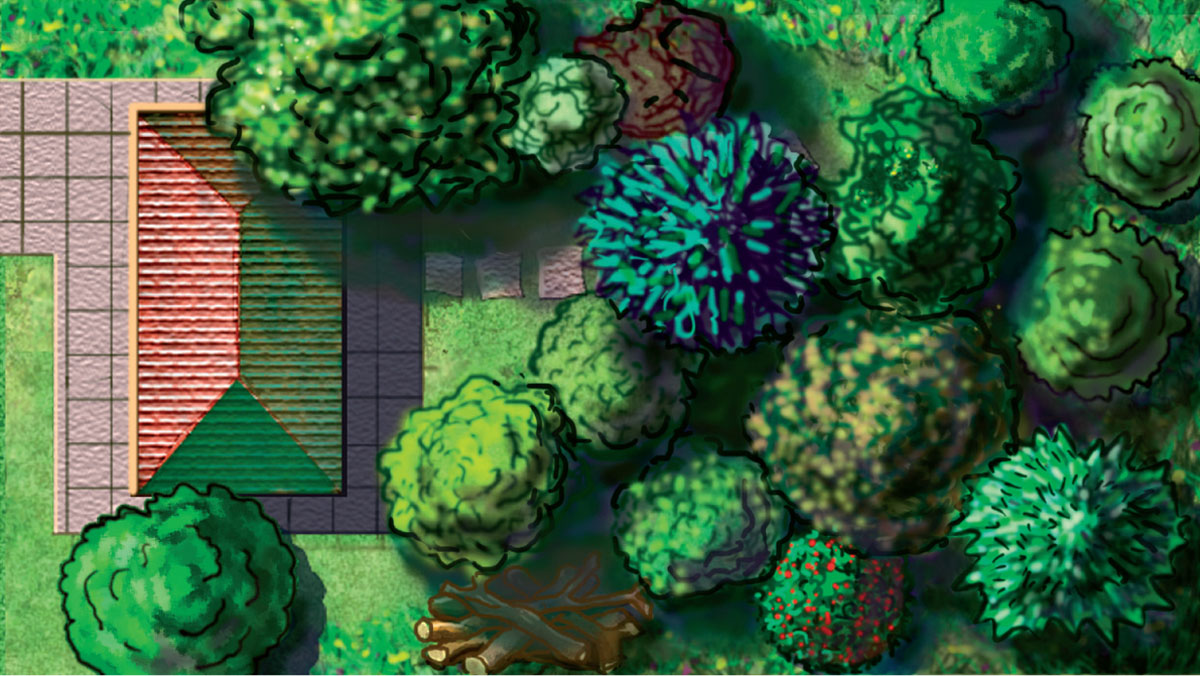

All of these gardens will host wildlife, even if the gardener never intended it.

Myth busting

Ever since gardening for wildlife has seeped into mainstream gardening, a number of ideas have become rather entrenched that are either slightly off the mark or just plain wrong. I believe addressing them is vital and think you may find the truth quite eye-opening.

Myth 1: Wildlife gardens are great for wildlife; other gardens aren’t

On the surface this myth seems to make perfect sense. Mr Smith at number 32 does nothing in his garden to help wildlife, and so his garden must be a desert for wild species. Mrs Jones at number 34, meanwhile, goes to huge efforts to help wildlife, and so her garden must be teeming with life. Surely? It would be terribly unfair if that wasn’t the case.

The truth is that some of the gardens where nothing is purposely done to benefit it can actually be rather good for wildlife. Let me use the street where I used to live as an example. I gardened avidly for wildlife (no surprise there), but my garden was bounded by seven others in which no one else did likewise. They didn’t even feed the birds. I had plenty of wildlife visiting my garden, and yet it visited theirs, too, and not just because ‘my’ wildlife decided to pop over the fence sometimes.

One of my neighbours never went into his garden, or rather ‘jungle’. The trees were 40-foot high, and I couldn’t even see his house. He didn’t garden for wildlife or indeed garden for anything, but there was a fox den in his garden, which I didn’t have, and there were Goldcrests, Chiffchaffs and Willow Warblers far more often than in mine.

Four of my other neighbours had lawns where kids and Scottie dogs played. My garden had no lawn whatsoever. Blackbirds visited their gardens as often as they did mine. On one occasion, I even saw a Red-legged Partridge and a group of Mallards on a neighbour’s lawn, both of which remained dream visitors for me.

