, suggesting that hard work is only rewarded with additional work. Again, one approach offered involves having a separate admission nurse who receives some indirect per-capita financial incentive through flex-time capability where early shift completion can be achieved. This would ensure that more admissions could be processed by this same staff.

Another area of focus is “Resource-Matching.” Remember, in the patients’ minds, all of their health care concerns may be“emergencies.” It is difficult for them to acknowledge that their urgent or even routine visit—that could be evaluated in the office or clinic—is not a true emergency. Certainly, that is not their perception during their visit. Here, the goal is to try to match the provider with the patient care requirements for the patient presenting. The best approach in these circumstances utilizes a well-run minor emergency operation.

The terminology is an integral part of the program’s success. The descriptive terms utilized include fast track or rapid treatment center—implying improved turnaround time. Urgent care center implies less than emergent, but more than routine conditions. Finally, minor emergency center, summarizing acuity of presentation independent of the time factor involved in care.

Another point of distinction applies to operational practice as it relates to Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) billing guidelines.3 The condition precedent is that at least one-third of visits are seen in this setting. The three stated criteria include patients seen: 1) on an urgent basis, 2) without an appointment and 3) for treating emergency medical conditions.

Therefore, the classification system dictates an urgent care center, usually free-standing, typically does not meet the third criteria, relaxing the EMTALA guidelines, but associated with decreased reimbursement as well.

The major distinction, however, is between the Type A facility—the typical 24/7 ED held out as an emergency center and utilizing emergency coding (99281–99285)—and the Type B facility—operating as an integral fast track center without the capability of caring for emergency cases associated with intermediate billing codes (G0380–0384). This compares to an integral minor emergency center that accepts all patients including those with lower acuity emergency conditions utilizing conventional emergency billing codes.

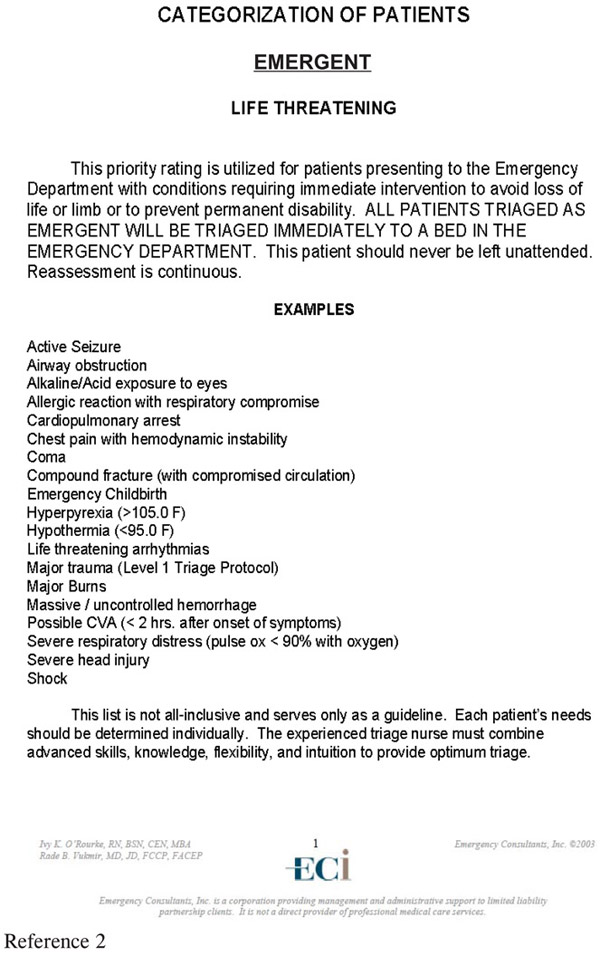

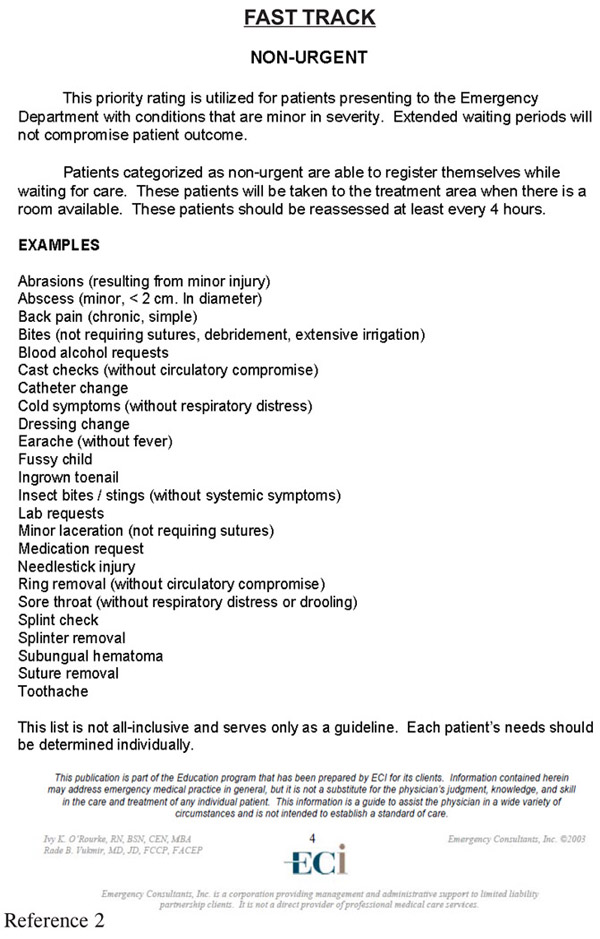

An average of 30%, with a range of 20 – 40% of patients, can be seen in the setting usually by a midlevel provider. Coincidentally, those patients with minor illnesses and accidents appreciate the attentive care that is provided by an enthusiastic midlevel practitioner. If nothing else, this physician extender, physician’s assistant, or nurse practitioner can actually perform medical screening in some states that have by-law provisions to actually assist in redirecting inpatients to the proper care resource (Figure 27).

Figure 27. Triage Protocols

Another approach is to supplement the midlevel practitioner with a primary care physician usually certified in family practice, medicinepediatrics ideally or internal medicine in some cases, who can bridge the gap between urgent care and true emergencies. Their approach to family oriented care often works with the often complex multiple patient evaluation scenario. This leaves the ED physician more suitably matched to more acute critical illness patient encounters.

1. “Benchmarking in Emergency Services.” ACEP Management Course Manual 1994: 7.

2. Emergency Consultants Inc.® Vukmir, R., O’Rourke, I. QualChart Information Systems Patient Management Program. Traverse City, MI. Revision 4.04; 2005 – 2006.

3. http://www.cms.hhs.gov/HospitalOutpatientPPS/downloads/OPPS_Q&A.pdf.