Another potential pinch-point in the admission process is the referral of the patient from primary care to the specialist—or from the specialist to the sub-specialist—for further evaluation. Here, primary care may refer to cardiology for chest pain, to neurology for a transient isthemic attack (TIA), or an orthopedist might refer a hand injury to a hand specialist. This is often associated with further delay in patient processing as additional testing is often requested at this point as well by the specialist physician. Often it seems the testing is directed to refine the diagnosis and that would preclude admission to that service or compel admission to another service.

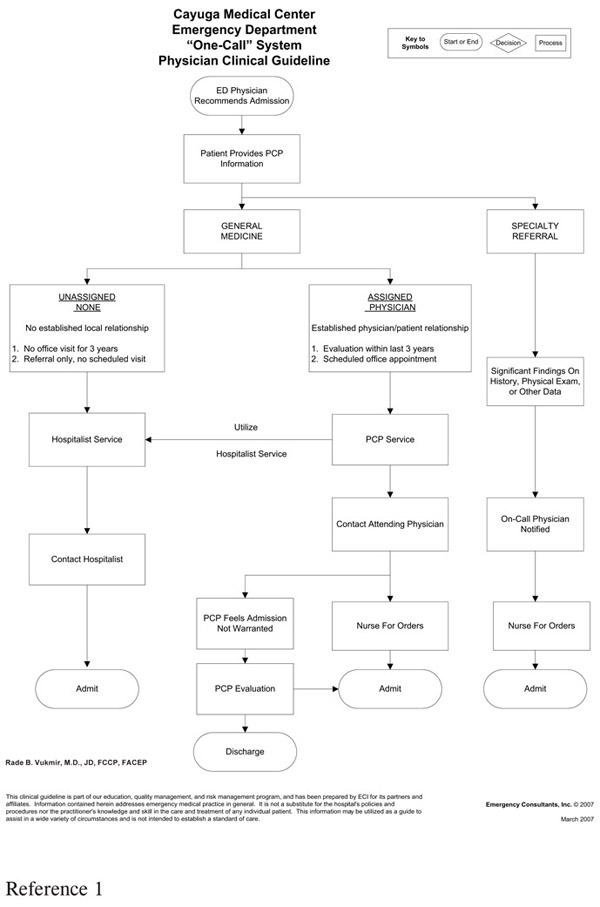

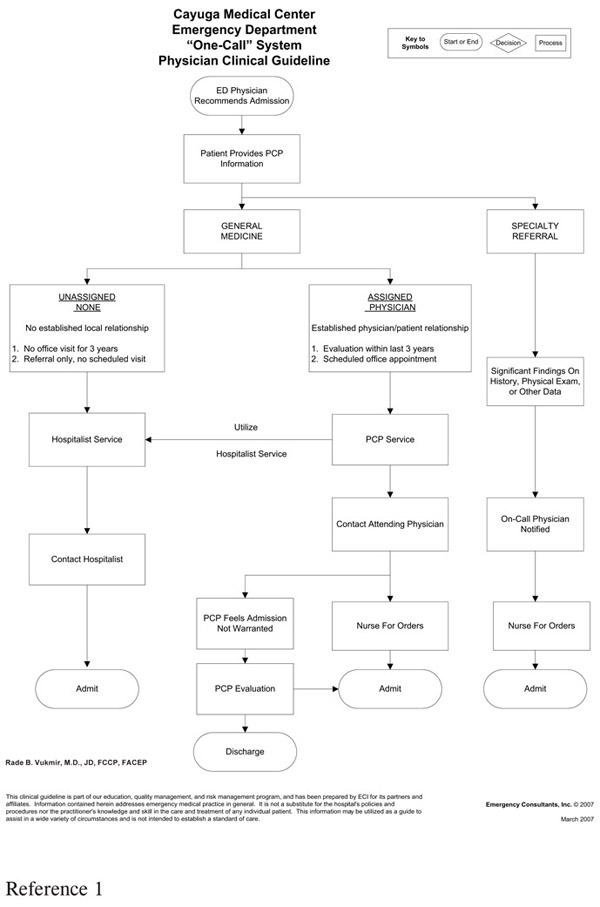

A potential remedy to this difficulty is built around a “One-Call Admission System” process. First, the primary care physician is contacted for evaluation and may then required to notify the consultant himself rather than to enlist the ED staff to perform this task (Figure 31). Secondly, the availability of advanced testing in the ED often encourages over-utilization in this setting to arrive at the proper diagnosis. Here, it is important to recognize the proper disposition – diagnosis dichotomy, with the ED physician most responsible for the former contribution, and the admitting physician the latter. It is clearly desirable that the patients are transferred to the floor to avoid further diagnostic testing. Then only significant positive testing results need to be referred to the ED physician for intervention after the patient is admitted.