In fact, if you are to visit any garden – that’s any garden, anywhere – you’ll find wildlife in it. Whether it’s a pretty, functional, urban or rooftop garden, home to some creature or other. Even gardens that have been paved and decked and sprayed to oblivion still support wildlife of some sort. Not a lot, but a bit.

Why is this important? Well, it reminds us that just because we might call a garden a ‘wildlife garden’ doesn’t automatically make it great for wildlife.

The reality is every garden has wildlife in it; your challenge is to improve it, to make it even better for wildlife.

All of these gardens will host wildlife, even if the gardener never intended it.

Myth 2: Wildlife gardening is something you do in only part of your garden

A garden fulfils many functions for us, and quite right too. Maybe you want to grow some vegetables. Perhaps a lawn is essential because you have a budding David Beckham in the household. For some it is a canvas to be painted with flowers.

If you were to analyse a garden, you might deduce that it has areas that are purely functional, such as paths and clothes lines: let’s call those the function zone. Then there are parts where you enjoy yourself (the leisure zone), places where you grow things to eat (the production zone), and areas that you want to be beautiful (the aesthetic zone). Once all those bits are allocated around the garden, wildlife gets whatever is left over, right?

Well, you can play it that way if you want to, but once again wildlife doesn’t seem to have read the rulebook. It strays cheekily out of the area that was designated for it, and you end up with Blackbirds on the lawn, butterflies in the borders, caterpillars in the cabbage patch and snails everywhere you don’t want them.

So what am I saying? That we should just turn the whole garden over to wildlife? Well no, and yes! Gardening for wildlife is not a case of abandoning all the other things you need a garden to be, not a bit of it. But we’re clever creatures: we can squeeze multiple uses into one area if we try.

How refreshing to be able to dine al fresco within touching distance of wildlife rather than on a large sterile patio.

You may want to keep your washing line away from your bird feeders, to avoid little accidents, but it and meadow butterflies can happily coexist on the lawn.

You want a shed? Great, its primary function is for storage, but with a sedum roof and a nest box nailed to the back, it’s doing its bit for wildlife too. Perhaps you like to entertain guests on your patio? That doesn’t mean that you can’t train wildlife-friendly climbers up a pergola or have pots of nectar-rich plants there.

You don’t have to compromise: you just have to be creative. With a bit of thought we can accommodate ourselves and wildlife throughout the garden at the same time. So prepare yourself for a bombshell: from this point on in the book, you won’t find a single mention of the term ‘wildlife garden’ as it perpetuates the notion it should be a separate part of the garden.

The reality is that gardening for wildlife is about sharing our space with wildlife. Don’t do it anywhere in the garden: do it everywhere!

Myth 3: A garden fit for wildlife must be ‘wild’

Perhaps the most pernicious of all the wildlife-gardening myths is the notion that neat and tidy is out, and shaggy and rambling is the order of the day. You would be forgiven for thinking that unsightly brambles and nettles are compulsory, that your borders should be weed-filled, your lawns straggly and your ponds shaped like a lumpy potato.

There are some excellent formal gardens out there that show why this does not have to be the case. One of my favourites is the Avenue Gardens in Regent’s Park, London. With its strict symmetry, elegant urns and regiments of perfectly clipped evergreen columns, its primary purpose is to look good. It is so masterful in its planting and design and upkeep that I get goosebumps walking through it. But, for all that and despite it being in the centre of London, throughout the summer Avenue Gardens is alive with bees, butterflies and lots of other insects.

And yes, there are some species of animal that do like nettles and brambles, but – as we will see – there are plenty that don’t. As for straight paths or geometric patterns or colour-coordinated planting schemes, wildlife doesn’t mind one jot. I think the key distinction here is between ‘tidy’ meaning ‘orderly’ (which is not a problem for wildlife) and ‘tidy’ meaning ‘sterile’ (which is a no-no).

In the Avenue Gardens in Regent’s Park all manner of butterflies and other insects enjoy the nectar banquet, while we enjoy the glorious design and symmetry.

The reality is that you can be as formal as you like in your garden and still make it a marvellous place for wildlife.

A garden where nature has ‘taken over’ may seem great for wildlife, but it’s not what most gardeners want. Fortunately, a good garden for wildlife doesn’t have to be this way.

