© Bird Watching/Bauer Media.

How Wildlife Sees Gardens

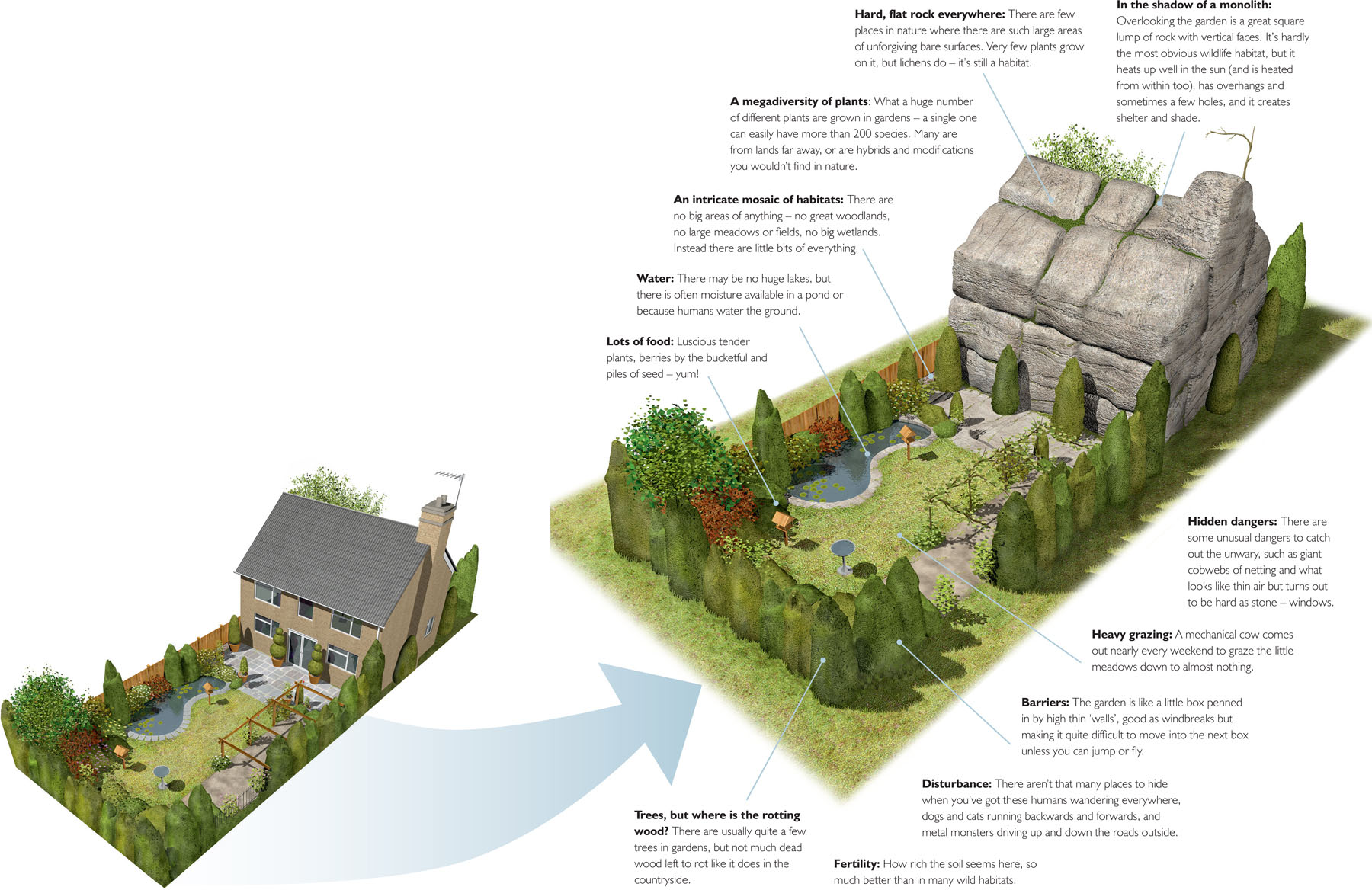

As we’ve seen, when it comes to gardening for wildlife you never start with a blank canvas: every garden has wildlife in it, it is already a ‘habitat’. So it’s worth us delving into what ‘garden habitats’ tend to be all about to get an insight into what wildlife is already using gardens, and why.

Now I don’t think I need to tell you that you don’t get Golden Eagles in gardens. Or Otters. Or hares, Curlews or seals. (Yes, I know that someone out there is going to email me to say that they do, but they are the exception and can rightly feel very smug about it.) Gardens clearly don’t fulfil the home needs of every sort of wildlife.

Take birds, for example. Of the 250 or so regular British and northern European species, only about 30 are widespread in gardens. And butterflies? Of 60 or so species in the British Isles, only about a dozen grace our gardens regularly.

