Current analysis of the admission process begins with historical patient processing experience. A 1978 study found that 91% of hospitals maintained an ED unit with a “voluntary” medical staff rotation in two-thirds of sites while 30% were a subcontracted call service.1 This medical staff rotation was exhibited in smaller (<100 bed) hospitals (82%), while larger facilities (41%) used contracted physicians. Resident physicians were used in 30% of cases and 23% contracted staff physicians for coverage.

The proportion of overall admissions accounted for by the ED was 21 – 25% with a range of 16 – 30%. Interestingly, this was a difference based on the corporate ownership status of the facility. The not-for-profit (NFP) hospitals admitted 16 – 30% of patients through the ED on average, 45% in governmental hospitals, and the least 42% in investor-owned hospitals are admitted through the ED.

Now, the overall admission rate through the ED is 15% with a range of 8 – 30% based on age and acuity. The proportion of all hospital admissions that is processed through the ED is now 50 – 75% of the total. A trend toward direct primary and specialty care evaluation of insured patients in the ED, leaving undefined payor classes to receive conventional ED evaluation pathways, can occur in some cases.

The patient admission process has certainly become the paramount issue facing most ED care providers. The primary problem is one of financing of both the inpatient and outpatient encounter. The ever-burgeoning proportion of unfunded care causes progressive deterioration of the payor mix. In some office-based practices, existing patients often report that they are urged to go to the ED if outstanding, unpaid medical balances are present; the same thing sometimes also happens in the cases of new patients if an evaluation fee is lacking for some specialists.

A perhaps too-common scenario becomes the inability of the referral physician to assume responsibility for patient care as workloads become overwhelming.

The solution requires active participation of the administration through a facilitated operational and financial approach to encourage the physicians’ obligation to provide follow-up, on-call care to ED patients encountered—in addition to the EMTALA-mandated requirements.