Myth 4: There is a blueprint for how to make a perfect garden for wildlife

What should a garden contain if it’s to be as good as it can be for wildlife? Convention would suggest that there is just one way of going about it, one design to follow. Indeed, you might expect to find a diagram later on in this book showing you the bee’s knees of wildlife garden design that you can follow to the letter.

I can save you flicking through because there is no such diagram. Wildlife isn’t a single entity with a single set of needs. Even in gardens, there are thousands of different types of wildlife that you might like to help. And while what’s good for the goose may be good for the gander, it isn’t good for a grasshopper. Different species of wildlife need different things. Very different things.

WILDLIFE GARDENING: TRADITIONAL RECIPE

Ingredients

•Trees

•Pond

•Lawn

•Wildflowers

•Nest box and bird feeders

Method

Take one garden, preferably large.

Hopefully inherit one complete with trees, nice and mature (if not, you’ll need to grow your own).

Make a hole in your mixture and add water.

Let your lawn rise until straggly.

Scatter liberally with wildflowers.

Decorate with a nest box and sprinkle with bird seed.

Hey presto!

To explain this more clearly, here’s a plan of an empty garden, waiting to be made fit for wildlife. There are some fairly mature trees to start you off but, other than that, there’s just bare soil – what a dream to begin with a bare canvas!

Let’s follow the ‘conventional’ wildlife gardening recipe. We add log piles, berry-bearing bushes, a random-shaped pond and a wildflower-strewn meadow. Sure enough, we would soon see some butterflies and bees, Blue Tits and a few dragonflies. And there’s absolutely nothing wrong with this if this is the garden you want. In fact it’s fantastic.

But what if we want to particularly encourage wildlife that lives in water? So we dig a pond that covers almost the entire garden. Moorhens will nest, frogs and newts will breed in profusion, and it will shimmer with dragonflies and damselflies in summer. Perfect…

…for them!

No, hold on, what about if now we’re mad keen on butterflies and bees? So we fill in the pond, take out the trees that were casting so much shade, and stuff the garden with well-chosen flowers rich in nectar. We even have flowers in planters on the patio. There are no more Moorhens, but now the garden is alive with insects.

But what if we’d really prefer woodland wildlife, and would like more nesting birds? A carpet of Bluebells in spring would be nice too, and we’d like to encourage more moths. So we turn the garden into a spinney. After a while, sunlight becomes a rare commodity on the woodland floor and few butterflies visit. On the other hand, at night it is moth heaven (and great for bats), and there are now many more species of breeding bird.

The reality is there is no rigid formula for gardening for wildlife; there are thousands of possibilities that are in their own way brilliant for different sorts of wildlife.

Myth 5: You can attract wildlife to your garden

Oh come on, surely I’m joking now? Am I really saying after all this that there’s actually no way of attracting wildlife to your garden? We might as well pack up and go home!

OK, I admit it, there is a nugget of truth in this myth and you can attract some wildlife to your garden. The scent from your flowerbed will waft to the bees a few gardens down the street; your lush oasis will be a beacon to birds flying over. But the issue here is the word ‘attract’. It can imply that, by gardening for wildlife, you can magically draw in species from far and wide, which you can’t.

Effectively wildlife needs to be within sensory distance to have any chance of being drawn in. No matter how good your gardening is, you are almost wholly reliant on what wildlife is living in your neighbourhood or accidentally stumbles upon your garden as it roves naturally. The skill is in making your garden so welcoming that your existing residents never feel like leaving, while when a creature happens to drop by, it thinks, ‘Blimey, this is good’, and decides to stick around. Your goal is to be the perfect host to the passing traveller and the present inhabitants.

The good news is that, given time, lots of wildlife will pass your way. It’s what creatures are designed to do. Every year, a trillion new ones (give or take a million) are born and head out into the world to house hunt. Probably at this very moment, some animal is wandering across your garden looking for a new home.

If they don’t find what they’re looking for, they’ll soon be gone, and you’ll never know they visited. But if they find somewhere that offers them food, drink and accommodation, they’re likely to be very grateful and stay put.

But lots of wildlife will never pass by. You may create the most wonderful habitats imaginable but if species can’t get to them – maybe they shy away from people or don’t like crossing roads – then your garden will never get visited.