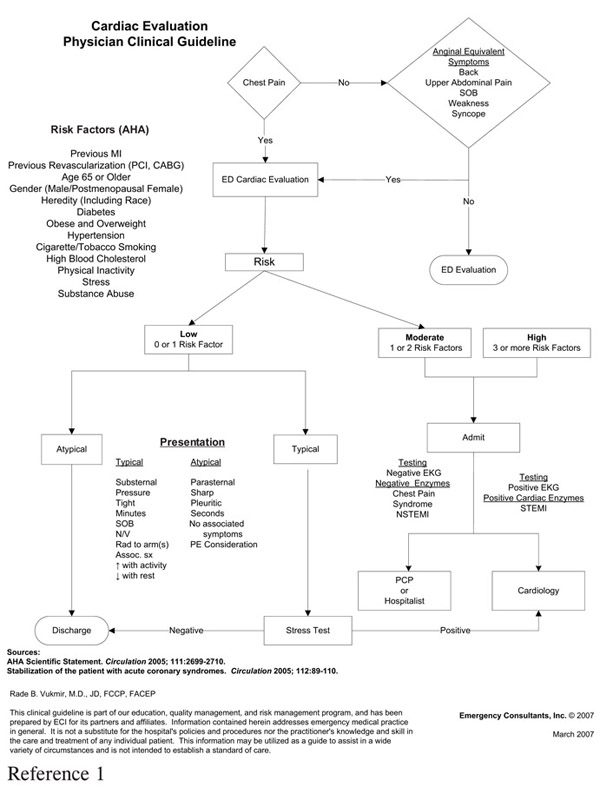

The lack of specialty or sub-specialty availability has become an enormous conundrum in the world of emergency medicine. There are specific “Pay for Call” programs that have become firmly established in specific geographic regions and healthcare markets. Clearly, there is a desire to link risk and rewards of medical practice. This approach stresses the financial rewards over the intangible benefits of medical practice and in some regions appears to involve more specialty than primary care. Call systems where physicians are compensated for onsite evaluation and not the time period of coverage, and clinical protocols such as that for chest pain or other medical conditions may help as well (Figure 32).

Figure 31. “One-Call Admission” Process

Foremost, there is a moral obligation to provide call by the physician who derives a benefit from their hospital association. Simply put, if the hospital offers a service line, it must provide a reasonable call system and if the physician has hospital staff privileges, then they are somewhat obliged to provide on-call coverage. If there is no other recourse than to pay physicians to take call then the “employee model” is a desirable alternative. Here, the economic benefits of the employed physician far outnumber those associated with the “Pay for Call” approach. The employed physician is compelled to evaluate all patients referred without being selective. Unfortunately, in some “Pay for Call” programs, there is an opportunity to achieve the benefits of getting call pay, but not actually having to evaluate any patients during the call period. These programs perform better on a per capita basis where compensation is paid per onsite evaluation or admission rather than for phone consults alone.

There is another novel approach where the specialist now refers to the super-specialist. The most commonly encountered scenario would likely be an orthopedic or plastic surgery specialist who previously would have taken a hand injury, but now passes on a complicated hand injury, mainly because they did not complete a hand fellowship.

The question is a simplistic one — Is that patient better off in the hands of a specialist or the ED generalist for a complicated injury? Obviously, it is the former; even though the specific fellowship training was not done, they are still a specialist compelled by their own specialty board to handle that sort of problem, at least in general terms. The optimum approach for the patient is for the specialist to present and evaluate the case for potential referral to the sub-specialist physician. They then can assign and make transfer arrangements if warranted if there is any uncertainty on the ED physician’s part concerning the care offered.

Often the consultant will ask that a complicated patient be admitted to the primary care physician, even with a specialty problem. The most common scenario is admitting a patient with a surgical or orthopedic problem who may not require imminent surgery due to a multiplicity of medical problems.