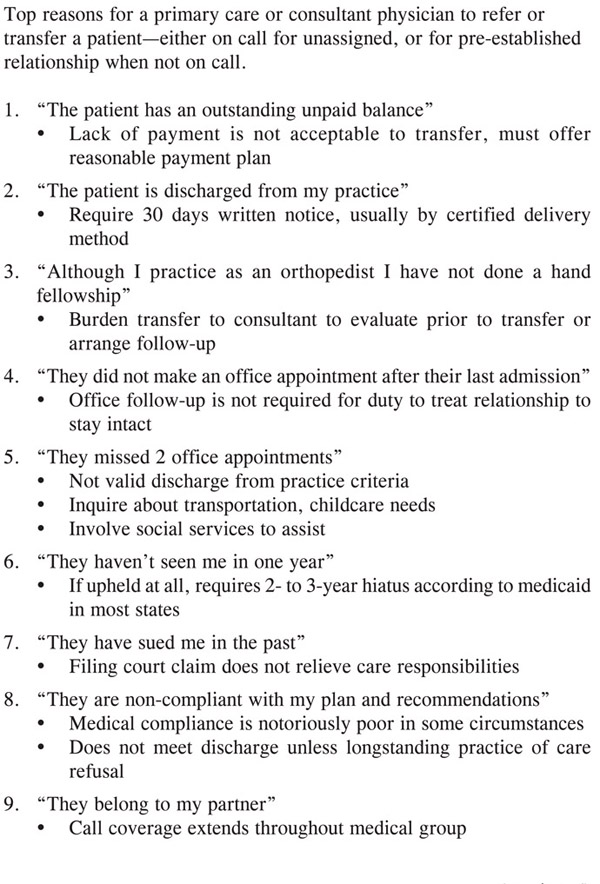

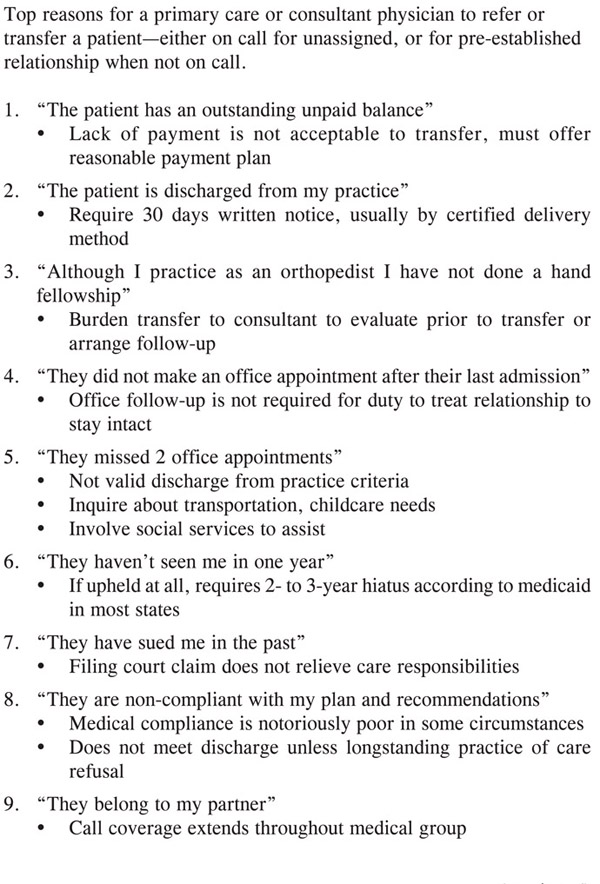

The reasons offered by some on-call physicians for their request for non-involvement center around the premise that the patient could be discharged from the ED. Their rationale is varied and often includes seemingly well-intended reasons for this decision (Figure 28).

First, they might suggest, for instance, that the ED physician is perhaps inexperienced, not knowledgeable enough, or too risk-avoidant to discharge the patient. Certainly, it is counterproductive to trade credentials, but EM is one of the more competitive residencies and its practitioners are usually well-qualified in evidenced-based medicine practice. Unfortunately, when performing their job capably, EM physicians can sometimes increase another practitioner’s workload.

Next, there can be transference to the patient. The referral physician suggests that the patient may be unreliable—they don’t follow up, or they are noncompliant with medications or other recommendations, and they have therefore been “fired” from the practice. Examination of state medical society guidelines finds that this rationale is not endorsed for discharging patients from one’s practice.

Often times a well-intended approach can go awry, such as suggesting that a patient be discharged from the ED so that he can be seen in the office. This approach can be an EMTALA violation if the patient turns out to be “unstable.” Obviously, this condition is usually diagnosed retrospectively, only after an untoward outcome has occurred in a patient who is discharged to “someone’s office” for subsequent care, for which they may not be compliant.

A comprehensive approach is required to handle this multifaceted problem. First, it is necessary to ensure that the same standards exist for credentialing. Generally speaking, all physicians on staff who work in both inpatient and outpatient settings should have the same performance requirements expected and applied. Second, a protocolized and standardized patient care guideline system helps to minimize these individual care discrepancies amongst practitioners.

Figure 28. Rationale to Refer to Another Practice

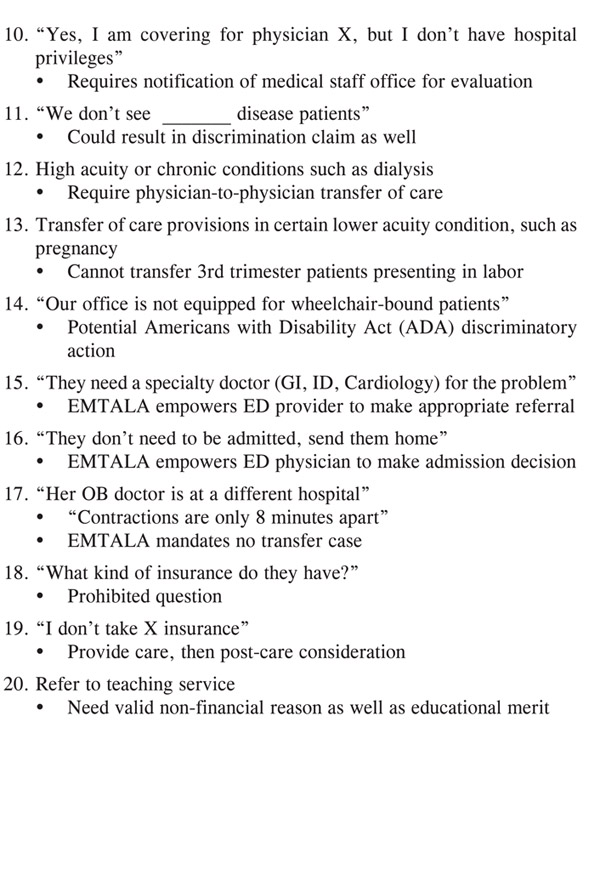

These care events should be made externally reviewable using wellestablished patient care guidelines. Remember, internal peer review can sometimes be flawed due to various subjective issues or bias, and external explicit peer review is often crucial to deciding the proper course for the patient (Figure 29).