The reality is you’ll do the best job for wildlife if you understand which species are likely to visit your garden, and you give them the best welcome you can when they do.

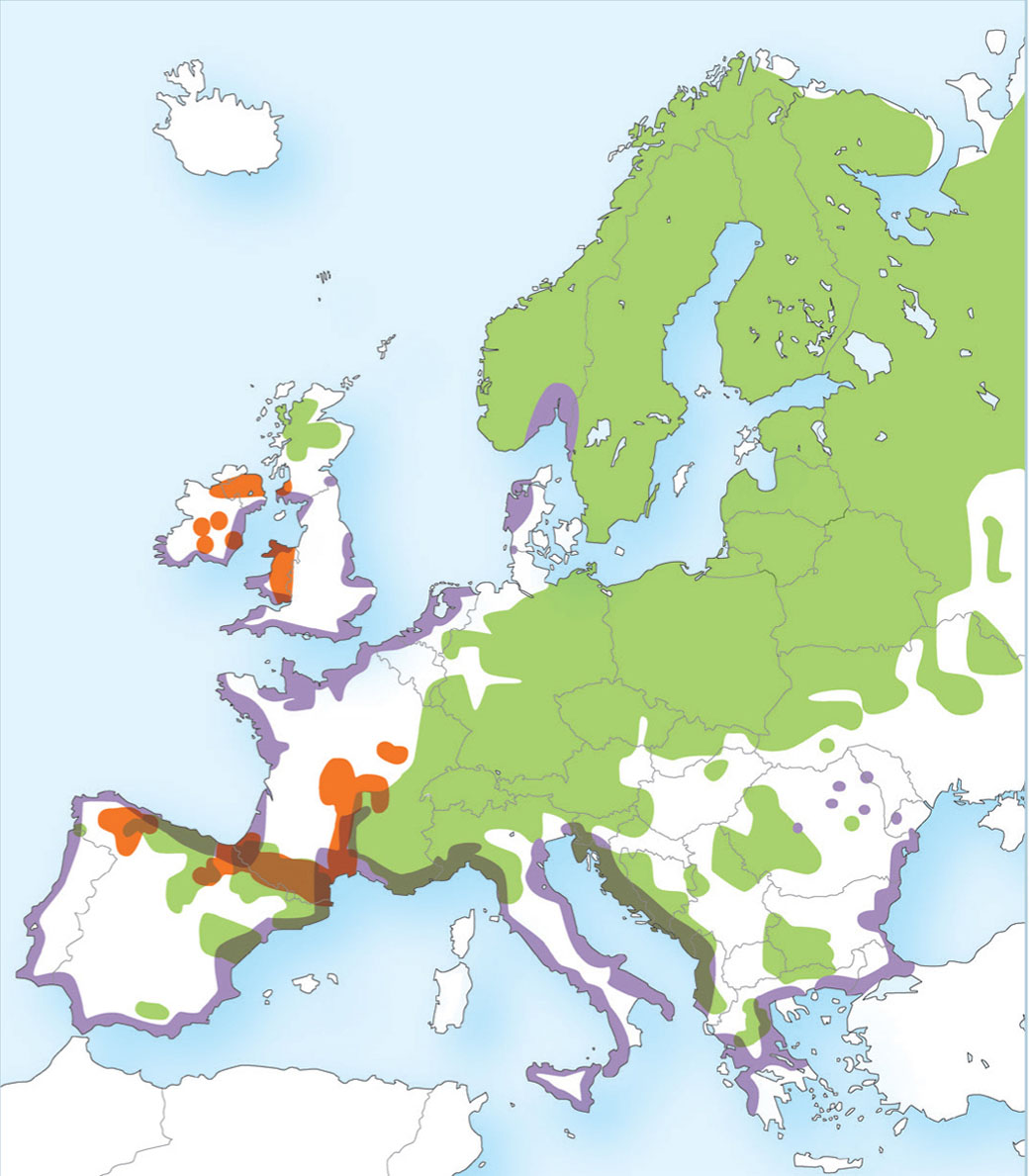

You might be very tempted to try to help Brimstone butterflies but, as they are not found north of Cumbria, there is no point trying if you live in Scotland.