Figure 32. Chest Pain Admission Protocol

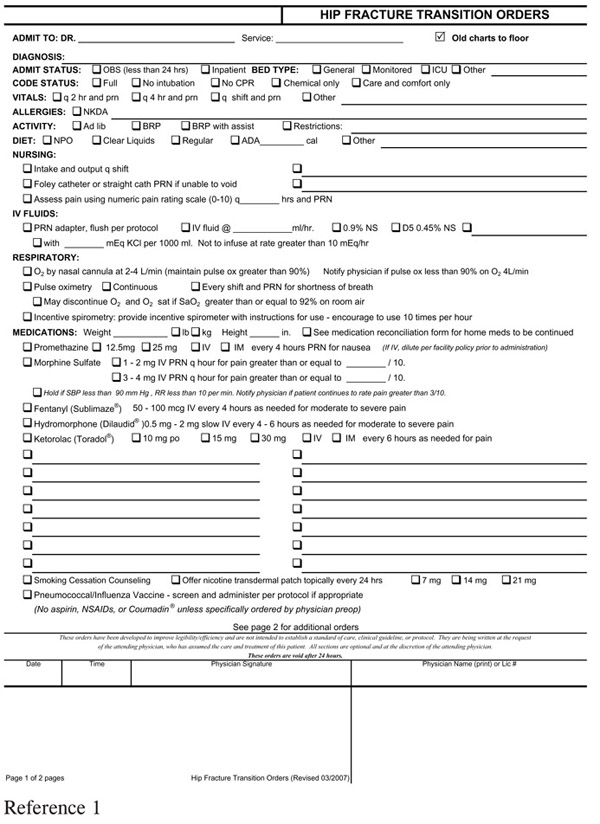

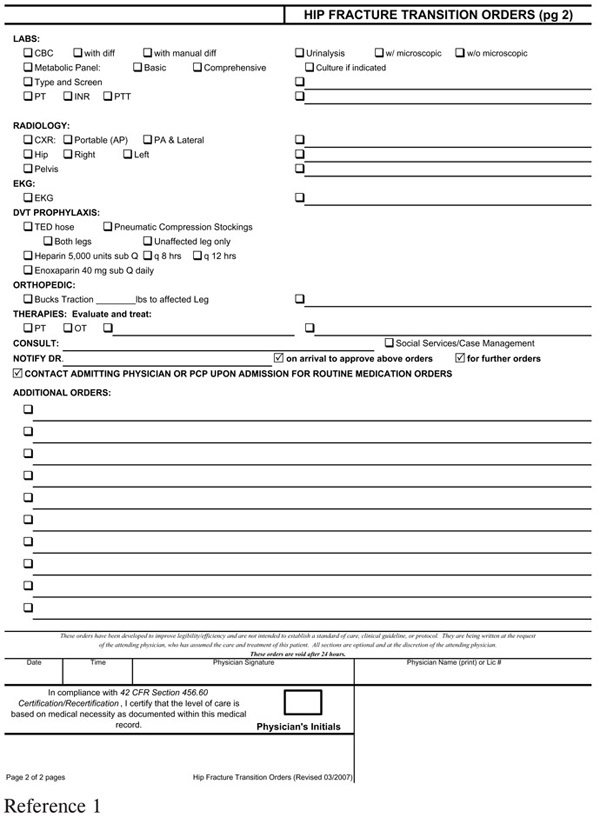

This process can be avoided with clear admission guidelines for specialty disease entities, such as hip fractures (Figure 33). If the admission to primary care is desired, the specialist should make contact for this consultation as well.

Figure 33. Hip Fracture Protocol

Another dilemma is the potential for call transfer within the on-call group itself. This scenario manifests itself when a call physician is unable to assume care responsibility for a variety of reasons. These reasons include situations in which one partner might be on vacation, the group might be short-staffed, or the person on call has no privileges at that institution since they usually cover one another, or they are the only practitioner in the office.

An unofficial comment has existed to deal with this issue—the socalled “three specialist rule.” Actually not endorsed by a statutory mandate, it has some grassroots support in the medical consultation community. This suggestion is that if there are three practicing physicians of a particular specialty, then a comprehensive 365/24/7 call system is feasible for the participants.

These recommendations take the variability out of the physician oncall system for the benefit of the patient and nursing staff.

1. Emergency Consultants Inc.© Vukmir, R., O’Rourke, I. QualChart Information Systems Patient Management Program. Traverse City, MI. Revision 4.04; 2005 – 2006.