Remember, there can be a significant dichotomy in the “continuum” of patient care. The ED physician often strives for maximal sensitivity, attempting to eliminate significant errors of omission. On the contrary, the admitting physician is compelled to stress maximum specificity, attempting to minimize errors of commission. Therefore, the ED physician is compelled to not miss anything, while the admitting physician is forced to not admit any patient unnecessarily—a constant struggle.

Obviously, in the search for the proper balance between sensitivity and specificity or accuracy, the composite endpoint is most desirable. However, erring on the side of caution and admitting more patients than necessary is desirable on an individual basis from the perspective of the social good. However, on a macroeconomic basis, the medical system is potentially at a breakpoint in some areas and the additional cost of inappropriate admissions is difficult to tolerate.

Another slowdown to the admission process is the “One More Test” approach. Here, a perhaps “too complete” workup is suggested by one practitioner to help to refine the diagnosis or to solicit another physician or service to admit the patient instead. Here, an effective approach is to the make the admissions assignment to a primary service, while additional testing can be done during the admission to refine the diagnostic and treatment plan. It usually does not change the admission physician; and it usually does not change the patient’s course in the subsequent care of the admission physician.

Occasionally, this scenario ends with a disagreement where the PCP wants the patient to be discharged from the ED without performing a medical evaluation. This forces the ED physician to take the majority, if not all, of the medicolegal responsibility for the patient discharge.

The EMTALA statute is definitive on this point, stating that the ED physician has the final word on the admission decision. However, if it is invoked too often, even in the patient’s best interest, the ED physician can be suggested to be non-collegial.

Figure 29. ACS-Admission Guidlelines Telemetry Care

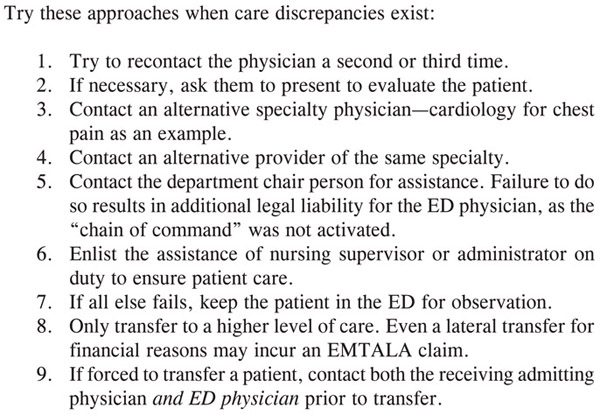

To avoid conflict, the ED physician should first reevaluate their own position to ensure its correctness (Figure 30). Then, it is proper to ask the PCP to evaluate the patient in person, since they often have more longitudinal knowledge of the patient history and condition. In the most extreme cases, there is a medicolegal requirement that the physician activate the administrative chain of command involving the department chair, as well as the administrator on duty or nursing supervisor who can also be helpful. The utmost care is required to not expose the patient or family to the difference in care plans between health care professionals. When in doubt, approach another service or facility to admit a patient or utilize a prolonged ED observation course if no other options are available to the physician.

Figure 30. Steps in Conflict Avoidance

1. Kessler, M.S., Wilson, K.C. “Emergency department key factor in hospital admissions.” Journal of the American Hospital Association 1978; 52(24): 87, 90, 92 passim.

2. Emergency Consultants Inc.© Vukmir, R., O’Rourke, I. QualChart Information Systems Patient Management Program. Traverse City, MI. Revision 4.04; 2005 – 2006.

3. Braunwald, E., Mark, D.B., Jones, R.H., et al. “Unstable Angina: Diagnosis and Management.” Clinical Practice Guideline No. 10. AHCPR Publication No. 94-0602; May 1994.