Myth 6: You must grow native plants

This one is quite complex, so bear with me through to its conclusion. It starts with one of the most abiding myths – that if a plant is native, it must be great for local wildlife, but if a plant comes from somewhere else, it won’t be.

On the surface this seems a logical argument. Pop into your local garden centre and it can seem like the United Nations of the plant world, where you can choose blooms from every continent. In contrast, most garden wildlife is ‘home-grown’. Our wild creatures have evolved over millennia here on our shores, where they are adapted to using our native flora and not those recent imports from foreign parts .

The implication is that you must forsake all those exotic plants, which look nice and might grow well in your garden, for native plants that are often not as attractive or suited for cultivation.

But it’s not as simple as it sounds. First, when is something ‘native’? When it is naturally found in a certain country? The problem is that our boundaries are political rather than natural – a nation’s border usually means nothing to wildlife.

Three plants native to the British Isles, but Scots Pine (green) is native only to parts of Highland Scotland; Welsh Poppy (orange) to parts of Wales, South-west Scotland and Ireland; and Yellow Horned Poppy (purple) is wholly coastal. None are likely to be native to where your garden sits.

Take the Scots Pine, so often listed as a ‘native’. However, in the UK it is naturally found only in northern Scotland. If you live in Cornwall, you are some 800km away from its natural range. Conversely, you won’t find the ‘UK native’ Pasqueflower, Hop or Field Rose growing naturally in Scotland – these are all species from south of the border.

There are also rather a lot of very familiar countryside plants, such as the Common Poppy, that you’d swear were native but aren’t. They are what are called archaeophytes, brought to this country by early settlers.

So just because something is called ‘native’ that doesn’t mean it’s what the wildlife in your area is looking for or expecting.

The second problem is that ‘foreign cuisine’ can be really rather tasty, as we all know! Take bird food. Sunflower seeds are clearly adored by many birds. But not only are sunflowers native to the Americas, they have also undergone about 6,000 years of cultivation and then several trips into modern laboratories in order to generate big yielding hybrid cultivars. If you feed peanuts, it’s the same story – they are South American in origin, and are now mass-produced from cultivars.

Also, the seed mixes that farmers are encouraged to grow in field margins to benefit declining farmland birds are a mixture of plants such as Wheat and Rye (which aren’t even known as wild plants), Triticale (a man-made hybrid cereal), and Quinoa (a plant from Lake Titicaca in Peru). And it’s not just seeds: there are plants that are happily visited here in UK for nectar and pollen but which originate in China, South America, Australia...

So, the reality is that plenty of non-native plants are great for wildlife, while many native plants are actually not that good. The Biodiversity in Urban Gardens (BUGS) project provided some scientific proof for this. To quote Ken Thompson’s excellent book on the subject, No Nettles Required, ‘Most wildlife is almost completely indifferent…to whether plants in your garden are native or alien.’

In fact, it seems possible to create a stunning garden full of wildlife using only non-native plants.

But…

Before we start discarding all those native plants, there are some VERY important caveats.

The first is that some native plants are essential for certain wildlife. Some insects, for example, are so picky they will only eat one type of plant and that, of course, is almost always a native one. So if you don’t have buckthorns, Brimstones won’t breed, and if you don’t have bedstraws you won’t have Hummingbird Hawkmoths.

The second is to realise there are plenty of non-native plants that are absolutely rubbish for wildlife.

It is vital too that you never plant or carelessly discard non-native plants that are invasive in our countryside. Those causing the biggest problems are here.

The tightly packed seedhead of Quinoa is an energy-packed treat for many birds, even those that live far from its native Peru.

Although some non-native plants do have wildlife value, there are great reasons to plant natives like this Red Campion.

Another caveat is that we still don’t know the full picture about the relative value of native versus non-native plants. The Royal Horticultural Society’s ‘Plants for Bugs’ project has given us some important indications, but there is still much more research to be done.

But nor should you underestimate the aesthetic appeal of some of our native plants. My beloved Red Campion is a prime example – who needs foreign blooms when you’ve got this stunner?

And, finally, there is still something morally compelling about growing the plants that would naturally be found where you live had someone not built a load of houses there. The Natural History Museum runs a great free website called Plants by Postcode to help you find the right species.

As I promised, the question of native plants versus non-natives is far from straightforward. But that doesn’t mean that growing non-native plants and gardening for wildlife don’t mix well. If you’re careful, they most certainly can.