So why is that? Why do gardens satisfy some wildlife but not the rest?

Well, the first thing to understand is that we see our gardens in a very different way to wildlife. We see it for what it means to us: a shed is somewhere to store tools; a lawn is a place for the kids to play; the patio a place to entertain friends; trees, hedges and fences are what offer us privacy.

How wildlife sees a garden is rather different. They are looking to see whether a garden offers them the things they need to survive. Check out this typical garden seen through their eyes...

© Bird Watching/Bauer Media.

On this aerial photograph, I’ve marked in imaginary territories of Blackbirds in pink, and the route a male Brimstone might take through sunnier areas looking for a mate in yellow. If a garden is like a room, clearly some creatures need dozens to fulfill their home needs.

Your garden is not an island

Now I want to zoom out from a single garden and look on a wider scale, with all the gardens and houses and roads laid out like a habitat jigsaw.

There’s a very good ‘gardening for wildlife’ reason for doing this. We are conditioned to concentrate on our own garden because it’s the only one where we have the right to do things and change things. But wildlife doesn’t see the world one garden at a time; it has no idea what’s yours and what isn’t.

From the air you can see that fields aren’t much like gardens – they are too open and uniform. But then woodlands aren’t like gardens either, being too dense and shady.

By looking at gardens in their wider context as nature might see them – houses, roads and all – we can understand how they compare to wild habitats in the countryside and get a feel for which wildlife communities are likely to find a suitable home here in our backyards.

Seen like this, it’s not too hard to imagine why wildlife looking for an estuary or a mountaintop home is very unlikely to pitch down outside our houses. So what habitats are gardens like then? Well, gardens look a little bit like woodland, but the trees tend to be too small and sparse, and the habitat rather too bitty. Gardens also have plenty of grass, but compared to pastures and meadows they’re more shaded and piecemeal. Gardens also have much in common with areas of scrub or newly planted woodlands where there are small trees, open areas and disturbed soil. But gardens are also surrounded by lots of brick and tarmac.

The bottom line is that gardens are really rather weird habitats, not quite like anything else in nature. They are a crazy jumble: bits of this and bits of that. They are also rather a new invention (even though there are now millions of them) that haven’t been around long enough for birds and animals to have evolved to live there and nowhere else. So the species that use gardens are actually successful invaders from a wild habitat.

Sure enough, the woodland element of gardens means that woodland wildlife aplenty has moved in such as Blue Tits and Robins, Speckled Wood butterflies and Foxes. But there is plenty of woodland wildlife that hasn’t (yet) expanded into gardens such as many of the breeding warblers, fritillary butterflies and dozens of moth species.

Of the meadow wildlife, some ants, bumblebees and probing Starlings have successfully set up home in gardens, but creatures that need large areas of uniform grassland, such as grasshoppers and meadow butterflies, are rare while Skylarks are non-existent.

From scrubland comes spiders and shield bugs, but not Whitethroats and Stonechats. And in garden wetlands we find good numbers of amphibians and dragonflies, but few wetland birds or fish.

Wildlife-friendly gardens often resemble a woodland glade, as here in Adrian Bury’s wonderful garden in North Yorkshire, but they are clearly still a distinct habitat in their own right.

Getting your head around hectares

Many species need a certain area of habitat to survive, so in this book you will find I talk a lot about ‘hectares’. One hectare (ha) is simple – it is the area of a square 100 metres by 100 metres. (In imperial measurements, one hectare = 2.47 acres.)

If that doesn’t mean much to you (and area is notoriously difficult to visualise), then the pitch at Wembley Stadium (inside the white lines) is 105 metres x 68 metres which is about three quarters of a hectare. And in tennis courts? Well, about 40 tennis courts make a hectare.

The pitch at Wembley looks pretty big compared to most gardens, but even one pair of small birds, such as Robins, often need a larger area of gardens than this pitch to raise a brood.

Several species of shield bug, such as this Forest Bug Pentatoma rufipes, have made the transition to gardens well, or perhaps they never moved out after the diggers moved in.

Wildlife from ‘wild’ habitats is still moving into gardens as we speak. A hundred years ago, Blackbirds were a woodland species, but some pioneering birds made the crossover and found that gardens were almost perfect for them. Dunnocks did the same from an ancestral mountain home, and now Goldfinches are becoming ever more familiar. Who knows what will arrive next? Maybe Linnets will abandon their need for open spaces and come to see gardens as home; maybe Pine Martens will arrive hunting Grey Squirrels. Who knows?

Gardens it seems are the realm of the adaptable and the brave. The interesting thing is that for some species gardens have become their ideal homes, and some even like it more than where they originally came from.